Since 1952, American employers have hired H‑2B foreign guest workers to fill seasonal or temporary jobs that U.S. workers have not taken. Onerous rules kept participation low until the late 1990s, but as more Americans left these types of temporary jobs, more employers accepted the H‑2B visa’s restrictive requirements as their only chance to find legal workers.

Now the H‑2B program is in crisis. Demand for positions has surged to a level more than twice the visa cap, and many employers fail to fill open positions, which hurts American businesses, consumers, and U.S. workers in other jobs. The process’s complexity and uncertainty caused many others not to apply at all, and in 2020, executive orders banning many H‑2B workers kept the cap unfilled for the first time in several years.

This study explains the complex process that employers must undertake to have a chance to legally employ foreign workers in jobs that unemployed Americans routinely reject. Congress and the administration should reform the H‑2B program to make it easier to hire and retain H‑2B workers. President Biden should immediately rescind the visa restrictions put in place by his predecessor.

Introduction

The H‑2B visa allows foreign workers to work in temporary nonagricultural jobs in the United States “if unemployed persons capable of performing such service or labor cannot be found in this country.”1 While the H‑2B program has existed for nearly seven decades, it has never faced the problems that it does now. Consecutive administrations have added significantly to the program’s costs and complexity, and demand is so far above the cap set by Congress that many businesses are left with unfilled positions, undermining economic growth and incentivizing illegal employment. In December 2020, a presidential proclamation extended a June 2020 ban on many H‑2B workers.2

This policy analysis details the complicated rules that employers must follow to legally employ foreign workers in jobs that unemployed Americans routinely reject. Its findings include:

- The H‑2B program has more than 175 bureaucratically complex rules that inflate labor costs far higher than they would be for most similar U.S. hires.

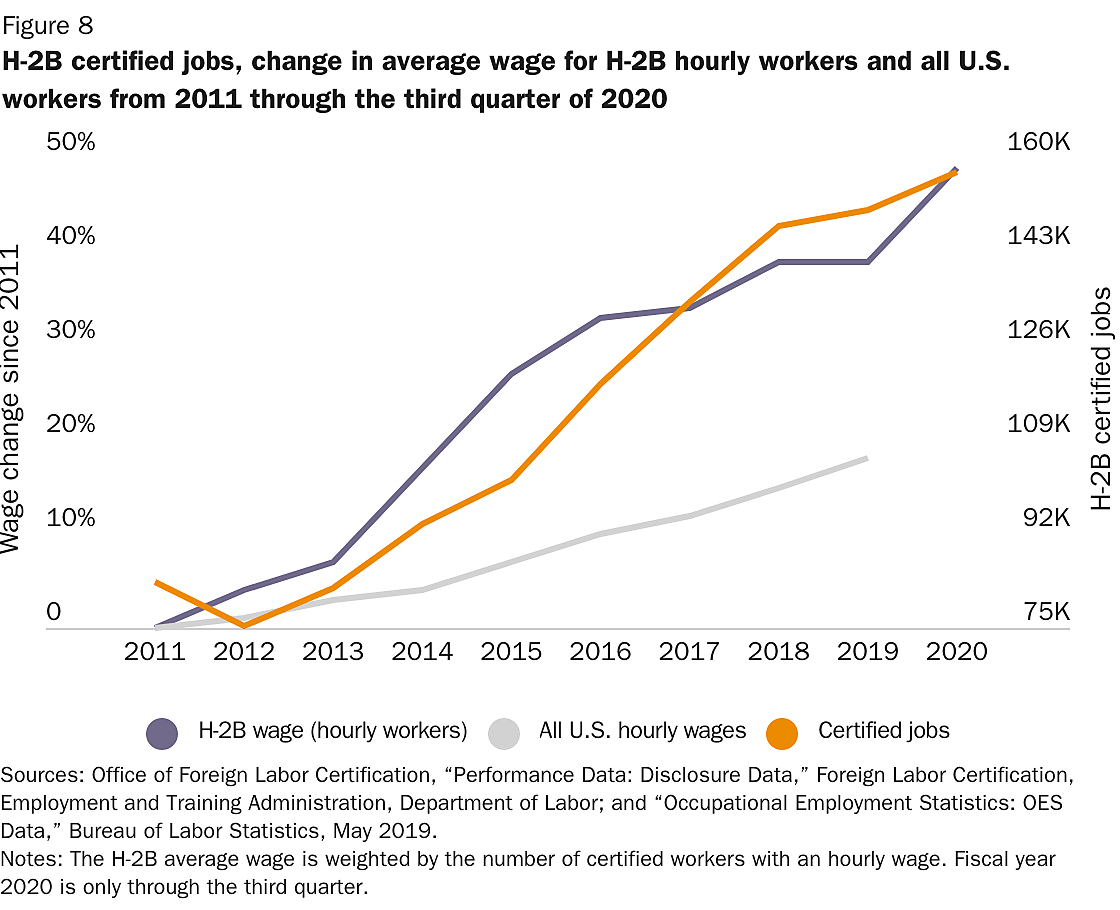

- H‑2B wages have grown at twice the pace of all U.S. wages and exceed every state’s minimum wage by an average of 60 percent.

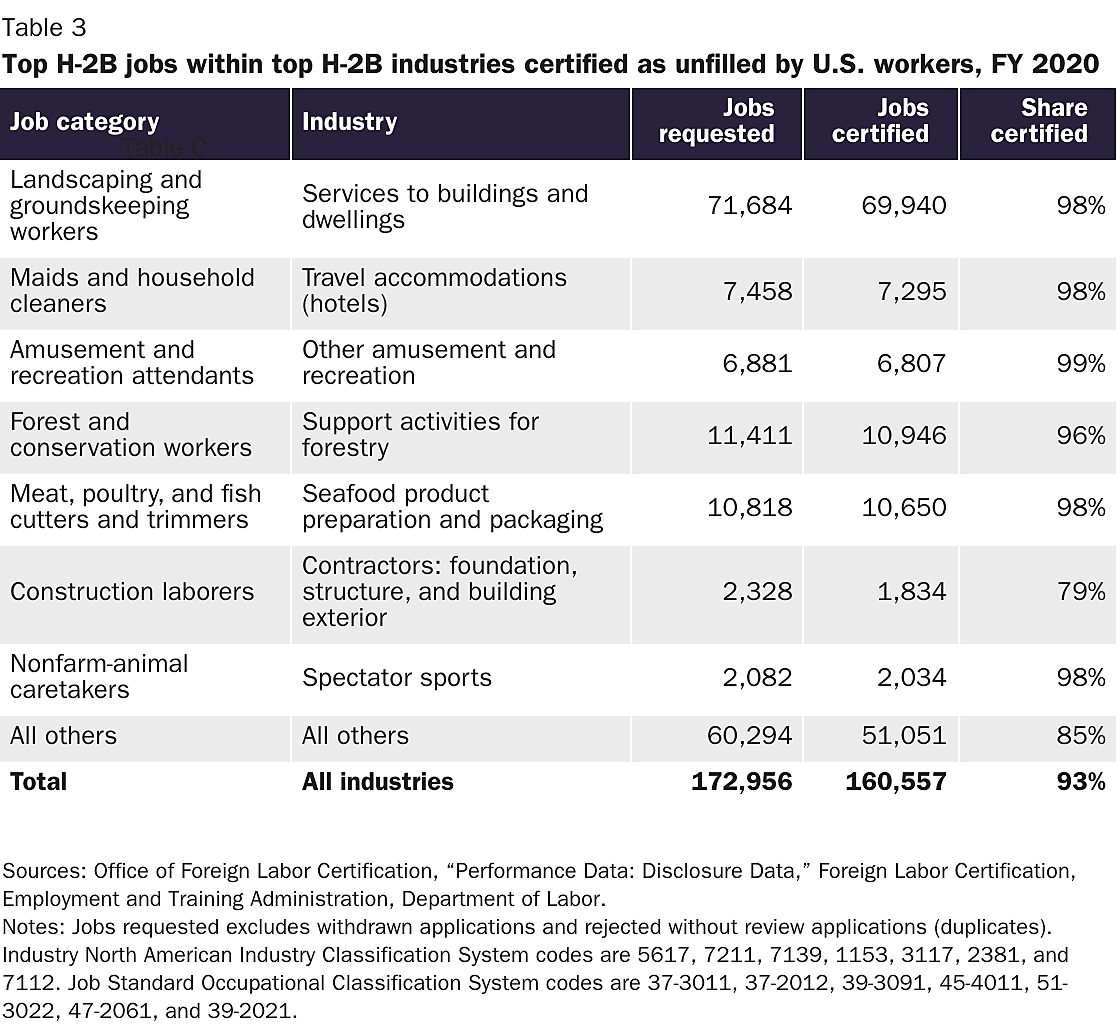

- U.S. workers turned down 93 percent of H‑2B job offers in 2020.

- H‑2B visas have significantly contributed to a 96 percent reduction in apprehensions of Mexicans crossing the border illegally.

Congress and the administration should reform the H‑2B program to make it easier to hire and retain H‑2B workers. The administration should allow employers to recruit U.S. workers who will commit to return to a recurring job year after year. If U.S. workers reject the recurring job, H‑2B workers should be granted visas that are valid for multiple years without subjecting employers to the onerous H‑2B filing process or the H‑2B cap. Ultimately, Congress should uncap the H‑2B program just as it has for the farmers’ H‑2A program because the caps harm both U.S. employers and U.S. workers by keeping seasonal jobs unfilled.

H‑2B Program Rules

An H‑2B visa is a nonimmigrant (temporary) visa for foreign workers who plan to work in temporary nonagricultural jobs in the United States “if unemployed persons capable of performing such service or labor cannot be found in this country.”3 It does not provide for permanent residence or U.S. citizenship. Congress created the H‑2 visa program in 1952 with the intent of creating a process for “alleviating labor shortages as they exist or may develop in certain areas or certain branches of American productive enterprises, particularly in periods of intensified production.”4 In 1986, it relabeled the H‑2 nonagricultural program as “H‑2B,” thus distinguishing it from the H‑2A program for temporary agricultural workers.5

