Federal, state, and local governments seek to assist poor households financially using transfers, minimum wage laws, and subsidies for important goods and services. This “income-based” approach to alleviating poverty aims both to raise household incomes directly and to shift the cost of items, such as food, housing, or health care, to taxpayers. Most contemporary ideas to help the poor sit firmly within this paradigm.

A “cost-based” approach would instead reform existing government interventions that raise living costs for the poor. Shelter, food, transport, and apparel and footwear alone account for 59 percent of spending by the average household in the bottom 20 percent of the income distribution, and government policies raise prices in all those sectors. Local land-use and zoning regulations constrain housing supply, which raises housing costs and deters labor mobility. State child-care staffing regulations reduce the number of infant centers in poor areas, increasing prices and reducing the payoff to work. The federal sugar program, milk-marketing orders, and ethanol mandates make grocery shopping more expensive. Federal fuel-standard regulations and state-level automobile dealership laws increase the cost of driving. Protectionist tariffs raise clothing and footwear prices, and state occupational licensing creates barriers to entry that raise the price of many services, from hair braiding to dentistry, while reducing labor-market opportunities.

Using cautious assumptions, I estimate that these interventions, combined, cost typical low-income households between $830 and $3,500 per year directly through higher prices. Pro-market reforms in these areas could significantly reduce living costs for the poor, while also improving labor mobility and job matching. With the federal budget deficit growing and demands for radical labor-market policies proliferating, such an agenda would represent an economically efficient means of improving the well-being of the poor without requiring more government spending or intervention.

Introduction

American government at the federal, state, and local levels delivers policies intended to help households on low incomes. Total annual expenditure on U.S. anti-poverty programs is estimated to exceed $1 trillion per year.1 Governments redistribute income, provide benefits-in-kind, and subsidize the provision of certain services on the basis of need. They also pass mandates and regulations, such as minimum wage laws or limits on drug prices.

Though liberals and conservatives have different theories about the causes of poverty, the dominant paradigm for alleviating it rests on “income-based” approaches.2 Policies attempt to raise the incomes of the poor directly through cash transfers, tax breaks, and minimum wage laws or to raise the poor’s disposable income indirectly by shifting expenditure on goods and services to taxpayers through programs such as Medicaid.

This income-based approach underpins contemporary policy ideas. Senate Democrats advocate a $15 per hour federal minimum wage.3 Their 2016 presidential candidates, Hillary Clinton and Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-VT), proposed new universal preschool and child-care programs.4 More recently, Senator Sanders backed a federal jobs guarantee designed to ensure a labor market wage floor.5

Universal basic income and negative income taxes, regularly touted as more efficient and freedom-enhancing means of income redistribution, nevertheless remain firmly in the income-based school of poverty alleviation.6 “Reform conservatives” have likewise long advocated for increasing the generosity of the earned income and child tax credits.7 Even conservatives who want to see less generous redistributive programs agree that income growth is important to reduce poverty.8 They want to improve incentives and broaden economic growth so that the poor can earn their own way out of poverty.

Income is important to well-being. But focusing on earnings and transfers overlooks another way to help the less fortunate: reforming existing government policies that raise the prices of basic goods and services and thereby hurt the poor through higher living costs.

In markets where low-income households spend significant amounts — on housing, childcare, food, transport, clothing, and services regulated through occupational licensing — interventions designed to achieve other objectives restrict supply and in turn raise prices. Since these goods are relative necessities, these interventions impose disproportionate burdens on the poor. They are left with less disposable income, heightening calls for further taxpayer-funded redistribution or government interventions to counteract the effects of the policy.

This paper sets out nine policy areas across all levels of government that, combined, directly raise spending for typical households in the bottom 20 percent of the income distribution by anywhere from $830 to $3,500 per year. This list is hardly comprehensive; to avoid subjective judgments about the effect on prices relative to other objectives, this analysis focuses exclusively on anti-competitive interventions and regulations that both raise prices and reduce overall economic efficiency.9 A “cost-based” approach to poverty alleviation through reform in these areas could therefore provide a significant financial boost to low-income households.

For too long, scholars on the left and right have thought about alleviating poverty as something that should occur after market-based activity has taken place. But removing misguided regulatory interventions would reduce poverty while expanding markets, simultaneously reducing the cost of living for low-income families and growing the economy. Even on cautious assumptions, the indicative numbers outlined here suggest that reform in these areas could be a powerful tool against poverty and should take precedence over new programs, regulations, and interventions.

Why a pro-market agenda for those on low incomes?

The dominant “income-based” approach to helping the poor can directly alleviate financial hardship. Accounting for federal cash benefits, tax credits, and benefits-in-kind, the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities estimates that the U.S. poverty rate fell from 18.9 to 10.9 percent between 1964 and 2011, as redistributive spending increased substantially.10 Bruce Meyer and Derek Wu recently concluded that five of the six programs they examined — Social Security, Supplemental Security Income, Temporary Assistance for Needy Families, housing assistance, and food stamps — help reduce measured poverty substantially.11

Of course, these types of analyses fail to model a counterfactual world in which extensive government redistribution does not exist. With lower tax burdens, civil society institutions and charities would surely offer more generous support for those in need. Without extensive welfare and entitlement programs, worker and household behavior in the long run would be very different. The real net effect of government redistribution on the financial position of poor households is uncertain and theoretically ambiguous.

But it would be unsurprising if government transfers and benefits-in-kind raised disposable incomes for some recipients above what they could obtain from market-based activity and civil society assistance, particularly in the short run. Minimum wage hikes likewise raise incomes for workers from poor households with low pay rates who are lucky enough to keep their jobs and hours (though minimum wages are not a well-targeted poverty reduction tool generally).12

Yet, even accepting that the “income-based” approach raises income levels for many today does not mean that further expanding this approach is the best way to help the poor going forward. Consider the following:

- Diminishing returns. Economists Bruce Meyer and James Sullivan have estimated that less than one-third of the reduction in the after-tax income poverty rate seen between 1960 and 2010 took place after 1972, with no progress at all after 2000, despite massive spending increases.13 This is consistent with redistribution exhibiting diminishing returns as a poverty- reduction tool.

- The fiscal environment. The federal deficit is projected to rise to 5.1 percent of GDP by 2022.14 This adds to an unsustainable long-term federal debt outlook, driven primarily by projected increases in Social Security and Medicare spending as the population ages.15 Increasing spending to further reduce poverty would, absent tax increases, worsen the structural deficit and make an unsustainable fiscal outlook worse.

- Negative consequences of more redistribution. Substantial additional redistribution would eventually require raising taxes. This would depress the level of GDP by raising marginal tax rates, at a time when future potential economic growth rates are already expected to be low.16 The means-tested nature of redistributive transfers means that increasing their generosity also results in either steeper withdrawal rates for recipients or more people being drawn into the system. The higher effective marginal tax rates both these outcomes generate would further erode work incentives.

- Negative consequences of minimum wage hikes. Set conservatively, minimum wages have modest effects on overall employment, with the burden falling heavily on those with low levels of labor market attachment (such as teenagers).17 Recent evidence from Seattle suggests much larger disemployment effects occur when minimum wages are increased from an already high level.18 Huge minimum wage hikes would therefore bring significant risks at a time when the labor market is looking increasingly healthy, with the unemployment rate at just 4 percent.19

- Redistribution is vulnerable to changing sentiment. Attitudes to welfare can be volatile, and preferences for redistribution replaced by narratives about “moochers” and “welfare queens.” The experience of other countries suggests politicians find it easier to cut working-age welfare expenditure in times of fiscal crisis than other major spending categories.20

You do not have to believe existing anti-poverty programs have failed in order to acknowledge these unintended consequences, diminishing returns, and need for taxpayer goodwill.

A “cost-based” agenda focused on removing damaging government interventions, in contrast, would not require additional government spending. By making essential goods cheaper, such a policy may reduce spending levels by lowering the political demands for redistributive transfers. If delivered through reforms to policies that currently undermine economic efficiency, it would also raise GDP and market-obtained incomes without the risks of unemployment from minimum wage hikes or the need for higher marginal tax rates. A beneficial side effect might also be restored faith in the market economy to deliver affordable goods and services, resulting in a political environment more conducive to pro-growth reforms in other sectors.

None of this means a pro-market cost-of-living agenda would be easy to deliver. Powerful supporters of existing interventions will resist such change. Zoning and land-use planning reforms often run counter to the interests of existing homeowners and will be opposed by coalitions of NIMBYs.21 Professionals with occupational licenses will argue that licensing improves service quality. Industries that benefit from extensive government protection, such as dairy and sugar farmers, textiles producers, and automobile dealerships, will petition state and federal politicians to protect their own interests. The bureaucracies that implement these programs and regulations also have a vested interest in ensuring their continuation.

Yet, these interventions currently come at a high cost to the poor. A pro-market “cost-based” reform agenda to reduce prices of essential goods and services should be considered an important tool in an effective and enduring “first do no harm” approach to reducing poverty.

Where might a pro-market agenda have a big effect?

