Private individuals and policymakers often utilize prohibition as a means of controlling the sale, manufacture, and consumption of particular goods. While the Eighteenth Amendment, which was passed and subsequently repealed in the early 20th century, is often regarded as the first major prohibition in the United States, it certainly was not the last. The War on Drugs, begun under President Richard Nixon, continues to utilize policies of prohibition to achieve a variety of objectives.

Proponents of drug prohibition claim that such policies reduce drug-related crime, decrease drug-related disease and overdose, and are an effective means of disrupting and dismantling organized criminal enterprises.

We analyze the theoretical underpinnings of these claims, using tools and insights from economics, and explore the economics of prohibition and the veracity of proponent claims by analyzing data on overdose deaths, crime, and cartels. Moreover, we offer additional insights through an analysis of U.S. international drug policy utilizing data from U.S. drug policy in Afghanistan. While others have examined the effect of prohibition on domestic outcomes, few have asked how these programs impact foreign policy outcomes.

We conclude that prohibition is not only ineffective, but counterproductive, at achieving the goals of policymakers both domestically and abroad. Given the insights from economics and the available data, we find that the domestic War on Drugs has contributed to an increase in drug overdoses and fostered and sustained the creation of powerful drug cartels. Internationally, we find that prohibition not only fails in its own right, but also actively undermines the goals of the Global War on Terror.

Related Event

Pernicious Infusion: How Racism Pervades the Drug War, Both Foreign and Domestic

Live Online Policy Forum

People cannot be incarcerated simply because of their race or ethnic origin. However, they can be incarcerated for possessing or using a substance that other people have associated with that race or ethnic origin. Does the war on drugs provide a cover to exercise social control and containment of minorities and marginalized communities? A panel of experts explore this subject in depth and take questions from participants.

Introduction

Prohibition has not only failed in its promises but actually created additional serious and disturbing social problems throughout society. There is not less drunkenness in the Republic but more. There is not less crime, but more… . The cost of government is not smaller, but vastly greater. Respect for the law has not increased, but diminished.1

H. L. Mencken, 1925

Writing in 1925, journalist, social critic, and satirist H. L. Mencken wrote of the complete and utter failure of the U.S. government’s “noble experiment” with alcohol prohibition. In 1920, the Eighteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution banned the manufacture, sale, and transport of “intoxicating liquors” within the United States. Proponents of the amendment hailed the new law as a cure for myriad social ills. Eliminating alcohol consumption would, they argued, reduce crime and corruption and lower the tax burden created by prisons and poorhouses. Moreover, they contended, Prohibition would improve the health of the American public and prevent the disintegration of families.

Despite these noble intentions, alcohol prohibition was a failure on all fronts. Although alcohol consumption sharply decreased at the beginning of Prohibition, it quickly rebounded. Within a few years, alcohol consumption was between 60 and 70 percent of its pre-Prohibition level.2 The alcohol produced under Prohibition varied greatly in potency and quality, leading to disastrous health outcomes including deaths related to alcohol poisoning and overdoses. Barred from buying legal alcohol, many former alcohol users switched to substances such as opium, cocaine, and other dangerous drugs.3 Criminal syndicates formed to manufacture and distribute illegal liquors, crime increased, and corruption flourished. In light of these failures, the Eighteenth Amendment was eventually repealed in 1933.4

Few today would argue that alcohol prohibition was a wise policy. Even those who largely oppose alcohol consumption recognize the failure of the Eighteenth Amendment. Most would view Mencken’s commentary as obvious. But his words regarding alcohol prohibition are just as relevant today as nearly a century ago.

While alcohol prohibition may have been one of the first blanket bans on a substance in the United States, it certainly was not the last. In the early 1970s, President Richard Nixon declared a “war on drugs” in the United States. As a result, state and local authorities, the federal government, and even the U.S. military expanded their efforts to combat illicit drugs. Today, the War on Drugs is sometimes viewed as benign. With some states legalizing medicinal marijuana, others decriminalizing possession, and four states legalizing recreational marijuana, it is easy to forget that the drug war continues to have serious consequences.

In 1980, for example, 580,900 people were arrested on drug-related charges in the United States. By 2014, that number had increased to 1,561,231. More than 700,000 of these arrests in 2014 were related to marijuana. In fact, nearly half of the 186,000 people serving time in federal prisons in the United States are incarcerated on drug-related charges.5

The penalties for violating U.S. drug law extend beyond prison, and the specter of past drug crimes can haunt individuals for years. Approximately 50,000–60,000 students are denied financial aid every year due to past drug convictions.6 In addition, those who violate drug laws are penalized throughout their working careers in terms of limited job opportunities. Many employers, both private and public, will not hire individuals with prior drug offenses. This has particularly strong implications for minorities and other historically disadvantaged groups, who are incarcerated more frequently on drug charges. Blacks and Hispanics, for example, are much more likely than their white counterparts to be arrested for drug crimes and raided by police, even though the groups use and sell drugs at similar rates.7

The monetary cost of U.S. domestic drug policy is equally remarkable. Since the War on Drugs began more than 40 years ago, the U.S. government has spent more than $1 trillion on interdiction policies. Spending on the war continues to cost U.S. taxpayers more than $51 billion annually.8

While the domestic impact of the War on Drugs is profound, its consequences do not stop at the border. American-backed anti-drug operations in Mexico, for example, have resulted in some of the bloodiest years in Mexican history.9 In fact, since former Mexican president Felipe Calderón began using the military to fight cartels, more than 85,000 people have been killed.10 Efforts by the U.S. government to eradicate opium cultivation in Afghanistan have not only failed to reduce global supply but have also empowered and funded the Taliban.11

The U.S. War on Drugs, like the ill-fated war on alcohol of the early 20th century, is a prime example of disastrous policy, naked self-interest, and repeated ignorance on the part of elected officials and other policymakers. From its inception, the drug war has repeatedly led to waste, fraud, corruption, violence, and death. With many states moving toward legalization or decriminalization of some substances, and other nations moving to legalize drugs altogether, rethinking America’s drug policy is long overdue.

In this analysis we review the economics of drug prohibition, a cornerstone of U.S. policy for more than a century. Domestically, we focus on how prohibition affects health, crime, corruption, and violence. Internationally, we assess how prohibition affects U.S. foreign policy goals in Afghanistan. Our purpose is to demonstrate general insights about the economics of prohibition and to illustrate the devastating consequences of ignoring these insights.

The Economics of Prohibition

Just as proponents of alcohol prohibition claimed that alcohol causes a variety social ills, advocates of U.S. drug policy argue that drug use and trafficking harm public health, decrease societal wealth, increase unemployment, promote crime, corrupt law enforcement and other elected officials, and spread disease.12 Combating these alleged effects is the goal of the Office of National Drug Control Policy, whose “National Drug Control Strategy for 2015” annual report stated the following:

Illicit drug use is a public health issue that jeopardizes not only our well-being, but also the progress we have made in strengthening our economy—contributing to addiction, disease, lower student academic performance, crime, unemployment, and lost productivity.13

In addition, U.S. policymakers view prohibition as a means to reduce drug-related violence and gang activity, as well as to dismantle powerful drug cartels abroad. The “National Drug Control Strategy for 2015” says that

U.S. Federal agencies and partner nations [in drug interdiction operations] … disrupt, pull apart, and exploit the vulnerabilities of criminal organizations and the networks that are responsible for drug trafficking and money laundering… . [These policies] degrade the capacity of the cartels to operate efficiently, destabilize their organizations, and create additional opportunities to disrupt their trafficking organizations.14

If we take the goals stated by public officials and prohibition proponents as sincere, the question is whether or not current drug policies achieve these goals.