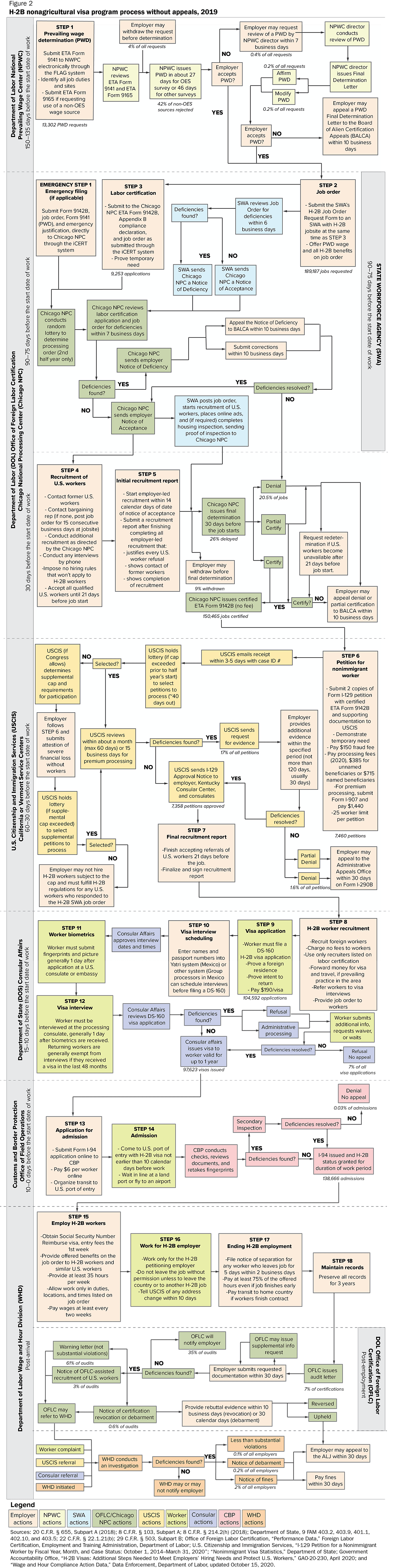

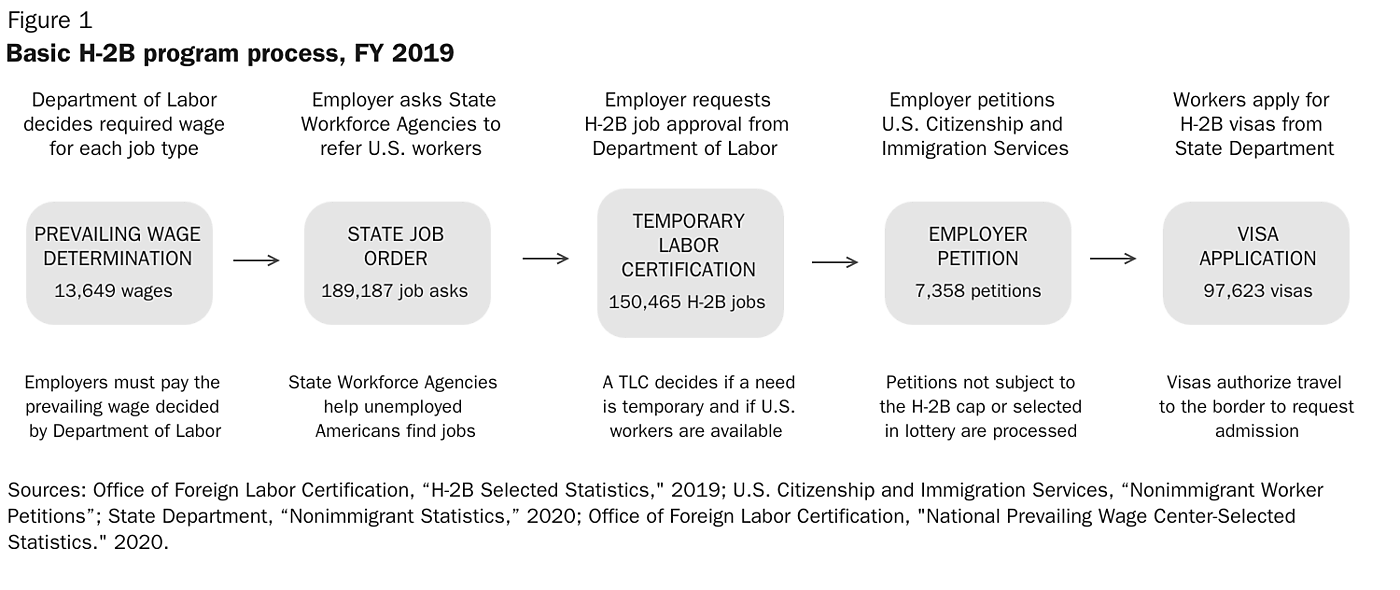

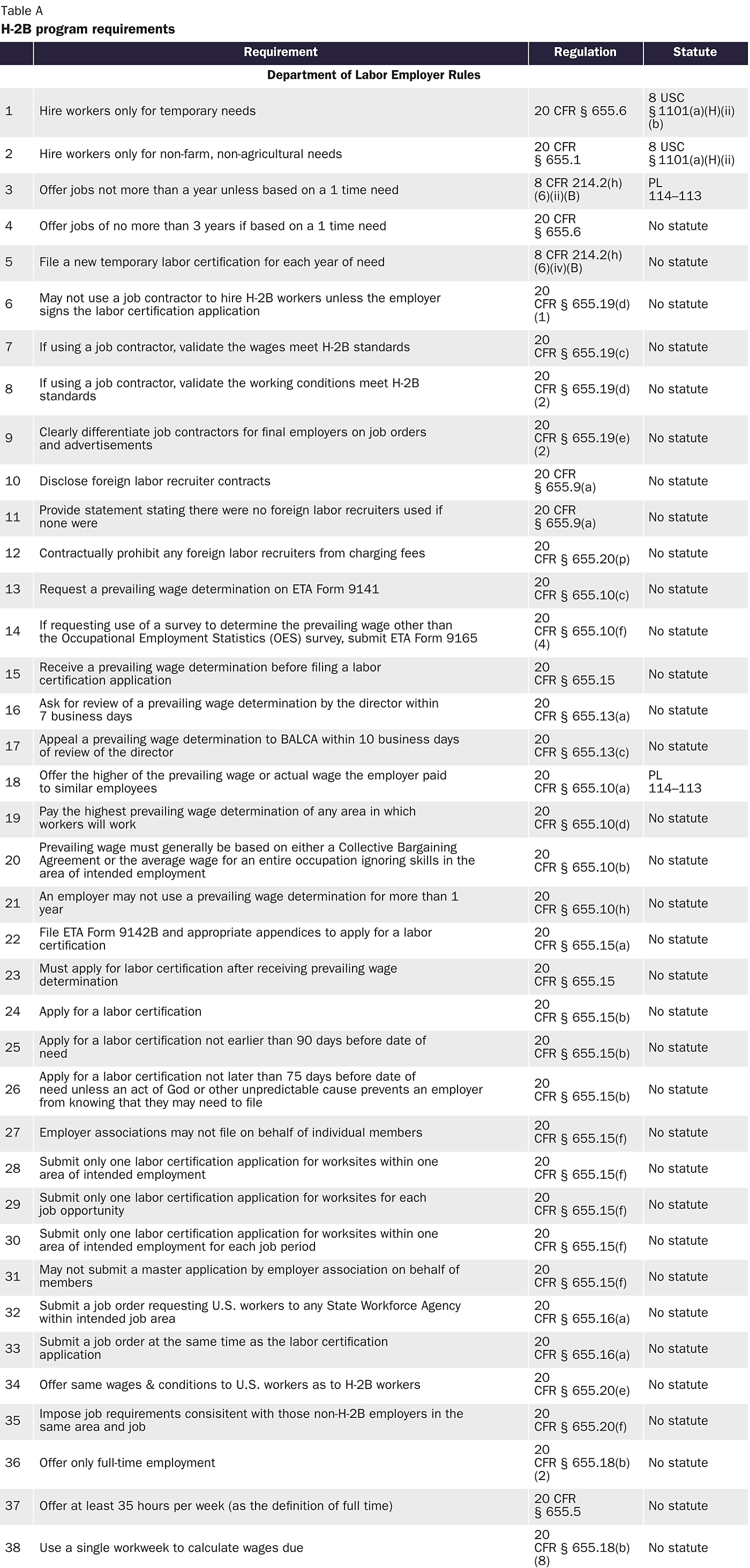

In most cases, the jobs that employers use the H‑2B program to fill require no formal education, but other than a prohibition on medical school graduates, there are no specific occupational or educational requirements.6 As an employer-sponsored program, businesses — not workers — initiate the H‑2B process, which is lengthy and complex. Figure 1 provides a broad outline of the H‑2B process, and Figure 2 provides a detailed path through all the steps for employers and workers in 2019. Appendix Table A provides a list of 176 H‑2B rules for workers and employers. These rules do not include the additional requirements for waivers from travel restrictions that were created in 2020 in response to the COVID-19 pandemic and economic downturn.7 The H‑2B statutes enacted by Congress are very brief; it is the agencies that are responsible for creating most of the H‑2B rules through regulation.

In 2008, the Department of Labor (DOL) supported the view that the H‑2B program had become “complicated, time-consuming, inefficient, and dependent upon the expenditure of considerable resources by employers,” but the agency has only added more rules since then.8 In 2014, the Office of the Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) Ombudsman characterized it simply as “highly regulated.”9 As a result, almost all employers hire attorneys or hiring agents to assist with the H‑2B process, at a cost of about $2,500 to $4,000 per application, plus per worker fees.10

Prevailing Wage Determination: 130–150 days before job starts

Initially, when employers have jobs that they might need to fill with H‑2B workers, they must obtain a temporary labor certification (TLC) from DOL to determine whether or not there are sufficient qualified U.S. workers who will be available and that any employment of H‑2B workers will not “adversely affect” the wages and working conditions of similarly employed American workers.11

The first step of the certification process is for the employer to predict a worker shortfall and submit a prevailing wage determination (PWD) request to the DOL about 150 days before the job start date (Figure 2, Step 1).12 For new users, this means learning about the process and usually retaining a hiring agent even earlier. For other users, this means starting the H‑2B filing process even while the H‑2B workers whom they plan to bring back the next year are still working for them.

The PWD is DOL’s minimum wage rate for H‑2B employers and, outside the visa cap, it is the most important, contentious, and expensive rule, causing many employers to drop out of the legal process. In 2020, the average wage for H‑2B hourly workers was $14.09 — nearly double the federal minimum wage of $7.25.13 And H‑2B wages were higher than every state’s minimum wage by an average of 60 percent.14 Figure 3 shows the average wage in each state for H‑2B hourly workers in 2020.

The DOL bases the prevailing wage determination on either the employer’s collective bargaining agreement (i.e., union wages) or the average of U.S. wages within normal commuting distance in the same job category in the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ (BLS) Occupational Employment Statistics (OES) survey or, in 1 percent of cases, another survey that meets DOL’s strict criteria.15 The stated purpose of this process is to have DOL match the employer’s job duties and locations to the correct OES wage. For unstated reasons, DOL has decided to monitor H‑2B employers more closely than it monitors H‑1B employers, which may simply look up H‑1B high skilled workers’ prevailing wages and skip this process entirely.16

In three ways, the PWD raises the H‑2B wage higher than the wages of most similar U.S. workers. First, DOL bases the PWD on the mean (average) rather than the median (i.e., the exact midpoint of the wage distribution, with half above and half below).17 But for 97 percent of OES occupational categories, a few unusually high-paid workers skew the averages to the higher end of the distribution.18 This means H‑2B wages are greater than the wages of a majority of U.S. workers in those jobs. Second, DOL requires that employers pay the highest average wage that could apply in the area of intended employment — that is, normal commuting distance from any of the job’s worksites.19 Work could be performed solely in one county with a lower average wage, but because DOL deems it within “normal commuting distance” (a phrase with no specific criteria or statutory basis) of a higher-wage county, employers must pay the higher wage.20

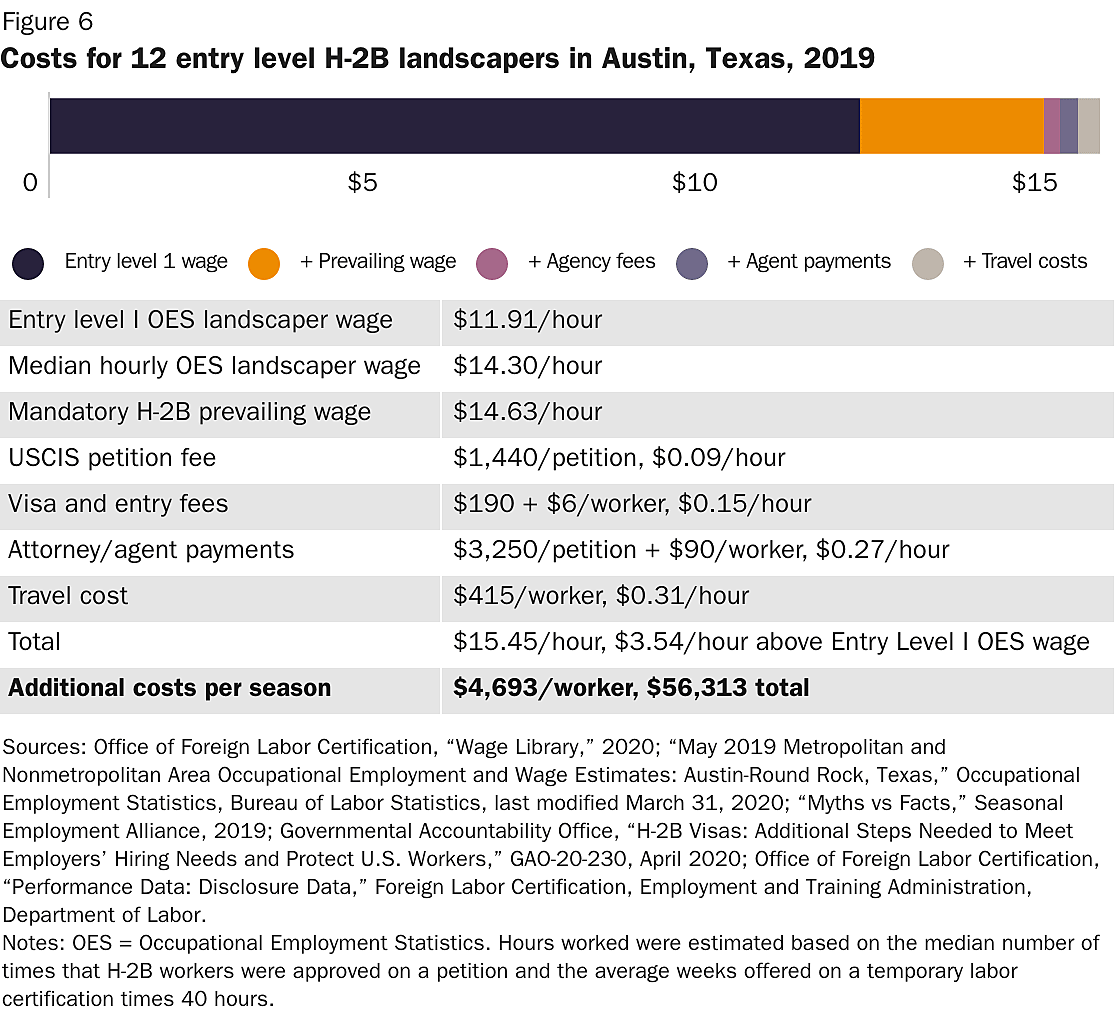

Third, and most importantly, the PWD fails to consider skill or experience differences within a job category.21 From 1998 to 2013, DOL provided wage levels (first two, then four) and assigned the PWD’s wage level based on the skills or experience that employers required. The agency still provides four wage levels for the H‑1B high-skilled visa and permanent visa programs, including for common H‑2B job categories, but in 2013 it stopped using skill levels in the H‑2B program in order to raise wages.22 The DOL had previously deemed about three-quarters of H‑2B jobs entry level, so by eliminating wage levels, it forced the wages of H‑2B workers higher than the wages of the majority of similarly skilled U.S. workers. For instance, in 2020 the PWD for a landscaper in Austin, Texas, was 23 percent higher than the wage for U.S. landscaper’s entry level wage in that area.23

The PWD is difficult for employers for reasons beyond its cost. Employers must identify all potential job duties and all potential worksites more than five months in advance. This effectively locks workers into the area of normal commuting distance from the jobsite and to a given job category. To understand how tricky this can be, a construction laborer, for example, may operate a cement mixer, but the moment the laborer steps down to smooth the cement, he becomes a cement mason with a higher wage requirement.24

While it is possible to obtain multiple PWDs to allow workers to perform multiple job duties at different wages, it is very burdensome to calculate each hour under different rates and keep jobs entirely separate in that manner.25 Individual workers cannot simply switch between categories throughout the job period as needed. The DOL will also not certify a job that crosses multiple commuting areas, except for forestry and carnival jobs.26 The PWD requires extensive and constant monitoring by supervisors so that employers do not violate H‑2B rules by having workers hired through the H‑2B process travel outside the area or take on any new job tasks.

Job Order and Temporary Labor Certification: 90 days before job start

Between 75 and 90 days before a job starts, employers must submit a job order to a State Workforce Agency — a federally funded state agency that helps unemployed U.S. workers — requesting that it advertise the job at the prevailing wage determination and refer U.S. workers to the job (Figure 2, Step 2).26 The state agency will ensure that the job order meets H‑2B requirements and report any deficiencies to DOL within six business days.28 All jobs must be “full-time,” defined (since 2015) as 35 hours or more per week.29

At the same time, the employer will apply for a temporary labor certification to DOL (Step 3) that contains evidence of the employer’s temporary need, defined as a “one-time occurrence; a seasonal need; a peakload need; or an intermittent need.”30 A temporary job cannot last longer than 36 months for a one-time need or generally not more than one year for other needs, although the exact length is based on the employer’s evidence.31 If the need is temporary but recurring year-after-year, employers may not seek only workers who will commit to return each season, and DOL will not certify the job for more than the upcoming season.32 The average H‑2B job period was eight months in 2020, with less than one-third of a percent certified for more than one year.33 The temporary requirement limits the types of H‑2B employers more than any other constraint because it rules out all indefinite, year-round positions.

If DOL decides that the need is temporary and that the job order meets the H‑2B requirements, it issues a Notice of Acceptance that requires the recruitment of U.S. workers, although H‑2B employers will generally have already started advertising the jobs voluntarily.34 Besides the job order, the employer must try to recruit U.S. workers by at least contacting former employees and posting the job at the jobsite within 14 days of the notice of acceptance (Figure 2, Step 4).35 The employer must accept all qualified U.S. applicants until 21 days before the job starts.36 The most prominent difficulty that arises for employers in this recruitment period is that some U.S. workers apply without actually wanting the job.37 This may happen because, if the state workforce agencies refer U.S. workers who are on unemployment benefits, those workers must generally pursue the opportunity in order to keep receiving their benefits.38

Unfortunately, the full scope of this “disingenuous applicant” problem is unclear because DOL does not systematically track how employers ultimately fill their H‑2B jobs. A survey of H‑2B employers in 2011 — when the unemployment rate was 9 percent — reported that only 6 percent of U.S. applicants for H‑2B jobs stayed for the full job period.39 In a typical example, the Small Business Administration’s Office of Advocacy mentions one Maryland landscaper that advertised 25 H‑2B jobs: 25 U.S. workers applied, 3 showed up for interviews, and only 2 lasted more than two weeks on the job.40 These disingenuous applicants can seriously damage U.S. employers’ recruitment efforts, and the lengthy certification process, combined with the visa cap, makes it nearly impossible to correct. Employers cannot charge any fees to workers to hold the job for them, so employers must accept the full cost of a U.S. worker abandoning a job offer, such as lost productivity and additional recruitment.41