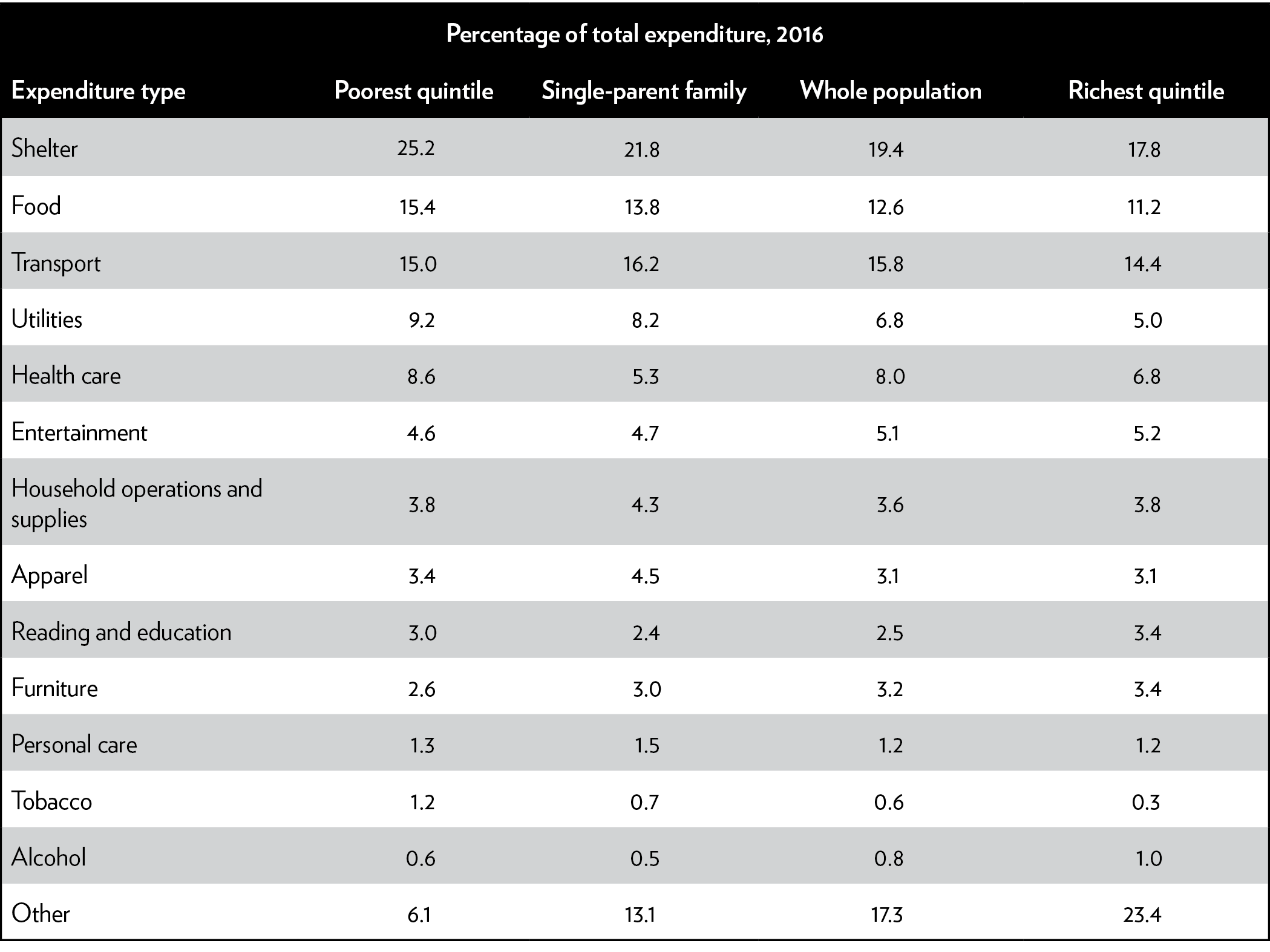

The Bureau of Labor Statistics Consumer Expenditure Survey shows the average amount spent by households across the income distribution on categories of goods and services. Table 1 shows households in the bottom 20 percent of the income distribution tend to spend a much higher proportion than the rest of the population on “essential” goods and services. Shelter, food, transport, and apparel together account for 59 percent of the $25,318 spent by the average household in the poorest income quintile, compared with 50.9 percent for the average household across the whole population and 46.5 percent for the average household in the richest quintile.

Table 1: Expenditure by category

Source: Data from Bureau of Labor Statistics, Consumer Expenditure Survey, https://www.bls.gov/cex/tables.htm#avgexp.

This masks substantial differences by household composition and region. The average single-parent family spends proportionately more on apparel than do two-parent families. Households in some major U.S. cities spend much more on shelter. In San Francisco, even the average household apportions as much as 28.7 percent of spending to shelter, and similarly high figures are seen in New York (26.5 percent), Boston (25.2 percent), Los Angeles (24.2 percent), and Miami (24.0 percent).22 Families with young children where both parents are employed face very costly child-care bills too. In Washington, D.C., Child Care Aware estimates an average annual cost of formal infant care of $23,089.23

Without data disaggregated by region, household composition, and income level, one cannot reach firm conclusions about the financial costs of existing policies to individual families. Nevertheless, this high-level analysis shows markets where a meaningful anti-poverty agenda will have the biggest effect. Housing and child-care costs are likely to be particularly significant for those households in major metropolitan cities or with young children.

The remaining analysis highlights current government policies that drive up the cost of housing, childcare, food, transport, apparel and footwear, and services with occupational licensing requirements, and estimates their likely cost to poorer households.24

Shelter

The single largest expenditure for most families is shelter (rent or the cost of owner-occupied housing). It makes up 25.2 percent of total spending for the average household in the poorest quintile, and 21.8 percent for the average single-parent household. Since the poorest quintile includes many older and poorer households with low incomes, spending as a proportion of income is higher still. The Pew Foundation estimates households in the bottom third of the income distribution spent 40 percent of their income on housing in 2014, while renters spent nearly half.25

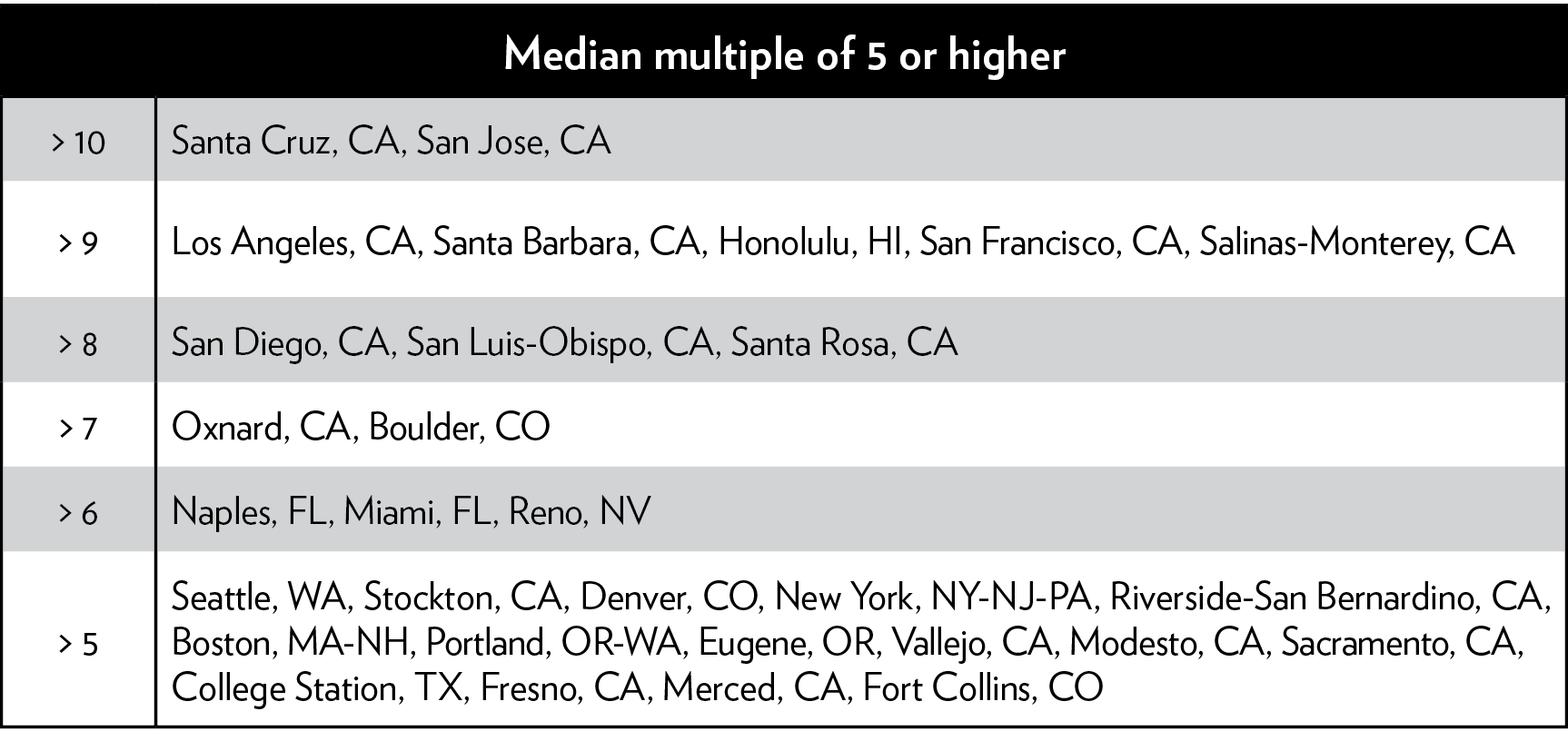

The United States has relatively cheaper housing overall than other major developed English-speaking countries. But prices and rents are extraordinarily high in certain metropolitan areas. Demographia’s median multiple index (median house price divided by median income) is over 9 in Los Angeles and San Francisco, and just below 6 for Seattle and New York (see Table 2).26 Thirty overall housing markets and 13 major metropolitan markets are defined as “severely unaffordable,” meaning they have median multiples of 5.1 or over. But even these are quite broad markets, including suburban areas on the outskirts of cities. The online housing marketplace Zumper estimates that the median one-bedroom rental price in March 2018 was $3,400 per month in San Francisco; $2,900 in New York; $2,450 in San Jose; $2,300 in Boston; and $2,220 in Washington, D.C.27

Table 2: Severely unaffordable housing markets

Source: Demographia.com, 14th Annual Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey, 2018, January 22, 2018, http://demographia.com/dhi.pdf

Note: The median multiple is the result of dividing median house price by median household income.