To this end, economic thinking offers valuable insight by examining how drug prohibition alters the incentives faced by individuals on both the supply and demand sides of the illicit drug market. In turn, this analysis allows us to trace the chain of consequences associated with drug prohibition.

Proponents of drug prohibition argue that by banning certain substances, they can reduce or eliminate both the demand and the supply for drugs, thereby significantly reducing or even eradicating the drug market. What these arguments fail to appreciate, however, is that making markets illegal fails to reduce, much less eliminate, the market for drugs. Instead, these mandates mainly push the market for drugs into underground black markets.

In addition, prohibition acts as a “tax” on sellers in the drug market. Would-be and current drug vendors must now incorporate fines, possible prison time, and the cost of evading capture into their business models.15 This tax drives higher-cost sellers (i.e., those unwilling or unable to incur these additional costs) out of the market.

Such a change in the drug market does align with the goals of prohibition. If sellers are pushed out of the market, this limits the supply of drugs and raises prices.16 These higher prices, in turn, reduce the quantity of drugs demanded. However, these higher prices and the changes in the market structure caused by prohibition generate unintended consequences, ones that work against prohibition’s stated goals.

Prohibition, Tainted Drugs, Illness, and Overdose

The first consequence of drug prohibition is more overdoses and drug-related illness. This is perhaps best illustrated with an example comparing how information is transferred when a drug is legal versus how it is transferred when a drug is illegal. Consider, for instance, a mislabeled or impure version of a legal, over-the-counter medication. Once a consumer becomes ill or overdoses on this medication, this information is reported, collected, and analyzed by relevant institutions. In addition, information about product quality, or lack thereof, is relayed through other channels, including media outlets, social media, and word of mouth. Consumers can therefore adjust their consumption accordingly. On the supply side, suppliers of a legal medication face the incentive to recall the product and correct the error to retain their customers and prevent legal repercussions.

These quality control mechanisms and information regarding purity are weaker or absent in a black market for drugs. First, underground markets provide less information about products and vendors because transactions occur in secret. Second, consumers in the market avoid reporting defective or impure substances because this might implicate their own law-breaking. Third, consumers of illegal drugs have no legal recourse should they purchase a substance of inferior quality, in contrast to individuals who bought tainted headache medicine or contaminated food in a legal market. On the supply side, producers and sellers of impure or tainted products face weak incentives to remove these products, knowing that buyers are unlikely to communicate with one another and unlikely to report their problems. Taken together, these factors allow more poor-quality drugs onto the market, which increases the chance of poisoning and overdose.

This is not the only way that prohibition can increase overdoses. On the supply side, prohibition leads sellers to create, transport, and sell more potent materials because prohibition’s added costs incentivize higher-potency drugs and their higher value per unit. For example, under prohibition, suppliers will tend to offer heroin compared to marijuana, since heroin is more valuable per unit (heroin sells for around $450 per gram, while marijuana sells for between $10 and $16 per gram in the United States). Likewise, drug dealers will tend to sell more potent versions of all drugs. For instance, someone selling marijuana will likely provide a product with higher concentrations of tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), the psychoactive component of marijuana, as they can earn more money per unit.17

A similar shift to more potent substances occurs on the demand side. Because prohibition raises drug prices, users seek more bang for their buck. That is, since the overall cost of obtaining drugs is higher, more potent drugs look relatively cheaper than weak drugs. If we assume that drug users rationally respond to risk and look to maximize their satisfaction or high from every dollar spent, this has three important implications.

First, users will likely switch from lower potency to higher potency within a given type of drug (for example, from marijuana with lower to higher concentrations of THC). Second, users may switch from low-potency drugs to harder drugs (such as from marijuana to cocaine). Third, users are likely to employ ingestion methods that increase the effectiveness of drugs (such as injecting rather than smoking a drug). Taken together, these information and potency effects mean that prohibition likely increases drug overdoses.

Prohibition and Drug-Related Disease

By raising drug prices, which pushes people toward harder drugs, prohibition increases disease transmission. As mentioned above, higher prices encourage more intense methods of use, such as injection. Law enforcement’s desire to promote prohibition generates restrictions on legal needles and syringes. In many states, it is illegal to buy and sell needles and syringes without a prescription. These two effects combine to encourage the reuse and sharing of dirty needles. (Repeated use of needles even by the same individual is unsafe. Needles dull with each use and may break off under the skin, thus causing infections or other problems.) The sharing of needles drastically increases the risk of transmitting blood-borne diseases such as HIV/AIDS and hepatitis.

Prohibition and Violence

Proponents of prohibition claim that banning the manufacture, sale, and use of drugs will reduce drug-related violence. This claim rests on the assumption that drug use leads to violence. But violence in drug markets may instead result from the institutional context created by prohibition.

When drugs are illegal, users cannot use formal legal channels to resolve disputes or seek legitimate protection for their business transactions. Neither buyers nor sellers in the illicit drug trade will turn to the police or other legal dispute-resolution mechanisms. Instead, individuals must solve their own problems, which often means they use violence to solve issues as opposed to more peaceful means of legal dispute resolution.

In addition to pushing individuals in the drug trade toward violence, prohibition means that those involved in the drug market are automatically criminals. This lowers the cost of committing a subsequent crime, such as assaulting a rival drug dealer, relative to a scenario in which drugs are legal. Moreover, prohibition may increase the benefits of using violence. By gaining a reputation for using violence, those involved in the drug trade may exert more effective control over the market. One result is that those with a comparative advantage in violence and criminality will be attracted to the market for drugs since these skills are necessary for long-term success.

Taken together, the lack of legal channels combined with automatic criminalization lowers the cost of engaging in criminal activity and increases the benefit of using violence. It follows that the prohibition of drugs may be the primary cause of crime in the drug market, not the physical effects of use.18

Increased violence in the drug market may generate additional unintended consequences. As a result of violent drug interactions, police are more likely to adopt more intense techniques and stronger equipment. As these practices become ingrained in everyday policing, citizens outside the illicit drug market will also be affected. Furthermore, prohibition means police are granted increased power over the lives of citizens. Absent the appropriate checks, these changes may disproportionately impact particular groups. The disproportionate number of black and Hispanic individuals incarcerated in the criminal justice system, for instance, has led to protests and social movements, such as Black Lives Matter.

Prohibition and Cartels

Proponents of prohibition argue that these policies disrupt and dismantle drug cartels. In practice, however, prohibition appears to promote cartelization of the drug industry. Recall that drug prohibition keeps some suppliers out of the drug market—those unwilling or unable to take the risks associated with operating in an illicit industry. Those individuals and groups that remain are those more comfortable with using violence and engaging in illicit activity. In a legal market for drugs, not only would the costs and benefits of using violence change (violence would be less attractive), but new entrants could more easily penetrate the market. Over time, monopoly power would be eroded as in other competitive markets. As such, cartels would be unlikely to form and would be extremely difficult, if not impossible, to maintain.