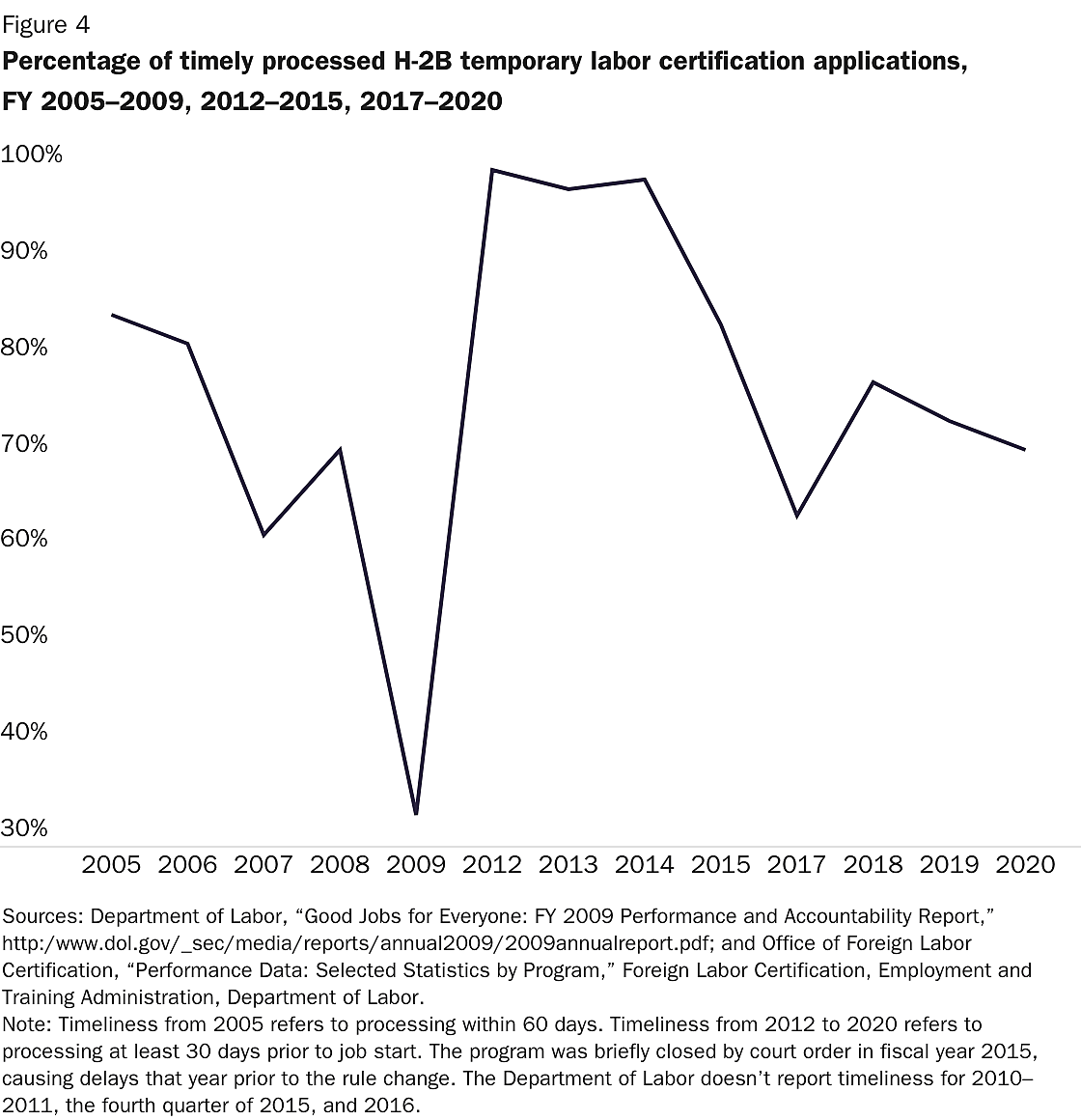

After at least 15 business days of posting the job at the jobsite (30 days during the COVID-19 pandemic), employers submit a recruitment report detailing the results of their efforts and requesting the right to hire H‑2B workers (Step 5).42 The DOL tries to process the temporary labor certification at least 30 days before the job starts.43 As Figure 4 shows, however, DOL routinely misses this processing target. The agency briefly made progress by instituting an expedited review process in 2009 and creating an online application in 2012, but it stopped the expedited reviews in 2015.44 By 2020, DOL failed to complete 29 percent of TLCs on time.45 In 2018, a DOL inspector general audit found that the agency “could not demonstrate that it processed H‑2B applications so that employers could obtain foreign workers by their date of need” and that its delays “have serious adverse effects on business owners and local economies.”46

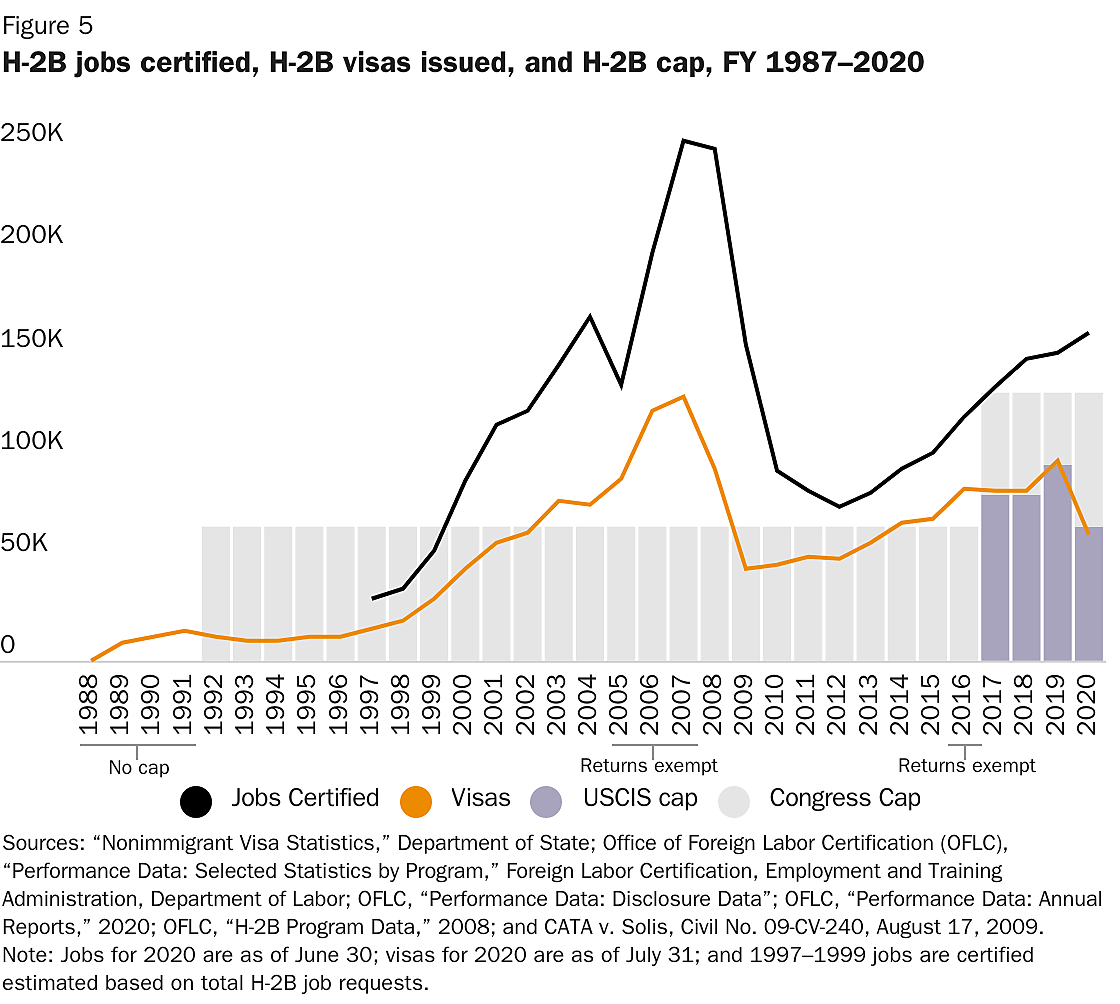

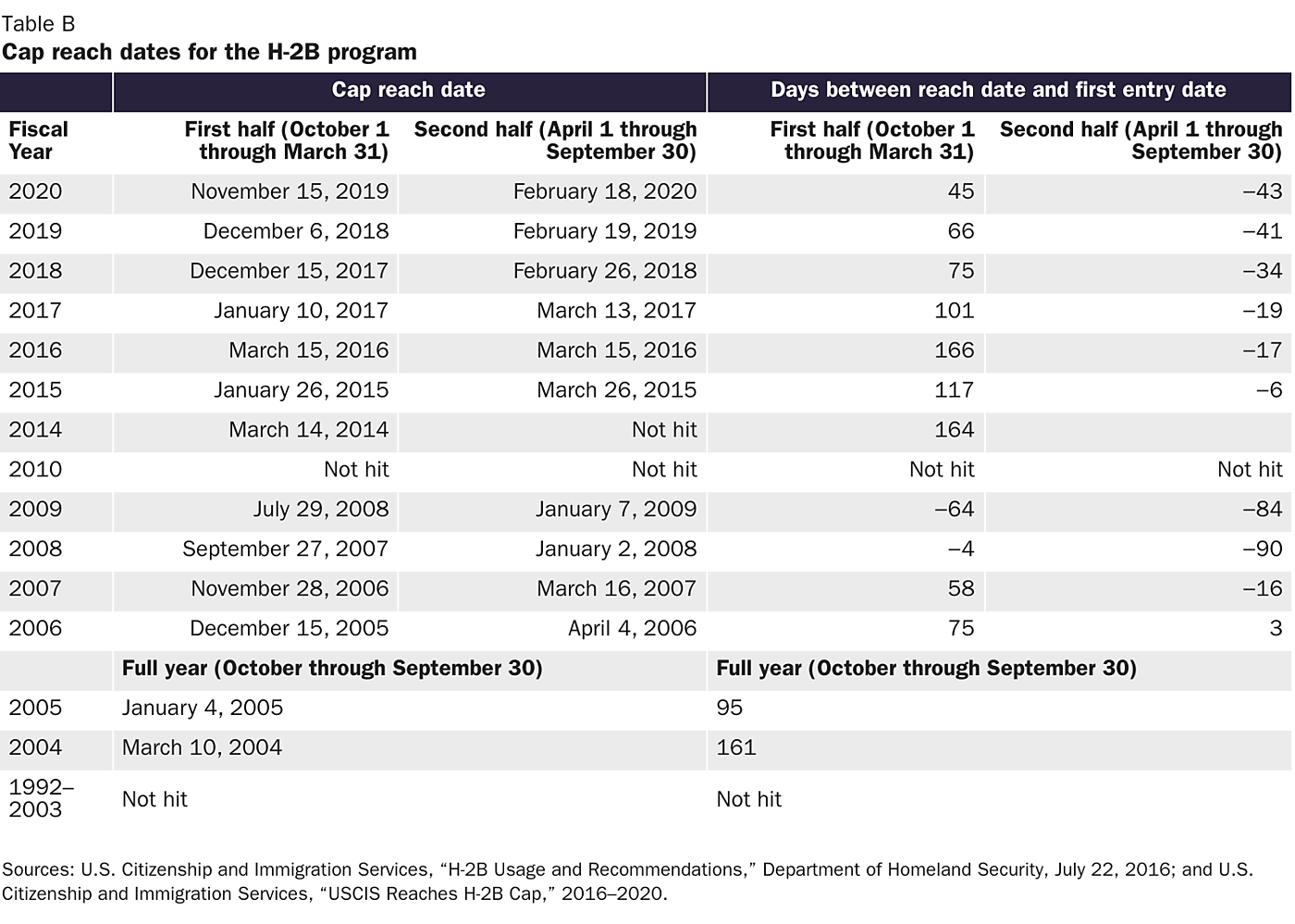

The H‑2B visa cap significantly affects DOL processing. In 1990, Congress capped the number of H‑2B workers who can receive an H‑2B visa abroad or status in the United States at 66,000 (starting in 1992).47 Since 2006, the cap has been equally divided between the two halves of the fiscal year.48 In recent years, the first-half cap (October to March) has been reached after the start of the fiscal year (e.g., in November 2019), but the second-half cap (April to September) has been filled almost immediately before the start of the half-year (see Appendix Table B). Almost all employers who are seeking workers subject to the visa cap during April to September list their job start dates for exactly April 1 so they can get in line first. The earliest that employers may apply to DOL for an April 1 date of need is January 1, so most do that, hoping to bump their petitions to the front of the line.49 In other words, legal — rather than economic factors — set employer’s job start and application filing dates, causing an unnatural rush on a single day. The H‑2A program for farmers avoids this problem by not having any cap.

On January 1, 2018, DOL received so many applications that it was slow to issue Notices of Acceptance, delaying the next step in the process. In response, DOL announced that it would certify TLCs in the order that they were filed rather than the date of the recruitment report, stating that it was fairer to preserve the filing order.50 The next year, at midnight on January 1, 2019, so many employers tried to submit applications that the online filing system crashed for a week, so in 2020, DOL used a lottery to decide the processing order.51 Temporary labor certifications placed through the lottery toward the back of the processing order simply never had a chance to be approved in time to file a petition before the cap was reached. These delays were also problematic for employers seeking to hire H‑2B workers who were not subject to the cap because their workers would arrive late.

The DOL denied 9 percent of all labor certifications in 2019, which is lower than the 15 percent it denied in 2012, but during that time many more employers withdrew their applications before processing — from 0 percent in 2012 to 9 percent in 2020.52 If DOL has not yet certified a TLC, and the opportunity to apply under the H‑2B cap has already passed, employers may withdraw the application to avoid having to pay the PWD to all U.S. workers that they hired. If DOL does process a temporary labor certification and agrees that U.S. workers have not filled all the jobs, it will certify any open jobs, thus allowing employers to recruit and hire H‑2B workers, although they must still accept state workforce agency referrals of U.S. workers until 21 days before the job starts.53

U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services Employer Petition: 30 to 60 days before job start

As soon as DOL certifies a temporary labor certification, employers may submit a petition to USCIS, a component of the Department of Homeland Security, requesting that it admit or grant status to H‑2B workers (Figure 2, Step 6). Before substantively reviewing the petition, USCIS will first decide if the requested workers will be subject to the H‑2B visa cap and, if so, whether a cap number will be available.54 The cap applies to workers who are “issued visas or otherwise provided nonimmigrant status” in a single fiscal year, and it counts workers receiving H‑2B visas, the first entry by a visa-exempt H‑2B worker, and those changing to H‑2B status in the United States from another status.55 The cap excludes workers extending their H‑2B status; those previously counted toward that year’s cap; those returning to a job under the same visa or approved petition; workers in the territories of the Northern Mariana Islands or Guam; and fish roe processors, technicians, and supervisors (entirely in Alaska).56

If USCIS estimates that the cap will be filled based on the number of petitions it receives within the first five business days after employers start applying, the agency conducts yet another lottery (occurring after DOL’s lottery) to determine which petitions to process.57 The lottery selects entire petitions — which include all the workers that an individual employer is seeking — rather than selecting individual beneficiaries from each petition.58 This means that employers either receive all their workers or none. Unlike the DOL lottery, unselected petitions are simply returned and are not processed later.59 Employers, however, must still fulfill all the DOL requirements with respect to any U.S. workers hired or referred under the H‑2B job order, effectively penalizing the H‑2B cap losers.60

While it has not permanently updated the visa cap, Congress has attempted to alleviate the cap in the years with the highest demand. In May 2005, Congress exempted (from the 2005 and 2006 caps) all returning workers who had counted against the cap in any of the prior three years — a policy that was extended into 2007.61 Demand subsided below the cap when unemployment spiked following the Great Recession, but after the recovery, employers reached the cap again in 2014 and 2015, prompting Congress to reenact the returning worker exemption in 2016.62

For 2017, Congress enacted a temporary provision authorizing USCIS to increase the cap to 130,716 — equal to the most visas and status ever issued in any year (2007) — if it determined that American business needs were unmet.63 It reenacted this provision for 2018, 2019, and 2020; the administration raised the cap by 15,000 in both 2017 and 2018 and 30,000 in 2019 and restricted the visas only to businesses that would face irreparable harm without workers.64 For 2019, USCIS made only returning workers eligible, and in 2020, after initially offering 35,000 more visas, USCIS retracted the offer.65