High housing costs have major consequences for the poor, both in direct financial terms and, indirectly, in terms of labor mobility and job match. They encourage families to live in smaller apartments and condominiums, to commute greater distances to jobs, and can even act as a prohibitive financial barrier to taking up employment opportunities in certain cities.

Regulatory restraints at the local-government level have a significant effect on housing affordability. Land-use planning and zoning laws — including urban growth boundaries, minimum lot sizes, density and height restrictions, and design requirements — raise the costs associated with providing new housing, restricting the potential supply and making it less responsive to changes in demand. The result of the latter is structurally higher prices as incomes rise and the population grows.

Because of the vast, complex, and differentiated nature of regulations across the country, it is difficult to measure and compare the permissiveness toward development across regions, but economists have used two techniques to measure the effects of regulations.

Some estimate an implied “regulatory tax” as the deviation between new house prices and marginal building costs. Using this method, Ed Glaeser, Joseph Gyourko, and Raven Saks estimated that Manhattan condominium prices were 50 percent higher in the early 2000s than under a free development regime.28 For single-family homes across the country, their estimates show regulatory costs much higher in some areas than others — being indistinguishable from zero in cities such as Baltimore and Houston, but as high as 53 percent in the San Francisco Bay Area, 34 percent in Los Angeles, 22 percent in Washington, D.C., and 19 percent in Boston. Work by the Cato Institute’s Vanessa Brown Calder has subsequently found that regulatory burdens have intensified in many areas since the Glaeser et al. article appeared. We would therefore expect these implied regulatory taxes to be higher in many cities today.29

Other economists estimate the effect of land-use regulations on prices and rents econometrically. Results from these studies, again, consistently suggest that tighter regulatory constraints drive higher housing costs. A 1996 paper by Stephen Malpezzi examining metropolitan markets found that increasing regulation by one standard deviation from average lowered construction by 11 percent and raised house prices by 22 percent.30 A more recent assessment found that a similar one-standard-deviation increase reduced construction by a larger 17 percent, with twice the upward effect — 34 percent — on housing prices.31 A study of cities in Florida also found that restricting growth through farm preservation and open-space zoning made housing more expensive, with the most pronounced effects on the price of smaller houses.32

Anti-development regulations have regressive effects. Poorer households are more likely to rent (61 percent of households in the bottom quintile and 66 percent of single-parent households rent, compared with just 38 percent for the population as a whole). An increase in housing costs has unambiguously negative consequences for renters. Poor households also tend to spend relatively more on housing, are more likely to value lower housing costs over improved amenities, and are more susceptible to being locked out of rich, productive cities and the economic opportunities they bring. This can have a big macroeconomic impact. Chang-Tai Hsieh and Enrico Moretti estimate that lowering the level of housing regulation to the median level across all U.S. cities for New York, San Francisco, and San Jose alone would raise long-term U.S. GDP by nearly 9 percent.33

The negative consequences of land-use and zoning laws can also result in policies that exacerbate these regressive effects further. Local rent control laws, for example, are notionally justified as attempts to keep rents affordable, but binding controls deter investment in the rentable stock and encourage existing landlords to convert units to noncontrolled tenure types or to be more discerning about tenants. A recent study on the expansion of rent control in San Francisco in 1994 shows how this hurts the poor.34 Landlords converted some properties to owner-occupied apartments and condos better suited to higher-income families. The overall supply of new housing fell too, increasing market rents by over 5 percent. Rent control both increased the cost of rental accommodation and intensified gentrification.

Federal taxpayers foot the bill for these mistakes, with relatively more housing aid flowing to states with restrictive zoning and land-use rules.35 Treating the symptoms in this way helps entrench unnecessarily restrictive regulations. Subsidies ease the pressure on local governments to address the cause of high housing costs.

How much do existing regulations raise house prices or rents for households in the poorest 20 percent of the income distribution? It depends on where they live. Residents in many rural areas face no real housing cost increases. But estimates of regulatory taxes for major metropolitan areas by Glaeser et al. imply that average annual housing costs in New York are $2,060 more than in a competitive housing market; $3,200 in Boston; $5,230 in Los Angeles; $3,939 in D.C.; and a whopping $11,500 in San Francisco.36

Some degree of regulatory tax in major cities might be appropriate given the externalities associated with new building, not least congestion. In cities such as San Francisco, the income distribution is very different from the national average too, meaning that there are fewer poor people residing in the city who would benefit directly from liberalization (though this is partly the result of high housing costs).37 On the flip side, the Glaeser et al. estimates apply to the housing markets of nearly 20 years ago; since then the regulatory burden has intensified. New York as a whole has an income distribution similar to the overall U.S. population. Even using Glaeser’s older regulatory tax estimate implies that the poorest 20 percent there currently pay $1,044 per year more for shelter than they would under a permissive development regime.38 These calculations would be much higher still for several cities in California.

Calculating an average effect for poor households across the country is difficult. Salim Furth has estimated that the average household’s annual housing costs increase by $1,700 as a result of land-use regulation. This implies housing costs for the poorest fifth are about $1,000 higher than they need be annually, given relative differences in spending on shelter. A similar result arises using Calder’s alternative measure of land-use regulation. Making the assumption that those states with above-average regulatory burdens were able to reduce these to the average of the rest of the country implies annual savings of $1,075 per year for poor households. But given that poorer households are more likely to live in rural areas, those figures may somewhat overestimate the effect.

Nevertheless, the direct cost of land-use planning and zoning regulations on low-income households could reasonably be anywhere between $0 and around $2,000 per year in the long term, depending on location. The broader economic costs are much greater still, given the secondary effect of poorer families finding it more difficult to move to areas with high-paying jobs. For single-parent households the range would be even wider, with regulatory costs up to around $3,500 or more for wealthier single-parent households in California’s most restrictive cities. Land-use and zoning liberalization could, in the long term, reduce housing costs significantly and greatly increase economic opportunities.

Childcare

Childcare is expensive. The average annual cost of infant-center care varies from a low of $5,178 in Mississippi to a high of $23,089 in D.C. (25.7 percent and 114.5 percent of the federal poverty income level, respectively).39 Even accounting for income variance by state, care costs for an infant average 89.1 percent of median single-parent family income in D.C.; 70.9 percent in Massachusetts; and 57.0 percent in New York. Even in cheaper states, these costs average 27.2 percent in Mississippi; 28.9 percent in Louisiana; and 30.0 percent in Alabama.40 For a family with two young children, the cost burden can be extremely heavy.

State governments control child-care policy, and variation exists in terms of assistance for poorer families.41 Overall, though, U.S. out-of-pocket costs for a typical single parent working full time are higher than any other OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) country.42 Not only are U.S. market prices higher than average, but parents receive less in the way of taxpayer subsidies.

These high prices can have negative consequences for poor families. Poorer single mothers are sensitive to child-care prices when making decisions about entering the labor market.43 Mothers from poorer families, or those with low levels of educational attainment, are least likely to be working.44 Previous data from the U.S. Census Bureau also show that poorer families are price sensitive in the type of care they choose. Children with employed mothers living in poverty are more than twice as likely to be cared for by an unlicensed relative.45

More mothers of young children are choosing to work (in 1975, 28.3 percent of mothers with children under the age of 3 and 33.2 percent of mothers with children under the age of 6 were employed, compared with 59.4 and 61.5 percent, respectively, in 2016), making high child-care costs a salient political issue. Pressure is building for governments to help poor families with these costs.46

There are good reasons why prices for formal childcare are high. It is a labor-intensive personalized service entailing the care of children, whom parents tend to value highly. A strong correlation between areas with high child-care costs and costs as a proportion of income suggests childcare is strongly “income-elastic” too — richer people want to spend relatively more on it.

Yet economic evidence suggests child-care prices are also driven higher by state-level regulations. Input requirements designed to improve care “quality,” including staff-qualification requirements and minimum staff-to-child ratios, significantly raise prices, with little evidence that they achieve other objectives.

These regulations are particularly regressive but get justified on “market failure” grounds. Parents are supposedly unable to observe accurately the quality of care in the sector, or underestimate the social benefits arising from “high-quality” childcare, necessitating minimum quality standards.

But these theoretical arguments are not robust and ignore the market context.47 Most importantly, the regulations cannot ensure quality directly, not least because the true child-care market includes much more than formal infant-center care. If regulations affect prices, they can be the cause of substitution away from formal centers into more informal arrangements, the quality of which varies greatly.

Suppose a new regulation requires an increase in the staff-child ratio or child-care workers to achieve higher qualification levels. The former could increase quality by increasing staff interactions with individual children and the latter by making caregivers better trained to interact with the child in ways that foster development. The combination of the regulations may satisfy some parents that their children will be well cared for, and this “quality assurance” effect may raise overall demand for formal care.

Yet, raising the staff-child ratio has the effect of restricting the revenue-raising potential of each worker or of raising staffing requirements for a given number of children. These increased costs reduce the supply of formal care, thus increasing prices, and could lead parents to choose less costly alternatives. If centers compensate by paying staff lower wages to avoid this, the industry may attract lower-quality workers. Child-care providers likewise may respond to the cost increase arising from higher government certification requirements on caregivers by hiring cheaper, lower-quality support staff or purchasing lower-quality equipment. The effects of both regulations on the quality and use of childcare are therefore theoretically ambiguous.