Under prohibition, however, the cost of maintaining a monopoly is reduced, as government policies effectively drive out would-be competitors, making it easier for cartels to form and maintain their dominant market position. Moreover, these effects are self-perpetuating. Under a cartelized market, monopoly power leads to an increase in prices, which further increases the benefits to dominant producers using violence to maintain their market position. Indeed, the rise of cartels in the drug industry is remarkably well documented, with researchers arguing that “cartelization in the drug trade appears to exist at every stage of production.”19 Examples abound: Chinese opium gangs dominated the opium trade during early prohibition efforts. Colombian drug cartels controlled the flow of cocaine into the United States throughout the 1980s and 1990s. Today, Mexican drug cartels provide a variety of drugs—including marijuana, cocaine, and methamphetamine—to U.S. markets. In each of these cases, the violence associated with the drug markets has been substantial.

Prohibition and Corruption

The cartelization of the drug industry under prohibition helps give rise to yet another unintended consequence: the corruption of public officials and civil servants. The illegal nature of the market, desire to avoid capture, and potentially high profit margins create a strong incentive for those involved in the drug trade to avoid being captured and punished. As a result, these individuals are more likely to attempt to bribe public officials (including police officers, military personnel, judges, and other elected officials) involved in drug interdiction.20 While some officials may take these bribes willingly, the violent tendencies of people involved in the drug trade provides additional motivation for public officials to accept bribes. Indeed, we observe that those who refuse to take bribes are often threatened with violence against their families. Consider Mexico, in which lawyer and Mexican senator Arturo Zamora Jiménez notes that “Enforcing current laws to prosecute criminals is difficult because members of the cartels have infiltrated and corrupted the law enforcement organizations that are supposed to prosecute them, such as the Office of the Attorney General.”21

Consequences of the War on Drugs: Evidence from the United States

Until the turn of the 20th century, currently outlawed drugs such as marijuana, heroin, and cocaine were legal under federal and virtually all state laws. In 1906, Congress implemented the first restrictions on the sale and use of some substances, including cannabis, morphine, cocaine, and heroin, with the Pure Food and Drug Act, labeling many substances as addictive or dangerous.22 In 1914, the Harrison Narcotics Act further regulated the market for opiates, cocaine, and other substances, resulting in a surge in drug offense charges. By 1938, more than 25,000 American doctors had been arraigned on narcotics charges; some 3,000 served time in prison.23

While these early laws are important for understanding current drug restrictions, the strictest and most relevant polices began in the 1970s when Nixon declared drugs “public enemy number one.”24 In 1970, Congress passed the Comprehensive Drug Abuse Prevention and Control Act (CDAPC), which brought many separate federal mandates under a single law and established a schedule of controlled substances. In 1972, the House voted unanimously to authorize a “$1 billion, three-year federal attack on drug abuse.”25 The Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) began operations the following year, absorbing other agencies, including the Bureau of Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs (BNDD) and the Office of Drug Abuse Law Enforcement (ODALE). The DEA was tasked with enforcing all federal drug laws, as well as coordinating broader drug interdiction activities.26 Under the direction of the DEA, what is now known as the War on Drugs quickly expanded in scale and scope.

Overdose Deaths and Drug-Related Illness in the United States

Under prohibition, poor information quality and flow, combined with potency effects on both sides of the market, would predict an increase in drug-related deaths. This is precisely what we observe. In 1971, two years before the creation of the DEA, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported that slightly more than 1 death per 100,000 people in the United States was related to drug overdose. This figure rose to 3.4 deaths per 100,000 people by 1990 (see Figure 1). By 2008, there were 12 overdose deaths per 100,000 people.27

Figure 1

Overdose Deaths per 100,000 People, 1980–2008

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “Data Brief 81: Drug Poisoning Deaths in the United States, 1980–2008,” https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db81_tables.pdf#4.

These numbers have continued to climb. According to the CDC, more than 47,000 overdose deaths occurred in the United States in 2014, representing 14.7 deaths per every 100,000 people in the United States, the most overdose deaths ever recorded in the country. Between 2000 and 2014, more people in the United States died from drug overdoses than from car crashes.28

As economic reasoning predicts, the majority of these deaths are related to consumption of more potent drugs. In 2014, for instance, 61 percent of all overdose deaths were caused by opioids. The rate of opioid overdoses increased significantly in the first 15 years of the new millennium. Between 2013 and 2014, overdose deaths involving synthetic opioids nearly doubled, and the rate of all opioid overdoses has more than tripled since 2000.29

The spread of drug-related disease in the United States has also seen a sharp increase since the launch of the War on Drugs. In 2000, nearly 60 percent of all new hepatitis C infections and 17 percent of hepatitis B infections occurred in drug users.30 While the majority of new HIV/AIDS cases result from unprotected sexual encounters, 6 percent of all new infections result from intravenous drug use.31 As of 2012, an estimated 91,000 Americans live with HIV/AIDS acquired via drug use.32

Violence in the U.S. Drug Market

Just as overdose deaths and drug-related illnesses increase under drug prohibition, so, too, does violence related to the market for drugs. In one study of New York City homicides, researchers found that while only 7.5 percent of murders committed during the period analyzed were related to the physical effects of drug use, 40 percent were related to the “exigencies of the illicit market system.”33

Other studies over the past four decades have reached similar findings. A 1998 study found that increased drug enforcement was positively and significantly associated with increases in violent crime.34 Another study from the same period found that variance in drug enforcement accounted for more than half of the variation in homicide rates between 1900 and 1995, with more drug enforcement correlating with more violence.35 The International Centre for Science in Drug Policy conducted an extensive survey of the literature related to violence in the drug market, finding overwhelming evidence that prohibition has led to an increase in crime as opposed to a decrease.36

Cartelization of the Drug Industry

Just as alcohol prohibition gave rise to the American Mafia, the early prohibition of opium and other drugs in the late 1800s and early 1900s fostered the formation of Chinese drug gangs. From the 1890s to the 1930s, for example, the Tong Wars took place in New York’s Chinatown. These tongs, or fraternal organizations, acted as gangs, and they profiteered from opium, gambling, and prostitution, using violent tactics ranging from stabbings to bombings.37 The tendency of prohibition policies to foster organized crime is not limited to these historical cases.

The modern War on Drugs promoted the creation and strengthening of violent cartels. Colombian economist Eduardo Sarmiento Palacio, for example, argued that the U.S. War on Drugs led directly to the rise of Colombian drug cartels.38 The best illustration of the cartel problem can be observed in Mexico and along the southern U.S. border.39 As a result of frequent crackdowns on drug sellers in the United States, Mexican drug cartels have seized the opportunity to export hard drugs such as heroin, cocaine, and methamphetamine.40 The incentives facing these drug syndicates are clear: consider that a kilo of raw opium produced in Mexico sells for about $1,500 there, but will sell for between $40,000 and $50,000 in the United States.41 Likewise, a kilo of cocaine costs around $12,000 in Mexico, but will fetch around $27,000 in the United States. There is further evidence that cartel-controlled operations are replacing domestic drug producers. According to the DEA, methamphetamine lab busts have fallen from almost 24,000 in 2004 to 11,573 in 2013. At the same time, however, border states have witnessed a marked spike in methamphetamine seizures as Mexican “super labs” ship drugs across the border.42

These cartels have helped fuel violence within both the United States and Mexico. Since 2006, more than 85,000 people in Mexico have been killed as a result of the drug trade.43 In the United States, Mexico’s Sinaloa Cartel has effectively taken control of many markets, such as the market for heroin in New York City, and has overtaken traffickers from Colombia and Afghanistan. According to the DEA, about 50 percent of all heroin sold in the United States is produced in Mexico. However, almost all heroin sold in the United States, regardless of its country of origin, is supplied by Mexican cartels. It is estimated that Mexican traffickers operate in more than 1,200 U.S. cities.44