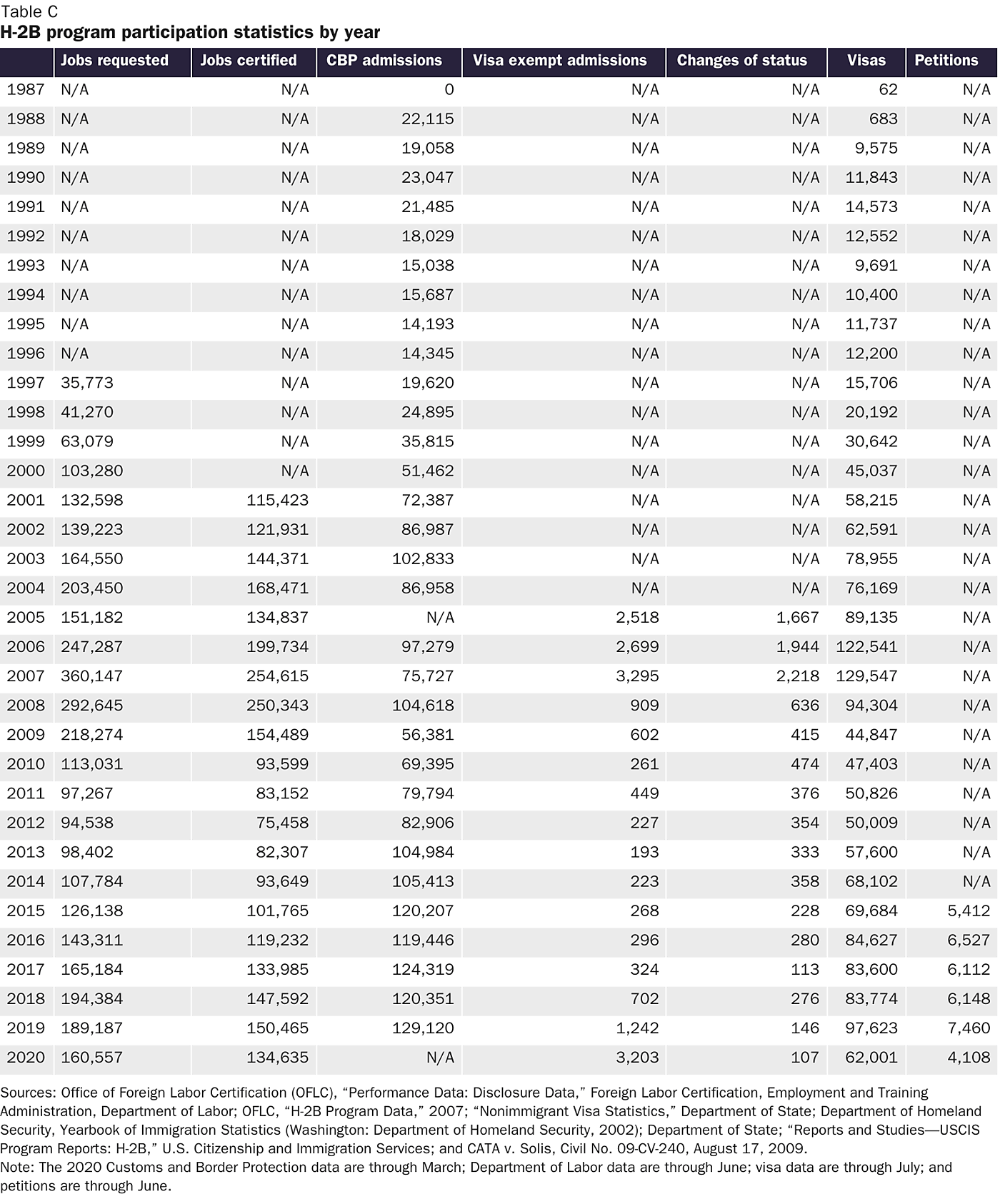

Figure 5 summarizes the changes in program participation and shows that the most growth occurred from 1998 to 2007 (see Appendix Table C for additional data). The cap was first hit in March 2004.66 As demand grew, Congress waived the cap for returning workers from 2005 to 2007.67 In recent years, however, USCIS’s refusal to increase the cap to the extent authorized by Congress has clearly constrained the program’s size. In 2019, DOL certified 150,465 H‑2B positions, and the State Department issued 97,623 H‑2B visas (just 146 workers changed to H‑2B status in the United States in 2019).68 In 2020, the disparity was even greater.

Employers selected in the USCIS lottery may later petition for unspecified workers to be specified by name later at a consulate for a fee of $460.69 For specifically named workers, the fee is the same even though USCIS must conduct a background check on each worker (unnamed workers receive their background checks at the consulate). Generally, petitions cover all the requested workers.70 Instead of the standard fees, however, nearly all H‑2B employers pay a $1,500 premium processing fee, which USCIS promises will guarantee processing in 15 business days.71 Despite this guarantee, the agency can restart the 15-day clock by issuing a Request for Evidence (RFE), thus delaying the timeline, as happened in 17 percent of its 2019 cases.72

For unnamed petitions, USCIS only reviews whether the job meets H‑2B require-

ments — mainly whether it is temporary.73 This process is entirely duplicative of the TLC, and the agency’s ombudsman has repeatedly found that USCIS often sends RFEs asking for evidence that was already provided to USCIS or incorrectly asserting that a need may not be temporary if it recurs every year.74 While USCIS has improved in recent years (see Appendix Table D), these requests are still common, even though the agency denied just 1.6 percent of H‑2B petitions in 2019.75

Visas, Admission, and Employment: 0 to 14 days before job starts

If USCIS approves a petition and employers finish accepting U.S. workers, then employers can recruit foreign workers (Figure 2, Step 8). Workers must ordinarily apply for H‑2B visas to the State Department at a U.S. consulate or embassy if they are abroad (Step 9). Canadians, as well as Bahamians and Bermudians, are exempt from the visa requirement.76 In June 2020, a presidential proclamation suspended the issuance of visas to H‑2B workers who had no valid visas in June 2020 unless the workers sought and received waivers showing that they are returning to employers that trained them, or unless the denial would cause their employers hardship.77 The proclamation is effective until March 31, 2021, but could be renewed.

Each H‑2B worker pays a $190 visa processing fee, which employers must either advance or reimburse within the first week.78 Usually, consulates must fingerprint and interview each applicant, although these can be waived for workers returning within 24 months.79 H‑2B visas are valid for multiple entries but only for the same period as the petition, necessitating a new visa for each new job if workers return home.80 If visas were valid for a longer period, fewer workers would count against the H‑2B visa cap.

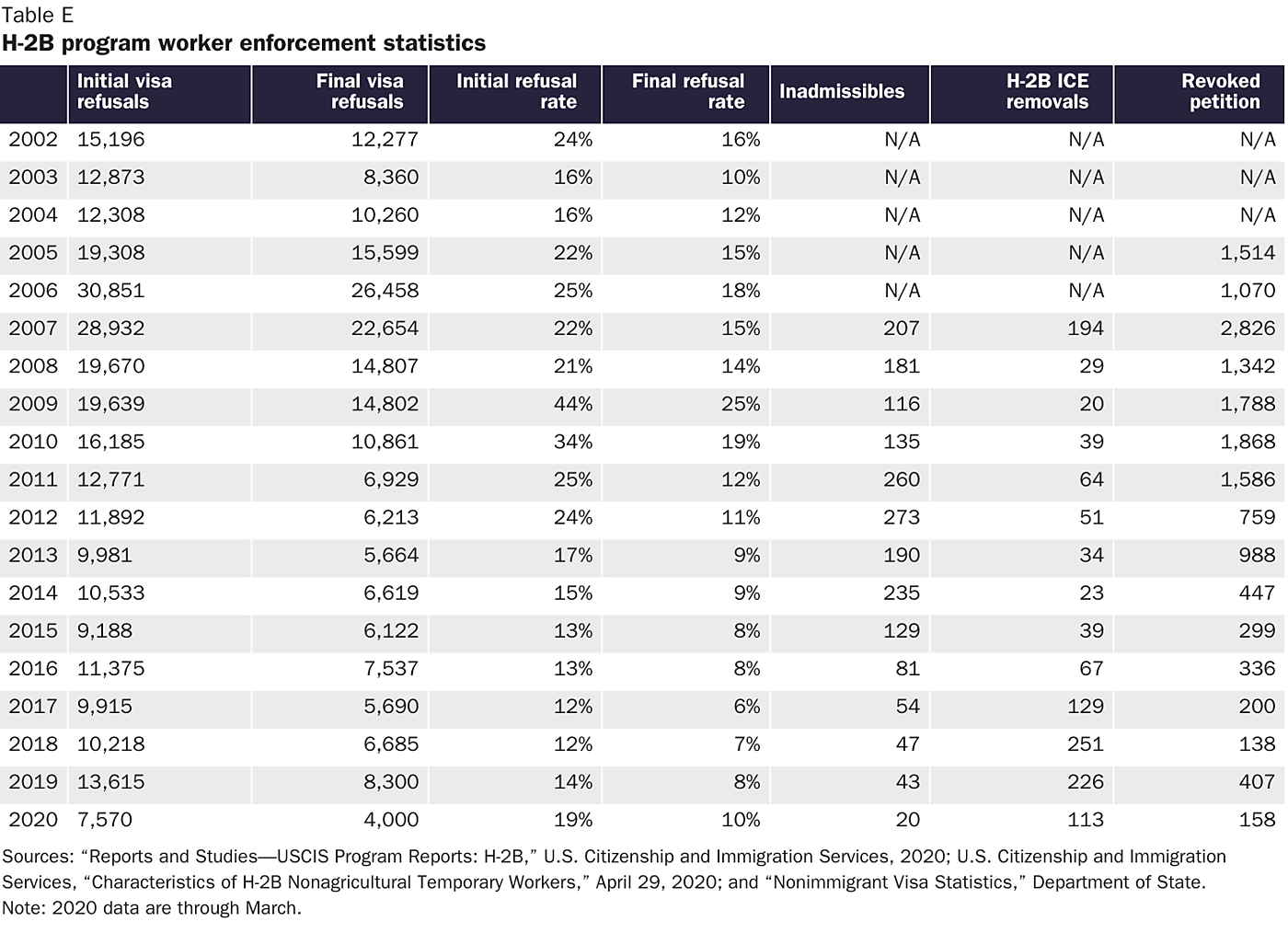

The visa application can also delay workers. In 2020, consular officers refused 19 percent of H‑2B visa applicants, but after the applicants submitted additional evidence the final refusal rate fell to 10 percent.81 These rates have fallen from highs of 44 and 25 percent, respectively, in 2009 (see Appendix Table E). The State Department does not publish specific reasons for these refusals,82 but the primary purpose of the visa process is to prove “nonimmigrant intent” — that is, proof of strong ties to the worker’s home country that would motivate the worker to return home — so this requirement likely accounts for most denials.83

However, other issues can arise. The USCIS ombudsman reported a case where, in 2012, a consular official initially rejected workers because he felt that they could not adequately explain their job duties, thus risking $1 million in contracts for a U.S. landscaper, until the ombudsman intervened.84 The ombudsman has said that “delays at any point in [the H‑2B] process can have severe economic consequences for U.S. employers.”85 Unfortunately, the federal government does not track how often guest workers arrive after the start date.86

Visas authorize travel to the U.S. border, where Customs and Border Protection (CBP), another agency within the Department of Homeland Security, screens workers and grants them admission (Figure 2, Step 14). Workers receive an entry document (I‑94) authorizing their H‑2B status for the job’s duration, plus up to 10 days to travel to the job and 10 days to travel back home or find a new job.87 Importantly, the fact that the regulation entirely ties the length of status to the TLC’s job length ensures that all returning workers who leave the United States are counted against the cap every year whenever they return under a new petition.88 CBP charges an entry fee of $6 per worker, which employers must repay, and workers often wait in line several hours to enter the country.89

When workers do start, employers must guarantee that they will pay three quarters of all hours offered at the prevailing wage determination for three-quarters of every 12-week period of the job at 35 hours per week — even if the job finishes early — to both H‑2B and U.S. workers in “corresponding employment.”90 Objecting to these requirements, Congress has repeatedly prohibited DOL from using funds in each congressional appropriations law that it has passed since 2015 to enforce both the “three quarters guarantee” (for all workers) and the “corresponding employment rule” (for U.S. workers not hired through the H‑2B job order process).91 Should Congress allow DOL to enforce the rules, the agency claims that it will target employers for violations in prior years.92

Beyond the prevailing wage determination, these requirements are the most complex and expensive of H‑2B’s major rules (see Text Box 1). The three-quarters guarantee imposes significant risk for employers if a job completes early or cannot start on time, which is very difficult to predict months in advance. Commenting on this rule, the Small Business Administration’s Office of Advocacy noted, for example, that “forestry contractors cannot schedule tree planting in advance because the weather changes for weeks at a time — the ground can be too hot, too frozen, too wet or too dry to plant.”93 Because all jobs on a temporary labor certification must occur during the exact same period, employers also cannot stagger the entry of H‑2B workers as they ramp up operations. Seafood employers can use staggered entries but only because Congress forced DOL to allow them to.94

Text Box 1: Major H‑2B Rules

- Eligibility: Full-time nonfarm jobs lasting no more than one year or three years for a one-time need

- Prevailing Wage Determination (PWD): H‑2B minimum wage based on local averages that exclude skill differences

- H‑2B cap: An annual limit of 66,000 on H‑2B visas or status

- Job Order: A request for U.S. workers from a State Workforce Agency

- Temporary Labor Certification (TLC): Prove temporary need, recruit U.S. workers

- Recruitment report: Document job offers to past U.S. employees, posting of job offer, inter- views with U.S. workers

- Visa: Workers must receive a visa from a consul- ate to travel to a U.S. port of entry

- Petition: Employers must petition to request worker entry to the United States

- Corresponding employment rule: U.S. workers receive same benefits as H‑2B workers

- Three-quarters guarantee: pay at least 75 per- cent of offered wages in each 12-week period

- Housing: provide and pay for housing for mobile workforces (forestry, carnivals, etc.)

- Transportation: Cover daily transit to and from home country or state

- Meals: Workers must receive three meals per day during transit from abroad

- Three-year limit: H‑2A workers transferring be- tween U.S. farms must return for 90 days after three years

- Fees: $150 Fraud Fee; $460 per petition; $1,500 for 15-day premium processing; $190 per visa; $6 per admission

Source: See Appendix Table A for a full list of 176 rules.

Because the guarantee applies to each 12-week period (cut to 6 weeks if the job period is less than 120 days), it is less flexible than a similar H‑2A rule for farmers, which applies to the entire job period and so allows farmers to make up missed hours during peak periods.95 If employers fail to report within two days when both H‑2B and corresponding U.S. workers leave the job, the employers must pay the workers for the time that they were originally scheduled to work, even if the workers left on their own.96 The guarantee necessitates very close monitoring of what hours were offered, why hours were not worked, and what hours were worked in every 12-week period for every worker — burdensome tracking for small employers.97

The corresponding employment rule is the second most expensive H‑2B requirement after the prevailing wage determination because it imposes the H‑2B program’s major costs on the entire workforce in the area, mandating the inflated PWD and benefits to nearly all similar U.S. employees.98 For employers where the H‑2B workers would represent, for example, half the workers in a job category, this rule doubles the PWD’s cost. The rule is also exceptionally burdensome for employers that would typically have employees performing a shifting array of tasks throughout the year, so identifying who qualifies as a “corresponding” worker is difficult. As soon as they employ H‑2B workers, the employers must carefully monitor their tasks to guarantee that they avoid inadvertently becoming a “corresponding” worker.99

Since 2015, employers of itinerant H‑2B workers (mostly in forestry and carnivals) have had to provide housing at no cost to the workers.100 For forestry and carnivals, this is the biggest burden other than the prevailing wage determination because it raises their compensation even further above the pay for U.S. workers not hired through the H‑2B process, where free housing is rarely provided. After workers complete 50 percent of a job, employers must reimburse their expenses for travel to the jobsite and, if workers complete the job, pay for the trip back to their home unless workers find other H‑2B jobs.101 Again, employers must do this for both H‑2B and U.S. workers because all H‑2B benefits on the job order must be offered to U.S. workers. Employers must calculate the market rates for bus or air fare, lodging, and meals for each day, including those days spent traveling to and staying in the city with the U.S. embassy or consulate waiting for visa approvals.