Empirical work suggests that staff-child ratio regulation increases child-care prices substantially. Diana Thomas and Devon Gorry analyze variation in prices and staff-child ratios across states, estimating that loosening the requirement by one child across all age groups (regulations tend to vary by child age) reduces prices by between 9 and 20 percent.48 This supports an older result from Randal Heeb and Rebecca Kilburn, who found that reducing the number of children per staff member by two would raise the price of childcare by 12 percent.49

The poor suffer disproportionately from these higher prices. Thomas and Gorry show that a small but measurable number of mothers stop working altogether. These are more likely to be low-income people for whom the payoff for moving into work is smaller. Joseph Hotz and Mo Xiao, using a panel dataset across three census periods with extensive child-care center data, data on home care by state, and a host of control variables, find that tightening the staff-child ratio by one child reduces the number of child-care centers by 9.2 to 10.8 percent, without increasing employment levels at other centers.50 This reduced supply occurs exclusively in lower-income areas and leads to substitution to home daycare. Importantly, there is no evidence that increasing the stringency of this regulation improves quality. It simply reduces accessibility to formal care for the poor, making it more expensive and leading to substitution toward other care settings.

Staff qualification requirements also appear to have a big effect on prices. Thomas and Gorry find the requirement for lead teachers to have a high school diploma increases prices by between 25 and 46 percent. Hotz and Xiao likewise find that increasing the average required years of education of center directors by one year reduces the number of child-care centers in the average market by between 3.2 and 3.8 percent. Again, this effect manifests itself overwhelmingly in low-income areas, with quality improvements (proxied here by accreditation for the center) occurring in high-income areas.

Like housing, childcare is a sector where government regulations restrict the supply of the service to the financial detriment of the poor. For those on the margins of the labor market, child-care regulations can reduce the payoff to work. In return for these higher costs, there is little evidence that they yield much improvement in child-care quality. In fact, higher prices appear to cause demand substitution to potentially lower-quality childcare settings. (Though in the case of childcare, there is also a question about what “quality” actually means.)

Despite this evidence, some city and state governments continue undeterred. The D.C. government has passed regulations requiring teachers at child-care centers and caregivers at home-based centers to have associate degrees in early childhood education and assistant caregivers to obtain new child development associate certificates.51 Even if these do raise the quality of care, the requirements will further constrict supply — which is presumably why the District has delayed implementation and is engaged in new attempts to subsidize provision.52

Deregulation of staffing requirements could therefore significantly reduce prices to the benefit of the poor, who tend to put much less weight on the “quality” desired by richer families and regulators. The current costs of these regulations to low-income families are significant. The cautious end of Thomas and Gorry’s estimates suggests that even modest relaxation of staff-to-child ratios by one child at all age groups alone could reduce average child-care prices by $466 per year in Mississippi and $2,078 per year in Washington, D.C.53

Eliminating statutory regulations on child-care staffing entirely could reduce the cost of care even more significantly. Market mechanisms in the form of accreditation or certification agencies will arise if significant numbers of parents put a high premium on certain staffing structures and outcomes. Many major European countries already do not bother with mandated staff-to-child ratios, for example, seemingly with few ill effects.54

But extensive deregulation might be a leap too far for state policymakers. For the purposes of examining the cost of child-care regulations for a typical family with a young child in the poorest quintile, then, I assume that the “cost” of regulation equates roughly to the potential gains from a modest relaxation in the staff-child ratio, as outlined above. The net benefits to poor households of more extensive deregulation would be much larger. The broader economic benefits are greater still since lower prices allow more low-income family members to fulfill their labor market preferences.55

Food

The average household in the poorest 20 percent of the income distribution spent $3,682 on food in 2016 (15.4 percent of total spending and the highest proportion of any income group). Single-parent households spend proportionately more than other household types. Yet, the federal government makes groceries more expensive through such policies as milk-marketing orders, sugar programs, and ethanol mandates.

Milk-Marketing Orders. The federal government operates a byzantine system of marketing orders, price and income supports, and trade barriers in dairy markets.56

Federal milk-marketing orders set monthly minimum prices that dairy processors must pay dairy farmers in 10 regions. These account for around 60 percent of total production, with another fifth of the remaining 40 percent from California, which operates similar schemes at the state level.57 The marketing orders set regional prices for fluid milk and use complex formulae to determine nationwide prices for three other classes (soft manufactured products such as ice cream, hard cheese and cream cheese, and butter and dry milk).

The Milk Support Program supplements this with guarantees that the government will purchase any amount of cheese, butter, and dry milk from processors at a set minimum price. In order to ensure that these prices are not undercut by foreign producers, import barriers then insulate domestic dairy producers from competition through tariff rate quotas.

With modern storage techniques, there appears to be little need for this regional balkanization of the sector. The marketing orders and price supports stymie entrepreneurship and producers’ ability to provide low-cost milk to regions with higher milk prices. Import barriers further raise product prices and distort economic activity toward the dairy sector rather than allowing resources to be used most efficiently. The main economic effect of all this is higher average prices borne by consumers.

The best evidence of these price effects comes from Chouinard et al., who review the existing literature on what would happen if milk-marketing orders and associated supports were abolished.58 All studies suggest retail fluid milk prices would fall by between 15 and 20 percent. The effect on manufactured milk and processed dairy products is less clear. Averaging previous studies suggests butter and ice cream prices would fall by 3 percent and 1 percent respectively while, counterintuitively, fresh cream, coffee additives, and yogurt prices would increase by 1.3 percent and cheese prices would rise by 0.5 percent.59

The average poorest quintile household spent $246 per year on dairy products in 2016 ($97 on milk and fresh cream and $149 on other manufactured products).60 But this masks significant variation. The average single-parent family spends $353 on dairy products.61 African Americans, who are more likely to be in poverty, experience high rates of lactose intolerance, so spending on dairy products for poor whites is likely to be higher than the average figures suggest. The Consumer Expenditure Survey is not sufficiently disaggregated to calculate the cost of these programs to the average household in the poorest quintile. We need information about how consumers would react to price changes and how far they will substitute away from some dairy products to others to calculate net savings.

The Chouinard et al. model seeks to do just that. It suggests that “lower income families [would] benefit more than wealthier families” from eliminating federal milk-marketing orders, meaning the regulations currently are very regressive. They also find that families with young children benefit far more than the childless.

Their results suggest annual savings for white families with annual incomes of $10,000 from the abolition of federal milk-marketing orders of $44; $38 for those with incomes at $20,000; and $33 for those with incomes at $30,000. They estimate the regulatory burden for black families to be somewhere between a third and a half of this, meaning that the average black family would save somewhere between $14 and $22 per year.

Taking into account these differential racial burdens, the average household in the bottom quintile faces a current regulatory cost of approximately $38 per year from dairy interventions, and the average single-parent family a higher cost of $54 per year.62

Sugar intervention. In similar fashion, the U.S. federal government also effectively cartelizes the sugar market. As Cato scholar Colin Grabow has explained in detail, the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) facilitates loans to sugar processors using raw sugarcane and refined beet sugar as collateral, effectively creating a floor for the domestic sugar price.63 To ensure that loans will likely be repaid, it then restricts the supply of domestic sugar through allotment quantities, raises demand by making purchases, and limits the amount of sugar that can be imported either without tariffs or with low tariffs.

Unsurprisingly, these anti-competitive actions, which restrict supply and inflate demand, raise domestic sugar prices substantially. Data from the USDA show that in March 2018 the U.S. raw sugar price was 24.73 cents per pound, almost double the world price of 12.83 cents.64 Not only do consumers pay higher retail prices for sugar but they also pay more for manufactured foods that contain sugar as an ingredient.

Economic analysis of the consumer cost of the program has examined the aggregate effect on consumers. Economist Michael Wohlgenant has suggested that the burden amounts to $2.4 billion per year, or an average of around $19 per household.65 A 2017 paper by John Beghin and Amani Elobeid estimated the loss to consumer welfare from the sugar program at between $2.4 billion and $4 billion in 2009 dollars.66 Adjusted for inflation, that is equivalent to $2.8 billion to $4.7 billion today.

This suggests that the program costs between $22 and $36 per year for the average household.67 Determining a more precise figure for low-income households is fraught with difficulty. On the one hand, poorer households tend to contain fewer people, and on the other, some evidence suggests overall sugar consumption is highest among those with the lowest incomes.68

In the absence of more complete evidence, I take the midpoint of these household estimates and assume that the costs of the program are spread evenly across individuals, such that the average poor household (with 1.6 members) is $18 per year worse off as a result of the policy, and the average single-parent family (with 2.9 members) is $33 worse off.

Renewable Fuel Standard. The federal Renewable Fuel Standard (RFS) mandates quotas for the amounts of biofuels blended into transportation fuel sold. The origins of the standard are the Energy Policy Act of 2005, which amended the Clean Air Act, and the Energy Independence and Security Act of 2007, which expanded the ethanol mandates.

These regulations raise food prices for consumers. The increased demand for corn for biofuels raises the prices of corn and corn-based products directly. This higher price then raises production costs for meat and dairy products, since corn is used as animal feed. Dedicating agricultural land to growing corn also restricts available land supply for other crops, such as soybeans, raising their price too.

A 2009 Congressional Budget Office (CBO) analysis found that demands for ethanol subsequently raised total food spending by between 0.8 and 1 percent.69 This corroborates the work of Richard Perrin, who estimated that growth in demand for ethanol raised overall food prices by 1 to 2 percent in 2008.70 But how much consumers would benefit financially from the repeal of the RFS at any given time depends on the oil price.