Drugs and Corruption in the United States

Corruption in the United States related to the drug war is well documented. A 2009 report from the Associated Press found that “U.S. law officers who work the border are being charged with criminal corruption in numbers not seen before, as drug and immigrant smugglers use money and sometimes sex to buy protection.”45 In July 2016, a jail guard in Alabama was charged with trying to smuggle drugs into the jail by concealing them inside a Bible.46 That same month, a deputy with the Cherokee County Sheriff’s Office in Georgia was charged with stealing narcotics from the station’s evidence locker.47 Four days before the deputy was charged, a former jail guard in Philadelphia was sentenced to four years in federal prison for selling drugs to inmates.48 Just a week prior to this sentencing, two Detroit police officers were convicted of conspiring to steal drugs and money seized during police raids instead of reporting them as evidence. One officer was sentenced to 12 years and 11 months in prison, while the other was sentenced to 9 years.49

One particularly insidious component of the War on Drugs is civil asset forfeiture. This policy allows police, prosecutors, and other law enforcement agencies to seize assets (such as cash, cars, and homes) used or thought to be used in commission of a drug crime. In many cases, a portion of the confiscated assets flows to the budgets of the confiscating agency. In Philadelphia, for example, authorities have seized more than $64 million in assets over a 10-year period, with $25 million of these assets funding the salaries of public officials. In Hunt County, Texas, some law enforcement officials received $26,000 for their efforts in seizing assets related to the War on Drugs.50

The perverse incentives created by civil forfeiture are obvious. If an agency’s budget or an individual’s pay is directly tied to forfeited assets, then those agencies and individuals will seek out opportunities to seize assets. This makes corruption more profitable and more likely. In many cases, the payoffs can be large. In 2011, for example, Virginia state police kept 80 percent of $28,000 confiscated from the car of a church secretary.51 Because he was traveling with such a large amount of cash, he was suspected of being involved in the drug trade. However, the man was transporting cash needed to buy new property for the church. In a similar scenario in Houston, one couple was threatened with jail and the removal of their children by the state if they refused to turn over the cash in their car to the local District Attorney’s Office. They had been planning to use the money to buy a car.52 In total, the Department of Justice’s Asset Forfeiture Fund confiscated nearly $94 million in assets during 1986, its second year of operations. By 2011, this number had ballooned to approximately $1.8 billion. State and local seizures have followed similar trends.53

Police Militarization and the War on Drugs

The standard unintended consequences predicted by the economics of prohibition are not the only problems faced by the United States as a result of its drug policy. In addition, the drug war has engendered racial tensions and substantial changes in a variety of political, social, and other institutions, particularly policing.

The first drug prohibition laws were enforced by preexisting government agencies, specifically the Bureau of Internal Revenue. Today’s drug laws are imposed by a cadre of federal agencies including the DEA, the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF), the Federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP), the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), the CDC, and the U.S. Coast Guard (USCG). In addition, Customs and Border Protection (CBP), Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), the National Drug Intelligence Center (NDIC), the Office of National Drug Control Policy (ONDCP), the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency (OJJDP), and the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) also work to carry out the War on Drugs.

Federal agencies are not the exclusive enforcers of drug policy. In fact, the enhanced weaponry and tactics so frequently seen as hallmarks of modern U.S. drug policy are often carried out not by the ATF or FBI, but by state and local law enforcement. Historically, the United States has attempted, in theory if not in practice, to separate the functions of the police and the military.54 State and local law enforcement are tasked with upholding domestic laws and protecting the rights of all citizens, both innocent bystanders and those accused of committing a crime. Military personnel, meanwhile, engage with external threats to the United States and its citizens.55 Although a variety of factors blurred these distinctions and eroded the laws intended to enforce this distinction, U.S. drug policies have been integral in the militarization of U.S. domestic police, in which domestic law enforcement officials have acquired military weapons and training and have used military tactics in their normal operations.56

The War on Drugs is particularly important from the perspective of police militarization in that this “war” differs from other conflicts throughout U.S. history. In WWI, WWII, and Vietnam, for example, enemy combatants were clearly definable and external to the United States. The “enemies” in the War on Drugs however, consist not only of external threats (such as the Latin American drug cartels), but also American citizens on domestic soil. This addition of a domestic “enemy” links a variety of government agencies, including state and local law enforcement, to the broader missions of the U.S. federal government. Domestic law enforcement, recognizing that linking their missions with the drug war could increase their discretionary budgets and number of personnel, would benefit from joining the operations. Federal authorities would have additional personnel to fulfill their goals. The War on Drugs has created a domestic battle zone where U.S. citizens are viewed as potential enemies to be defeated by an array of government agencies working in conjunction to enforce prohibition.

The militarization of U.S. domestic police is readily apparent from the legislation passed since the early 1970s. As noted above, those involved in any aspect of the drug market, interdiction included, are now more likely to encounter individuals with a comparative advantage in violence and face an increased frequency of violent actions. For police, this provides a strong incentive to adopt more forceful tactics.

One of the best examples of how the drug war has blurred the line between police and military is the Military Cooperation with Law Enforcement Act (MCLEA) of 1981. The MCLEA allowed the Department of Defense (DOD) to share information with local police departments and to participate in local counter-drug operations. Plus, the Act allowed DOD to transfer excess military equipment and other materials to domestic law enforcement for the purposes of combating illegal drugs.57

Other programs provided further opportunities for police to adopt military tactics and equipment in the name of combating drugs. For instance, the National Defense Authorization Act of 1990 (NDAA) created the 1208 Program. This program, building on the MCLEA, authorized additional transfers of military equipment to state agencies to combat drugs. In 1997, Program 1033 subsumed and expanded upon Program 1208. This incarnation of the program allowed the DOD to transfer aircraft, armor, riot gear, surveillance equipment, and weapons to state agencies. Armored vehicles were made available for “bona fide law enforcement purposes that assist in their arrest and apprehension mission.”58

The 1122 Program has channeled additional weapons and tactical gear to domestic police by providing state and local law enforcement with new military equipment. Once again, this program started with the goal of using domestic law enforcement to combat illegal drugs. According to the program’s manual, it “affords state and local governments the opportunity to maximize their use of taxpayer dollars by taking advantage of the purchasing power of the Federal Government.” Any “unit of local government” is eligible, meaning that any “city, county, township, town, borough, parish, village, or other general purpose political subdivision of a State” could apply to receive the weapons.59

The use of these programs has expanded immensely since their creation. In the first three years following the MCLEA’s passage, for example, the DOD granted nearly 10,000 requests from state and local law enforcement.60 According to the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), more than $4.3 billion in materials has been transferred through Program 1033 alone. The program involves more the 17,000 agencies. The value of the property transferred from the federal government and military to state and local authorities was about $1 million in 1990. By 1995, this number had climbed to $324 million. As of 2013, nearly $450 million in equipment was transferred on an annual basis.61

The breakdown of the distinction between local and military forces is also evident in the programs offered by federal agencies such as the DEA and FBI. The DEA, for example, was a single bureau in the 1970s. Now the agency works with more than 350 state and local law enforcement agencies, providing specialized training in drug interdiction. The agency also manages more than 380 task forces throughout the country, which coordinate information and resource sharing among state, local, and federal agencies.62

The impact of these programs and relationships is not trivial. Equipment and tactics once exclusively used by military or federal agencies abroad are now commonly used by state and local law enforcement against civilians.