The travel costs are also a significant added expense of the H‑2B program. Figure 6 summarizes a rough calculation of the typical, added cost for an H‑2B employer in Austin, Texas — the city with the most H‑2B jobs. Because the PWD is based on the local wage, it is important to make these comparisons at a local, rather than national, level.

After the job ends, employers must maintain records for three years and cooperate with audits and investigations to avoid fines and debarment from the program.102 The H‑2B program has two overlapping enforcement processes.103 First, DOL’s Office of Foreign Labor Certification (OFLC) — the same DOL component that adjudicates the temporary labor certification — conducts random audits of H‑2B employers at a rate of about 7 percent annually.104 OFLC reviews employer documents and can require additional recruitment measures or debar employers.105 Most H‑2B employers are small businesses with limited human resources staff, making random audits without any alleged violations a burdensome exercise.106

Second, DOL’s Wage and Hour Division (WHD) may independently conduct investigations based on complaints, prior violations, referrals from other agencies (including OFLC), or other reasons, such as fraud trends.107 An investigation is typically lengthier and more intrusive than an audit, involving onsite visits and interviews with employees.108 The division may assess civil monetary penalties for violations that are willful and for substantial failures to follow H‑2B rules.109 It may also order backpay to both U.S. and H‑2B workers or debar employers for up to five years.110

After their jobs end, regulations require H‑2B workers to find another employer within 10 days or return home.111 The rules also mandate absences of at least three continuous months for every three continuous years of status (except during the COVID-19 pandemic for workers in food processing).112 In 2015, DHS assumed that half of H‑2B workers extended their stays for at least one year and a quarter of workers extended their stays for three years.113 This suggests a total H‑2B population of 160,410 in 2019.114

Employers and the H‑2B Program

The DOL has recently stated that “H‑2B workers play a vital role in the U.S. economy by reducing the negative economic impact of labor shortages in several important industries.”115 The significant expenses and uncertainty about the availability of visas, however, limit the H‑2B program only to employers with significant needs for temporary labor that can be predicted very far in advance. In 2019, about 6,222 U.S. employers submitted H‑2B temporary labor certification applications — less than 1 percent of all U.S. employers — and only about half of those received approved petitions for cap-subject nonimmigrant workers.116 Without knowing exactly how often the cap prevents employers from filling H‑2B jobs, it is difficult to assess the full economic effect of the H‑2B program, but in 2019 employers offered these workers total wages of about $4.7 billion.117

Figure 7 shows the number of DOL-certified jobs by job type for fiscal years 2000 to 2020. In 2020, the agency certified H‑2B jobs under 196 job codes, but seven categories dominated the program. Of the 2020 H‑2B jobs, 46 percent were for landscapers, 7 percent for forestry workers, 7 percent for meat and seafood cutters and trimmers, 6 percent for maids, 6 percent for amusement attendants, 2 percent for servers, 2 percent for construction workers, and 24 percent for all other jobs.

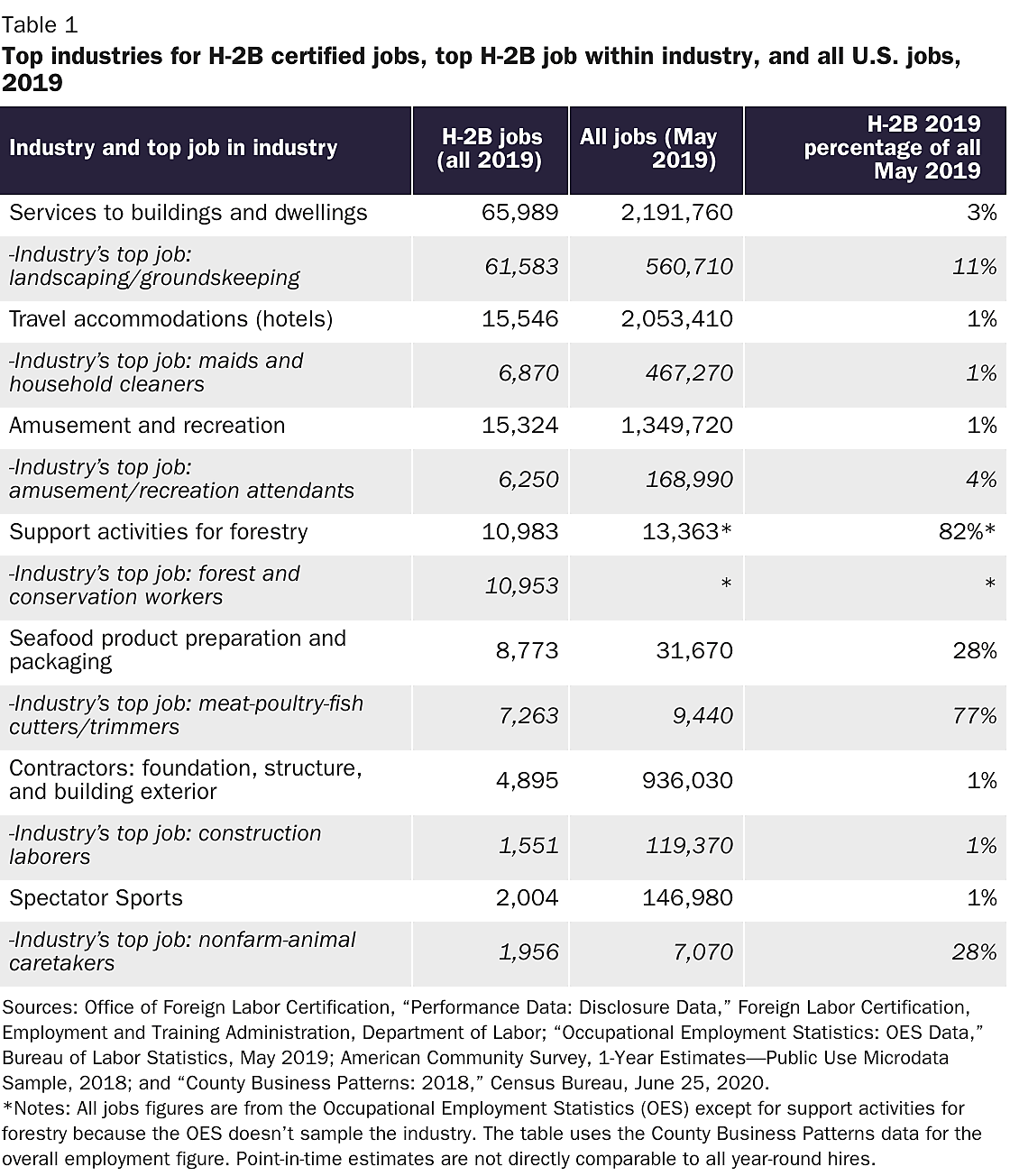

Table 1 shows the top industries for H‑2B certified jobs in all of 2019 and the top job within those industries compared with the U.S. totals for a single month in 2019. These statistics are not perfectly comparable because only about 82 percent of H‑2B jobs occur in the month of May. Nonetheless, these are the best statistics available to contextualize H‑2B’s importance within each industry and category.

The industry most dependent on H‑2B workers is the industry “Support Activities for Forestry,” where H‑2B certified jobs for forestry and conservation workers in 2019 accounted for about 82 percent of the industry.118 The seafood industry is also almost entirely dependent on H‑2B workers as its cutters and trimmers. H‑2B jobs account for nearly a quarter of animal caretaker jobs in the spectator sports industry (mainly horse racing). At 11 percent of the jobs in the industry, landscapers play as significant a role in the services to buildings and dwellings industry as H‑2A temporary foreign workers do on U.S. farms.119 While not highly represented in the amusement industry overall, H‑2B amusement attendants are important at traveling carnivals and fairs, and construction laborers and maids often fill niches in resort towns or sparsely populated parts of the country.

In other industries, H‑2B visas can play a very small role for a variety of reasons besides limited employer needs. The building construction industries, for instance, employ three times as many workers as landscaping; however, they hire almost no H‑2B workers, possibly because they have trouble meeting certain specific requirements like predicting the number of workers needed months in advance.120

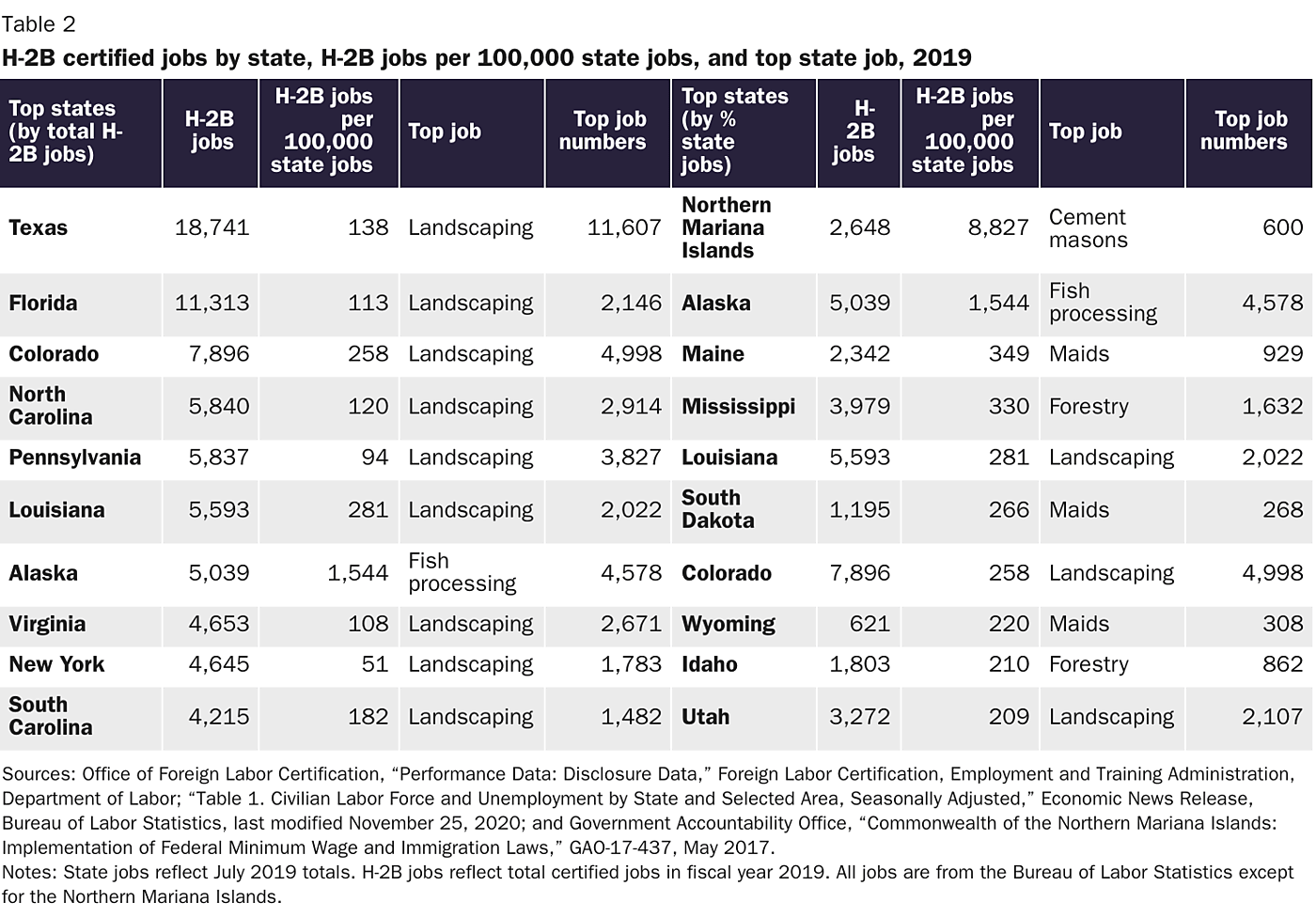

Table 2 shows the distribution of H‑2B certified jobs by state in 2019. In absolute terms, Texas led the way with 18,741 (12 percent of the total), followed by Florida, Colorado, North Carolina, and Pennsylvania. Landscaping was the top job in these states. In relative terms, however, the territory of the Northern Mariana Islands was by far the most dependent on H‑2B jobs, which accounted for nearly 9 percent of its jobs — with cement masonry being most common — partly because Congress waived both the H‑2B cap for the territory and the requirement that a job be temporary if it is related to military facility construction or health care.121

Alaska was by far the state most dependent on H‑2B jobs, with 1,544 H‑2B jobs per 100,000 jobs in the state. These were almost entirely in fish-related industries, which have benefited from a cap exemption for fish roe processing.122 Maine (maids); Mississippi (forestry); Louisiana (landscaping); and South Dakota (maids) followed, with between 266 and 349 H‑2B jobs per 100,000 jobs. The least dependent states were Hawaii, Connecticut, California, Nevada, and Wisconsin, with fewer than 20 H‑2B jobs per 100,000 jobs.

Employers only use the H‑2B program because they cannot find willing U.S. workers at the prevailing wage. Given this fact, the industries and locations of H‑2B workers make sense. Several states or territories with small populations are the most dependent on H‑2B workers because U.S. workers are least available there. H‑2B maids typically service remote locations such as Cape Cod or national parks during the relatively brief and intense summer seasons.123 H‑2B workers are also critical to traveling carnivals, where the jobs move from county to county.124 Similarly, forestry jobs require employees to work in a series of remote locations in extreme weather conditions, separated from family for months at a time.125 The Bureau of Labor Statistics states that forestry jobs are “physically demanding” and have “one of the highest rates of injuries and illnesses of all occupations.”126 Similarly, landscaping, fish roe processing, and crab picking can be physically taxing jobs with less favorable conditions than the ones that Americans generally fill. U.S. workers sometimes relocate to remote areas for work and often perform physically taxing work, but they appear far less likely to do so when the job will provide only a short, temporary period of employment.

H‑2B certified jobs have not attracted U.S. workers, despite DOL rapidly raising the prevailing wage since 2011. The average wage for hourly H‑2B workers rose by 39 percent from 2011 to 2019 — more than twice the increase in the average hourly wage for all U.S. jobs (18 percent) — yet DOL certified about twice as many jobs in 2019 as it did in 2011 (Figure 8), indicating that too few U.S. workers applied for those jobs. These wage increases partly reflect stricter prevailing wage determination rules in 2013 and 2015, but also faster-than-normal wage growth in all the top 10 H‑2B job categories, particularly landscaping (see Appendix Table F).

The unemployment rate in the top H‑2B jobs is almost always higher than the national average because these jobs are inherently temporary, so workers face more periods of unemployment, but those periods are shorter than they are for other workers.127 In 2019, the average length of unemployment for all workers was about 20 weeks, while the average for landscapers and construction was fewer than 14, maids fewer than 13, servers fewer than 10, and meat processors fewer than 5.128 Workers in temporary jobs are more likely to be unemployed at any given time, but employers snatch them off the market much faster, so it is common for workers to be unemployed but unavailable due to other commitments. Workers seeking temporary jobs often commit to another job soon after their present job concludes. This means that unemployment in temporary jobs indicates something entirely different from unemployment in other jobs, making it an unreliable gauge of labor market tightness.