In 2014, when oil prices were much higher than today, CBO analysis suggested “suppliers would probably find it cost-effective to use a roughly 10 percent blend of corn ethanol in gasoline in 2017 even in the absence of the RFS,” meaning that total food spending would fall only very slightly were the RFS repealed (by 0.1 percent).71 Today, however, oil prices are significantly lower, meaning that there is a bigger incentive to use relatively more oil in gas production.

Given that the price of oil today falls between the levels seen in 2008 and 2009, I assume that the RFS currently raises food prices by 1 percent. Assuming that food spending is price inelastic, the direct cost of this policy can be estimated at about $39 per year for the average family in the lowest income quintile, or $58 for the average single-parent family.72

Transport

The average household in the bottom 20 percent of the income distribution spent $3,767 on transport in 2016 (15 percent of total spending). The vast majority was on private vehicles: $1,332 on vehicle purchases; $902 on gasoline and motor oil; and $1,308 on other vehicle expenses.73 Just $225 was spent, on average, on public transportation.

Averages mask the real experience of families, of course. Whereas 9 percent of all households do not have a vehicle,74 this increases to 20 percent for households in poverty and 11 percent for households with incomes at 100 to 200 percent of the federal poverty level. Spending on motor vehicles for vehicle-owning households is therefore higher than the figures above suggest.75

Two government regulations increase motoring costs: Corporate Average Fuel Economy Standards at the federal level and dealership franchise laws at the state level. These not only increase transport costs for the poor directly, but also make it more difficult for poor families to have physical accessibility to jobs, health care, training, and childcare.76

Corporate Average Fuel Economy Standards. First created in 1975, Corporate Average Fuel Economy Standards (CAFE) sought to increase the fuel economy of cars and trucks to limit dependence on foreign oil. It was originally thought that consumers undervalued fuel savings from more efficient vehicles, though recent research suggests fears over consumer short sightedness were overstated.77 Now CAFE standards are justified as a tool to reduce carbon emissions.

The regulations require manufacturers to achieve a sales-weighted fuel economy average for car and light-truck fleets. Their stringency has increased since they were tied to a vehicle’s physical footprint beginning in 2012. President Barack Obama had agreed to raise the standards significantly from 2022 through 2025, to 60 miles per gallon for small cars and 46 for large cars, and 50 miles per gallon for small trucks and 30 for large trucks. But President Trump has outlined plans to relax these rules.78 More recently, the administration proposed freezing the standards entirely at 2020 levels and preventing states (particularly California) from unilaterally imposing stricter regulations.79

CAFE standards increase costs to consumers overall, although the effects are not uniform across vehicles. Meeting fuel economy standards requires high fixed-cost investments in technological improvements by manufacturers. But to hit the sales-weighted averages, manufacturers have to adjust prices to incentivize purchases. Evidence suggests consumers prefer larger, more powerful vehicles. Firms therefore have to offer discounts for smaller, more fuel-efficient models, cross-subsidized by higher prices for larger vehicles. Increased prices for new cars lead to higher prices in the used car market too, as consumers substitute toward older models of the larger vehicles they tend to prefer.

It is beyond the scope of this paper to assess the merits of curbing carbon emissions. Economists are, in any case, doubtful this type of policy will have large effects on emissions, not least because making vehicles more expensive leads consumers to keep older, less fuel-efficient cars on the road longer and incentivizes owners of the more efficient cars to drive more.

If one is worried about the externality of carbon emissions, theory and evidence show that CAFE standards have more regressive effects than an equivalent gas tax for such a goal.80 CAFE standards are roughly equivalent to a tax on the gasoline used per mile of travel. The difference between the consumption of rich and poor on this metric is lower than the total gas consumed. This makes CAFE standards more regressive than a simple gas tax. Additionally, larger vehicle categories also face less stringent standards. The fact that vehicle size tends to increase with income exacerbates the regressive impact of the standards.

Economists Lucas Davis and Christopher Knittel estimate the implicit tax from CAFE standards in 2012 to be around $180 per vehicle for those in the poorest income quintile.81 Adjusted for inflation, that’s more like $194 today.82 The standards have become much more stringent since then, suggesting the effect today would be far larger.

Other academic studies find larger effects for broader long-term consumer welfare losses (which include the welfare costs of substituting away from preferred vehicles). In today’s prices, for example, Mark Jacobsen estimates a long-run consumer surplus loss of $226 for every one-mile-per-gallon standard increase for people with incomes below $25,000.83 Assuming that this effect was linear (we might assume the marginal cost increases with the standard), this implies that the tightened standards seen between 2011 and 2018 caused consumer welfare losses of more than $2,230 per vehicle. If the standards planned by President Obama were implemented through 2025, this loss would more than double.84 This corresponds closely to figures from much older studies. David Greene found that for every one-mile-per-gallon increase in vehicle fuel economy, the average per-vehicle cost was from $225 to $450 in today’s prices, and figures of these magnitudes have been corroborated in a broader review of the literature.85

Given that the average used car price is now around $20,000, this suggests the ratchet in standards since 2011 is likely to account for over 10 percent of the price of a used vehicle.86 A 10 percent reduction in vehicle prices would save the average poorer household $133 and the average single-parent family $307 annually.87

This appears to be a reasonable estimate. A 2015 paper by Mark Jacobsen and Arthur van Benthem estimated that the standards enacted in 2012 would cause used vehicle prices to rise by $103 per year relative to the old standards enacted in 2007.88 An earlier paper by David Austin and Terry Dinan found an annual cost per vehicle per year of $153 for an increase in the standards of just under 4 miles per gallon.89 More recently, the Reason Foundation’s Julian Morris estimated that the average price of a new pickup truck has risen by 25 percent since 2013, overwhelmingly because of the CAFE standards. That works out to a net cost of about $100 per year.90

While a range exists, all these estimates suggest CAFE standards increase new and used vehicle prices for consumers. Theory and evidence suggests the effects are regressive. While manufacturers are unlikely to undo technological changes that have delivered improved fuel efficiency, President Trump’s planned policy of capping standards at 2020 levels would deliver significant annual savings for purchasers of vehicles relative to the trajectory planned by President Obama.

Dealership Franchise Laws. Every state has laws governing the economic relationships of car manufacturers with new car dealers. These require dealers to be licensed and can also incorporate restrictions on when franchise relationships can be terminated, canceled, or transferred, restrictions on opening new dealerships in existing market areas, and requirements that manufacturers buy back vehicles or other accessories when a dealership franchise is terminated.91

The most prominent effect of these laws is the restriction of direct sales by manufacturers. But the broad effect of all of them is to insulate dealerships from competition and prevent manufacturers from optimizing their inventory and distribution to best match the demands and preferences of consumers.

“Good cause” regulations, for example, mean manufacturers can only terminate a franchised dealership for a set of enumerated reasons, often not including efficiency. Manufacturers can face penalties and charges if they terminate dealerships because of demand patterns. Though states often allow termination for noncompliance of a franchise agreement, even then the manufacturer faces the burden of proof in showing that they have acted in good faith, the termination is reasonable, and they have given notice with an opportunity for the franchisee to deal with the issue at hand.

Plenty of states have laws that protect existing franchisees from “encroachment” too. Manufacturers must show the need for a new dealership if it is proposed within the same relevant market area as an existing one. Protection of exclusive territories creates effective monopoly power for dealers, raising profits, when manufacturers might prefer to increase the quantity of sales.

These regulations were justified in the early 20th century as correcting for asymmetric information between the franchiser (the manufacturer) and the franchisee (the dealer) that led to manufacturers exploiting dealers. But today, calls for auto dealership laws are based on the supposed “social benefits” of dealerships, including their roles in the community and as sponsors of local events. Because such claims could be made about all local businesses, they do not provide robust “market failure” justifications for the interventions.

These regulations raise consumer prices, though the magnitudes of the effect are disputed. A paper exploring data from 1972 suggested that new car prices were raised by around 9 percent.92 A report for the Federal Trade Commission in 1986 found an average price increase of just over 6 percent across all car types.93 In 2001, the Consumer Federation of America summarized the existing literature, concluding that these laws raised new automobile prices by between 6 and 8 percent.94 This was subsequently questioned by the National Automobile Dealers Association, which concluded that the true effect was much lower, at 2.2 percent.95 But papers focusing on other countries have found effects similar to the 2001 study.96

Unfortunately, little modern evidence exists on this subject, and it is beyond the scope of this paper to develop new calculations. The internet may have helped to reduce some of the burden on consumers, and though the price effects will induce substitution to the used car market, we perhaps would not expect prices to be affected to the same extent. Given the best estimates from older work, the average regulatory cost on a household in the bottom quintile is likely to be around $61 annually, or $140 for the average single-parent family.97

Apparel and footwear

In 2016, the average household in the bottom income quintile spent $860 on apparel and footwear, or 3.4 percent of overall spending — the highest proportion of any income quintile.98 The average single-parent household put 4.5 percent of total expenditure toward these goods.99 The poor spend a disproportionate amount on clothing and footwear, and family structures most likely to be recipients of means-tested welfare programs (single-parent households) spend most of all.