Consider “no-knock raids,” which involve law enforcement personnel entering a property without first notifying residents by announcing their presence or intention to enter. This style of raid, once used exclusively by the military, is now common practice by domestic law enforcement. Hundreds of botched no-knock raids have been documented throughout the country.63 In some cases, police raided the wrong residence or killed or injured innocent civilians or nonviolent offenders. In other cases, police officers have been injured executing the raids. Moreover, these raids are frequently conducted by Special Weapons and Tactics (SWAT) teams or Police Paramilitary Units (PPUs), groups of domestic law enforcement personnel with specialized military equipment (like that obtained through the 1033 and 1122 programs) and training. The SWAT teams and PPUs are deliberately modeled after specialized military teams.64

The number of no-knock raids has increased dramatically as a result of the War of Drugs (and the War on Terror). In the mid-1980s, approximately 20 percent of small towns employed a PPU or SWAT team. Eighty percent of small-town police departments now have a SWAT team.65 By 2000, almost 90 percent of police departments serving populations of 50,000 or more people had some kind of PPU. Approximately 3,000 SWAT deployments occurred in 1980. By the early 2000s, SWAT teams saw about 45,000 deployments a year.66 Data from 2005 indicates that SWAT teams were deployed 50,000 to 60,000 times that year.67 Current estimates place the number of deployments as high as 80,000 annually.68

The War on Drugs and Racial Bias in the United States

The unintended consequences of the War on Drugs do not affect all groups equally. In the United States, it is well documented that these policies disproportionately impact minority communities, particularly blacks and Hispanics. Attorney and legal scholar Graham Boyd has referred to the drug war as the “new Jim Crow.”69

Recent reports indicate that this may not be an accident. In early 2016, Harper’s magazine published part of a 1994 interview in which former Nixon domestic policy chief, John Ehrlichman, stated that

You want to know what this [the War on Drugs] was really all about? The Nixon campaign in 1968, and the Nixon White House after that, had two enemies: the antiwar left and black people. You understand what I’m saying? We knew we couldn’t make it illegal to be either against the war or black, but by getting the public to associate hippies with marijuana and blacks with heroin, and then criminalizing both heavily, we could disrupt those communities. We could arrest their leaders, raid their homes, break up their meetings, and vilify them night after night on the evening news. Did we know we were lying about the drugs? Of course we did.70

Ehrlichman’s children have doubted the veracity of the quote, but the journalist is adamant that these statements are genuine. Regardless of the original intention, however, the effects of the drug war on minority groups are undeniable.

Black individuals, for example, make up only 12 percent of the U.S. population as a whole, but they represent 62 percent of the drug offenders sent to state prisons. Black men are sent to state prisons on drug charges at 13 times the rate of white men.71 One study of marijuana arrests in Virginia between 2003 and 2013 found that, despite constituting only 20 percent of the state’s population and using marijuana at similar rates to their white counterparts, arrests of blacks more than doubled while arrest rates for whites increased by 44 percent.72

SWAT raids are also much more likely to be carried out against minority groups. The ACLU found that nearly 50 percent of all SWAT raids between 2011 and 2012 were conducted against black and Hispanic individuals, while only 20 percent of raids involved white suspects (the other 30 percent is unknown or other).73 In many places throughout the country, minority groups are much more likely than their white counterparts to be impacted by SWAT raids. In Allentown, Pennsylvania, for example, Latinos are 29 times more likely to be targeted by a SWAT raid than whites, while blacks are 23 times more likely to be targeted than whites. Blacks are 37 times more likely to be the victim of a SWAT raid in Huntington, West Virginia, than their white counterparts. Blacks in Ogden, Utah, are 39 times more likely to be subjected to a SWAT raid, and blacks in Burlington, North Carolina, are 47 times more likely to be targeted compared to whites.

The overrepresentation of minorities in drug offenses and the criminal justice system has additional implications. A single conviction for drug possession may render some students automatically ineligible for federal student aid, including grants, loans, or work-study. How long a student is ineligible depends on the type of offense, but some individuals may be permanently banned from federal education assistance.74 An estimated 20,000 students annually lose out on Pell Grants due to drug offenses. Another 30,000 to 40,000 are denied student loans.75 As minority individuals are more likely to be arrested for drug-related offenses, they are consequently more likely to be denied educational assistance and the opportunity to invest in their human capital.

A felony drug charge (which, in some states, requires only three-quarters of an ounce of marijuana) can also cause an individual to lose eligibility to work for the federal government; enlist in the U.S. Armed Forces; obtain an import, customs, or other license; or obtain a passport.76 Many private-sector job applications require criminal background checks and the disclosure of felony convictions, preventing individuals convicted of drug offenses from obtaining gainful employment. Given the rate at which minorities are arrested for crime, this has immense implications for the long-term prosperity of both individuals and broader communities.

The War on Drugs Abroad

The adverse consequences of the U.S. government’s War on Drugs do not stop at the borders; the U.S. government has likewise set its sights on the international drug market. By combating illicit drugs abroad, the U.S. government hopes to curtail the flow and subsequent sale and use of drugs in the United States. Moreover, by assisting foreign governments with drug interdiction, the U.S. government aims to maintain regional balances, disrupt international criminal syndicates that threaten domestic and international security, and push foreign entities to undertake policies that align with U.S. interests.

International drug policy is not a new arena for the United States. In 1909, the International Opium Commission, also known as the Shanghai Opium Commission, convened to discuss opium production in Asia. The Commission and the policies surrounding it included a variety of countries, including the United States, Great Britain, China, India, Hong Kong, Singapore, and Persia (Iran).77 Modern international efforts hinge on three key United Nations treaties—the 1961 Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs, the 1971 Convention on Psychotropic Substances, and the 1988 Convention against Illegal Traffic in Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances. Following in Nixon’s footsteps, President Ronald Reagan issued National Security Decision Directive No. 221, “Narcotics and National Security,” which placed international drug interdiction efforts at the forefront of U.S. drug policy.78

Successive administrations have continued this trend. In 2010, for example, both the Mexican and United States governments agreed to the Mérida Initiative, which aims to combat drugs and illegal trafficking along the U.S.–Mexican border and throughout Central America. Between 2008 and 2014, Congress authorized payments of $2.4 billion to Mexico for the Mérida Initiative.

Around the same time, the Central American Citizen Security Partnership and the Central American Security Initiative were created as the U.S. government reported that 80 percent of U.S.-bound cocaine (via the Mexican border) had, at some point, been in Belize, Costa Rica, Honduras, El Salvador, or Brazil. Between 2008 and 2014, Congress allocated $803.6 million in regional assistance to these programs. The Caribbean Basin Security Initiative (CBSI), launched in 2010 following a meeting between the United States and 15 Caribbean nations, sought to reduce drug trafficking to the United States, Europe, and Africa. Congress appropriated $327 million in international assistance to the Initiative between 2010 and 2014.