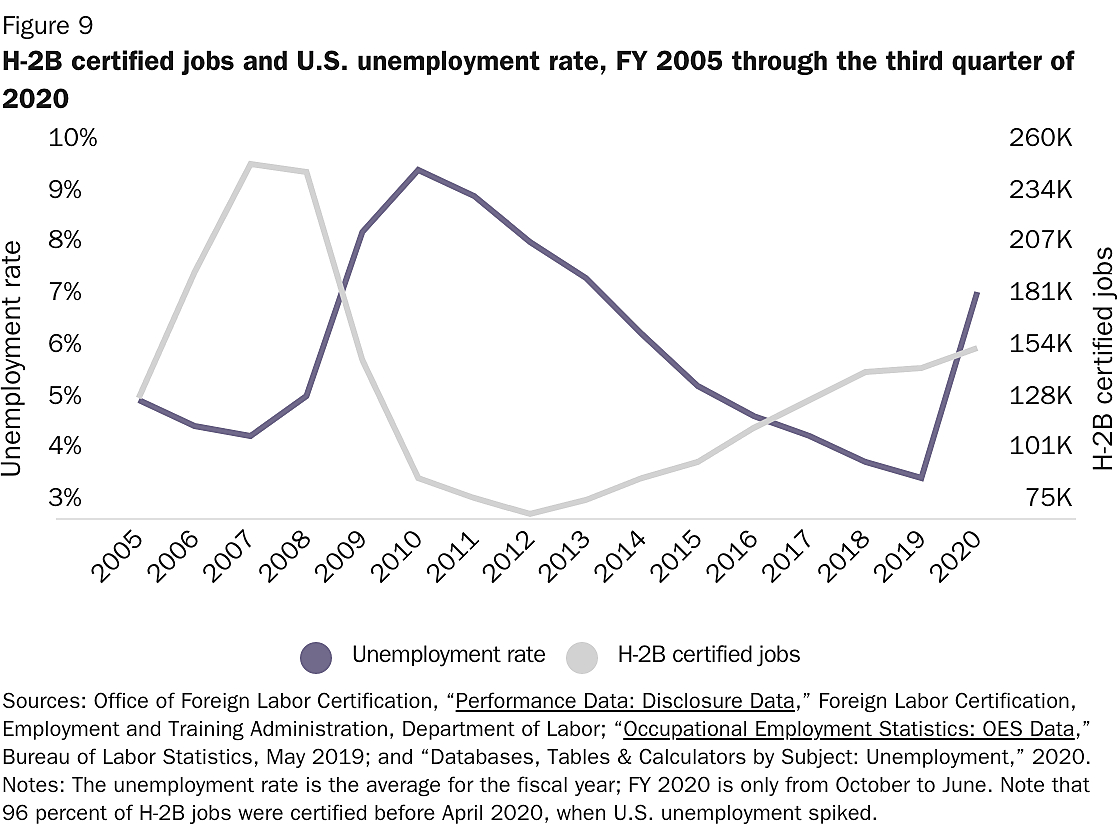

Except for the highly anomalous year of 2020, the number of DOL certified jobs has generally tracked the national unemployment rate for the last 15 years (Figure 9), indicating that H‑2B demand does respond to looser labor markets.129 The GAO has found that counties with H‑2B employers also had lower unemployment rates than other counties in every quarter from 2015 to 2018, as well as 15 percent higher wages.130 These findings are consistent with other, more sophisticated statistical research.131

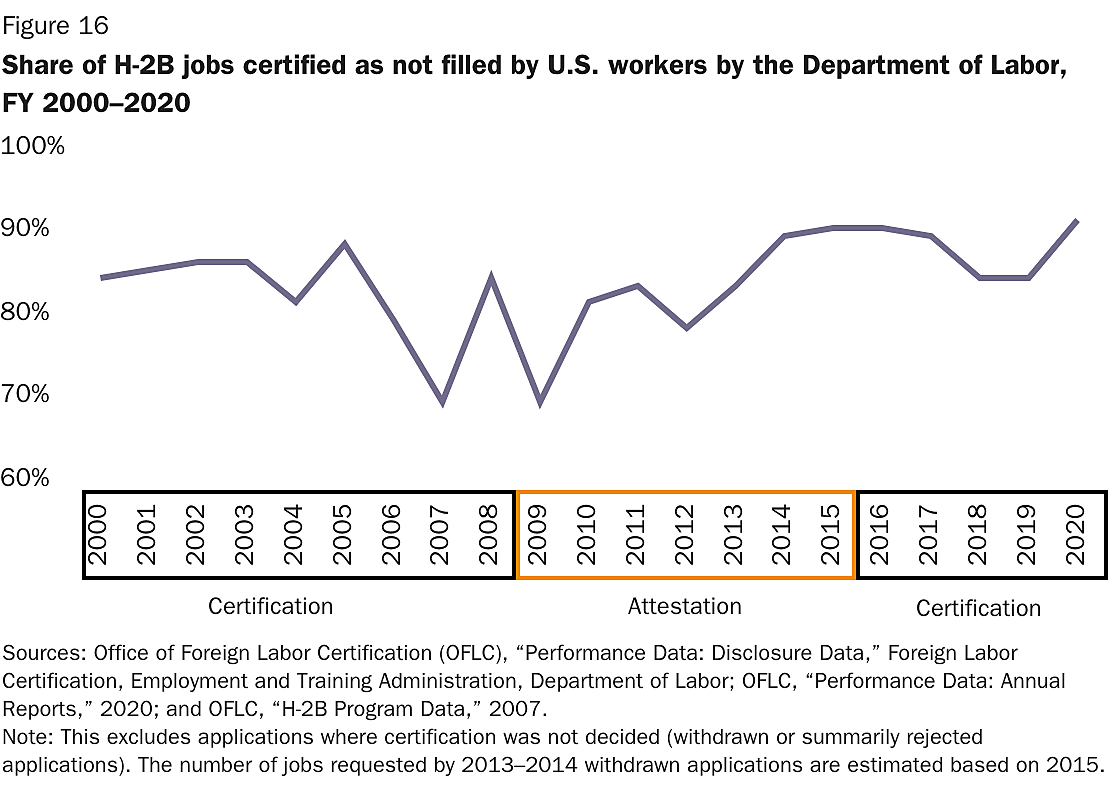

While employers do generally request fewer workers when unemployment is high, the rate at which U.S. workers apply for the H‑2B jobs that are offered hardly changes (see Figure 16 below). Unemployment peaked in fiscal year 2010, and H‑2B job requests plummeted, but DOL still certified 83 percent of jobs as unfilled by U.S. workers in that year as opposed to 86 percent in 2019 with a historically low unemployment rate.132 Employers only go through the H‑2B process when they are confident that they will not find U.S. workers.

Foreign Workers and the H‑2B Program

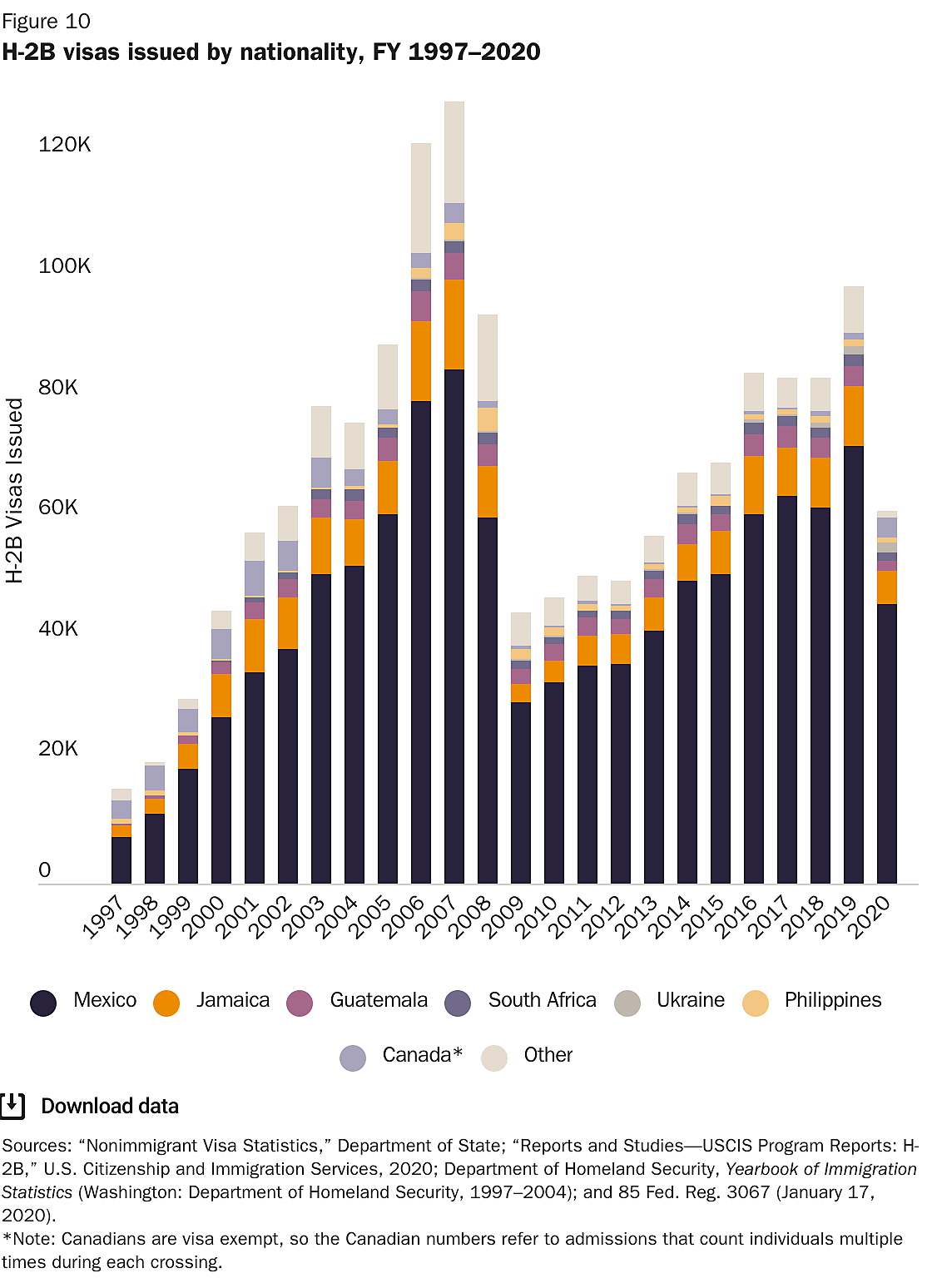

USCIS restricts H‑2B visas to nationals of 81 countries (companies must justify any exceptions based on unusual skillsets), and nationals of 74 countries participated in 2018 and 2019. Mexicans dominate the flow (Figure 10), with the Mexican share of visas increasing from 49 to 74 percent between 1997 and 2019. The next most common nationality in 2019 was Jamaican (10 percent), followed by Guatemalan (3 percent), and South African (2 percent). All other nationalities amounted to about 12 percent—a majority of which were from Eastern European countries such as Romania, Serbia, and Ukraine.

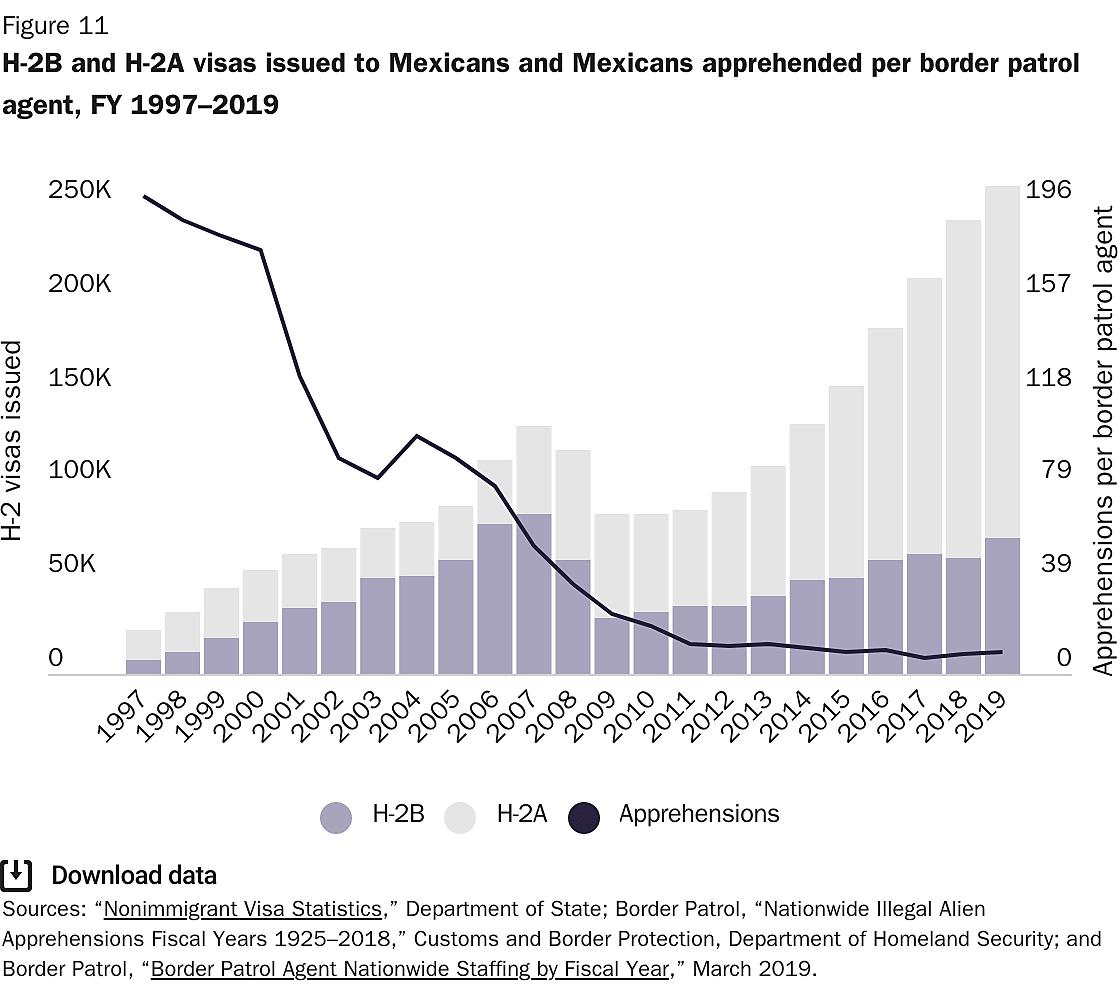

Since illegal workers also often seek jobs in common H‑2B categories, it makes sense that the increase in Mexican H‑2B workers has corresponded with a decrease in the number of illegal crossings by Mexicans. In 2019, each Border Patrol agent averaged 96 percent fewer apprehensions of Mexicans than in 1997, while the number of H‑2B and H‑2A visas for Mexicans increased elevenfold (Figure 11).133 Fewer illegal crossers fed the demand for more legal workers, and more legal workers led to even fewer illegal crossings—two mutually reinforcing trends. A 1 percent increase in H‑2 visas for Mexicans—including those under the H‑2B program for nonagricultural jobs and the H‑2A program for farm jobs—was associated with a 1 percent decline in the absolute number of Mexicans apprehended for crossing illegally.134 As one H‑2 worker said in April 2019, “Most of my friends go with visas or they don’t go at all.”135

Workers cannot apply directly for H‑2B visas. Businesses petition USCIS for foreign workers before workers receive visas, so employers ultimately control which countries the workers come from. As H‑2B employer requests grew, U.S. businesses simply expanded their existing recruitment in Mexico.136 If Congress wants to encourage the hiring of other nationalities that are prone to making illegal border crossings—such as Hondurans, Guatemalans, and Salvadorans—it needs to expand the program but restrict hiring only to those specific countries, thus forcing employers to recruit in those countries.137 The DHS initially set aside 10,000 visas from the 2020 H‑2B supplemental cap increase for workers from Honduras, Guatemala, and El Salvador before it decided to cancel the cap increase entirely.138

Higher U.S. wages and benefits motivate workers to accept U.S. jobs (see Text Box 2).139 The average wage for hourly H‑2B workers was $14.09 per hour in 2020, while the minimum wage in Mexico, for example, was just $4.64 per day—less than $1,200 per year.140 About 85 percent of H‑2B workers are men.141 Their spouses and minor children qualify for dependent H‑4 visas, but since family members must pay all their own expenses and USCIS prohibits them from working legally, nearly all workers leave their spouses and children at home. This separation creates significant hardship for guest worker families, which USCIS could prevent in some cases by authorizing spouses or older children to work.