Yet the federal government makes clothing and footwear more expensive through import tariffs, which are often higher than those imposed on other goods. The United States raised $33.1 billion overall in tariff revenue in 2017, but $14 billion of that came from tariffs on apparel and footwear alone. These items account for 4.6 percent of the value of U.S. imports, but 42 percent of duties paid. The average effective tariff rate for U.S. imports overall is just over 1.4 percent. Rates for apparel and footwear are 13.7 percent and 11.3 percent, respectively.100

The Cato Institute’s Daniel Ikenson has examined the evolution of clothing and textile protectionism.101 He concludes that such high tariffs do not exist to protect domestic apparel manufacturing. Data from the U.S. Trade Representative estimated that 91 percent of manufactured apparel goods and 96.5 percent of footwear are imported despite the tariffs.102 In February 2018, just 116,400 people were employed in domestic apparel manufacturing, a collapse from 939,000 in January 1990.103

Why then are such highly regressive tariffs imposed? The answer appears to be the lobbying efforts of the capital-intensive U.S. textile industry. Textiles are the major input for labor-intensive apparel production, which largely occurs overseas. To quote Ikenson:

The U.S. textile industry insists on preserving those tariffs as leverage to compel foreign apparel producers to purchase their inputs. Preferential access [to U.S. markets] is conditioned on use of U.S. textiles. The high rates of duty apply, generally, to all “normal trade relations” partners. But those duties are much lower or excused entirely for trade agreement partners, provided that the finished garment comprises of textiles made in countries that are signatories to the agreement.104

U.S. consumers pay the price of this protectionism, and poorer consumers especially. In fact, protectionism is doubly regressive. Not only do poorer households spend relatively more on clothes and footwear, but Edward Gresser’s work has shown how often luxury clothes and shoes face lower tariff rates than inexpensive products.105

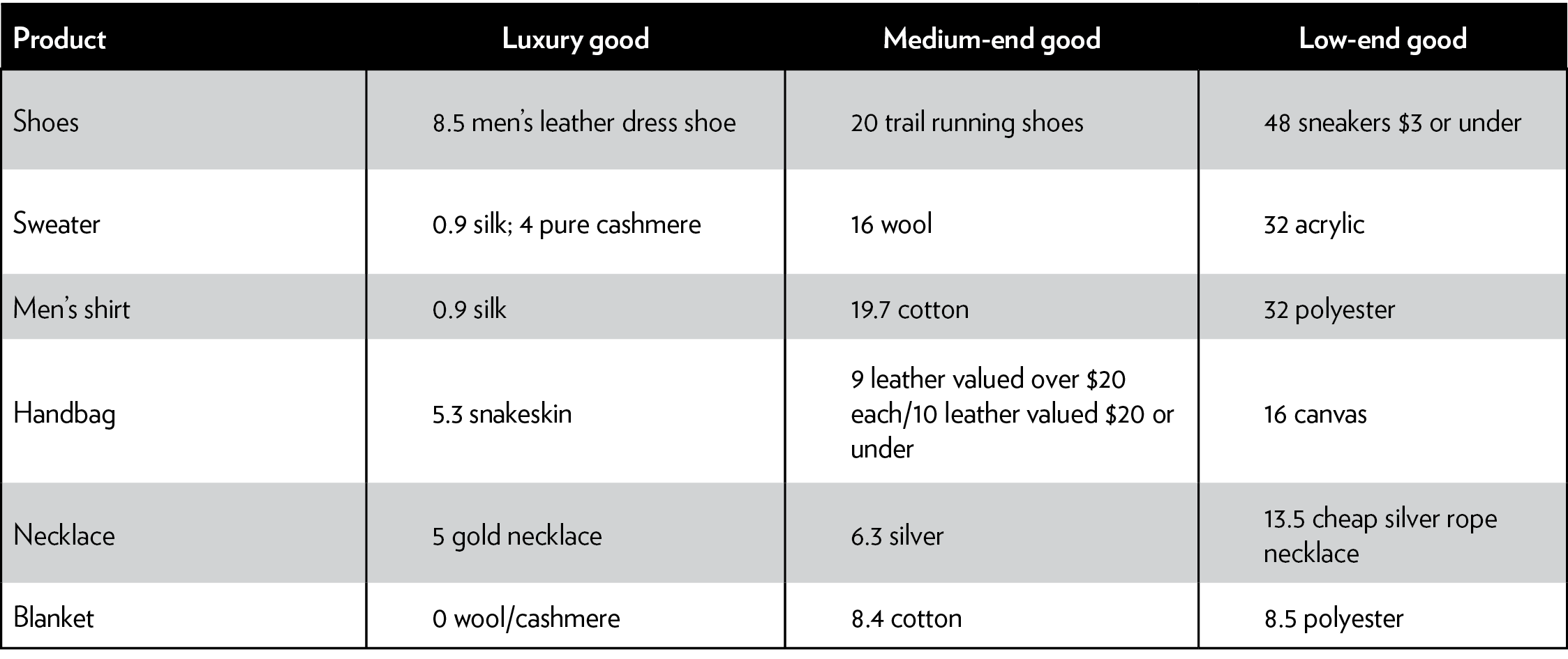

Consider Table 3 (an updated version of Gresser’s work) below. Where duties are applicable, a pure cashmere sweater import incurs a 4 percent tariff, a wool sweater a 16 percent tariff, and an acrylic sweater a whopping 32 percent. Men’s silk shirts would see a 0.9 percent tariff, cotton shirts a 19.7 percent tariff, and cheaper polyester shirts a 32 percent tariff. Leather dress shoes have an 8.5 percent tariff, whereas cheap sneakers would see a 43 percent tariff. Windbreakers, leggings, tank tops, and other clothes made cheaply from synthetic fabrics face a 32 percent tariff if sourced from countries that the United States does not have a free-trade agreement with.

Table 3: Regressive tariffs (percentage on various goods)

Source: United States International Trade Commission, Tariff Database, https://dataweb.usitc.gov/scripts/tariff.asp

Note: The codes needed to find tariff rates for these products are: 64035960, 64029142, 64029160, 61109010/61101210, 61103030, 61059040, 61051000, 61052020, 71131921, 71131110, 71131120, 63012000, 63013000.

Assuming poorer households tend to buy cheaper products, these differential tariffs have perniciously regressive effects. (And not just for clothes; as Table 3 shows, similar trends are seen for consumer goods such as handbags, necklaces, and blankets).

It is difficult to calculate the true overall cost of these tariffs to poor families. That would require detailed information on the effect on domestic substitute goods prices, knowledge of products bought by poor families and their propensity to import in the absence of protectionism.

Nevertheless, we can develop cautious lower-bound estimates of the financial cost. The average household in the poorest income quintile spends $655 on apparel and $206 on footwear per year. Assuming the import propensities for the population as a whole apply to poorer people implies $595 of apparel spending and $199 of footwear spending is on imported goods. Taking average effective tariff rates for apparel and footwear for this spending (13.7 and 11.3 percent) implies a combined direct tariff cost of $92 per year for the average household in the poorest income quintile, or $204 per year for the average single-parent household.106

These figures underestimate the true burden, though, because they only represent the direct cost from current spending on imported goods. They assume tariffs do not raise domestically produced goods prices, though in reality the anti-competitive effect of the tariffs would be expected to raise prices here too. The calculation also assumes the same effective tariff rates for apparel and footwear apply for the poorest households as for the whole population, but we have seen that products that the poor are more likely to buy tend to face higher tariff rates. Consumer welfare losses from tariffs are higher than the implied savings here, of course, since tariffs make consumers less willing to buy imported products that they would otherwise prefer.

Nevertheless, these figures correspond well to calculations by Jason Furman, Katheryn Russ, and Jay Shambaugh that provide an estimate of the overall tariff burden (all goods, not just apparel and footwear) of around $100 and $238 per year for poorer and single-parent households, respectively.107

Occupational Licensing

State governments regulate numerous occupations through education, training, or test requirements, creating barriers to entry to practicing a trade. This restricts the supply of providers within the state and discourages movement of professionals across state lines, raising the price of services.

Licensing gets justified on grounds of imperfect information between buyer and seller, particularly when harm could result from low-quality service. This argument is most forcefully made about medical professionals, where it is argued that “quack” practitioners might do substantial harm to patients. Yet restrictions on entry come with tradeoffs, including higher prices and deterring talented people from entering a profession. Ideally, one must weigh up any benefits of reduced quackery against these supply-restricting consequences.

Other sectors commonly licensed include hair braiding, barbers, and sign-language interpreters, where any costs associated with low-quality providers are likely much smaller. In these cases, consumers are best placed to judge a price-quality bundle, and intermediate institutions such as online rating sites can provide information about the nature and quality of service. Markets may even deliver certification mechanisms for safety- or quality-sensitive customers. Instead, licensure boards are often dominated by existing providers with a vested interest against competition. The arguments that licensure corrects for some “market failure” are therefore increasingly difficult to justify. Yet 25 to 30 percent of Americans now work in licensed occupations.108

A plethora of research has found licensure raises wages in licensed sectors (relative to no licensure or no certification). A recent study found that “having a license when it is not required has no influence on wage determination, but, when it is required, licensing raises wages by 7.5 percent,” even controlling for a host of worker and occupational characteristics.109

Whether this raises prices depends on whether consumers would demand equally robust entry barriers in the form of certification absent government intervention. Without licensure constraints, prices of services are likely to be lower, unless state governments provide economies of scale in license provision relative to private certificates. However, in many cases consumers are unlikely to demand substitute certification at all, and so the wage premium would evaporate.