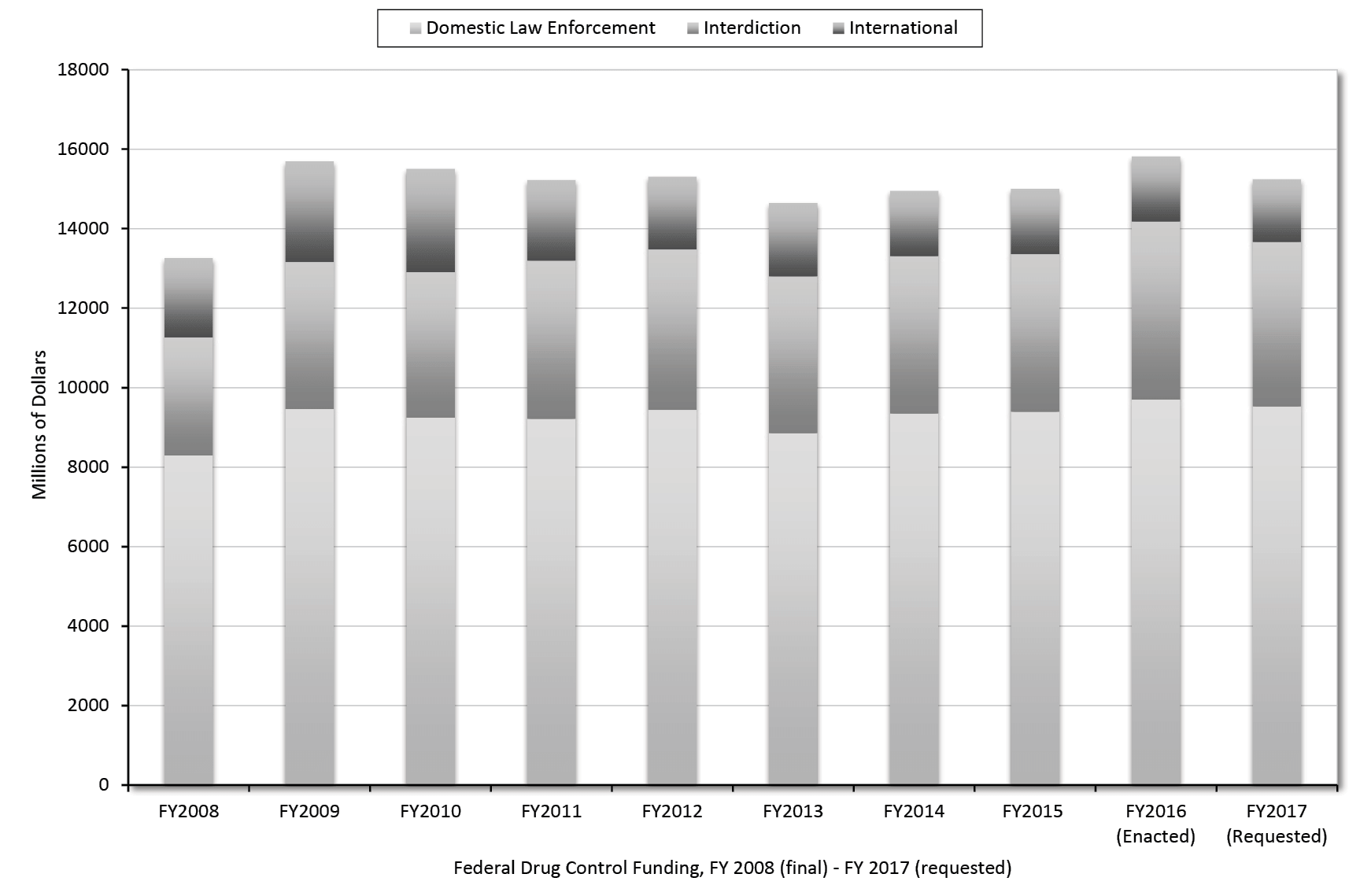

In 2011, the U.S. State Department spearheaded the West African Cooperation Security Initiative (WACSI), another counter-drug operation, with approximately $60 million in support.79 Figure 2 shows these U.S. counter-drug expenditures, as well as others, and illustrates federal expenditure on domestic drug operations, international initiatives, and interdiction efforts, or the attempts to prevent the transport of drugs from one geographic location to another.80

Figure 2

Federal Drug Control Funding, FY2008 (final)—FY2017 (requested), in Millions of Dollars

Source: Office of National Drug Control Policy, “National Drug Control Budget FY 2017 Funding Highlights,” February 2016, https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/sites/default/files/ondcp/press-releases/fy_2017_budget_highlights.pdf.

Prohibition is the motivation for all of these programs. As evidenced by the outcomes in the United States, one may rightfully expect these international policies to have led to a variety of unintended consequences. These consequences are illustrated clearly in the ongoing U.S. occupation of Afghanistan and associated efforts to eradicate opium cultivation.

The War on Drugs in Afghanistan

The economics of prohibition is central to understanding the failed U.S. effort to build stable political, economic, legal, and social institutions abroad. By neglecting the insights of economics, the U.S. government has continually adopted policies that have been counterproductive to its broader stated goals, including major U.S. initiatives like nation building and counterterrorism.

Since the U.S. invasion of Afghanistan in 2001, the country has experienced three phases of U.S.-imposed drug policy.81 Each phase involved drug prohibition, particularly of opium and the poppy from which it is derived.82 In the earliest stages of the occupation, U.S. forces supported national prohibition but did not engage in the implementation of these programs. In fact, U.S. forces worked with the local warlords who largely controlled the country’s drug trade. In exchange for assistance with fighting the Taliban, the U.S. turned a blind eye to trafficking. Following this phase, the U.S. shifted toward zero tolerance of opium and other illegal drugs. The U.S. forces not only sought complete eradication, but actively engaged in combating drugs within the country. In the third and most recent phase, policy shifted once again to focus on providing those in the drug industry “alternative livelihoods,” but the U.S. government continues to pursue policies of complete eradication by financing local governments to carry out eradication efforts.

The U.S. drug policies in Afghanistan, like other international initiatives, purport not only to reduce the drug trade in the United States, but also to achieve other policy goals. In December 2004, for example, Lieutenant General David W. Barno, the top U.S. commander in Afghanistan, stated that the War on Drugs was one of three wars necessary to win the War on Terror.83 In particular, counter-drug policies in Afghanistan are viewed by many in the U.S. government as necessary in the ongoing battle against al Qaeda and Taliban insurgents, as these groups derive significant revenue from the illicit drug trade. Thomas Schweich, the U.S. State Department’s coordinator for counter-narcotics in Afghanistan, stated that “It’s all one issue. It’s no longer just a drug problem. It’s an economic problem, a political problem and a security problem.”84

Afghanistan has seen a massive inflow of U.S. taxpayer dollars aimed at eradicating the drug trade. The Department of Defense, for example, more than tripled its operating budget for counter-narcotics in Afghanistan from $72 million in 2004 to $225 million in 2005. Most of these funds were used to support joint Afghan and American anti-drug efforts.85 The Department of Justice, Department of State, DOD, and DEA have also escalated their operations in Afghanistan. After reopening its Kabul office in 2003, the DEA steadily expanded its presence from 13 to 95 offices.86 The DEA’s operating budget in Afghanistan quadrupled from $3.7 million in 2004 to $16.8 million in 2005, and increased still further, to $40.6 million, in 2008.87 According to General John Sopko, the Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction, the U.S. government has, in total, spent $8.4 billion there on counternarcotic efforts.88

Despite military efforts and billions of dollars spent, the U.S. government has little to show for its efforts. Counter-drug policies in Afghanistan have not curtailed the drug market domestically and have been counterproductive to other U.S. policy goals. In fact, cultivation of opium poppy nearly tripled between 2002 and 2013, from 76,000 hectares in 2002 to a record 209,000 hectares.89 According to the United Nations, Afghanistan now produces some 80 percent of the world’s illicit opium.90 The opium economy in Afghanistan is more concentrated in the hands of the Taliban than ever before.