Text Box 2: The U.S. Experience for H‑2B workers

“H‑2B’s a huge help. It’s what we Mexicans call ‘the American dream,” said Gallegos Alvarez, a Colorado horse caretaker from Mexico who worked in 2018. “l have felt very at ease working here I had hoped to further my family, create a home, build a house, and here I have succeeded,” said José Luis Cruz, a Pennsylvania landscaper who worked in 2019.

Behind every one of us, there are little ones who depend on us, emotionally as well as economically. We live half our lives over there and half our lives over here,” said Adalberto Espinoza, a Colorado landscaper and father of three who worked in 2017. “l don’t mind because the smell of crabs is the smell of money,” said Martha Olivares Garcia, who used the money she earned picking crabs in Maryland in 2019 to pay for her child’s education.

‘I’m not here to take anyone’s job I look at my hands and they’re bleeding, they’re hurt, they’re tired.… As long as we are offered work visas, then we’ll be here,” said Melva Guadalupe Vazquez who picked crabs in Maryland in 2019.

‘A lot of people had to stay in Mexico, because they couldn’t get an H‑2B… We all feel lucky to have jobs here,” said Jesus Escalante Martinez, a Minnesota horse trainer who worked in 2017.

Source: See endnote 139.

Additionally, H‑2B workers must prove “nonimmigrant intent” to the State Department in order to receive visas by “demonstrat[ing] permanent employment, meaningful business or financial connections, close family ties, or social or cultural associations, which will indicate a strong inducement to return to the country of origin.”142 For workers who have few economic assets tying them to their home country and are seeking temporary jobs in the United States, close family ties to their home country may be their only way to demonstrate nonimmigrant intent. If the entire family is coming to the United States, many officials treat it as a sign that they will be likely to overstay.143

Some H‑2B workers do occasionally overstay their visas, but that is not a significant contributor to illegal immigration relative to other sources. The government deported 972 H‑2B workers from 2008 to 2019—just 0.05 percent of the immigrants deported from the United States and representing 0.1 percent of the number of visas issued.144 Based on the available evidence, less than 1 percent of illegal immigrants who overstayed visas were H‑2B workers.145 These figures indicate the high value that legal guest workers place on the opportunity for future legal employment. Elvio Miranda from Mexico explained in 2015 that he became a guest worker because, he said, “I don’t want to have trouble with migration [agents].”146

Indeed, nearly all H‑2B workers attempt to return legally year after year, and between 2009 and 2013, about half were successful during that period of waning demand for H‑2B labor.147 In 2007, when Congress exempted returning workers from the visa cap, the program doubled in size.148 Additionally, USCIS assumes that about half of these H‑2B workers manage to find secondary employers to enable them to extend their status for at least a second year, and about a quarter are able to stay for the maximum of three years.149 The frequency of returning workers indicates that whatever H‑2B’s constraints, foreign workers prefer H‑2B jobs to jobs in their home countries or to illegal status.150

This pattern of returning undermines claims that most guest workers face severe abuse. Although abuses of workers have happened, they are not common.151 Polaris, a group dedicated to combating human trafficking, received 248 complaints to its human trafficking hotline from H‑2B visa holders from 2015 to 2017—about 0.1 percent of visas issued.152 These are tragic cases, but as David Medina of Polaris told The Guardian, H‑2 workers’ “biggest fear is to lose that visa.”153

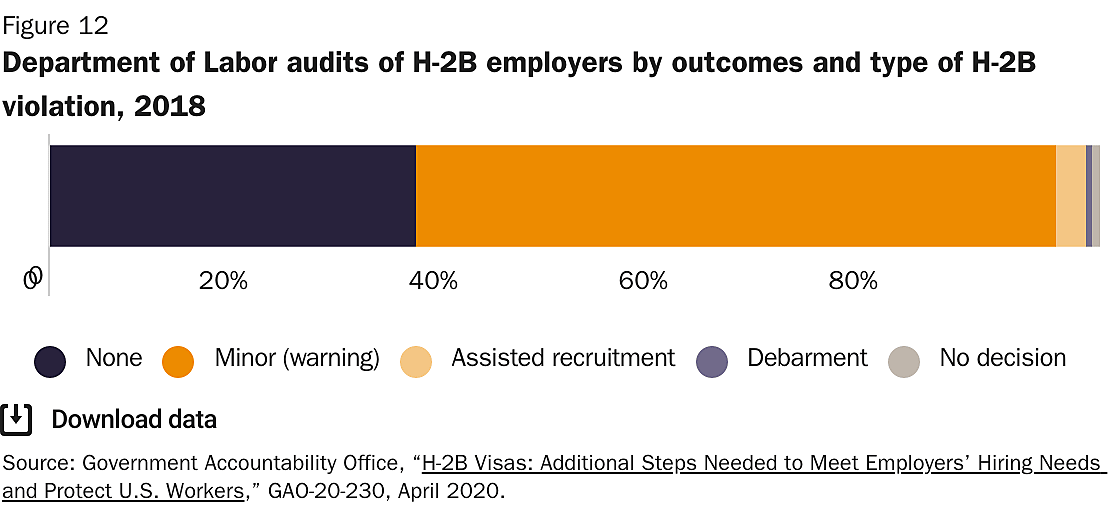

Severe cases of abuse are rare but are often conflated with very common technical violations of the copious and complex H‑2B rules. For instance, DOL’s Office of Foreign Labor Certification audited a random sample of about 7 percent of H‑2B employers in 2018 and found violations in about two-thirds of the cases (Figure 12), but 95 percent of those violations warranted no more action than a warning letter. The GAO reviewed those violations and described them as minor, explaining that “several warning letters noted violations related to the period of employment of H‑2B workers, such as failing to notify OFLC when H‑2B workers left their jobs earlier than planned.”154

The OFLC may require employers to undergo assisted recruitment where it monitors and directs additional recruitment of U.S. workers, or it may debar them from participation in the H‑2B program for any period up to five years if it determines that the employer willfully misrepresented material facts or substantially failed to comply with H‑2B rules. The agency handed down this penalty just eight times from 2018 to 2020, all for failure to provide records in response to an audit request.155 This could demonstrate that the employer failed to keep records, had something to hide, lost interest in the H‑2B program, or that the employer is bankrupt or no longer exists.

Separate from OFLC, DOL’s Wage and Hour Division (WHD) has independent and unfettered authority to conduct investigations of employers for violations of the H‑2B rules.156 The WHD does publish how often its investigations find no violations, but it did turned up 11,841 violations of H‑2B program rules that occurred from 2010 to 2019, but the agency rarely considered them to be very serious and imposed average fines of $637 per violation—95 percent below the maximum of $12,919 available to be imposed under DOL regulations.157 From 2018 to 2020, WHD debarred just nine employers from the H‑2B program for serious violations.158 Figure 13 compares the number of participating H‑2B employers to the number of cases with violations and total debarments (OFLC or WHD) per year since 2010. Debarments are barely visible because severe violations are so rare.

The WHD has also required H‑2B employers to pay a total of $8.5 million in backpay to U.S. and H‑2B workers from 2010 to 2019—about 10 cents for every job requested under the program.159 The H‑2B program requires high levels of oversight by supervisors to prevent these mundane but costly violations. The agency fails to systematically explain the reasons for every underpayment, but its press releases (relating only to what it considers its most serious violators) show that employers sometimes fail to pay workers for time spent commuting to jobs and unloading materials before they clock in, as well as not paying for meal breaks without verifying that workers actually took their full break.160

Another employer violation is allowing workers—either U.S. or H‑2B—to perform job tasks not included in the job order or temporary labor certification. For instance, housekeepers become “front desk personnel” if they greet guests and help them book in.161 “Desk attendants” at a bakery become bakers if they put bread into an oven.162 If an employer fails to report a worker absent from the job to DOL or DHS—a common reason for an OFLC audit warning letter—the employer must still pay the worker for the time he should have worked, even if the worker left on his own.163 Employers can even be deemed to violate the wage rules if they overpay workers for performing work in job categories that have a lower pay rate than the job listed on the job order.164

Technically, employers can obtain prevailing wage determinations for multiple occupational categories, thus allowing a worker to fill multiple roles and receive wages accordingly, but DOL makes this extremely difficult because workers must work in one category at a time.164 Similarly, WHD can fine employers for letting employees work outside the area of normal commuting distance of the jobsite (a vaguely defined locale). Again, this penalty becomes more likely because DOL generally prohibits submitting a labor certification for workers in jobs in multiple areas.166

These mistakes are sometimes portrayed as malicious abuse of “captive” guest workers because H‑2B workers lack the full rights of U.S. citizens. But not only do many of the violations above relate to the treatment of U.S. workers, WHD commonly finds that H‑2B violations occur because the employer treated the H‑2B workers better than U.S. workers. Because the H‑2B program mandates inflated wage rates and other benefits, some employers mistakenly hire U.S. workers at the market wage but then pay their H‑2B workers the higher rate. Employers may also choose to provide H‑2B workers housing if they cannot find anything right away, but this also violates H‑2B rules if they failed to mention it in the job order.167

The DOL and DHS have also enacted rules that better protect foreign workers against actual abuse.168 Employers must disclose the names of foreign labor recruiters that they used, allowing the agencies to check them against the names of known violators. Employers now provide copies of the job order with all benefits, wages, and other program requirements in the employees’ native language before the visa is issued, so workers know what they are agreeing to.169

In addition, consulates often provide workers with briefings about their rights and brochures that explain how to assert their rights and file complaints.170 The prospective employer must also post a DOL poster, printed in the workers’ native language, in a conspicuous location at the jobsite that contains employee rights and phone numbers where they can call to file confidential complaints.171 Employers must provide detailed wage statements to workers every other week, and may not retaliate against workers for complaints, union organizing, or legal consultation.172 If they do lay workers off for any reason, they must pay for their trips home.173

Workers who feel they need legal advice may use Legal Services Corporation (a private entity with federal funding) to receive “brief advice and consultation” by phone, email, or online.174 LSC can also fully represent H‑2B forestry workers and any H‑2B trafficking victim without charge.175 Abused H‑2B workers may also qualify for a T visa for trafficking victims, allowing them to leave their employers and obtain permanent status in the United States if they cooperate with law enforcement.176 Any H‑2B worker who is the victim of a crime may also qualify for a U visa for crime victims who cooperate with law enforcement—again, with the prospect of permanent residence.177 USCIS could better protect H‑2B workers from trafficking or employer abuses by not canceling the status of H‑2B workers when they leave their initial employers and giving them a period to search for a new H‑2B job.178 DOL could support this policy by expediting or eliminating the certification process for H‑2B workers who are already inside the United States, so that when the worker finds a new employer it takes less time to complete the hiring process.

The most common situation that can lead to abuse is when workers pay a fee to a recruiter so that they will be referred to the H‑2B employer for the job. Workers may then come to the United States and not like the job but be so in debt that they have trouble quitting. The rules explicitly prohibit employers from charging fees for the position, and they must contractually prohibit any third parties from doing so.179 Consular officers now ask all H‑2B visa applicants if they paid anything for the job.180 If they did, employers must repay the fees, even if they had no knowledge of the arrangement. While these rules help, it is important to understand that workers will pay a recruiter for an H‑2B job offer exactly because H‑2B jobs are so limited.181 The more H‑2B hires allowed by law, the less valuable each becomes, reducing the leverage of middlemen by giving workers more options to seek legal work in the United States.

U.S. Workers and the H‑2B Program

While regulations require that employers offer all H‑2B jobs to U.S. workers before they can hire H‑2B workers, U.S. workers rarely respond to those offers, particularly in the top H‑2B job categories in the top industries. Many U.S. workers do perform the same types of jobs as H‑2B workers (see Table 1 above), but employers only enter the expensive H‑2B process when they are confident that they have exhausted the local supply of workers. Table 3 shows the number of jobs requested and certified as unfilled by U.S. workers in fiscal year 2020. Overall, 93 percent of H‑2B jobs requested were certified. In six of the top seven occupational categories in the top industries, 96 percent or more of H‑2B jobs requested were certified.182

Employers have turned to the H‑2B program in greater numbers since the 1990s because more U.S. workers are looking for permanent, year-round positions with better pay and working conditions. When U.S. workers are unemployed, they may also have access to government benefits such as unemployment insurance, which helps support them until they find a job that they want. The two most important long-term trends that may have led U.S. workers away from H‑2B jobs are the increasing share of U.S. workers with high school and college degrees and, relatedly, the decreasing share of young people seeking summer employment — specifically men — who had previously often worked summer jobs like landscaping. The labor force participation rate for U.S. teens declined from 59 percent in the summer of 1989 to 35 percent in the summer of 2019.183 At the same time, the share of Americans who have attended at least some college increased from 38 percent to 62 percent, enabling them to find other jobs.184

Fortunately, when employers do meet their temporary needs with H‑2B workers, demand increases for U.S. workers in other, often year-round, positions because H‑2B workers increase firms’ productivity. The GAO found that businesses that received all their requested H‑2B workers reported more revenue than those that did not.185 This enables those companies to support U.S. workers in other roles. By contrast, Mike Leman explained that the H‑2B visa cap cost his company, Singing Hills Landscape in Colorado, a 25 percent sales drop.186 Lehman noted that “We were unable to support the planned hiring of an account manager, a project manager, a CFO [Chief Financial Officer] … and a landscape designer — nearly $300,000 in additional payroll.” Over the last two decades, landscaping companies have hired about one landscaping supervisor for every eight or nine workers. The H‑2B program brought in about 25,000 landscaping workers in 2019, creating demand for about 3,000 supervisors — hardly any of whom come in as H‑2B workers.187

In fact, the number of landscaping supervisory positions increased by 13 percent, or 12,250, from May 1999 to May 2019, as the H‑2B program expanded, but it was even higher in 2007 when the number of H‑2B workers peaked. Figure 14 shows how the expansion of the H‑2B share of landscaping jobs — as a result of more jobs being requested — is generally correlated with growth in employment for supervisors of landscaping workers. “When we can’t get those [H‑2B] workers, we actually have to decline jobs,” John McMahon, the CEO of the Associated Landscape Contractors of Colorado, said in 2020 after employers immediately filled the cap. “In this economic environment, we actually have to turn down millions of dollars of projects that are out there.”188

The increased production that H‑2B workers permit also raises demand for U.S. workers elsewhere because more productive companies purchase more materials and supplies. According to the GAO, “employers that did not receive all requested H‑2B visas under the standard cap more frequently reported declines in purchases of goods and services than employers who received visas in 2018.”189 Mike Baker, the owner of Baker Landscape and Irrigation in New York, explained that when he failed to receive H‑2B workers because of the cap in 2019, he reduced services and turned away at least $150,000 in contracts, which meant that he spent $125,000 less on materials than the prior year, and he abandoned his plan to buy a truck. “The Ford dealer got less money,” Baker said.190 H‑2B workers also spend a significant portion of their wages in the United States for housing and food, creating further demand for jobs in those sectors.