Research on individual markets confirms this intuition. Relaxing licensing laws to allow nurse practitioners to perform tasks without medical doctor supervision was found to reduce well-child exam prices by between 3 and 16 percent.110 Delicensing of funeral servicing providers in Colorado lowered funeral prices significantly.111 Older papers estimated that dental assistant and hygienist licensing raised prices of dental visits by between 7 and 11 percent, and optician licensing the price of eye care by between 5 and 13 percent.112

Two attempts have been made to estimate the aggregate costs of occupational licensing to consumers. Morris Kleiner, Alan Krueger, and Alex Mas estimated a $203 billion annual cost, or $1,567 per household.113 The Heritage Foundation’s Salim Furth estimates a lower figure, with a cost to the average household of $1,033 per year.114

Ideally, we would produce a more accurate estimate using detailed data of the cost of licensure by sector mapped against spending patterns for poor households. We know, for example, that poorer households spend relatively more on health care than richer households but also that richer households spend more on other grooming services affected by the licensure premium. Poorer households are likely to be more price sensitive and less discerning about “quality.” One must bear in mind, too, that because licensing restricts people from practicing certain occupations, the potential labor supply is increased in nonlicensed sectors, putting downward pressure on labor costs and hence prices in other industries.

Bearing these caveats in mind, I assume that the total spending ratio of poorer and single-parent households to the average household is the same as the ratio of spending on licensed services between the groups. Using the household costs of licensure from Kleiner and Furth implies an average annual cost to poorer households of between $450 and $690 per year, and between $760 to $1,160 per year for the average single-parent household.115 Again, this is a lower bound to the true economic costs for poorer people, not least because occupational entry barriers prevent individuals from taking up new and better job opportunities because of the time and financial costs of meeting the licensure requirements.

Conclusion

This paper has demonstrated how government interventions raise the cost of living for poor and single-parent households.

Debates on policies to help the poor tend to focus on redistribution, tax breaks, minimum wage hikes, and government-provided services. But liberalizing reform in the markets outlined above could improve the financial well-being of less well-off households without new government expenditure or risky labor-market interventions. A “cost-based” approach to poverty alleviation should be considered a key tool in helping the less well-off.

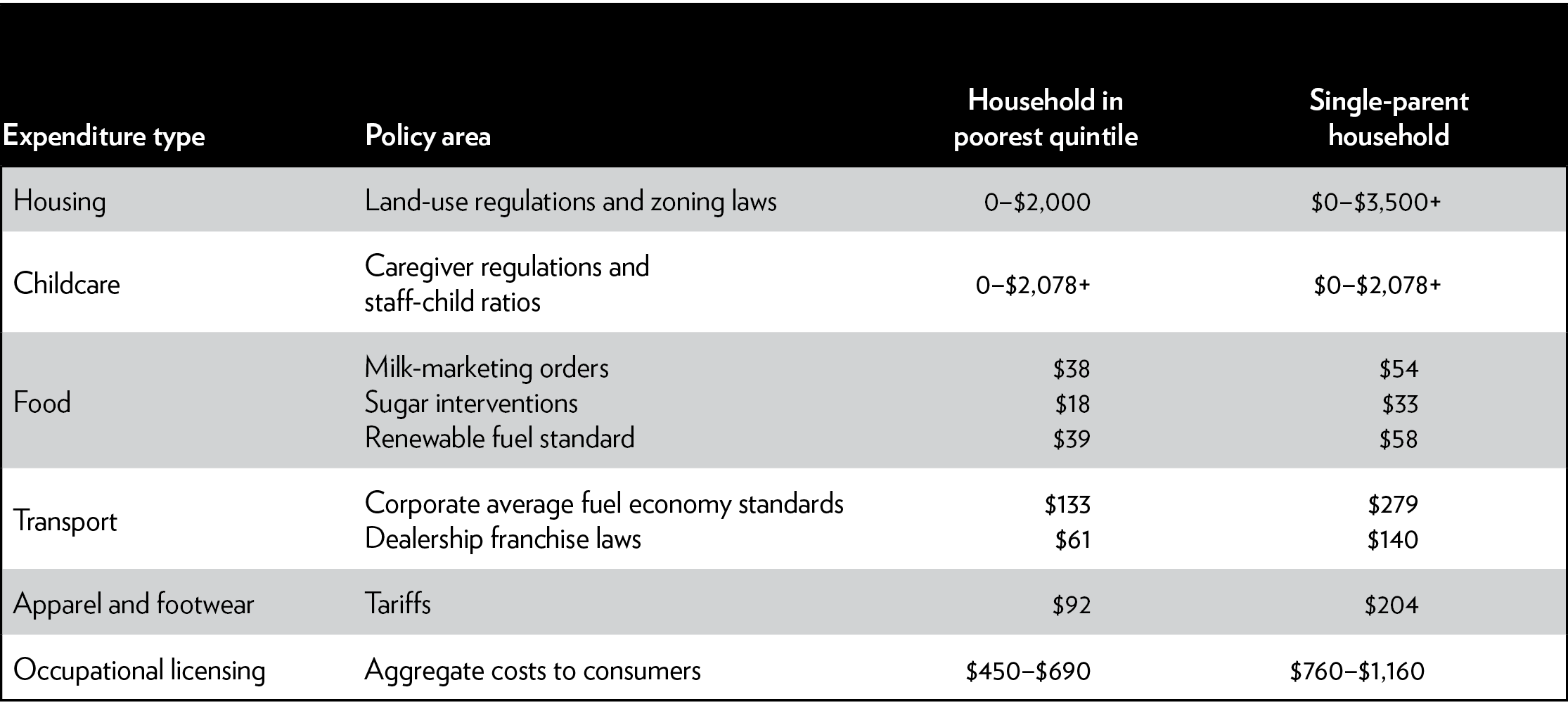

Table 4 summarizes the estimated direct costs to poorer and single-parent households of existing interventions. These are based on extremely cautious assumptions and likely understate the true financial impacts. The ranges are wide, reflecting differences in household location and composition. However, a reasonable central range for poorer households would be a lower bound cost of $830 per year for a household with no children living in a rural area, up to $3,500 for a poor family living in an expensive city such as New York with a young child in full-time infant care.116

Table 4: Summary of costs of interventions on the poor and single parents (dollars per year)

Source: Author’s calculations applied largely through the Bureau of Labor Statistics Consumer Expenditure Survey, https://www.bls.gov/cex/.

Note: Housing costs range from areas with no effective regulatory tax through to the implied regulatory tax in expensive cities (adjusted to relative spending by poor and single-parent households). Child-care costs range from $0 for those with no young children in infant care to the implied savings from relaxing staff-child ratios by one child in the most expensive region for childcare (D.C.). Milk-marketing order costs calculated using information from Chouinard et al. Sugar program costs calculated applying per person midpoint cost of Beghin and Elobeid cost estimate, multiplied by average household numbers for poor and single-parent families. Renewable food standard cost based on 1 percent uplift in food prices applied to food spending levels. Corporate average fuel economy standards cost calculated as 10 percent increase in vehicle prices applied to vehicle purchase spending levels. Dealership franchise laws cost assumes new vehicle prices are increased by 6 percent and used car prices by 4 percent as a result of the regulations. Tariff costs estimated on current spending levels by poor and single-parent households, based on whole population import propensities and average effective tariff rates on apparel and footwear. Occupational licensing costs based on the average cost of licensure per household estimates from Kleiner et al. and Furth adjusted for spending levels of the poor and single parents. For more information on the assumptions behind these calculations, see the discussion in relevant sections of the paper.

The figures here relate only to the direct effects of these policies on prices and so ignore the broader effect on productivity and market incomes. For land-use and zoning laws, child-care regulations, policies that increase driving costs, and occupational licensure these secondary effects could be very large indeed. Liberalization could improve labor mobility, willingness to move into the labor market, and job options available to the unemployed and existing low-paid workers.

The calculations are cautious for other reasons. Estimates of the cost of sugar interventions and tariffs on clothing and footwear assume that the poor have the same consumption habits as the broader population, though there are reasonable grounds to suspect the cost borne by them is even higher. The cost of child-care regulations is pegged at the savings from very modest relaxation of existing staffing regulations, rather than full repeal, which could deliver huge price reductions. This analysis also ignores regressive interventions in other areas where the poor spend significant amounts, especially health care and utilities.

Individual households will face very different costs depending on exactly where they live, whether they have young children, their means of transportation, and other spending tastes and preferences. This paper has shown, though, that a “cost-based” reform agenda could deliver major financial savings for poor families.

A concerted anti-poverty agenda across all levels of government overturning these damaging policies could have political benefits too. The lower cost of living would lessen political demands for government to redistribute income. The aspirations of the “living wage” campaign would be much more likely to be achieved, but through lower living costs rather than demands for states or cities to raise minimum wages. Better financial outcomes for the poor through market activity might lead to greater support for economic liberalization in other sectors.

Reform would be politically challenging. But with the federal finances suffering from large and growing imbalances and widespread concern about the future of labor markets, now is an opportune time for a new approach to assist those on low incomes. For too long an obsessive focus on the role of government transfers and minimum wage laws in alleviating poverty has blinded campaigners and politicians to areas where existing policies raise living costs. We should aspire to undo this damage, rather than doubling down on a more interventionist agenda that, in part, seeks to treat the symptoms of current mistakes.

Notes

1. Michael Tanner, “The American Welfare State: How We Spend Nearly $1 Trillion a Year Fighting Poverty—and Fail,” Cato Institute Policy Analysis no. 694, April 11, 2012, https://www.cato.org/publications/policy-analysis/american-welfare-state-how-we-spend-nearly-%241-trillion-year-fighting-poverty-fail.

2. See discussion of theories of causes of poverty in Michael Tanner, The Inclusive Economy: How to Bring Wealth to America’s Poor, Cato Institute, forthcoming, December 2018.