Cartelization and the Taliban

The U.S. drug policies in Afghanistan have cartelized the drug trade and strengthened the Taliban insurgency in several ways. First, eradication efforts acted as a tax on opium producers by imposing additional costs such as fines, imprisonment, and even death. These higher costs tend to force out smaller producers, leaving larger producers to dominate the market.

Second, local leaders have faced strong incentives to manipulate eradication efforts to target smaller producers.91 Without the resources and connections to avoid eradication efforts, smaller producers made easy targets. And by pursuing small producers, local leaders and other officials could show they were doing something to combat opium production. The result was that large producers thrived. These same producers became increasingly integrated with the Taliban, who developed a cartel over the country’s opium production.

The driving force behind this integration was the entrepreneurial alertness of the Taliban. Seeing the chance for profit as a result of the national ban on drugs, the Taliban became a one-stop shop for all the needs of local opium poppy farmers. According to one report, the Taliban became “increasingly engrossed in both the upstream and downstream sides of the heroin and opium trade—encouraging farmers to plant poppies, lending them seed money, buying the crop of sticky opium paste in the field, refining it into exportable opium and heroin, and finally transporting it to Pakistan and Iran, often in old Toyotas to avoid detection.”92 Moreover, in response to U.S. policy, the Taliban also began to offer protection in exchange for a portion of farmers’ crops or revenues.93

As a result, the opium trade in Afghanistan is a major source of revenue for the Taliban, and has generated between $200 million and $400 million annually since the Taliban’s resurgence in 2005.94 Captured Taliban fighters state that poppy production is their primary source of operational funding, including salaries, weapons, fuel, food, and explosives.95

The Criminalization of Afghan Citizens

The third consequence of U.S. drug policy in Afghanistan has been the criminalization of ordinary Afghan citizens. The opium economy is a main source of income for people throughout the country. According to the Special Inspector General for the Afghanistan Reconstruction, the nation’s drug trade employs more than 410,000 Afghan citizens full-time.96 That figure likely understates the number of Afghans working in the industry, as it does not include those involved on a part-time or seasonal basis. For many people in the country, participation in the drug economy is the only means of earning a sufficient income.

A 2013 survey conducted by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime indicated that the main reason many Afghan farmers grow opium poppies is the high price of opium, which provides increased income, improved living conditions, and the ability to afford basic food and shelter.97 One farmer, for example, explained that growing poppies was the only way to make ends meet. “[F]or the rest of our product [corn, cotton, potatoes, etc.] we have no market. We can’t export [other crops] and get a good price. We can’t even sustain our families.”98 Another farmer stated, “[W]e have to do this in order to have a better life.”99

The criminalization of thousands of Afghan citizens jeopardizes the very aims of U.S. counterterrorism policy. By labeling these individuals as criminals, and putting their livelihoods at risk, prohibition breeds disaffected citizens more likely to sympathize with terrorists.

As a result, many Afghans align themselves with the Taliban, who offer them protection from, and retaliation against, U.S. eradication efforts. That alliance is strengthened by the fact that Taliban commanders, even those operating at the village level, often receive hundreds of thousands—if not millions—of dollars in revenues collected as taxes from farmers and smugglers in the opium economy. The potential income prompted many to join the organization in hopes of improving their own livelihoods.100 NATO researchers estimate that contracted Taliban soldiers receive as much as $150 a month, a full $30 more than official police. In a country where the average annual income is less than $500, such a relatively high-paying position has obvious appeal, especially for those who are already categorized as criminals.101

Taken together, this criminalization of citizens has two undesirable effects. First, it strengthens the Taliban by pushing Afghan citizens toward the organization. Second, it undermines U.S. efforts at building a new stable government. For many Afghans, U.S. policies bring uncertainty, unemployment, and poverty, as opposed to liberty and economic prosperity.

Violence and U.S. Drug Policy in Afghanistan

The cartelization of the drug industry in Afghanistan has also increased violence. No available data exist on deaths related to drug activities, but violence in the country is correlated with opium production. For example, violence against U.S. troops peaks during the months in which the opium poppy is harvested.102 Although drug activity is not the only cause of violence, a connection appears to exist between this activity and violence against coalition forces; for example, the most violent provinces in Afghanistan, Helmand and Kandahar, are likewise the largest producers of the opium poppy.103

Although the data may not be able to establish causality, the U.S. Department of State has readily acknowledged the link between the Afghan drug trade and violence, reporting that “opium trade and the insurgency are closely related. Poppy cultivation and insurgent violence are correlated geographically.”104 Other empirical studies of the relationship between the opium trade and domestic terrorist activity in Afghanistan between 1996 and 2008 have found that “provinces that produce more opium feature higher levels of terrorist attacks and casualties due to terrorism, and that opium production is a more robust predictor of terrorism than nearly all other province features.”105 As noted above, the criminalization of hundreds of thousands of Afghan citizens further increases the likelihood of violence, as many people are drawn into the Taliban insurgency in an effort to protect their source of income.

Drugs, Corruption, and the Afghan Government

Corruption is another unintended consequence of U.S. drug policy in Afghanistan and is deeply embedded in the country’s economic, legal, social, and political institutions. A recent report by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime stated that “While corruption is seen by Afghans as one of the most urgent challenges facing their country, it seems to be increasingly embedded in social practices, with patronage and bribery being an acceptable part of day-to-day life.”106 Testifying before the U.S. Senate, retired general John Allen said that “For too long we [the U.S.] focused our attention solely on the Taliban as the existential threat to Afghanistan,” noting that compared to the problems caused by corruption, the Taliban “are an annoyance.”107 Although many U.S. officials recognize corruption as a problem in Afghanistan, many fail to recognize that U.S. drug policies have contributed to the perpetuation and entrenchment of corruption there.

Just as drug prohibition in the United States created illicit profit opportunities that otherwise would not have existed, the same dynamic is present in Afghanistan. The ban on opium and other drugs, combined with U.S. eradication efforts, means that both farmers and members of the Taliban wish to circumvent these laws. As is well documented, under regimes of prohibition, bribing elected officials, judges, police, and military involved in combating illegal drugs is one way around legal restrictions.108

Such activity is common in post-invasion Afghanistan. According to Thomas Schweich, special ambassador to Afghanistan during the Bush administration, many top Afghan officials are not only willing to turn a blind eye to drug activity, but are even complicit in the trade themselves. He notes that

Narco-traffickers were buying off hundreds of police chiefs, judges, and other officials. Narco-corruption went to the top of the Afghan government. The attorney general [of Afghanistan] … told me and other American officials that he had a list of more than 20 senior Afghan officials who were deeply corrupt—some tied to the narcotics trade. He added that President Karzai … had directed him, for political reasons, not to prosecute any of these people… . Around the same time, the United States released photos of industrial-sized poppy farms—many owned by pro-government opportunists, others owned by Taliban sympathizers. Farmers were … diverting U.S.-built irrigation canals to poppy fields.109

This corruption extends to even the smallest eradication efforts. One counter-drug initiative undertaken by the U.S. government involved offering a one-time payment to local leaders in exchange for decreasing poppy output in their provinces. While it appeared that leaders took well to the program, numerous reports found that local officials received their rewards for eradication only to use the funds to develop their own drug businesses in other parts of the country.110 The one-shot nature of the payouts created additional perverse incentives as, after receiving their reward, leaders subsequently turned a blind eye to the drug trade in exchange for a payoff from local farmers.