When jobs get filled quickly, the cycle of filling jobs and creating demand for other jobs speeds up. Unemployed U.S. workers might take years to move to seasonal jobs in — to take a common H‑2B example — a resort town. But when H‑2B workers fill them immediately, that creates demand for an array of other jobs elsewhere and the overall job market starts to improve. Research has found that by being faster to move to open jobs, foreign workers — including H‑2B workers — “grease the wheels of the labor market,” raising the wages of U.S. workers by billions of dollars annually by increasing demand for jobs where U.S. workers live.191 In the same vein, the National Academy of Sciences has noted that “immigration can lower native unemployment” because the “entry of new workers through migration increases the likelihood of filling a vacant position quickly and thus reduces the net cost of posting new offers.”192

By taking temporary, and often remote, jobs, H‑2B workers also allow U.S. workers to specialize in permanent jobs that are closer to home. Economic research has shown that low-skilled immigration has caused Americans without a high school degree or only a high school degree to shift to “interactive and language-intensive tasks” that are less physically demanding and that foreign workers with limited English-language skills cannot as easily perform.193 Similar research has demonstrated that this shift has led Americans to work in safer jobs, resulting in fewer workplace injuries.194 Forestry, for example, is one of the most dangerous jobs in the United States, so by filling nearly all H‑2B forestry jobs and creating demand for other jobs for Americans, H‑2B workers make the workplace safer for Americans.195

Streamlining the H‑2B Program

The H‑2B program exists to prevent temporary jobs from going unfilled when U.S. workers don’t take them. The current rules mainly focus on making these jobs attractive to American workers — such as by mandating higher wages and benefits — but do relatively little to ensure that employers can efficiently fill the positions that U.S. workers reject. The H‑2B visa cap and its rules limit the program’s potential as a powerful economic engine and an alternative to illegal employment. Many employers cannot use the program for three reasons: the cap is too low, the costs are too high, and the process is too long and complex. This section details reforms intended to rectify these shortcomings.

Fixing the H‑2B cap

The most pressing problem facing the H‑2B program is that demand for workers far exceeds the annual visa cap of 66,000 — a number that Congress invented three decades ago with almost zero public debate in the Immigration Act of 1990.196 The H‑2B cap is unjustifiable. There are two ways to execute a protectionist visa policy: one is a cap, and the other is mandated recruitment of U.S. workers. The H‑2A program for agricultural workers is uncapped because farmers must first recruit U.S. workers. The H‑1B program for skilled workers has a cap because there is no recruitment mandate. But the H‑2B program inexplicably has both. Employers must recruit U.S. workers, and even if U.S. workers reject the jobs, the law can still require the positions to go unfilled, thus harming employers and U.S. workers in complementary employment.

Congress should uncap the H‑2B program, but in lieu of congressional action, the administration can adopt three rule changes to mitigate the cap’s perverse effects. First, DOL should allow employers with recurring temporary positions to recruit workers who will commit to return year-after-year, certifying the temporary recurring job for at least three years at a time.197 As is the case now, the State Department should grant a visa valid for the certification length,198 and CBP should then grant a right to H‑2B status valid for the duration of the petition (three years).199 Because the cap only applies to new visa issuances or grants of status pursuant to a new petition, three-year grants would greatly ease the effect of the cap.200 During the time between seasons, H‑2B workers could return home or find other H‑2B jobs.

Employers already treat these returning workers as existing employees coming back to their positions after a couple months away.201 Indeed, when employers start the H‑2B prevailing wage determination process, the future returning workers are almost always still working that job. If the agencies adopted the employers’ view, the job orders could perhaps attract more Americans by notifying them of the jobs’ recurring nature, while also streamlining the process for H‑2B employers and workers if Americans rejected the multiyear offer.

Second, USCIS should remove the requirement that currently employed H‑2B workers leave the country for 90 days after three years.202 This requirement forces economically pointless turnover on employers and imposes unnecessary administrative burdens on the government. It can create the potential for more visa overstays and requires vetting a whole new crop of untested foreign workers — a waste of resources for everyone involved. Other categories of temporary workers are not subject to this requirement — such as international students and O‑1 visa holders for workers with “extraordinary ability” — and USCIS has already permitted extensions beyond the three-year limit during the COVID-19 pandemic for employees who are considered to be essential to the U.S. food supply.203 Extending this policy to all industries would provide much-needed visa cap relief.

Third, USCIS should authorize spouses and older minor children of H‑2B workers entering on H‑4 visas to work, filling any H‑2B job that the cap would otherwise cause to go unfilled. USCIS has already used its authority to grant employment authorization documents for certain H‑4 spouses of H‑1B workers, and it can use this power to permit employment by family members of H‑2B workers and make sure that the H‑2B program is fulfilling its economic purpose.204

Improving H‑2B wages

The H‑2B rules also inflate the prevailing wage higher than the wages for a majority of similar U.S. workers, which is unfair to employers who are seeking to hire foreign workers legally. The artificially high wage requirement actually encourages employers to hire illegal workers with fraudulent or borrowed documents rather than follow the process that Congress established to solve labor shortfalls.

The easiest way to correct this problem would be to permit the use of a job category’s median wage (the exact midpoint of all wages) rather than the average wage (which is almost always skewed higher as a result of outliers at the top end of the wage distribution) as the prevailing wage. In 2015, DOL justified using the average wage because it “provides equal weight to the wage rate received by each worker in the occupation across the wage spectrum.”205 Yet this is precisely why it should not be used. A single atypical wage can skew the average, particularly in areas with few observations. For this reason, the Bureau of Labor Statistics reports the median wage as the “usual weekly earnings of wage and salary workers,” not the average.206

A more significant reform would be for DOL to stop requiring the average wage for an entire job category and return to using skill levels to determine wages. The agency’s preferred wage source (the Occupational Employment Statistics survey) does not record skills directly (such as by asking about workers’ experience, training, education, etc.), but DOL had previously overcome this shortcoming by mathematically creating four OES wage levels. The DOL reasonably assumed that lower wages would reflect lower skills within the same jobs in the same area, so in 1998, it had the Bureau of Labor Statistics take the one-third of workers with the lowest wages in the job category and average those wages to manufacture an “entry level” wage at the lower end of the wage distribution. It then took the top two-thirds of wage earners and averaged their wages to create a “fully competent,” or supervisory, wage level at the top of the distribution. In 2005, it created two intermediary levels that are equally distributed between the top and bottom wages.207

But in 2013 and then in 2015, DOL rejected this approach in two rules by denying the existence of “significant skill-based wage differences in the occupations that predominate in the H‑2B program.”208 Inconsistently, the agency continued to create OES wage levels for permanent jobs in the exact same job categories as those included in the H‑2B program under the immigrant visa program.209

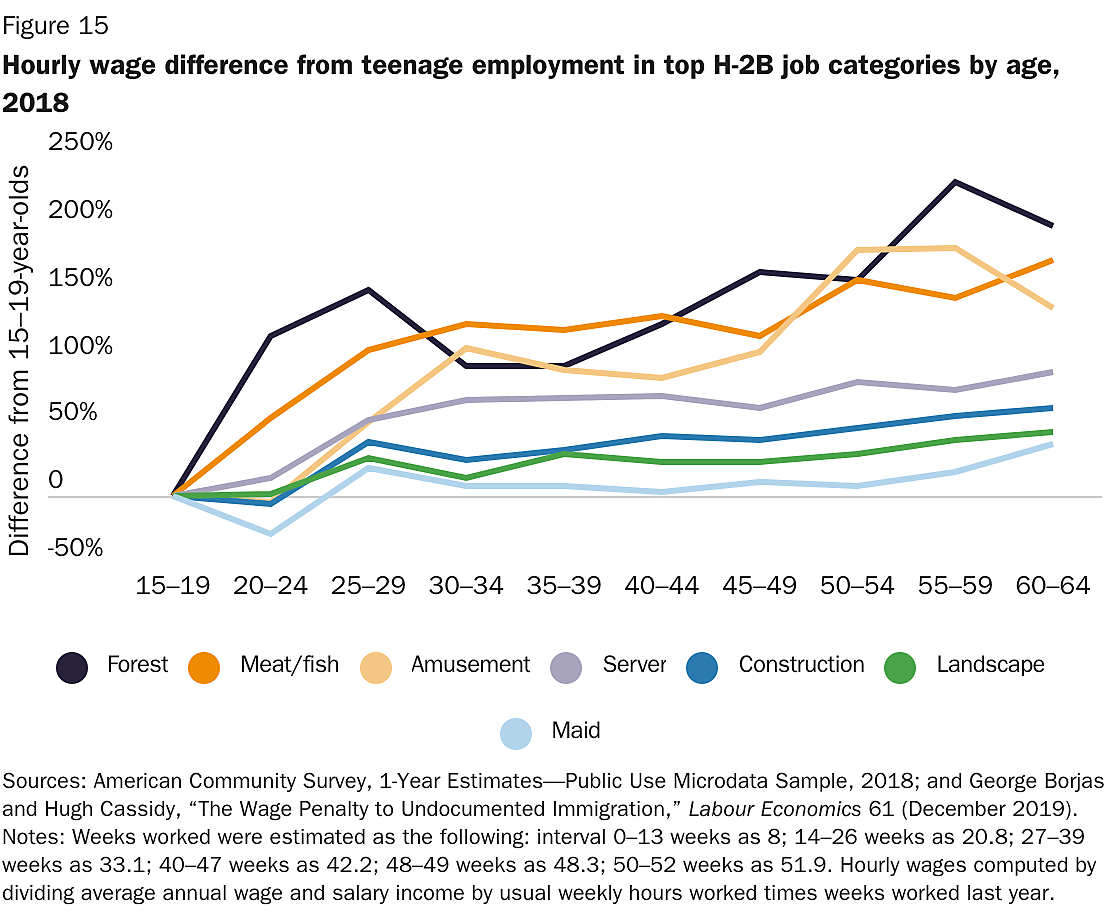

In any case, DOL is wrong that no skill-based wage differences exist in H‑2B jobs. Figure 15 uses data from the Census Bureau’s American Community Survey — which, unlike the OES, collects responses from individuals in households rather than businesses — to show that wages generally rise with age in all the top H‑2B jobs. While maids saw minimal wage growth, other workers aged 35 to 39 averaged higher wages than teenage workers in their job categories: from 32 percent for landscapers to 123 percent for meat and seafood processors. In absolute terms, that is between $3.22 and $9.48 in higher wages per hour. Given that these are the exact same jobs but with employees of different ages, these increases mostly reflect the increasing skills of workers over time.210 Greater experience leads to better skills, which in turn leads to greater productivity — and that makes the worker more valuable to the company. The DOL should return to its earlier skills-based wage structure for jobs.

H‑2B wages should only apply to American workers who are hired directly as a result of the posted job offer as part of the TLC process. The wages, benefits, and regulations should not apply to existing workers or other hires. The corresponding employment rule that extends the regulations to all similar U.S. workers makes it too expensive and risky to go through the H‑2B process for a marginal position that could be left unfilled — even if it means worse service or lower productivity — because the H‑2B costs are spread to all similar employees. Congress has repeatedly defunded enforcement of this rule each year since its introduction in 2015, but DOL has maintained it and threatens to enforce the rule against employers who violated it during the period when enforcement was defunded.211 Congress or DOL should simply rescind the rule to provide certainty for U.S. employers.

Finally, the prevailing wage determination should not apply to H‑2B workers at all because its only stated purpose is to prop up the wages of Americans. Foreign workers would only take H‑2B jobs if the wage offered is higher than their wages at home, and a higher wage would result in fewer hires, thus harming foreign workers overall. If employers recruit at the prevailing wage and cannot find U.S. workers to fill the positions, they should be able to hire as many H‑2B workers as they want at the market wage. After all, if American workers refused the job at the higher wage, they would reject it at a lower wage as well. This change would allow the employers to potentially hire twice as many H‑2B workers, thus increasing the productivity of their companies and raising the demand for U.S. workers in complementary jobs.

Streamlining the process

As Figure 2 shows, the H‑2B application process winds its way through a bureaucratic labyrinth with substantive reviews by two DOL subagencies, the State Workforce Agency, USCIS, and the State Department, over at least five months with two potential backend review processes. First, DOL should harmonize the H‑2B prevailing wage determination process with the H‑1B process for high skilled workers, under which H‑1B employers can either obtain a prevailing wage determination or simply choose to look up the relevant wage for the job and risk the penalties if they use the wrong rate.212 If DOL refuses to trust H‑2B employers to the same extent that it trusts H‑1B employers, then it should allow employers that have received prior PWDs based on the same job description to look up the relevant rate.

Second, DOL should create a single filing platform or portal for submitting a temporary labor certification, State Workforce Agency job order, and USCIS petition with the relevant portions reviewed only once by each agency. The USCIS should not duplicate the labor department’s efforts by making a separate determination of whether a job is temporary by using different evidence. In this proposed model, USCIS would have no substantive information to review in the petition portion of the single filing platform if the employer did not request specific workers.213 Instead, it would automatically approve the petition. The USCIS could adopt this automatic approval concept even without a single filing platform. If employers tell DOL that they are not seeking named workers, DOL could forward the temporary labor certification to USCIS, which could immediately approve the petition without additional employer actions.214

Third, DOL should restore the streamlined TLC process that it used between 2009 and 2015, which allowed employers to conduct the recruitment prior to filing a TLC, effectively moving the application (Figure 2, Step 3) to when the initial recruitment report is filed (Step 5).215 In addition, when employers filed the TLC, they did not need to submit — and DOL did not need to review — all the underlying evidence of recruitment and temporary need, thus eliminating the recruitment report filing (Step 5) and allowing for a much shorter filing timeframe. Instead, employers attested that they had a temporary need and recruited U.S. workers. Rather than conducting a detailed certification review, DOL had the authority (for the first time) to conduct post-certification audits and issue fines to verify H‑2B attestations. The DOL justified this shift to using resources at the backend of the process on the grounds that audits provide a better assessment of program compliance than the temporary labor certification.216

In 2015, DOL reversed the streamlining changes and required an even longer period of recruitment after filing a TLC (an increase from 10 days to between 40 and 70 days), stating that these changes would reduce program violations and encourage more U.S. workers to respond to job orders. Both predictions turned out to be incorrect. In 2018, DOL’s random audits uncovered a higher percentage of employers with violations than in 2010 and 2011, when DOL used the attestation process.217 Moreover, as Figure 16 shows, the shifts from certification to attestation and back made no change in the percentage of jobs that DOL certifies as unfilled by U.S. workers, implying that it found that U.S. workers were not more likely to apply for H‑2B jobs. Meanwhile, the time between filing and final adjudication jumped from 18 days in 2014 to 47 days in 2019.

Conclusion

The H‑2B program has more than 175 bureaucratically complex rules that prevent employers from accessing legal workers. H‑2B mandated wages have increased at twice the rate of all wages since 2011, but still, few Americans are willing to take these temporary, often tough jobs. The H‑2B program expanded rapidly in the early 2000s as fewer illegal workers crossed the border, which caused illegal immigration from Mexico to decline even further. Unfortunately, the low H‑2B cap still prevents even employers willing to engage in this lengthy legal process from filling open positions.

The H‑2B program benefits American employers who cannot find willing U.S. workers at the prevailing wage and increases demand for other jobs that U.S. workers are more willing to fill. To increase these benefits, policymakers should streamline the H‑2B application process, base wages on skill level, and raise or eliminate the H‑2B cap to accommodate U.S. employers’ proven needs. It should issue visas and status that last a minimum of three years to avoid workers having to reapply every year, and it should allow renewals beyond three years if the workers maintain employment. It can also craft rules to allow foreign workers to easily leave and change employers throughout their three-year period to further prevent abuses.

Appendix

Citation

Bier, David J. “H‑2B Visas: The Complex Process for Nonagricultural Employers to Hire Guest Workers,” Policy Analysis no. 910, Cato Institute, Washington, DC, February 16, 2021. https://doi.org/10.36009/PA.910.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.