3. Sean Higgins, “Democrats Officially Introduce $15 Minimum Wage Bill,” Washington Examiner, May 25, 2017.

4. See “A Living Wage,” BernieSanders.com, https://berniesanders.com/issues/a-living-wage/; and “Early Childhood Education,” HillaryClinton.com, https://www.hillaryclinton.com/issues/early-childhood-education/.

5. Ryan Bourne, “A Jobs Guaranteed Economic Disaster,” Cato at Liberty, Cato Institute, April 24, 2018, https://www.cato.org/blog/jobs-guaranteed-economic-disaster.

6. Dylan Matthews, “Hillary Clinton Almost Ran for President on a Universal Basic Income,” Vox.com, September 12, 2017; see also Charles Murray, “A Guaranteed Income for Every American,” Wall Street Journal, June 3, 2016.

7. Ramesh Ponnuru, “Tax Relief for Parents,” Statement before the Senate Committee on Finance on “Individual Tax Reform,” September 14, 2017, http://www.aei.org/publication/tax-relief-for-parents/; and Sen. Mike Lee, “Sens. Lee and Rubio to Introduce Child Tax Credit Refundability Amendment,” November 29, 2017, https://www.lee.senate.gov/public/index.cfm/2017/11/sens-lee-and-rubio-to-introduce-child-tax-credit-refundability-amendment.

8. “A Better Way: Our Vision for a Confident America,” Poverty, Opportunity, and Upward Mobility, June 7, 2016, https://abetterway.speaker.gov/_assets/pdf/ABetterWay-Poverty-PolicyPaper.pdf.

9. For example, it is widely acknowledged that policies that seek to ameliorate climate change by raising the cost of carbon emissions hit the poor hard. But the objective of these policies is to internalize the social costs of carbon, which theoretically raises overall economic efficiency. Though one can debate whether existing policies do this well, or whether they are needlessly regressive, this paper avoids issues where these kinds of judgments are required, instead focusing on areas where market failure arguments are weak and the policies have clear regressive effects.

10. Arloc Sherman, “Official Poverty Measure Masks Gains Made over Last 50 Years,” Center for Budget and Policy Priorities, September 13, 2013, https://www.cbpp.org/research/official-poverty-measure-masks-gains-made-over-last-50-years.

11. Bruce D. Meyer and Derek Wu, “The Poverty Reduction of Social Security and Means-Tested Transfers,” NBER Working Paper no. 24567, May 2018, http://www.nber.org/papers/w24567.

12. David Neumark, “Reducing Poverty via Minimum Wages, Alternatives,” Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco Economic Letter no. 2015-38, December 28, 2015, https://www.frbsf.org/economic-research/publications/economic-letter/2015/december/reducing-poverty-via-minimum-wages-tax-credit/.

13. Bruce Meyer and James Sullivan, “Winning the War: Poverty from the Great Society to the Great Recession,” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, Fall 2012, https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/2012b_Meyer.pdf.

14. Congressional Budget Office, The Budget and Economic Outlook: 2018 to 2028, April 2018.

15. Congressional Budget Office, The 2017 Long-Term Budget Outlook, March 2017.

16. See Karel Martens and José L. Montiel Olea, “Marginal Tax Rates and Income: New Times Series Evidence,” NBER Working Paper no. 19171, September 2017, http://www.nber.org/papers/w19171; and Robert J. Barro and Charles J. Redlick, “Macroeconomic Effects from Government Purchases and Taxes,” NBER Working Paper no. 15369, December 2011, http://www.nber.org/papers/w15369. Concerning the latter, Barro states in the Wall Street Journal that “My research with Charles Redlick, published in 2011 by the Quarterly Journal of Economics, suggests that cutting the average marginal tax rate for individuals by 1 percentage point increases gross domestic product by 0.5% over the next two years.” Robert J. Barro, “Tax Reform Will Pay Growth Dividends,” Wall Street Journal, January 4, 2018.

17. See David Neumark and Cortnie Shupe, “Declining Teen Employment: Minimum Wages, Other Explanations, and Implications for Human Capital Investment,” Mercatus Center Working Paper, February 7, 2018, https://www.mercatus.org/publications/declining-teen-employment-minimum-wage-human-capital-investment.

18. See summary of the literature in Ryan Bourne, “A Seattle Game-Changer?,” Regulation 40, no. 4 (Winter 2017–2018): 8–11, https://object.cato.org/sites/cato.org/files/serials/files/regulation/2017/12/regulation-v40n4-6.pdf.

19. Neil Irwin, “The Unemployment Rate Rose for the Best Possible Reason,” New York Times, July 6, 2018.

20. In Britain, working-age welfare bore a hugely disproportionate share of the deficit reduction measures seen following the general election during 2010.

21. Andrew Hall and Jesse Yoder, “Does Homeownership Influence Political Behavior? Evidence from Administrative Data,” Department of Political Science, Stanford University, August 7, 2018.

22. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Consumer Expenditure Survey, Metropolitan Statistical Area Tables, https://www.bls.gov/cex/tables.htm#MSA.

23. Child Care Aware of America, “2017 Appendices: Parents and the High Cost of Child Care,” http://usa.childcareaware.org/costofcare.

24. The costs to the average poor household of anti-competitive, regressive regulations would be higher still if we also examined some utilities and health care interventions; but that is beyond the scope of this paper.

25. Pew Charitable Trusts, “Household Expenditures and Income,” March 2016. The poorest quintile are more likely to be renters: 61 percent of households in the bottom quintile and 66 percent of single-parent households rent, compared to just 15 percent of households in the top income quintile; see Bureau of Labor Statistics, Consumer Expenditure Survey 2016, Table 1101, Quintiles of income before taxes, and Table 1502, Composition of consumer unit.

26. Demographia, “14th Annual Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey: 2018,” January 22, 2018, http://demographia.com/dhi.pdf. It is worth noting that Demographia limits its analysis to metropolitan areas with populations of 1 million people or more.

27. Crystal Chen, “Zumper National Rent Report: March 2018,” Zumper.com, February 28, 2018.

28. Edward L. Glaeser, Joseph Gyourko, and Raven Saks, “Why Is Manhattan So Expensive? Regulation and the Rise in Housing Prices,” Journal of Law and Economics 48, no. 2 (October 2005): 331–69.

29. Vanessa Brown Calder, “Zoning, Land-Use Planning, and Housing Affordability,” Cato Institute Policy Analysis no. 823, October 18, 2017, https://www.cato.org/publications/policy-analysis/zoning-land-use-planning-housing-affordability.

30. Stephen Malpezzi, “Housing Prices, Externalities, and Regulation in U.S. Metropolitan Areas,” Journal of Housing Research 7, no. 2 (1996): 209–41.

31. Raven Saks, “Job Creation and Housing Construction: Constraints on Metropolitan Area Employment Growth,” Finance and Economics Discussion Series, Divisions of Research and Statistics and Monetary Affairs, Federal Reserve Board, Working Paper no. 2005-49, September 22, 2005.

32. Keith R. Ihlanfeldt, “The Effect of Land Use Regulation on Housing and Land Prices,” Journal of Urban Economics 61, no. 3 (May 2007).

33. Chang-Tai Hsieh and Enrico Moretti, “Why Do Cities Matter? Local Growth and Aggregate Growth,” Econometrics Laboratory, University of California, Berkeley, Working Paper, April 2015.

34. Rebecca Diamond, Timothy McQuade, and Franklin Qian, “The Effects of Rent Control Expansion on Tenants, Landlords, and Inequality: Evidence from San Francisco,” NBER Working Paper no. 24181, January 2018, http://www.nber.org/papers/w24181.

35. Vanessa Brown Calder, “Zoning, Land-Use Planning, and Housing Affordability.”

36. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Consumer Expenditure Survey 2016, Tables 3004, 3024, and 3033.

37. Jordan Weissman, “So You’re Rich for an American. Does That Make You Rich for New York?” Slate Moneybox, August 29, 2014.

38. Calculation by author subtracting Glaeser et al. estimate of implied regulatory tax for New York (12.2 percent) from average New York household expenditure on shelter of $16,882 in 2016 (taken from Consumer Expenditure Survey 2016, Table 3004). This implies regulation raises average household expenditure by $1,836 per year. Given those in the poorest quintile, on average, spend 57 percent of average household expenditure on shelter across the whole of the United States (Consumer Expenditure Survey 2016, Table 1101), this suggests these households pay $1,044 more for shelter than they would if the regulatory tax was zero.

39. Child Care Aware of America, “2017 Appendices: Parents and the High Cost of Child Care,” Appendix I: 2016 Average Annual Cost of Full-Time Center-Based Child Care by State, http://usa.childcareaware.org/costofcare.

40. Child Care Aware of America, “2017 Appendices: Parents and the High Cost of Child Care,” Appendix III: 2016 Ranking of Least-Affordable Center-Based Infant Care, http://usa.childcareaware.org/costofcare.

41. Dawn Lee, “State Child Care Assistance Programs,” Single Mother Guide, January 10, 2018, https://singlemotherguide.com/state-child-care-assistance/.

42. OECD, Society at a Glance 2016: OECD Social Indicators (Paris: OECD Publishing, 2016), Figure 1.14. Childcare costs are around 15% of net family income across the OECD. Out-of-pocket childcare costs for a single parent: full-time care at a typical childcare center, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264261488-en.

43. Rachel Connelly and Jean Kimmel, “The Effect of Child Care Costs on the Employment and Welfare Recipiency of Single Mothers,” Southern Economic Journal 69, no. 3 (January 2003): 498–519, https://www.jstor.org/stable/1061691?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents.

44. Allison Linn, “Opt Out or Left Out? The Economics of Stay-at-Home Moms,” NBC News, May 12, 2013.