Corruption is also apparent at the highest levels of government. In 2007, for example, former president Hamid Karzai appointed Izzatulla Wasifi, a convicted heroin dealer, to the head of Afghanistan’s anti-corruption commission. Wasifi, in turn, appointed several known corrupt politicians as local police chiefs. It is well known that Karzai’s brother, Ahmed Wali Karzai, was intimately involved in the drug trade, overseeing one of the largest opium-producing provinces in the country.111

In 2004, Afghan security forces uncovered a large stash of heroin, seizing the drugs and the truck in which they were being transported. The commander of the unit quickly received a phone call from Ahmed Wali Karzai, asking that the vehicle and drugs be released. After another phone call from an aide to Karzai, the commander complied.112 Two years later, another truck, this one carrying 110 pounds of heroin, was apprehended near Kabul. Investigators linked the shipment to one of Ahmed Wali Karzai’s bodyguards, who was believed to be acting as an intermediary. In discussing these issues regarding the president’s brother, Afghan informant Hajji Aman Kheri stated, “It’s no secret about Wali Karzai and drugs. A lot of people in the Afghan government are involved in drug trafficking.”113

Other instances of corruption within the Afghan government abound. In 2005, for example, British forces intercepted 20,000 pounds of opium in the office of prominent Afghan governor Sher Mohammed Akhundzada, a close ally of Karzai. He was forced out of office as a result of the incident but was later appointed to the senate.114 In 2006, the nominee for the head of border protection was caught smuggling heroin. Although his appointment was withdrawn, he is now a prominent representative in the Afghan Parliament.115

While U.S. policymakers hope that corruption in Afghanistan will improve under President Ashraf Ghani, this remains to be seen. According to Transparency International’s Global Corruption Index, Afghanistan is one of the most corrupt countries on the planet, ranking 166 out of 168. According to the index, the government is perceived as easily influenced by private interests, and scored 11 out of 100 on the Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) for 2015. (Scores nearer to 100 indicate less corruption, while scores closer to zero denote high levels of corruption.) To put these numbers in context, the United States is ranked number 16 on the Global Corruption Index and scored 76 on the CPI, while North Korea is ranked at 167 (just one place below Afghanistan) and scored 8 on the CPI.116 Given that U.S. policy is unlikely to change in the foreseeable future, it remains doubtful that such improvements will materialize.

Implications for Policy

The shift in public attitudes regarding drug policy is remarkable. In 1990, 73 percent of Americans surveyed favored a mandatory death sentence for major drug traffickers. About 57 percent agreed that police should be allowed to search the residences of known drug dealers without a court order.117 Today there is wide public support for changing U.S. drug policies. A 2014 report by the Pew Research Center found that 67 percent of respondents thought that government should implement policies focused on treatment, while only 26 percent stated that prosecution should be the focus.118 When asked what substance is more harmful to a person’s health, 69 percent of respondents felt alcohol was more harmful than marijuana. Some 63 percent said that alcohol is more harmful to society, even if marijuana were to be made just as widely available.119

Just as many states began to eschew alcohol prohibition prior to the repeal of the Eighteenth Amendment, states today are taking serious steps toward relaxing some drug laws. Between 2009 and 2013, for example, 40 states took some action to ease their drug laws, lowering the penalties for possession and use, shortening mandatory minimum sentences, and removing “sentence enhancements” in which judges may automatically increase a defendant’s sentence if certain factors are present.120 As a result of these policy changes and an overall decline in crime rates, the state imprisonment rate fell from 447 prisoners per 100,000 individuals to 413 between 2007 and 2012.121

However, drug policy has not shifted across the board. Some states have recently strengthened their drug laws, and other states have relaxed some laws while strengthening others. While the state imprisonment rate has fallen, the federal imprisonment rate has increased, from 59 to 62 sentenced prisoners per 100,000 people.122 In late 2016, an application to reclassify marijuana from a Schedule I to a Schedule II drug of the Controlled Substances Act, proposed by Governors Gina Raimondo (D‑RI) and Jay Inslee (D‑NM), was never adopted. Under current law, Schedule I substances are the most restricted because they are considered to have a high potential for abuse and no legitimate medical use. This rejection cuts against previous statements by President Barack Obama and some other officials, who stated that scientific findings should drive U.S. drug policy. In fact, only 9 percent of those who use marijuana fit the criteria for dependence. To put this in perspective, approximately 15 percent of those who drink alcohol fit the criteria for dependence.123 Taking into account concerns regarding drug use by minors, Aaron Carroll, professor of the Indiana University School of Medicine, states that “After going through all the data and looking at which is more dangerous in almost any metric you would pick, pot really looks like it’s safer than alcohol.” When asked about the correlation between drugs and crime, Carroll continued, “[T]he number of crimes that are committed that have some sort of alcohol component related to them are massive—hundreds of thousands per year, if not more … [rates of violent assault are] lower in people who smoke marijuana than people who don’t.”124

What drives the continued War on Drugs is beyond the scope of this analysis. Researchers have pointed to benevolent (though misguided) intentions of policymakers. Others have argued that the numerous entrenched interests in continuing current U.S. drug policy, including police and prison guard unions, and the cadre of public and private individuals with some link to U.S. drug policy, are what continue to drive counterproductive drug policies. 125

Various reasons are offered for continuing the War on Drugs. Some argue that current policies are the best way to achieve the objectives of increased health and less crime. Others posit that the drug war is necessary to support America’s foreign policy objectives, including winning the War on Terror. Regardless, it is clear that current drug policy, whether examined from a domestic or international perspective, is an utter failure. The consequences are not merely monetary, although the $1 trillion of tax dollars spent since the 1970s is far from a trivial amount of money. As discussed above, U.S. drug policy has real implications for millions of otherwise innocent civilians. These unintended consequences range from jail time to missing out on educational opportunities to living in violent societies, and to death.

While states have started to move in a more lenient direction with regard to their drug policies, their efforts appear insufficient, as with domestic policy, there is a variety of low-hanging fruit. To give just one example, syringe services programs (SSPs) provide sterile syringes free of charge to drug users as a means to prevent the transmission of HIV/AIDS and hepatitis. These programs are effective not only at reducing disease transmission, but also at making neighborhoods safer for police, sanitation workers, and the general public by providing for the safe disposal of potentially infectious needles and syringes. These programs are also known to help drug users quit, as they provide users with information and access to treatment programs.

SSPs have the potential to save taxpayers millions of dollars, as heavy drug users are more likely to rely on public assistance programs. A clean syringe costs less than half a dollar, while treatment for HIV costs between $385,200 and $618,900. The Foundation for AIDS Research estimates that for every $1 spent on SSPs, an estimated $3 in health care costs is saved.126 Despite these benefits, however, it is currently illegal for federal funds to be used for these programs. Changing this mandate has the potential to better fulfill the goals of increased health and public safety than do current policies.

Conclusion

It is time to consider the broader decriminalization or legalization of drugs, from marijuana to harder substances, and to focus on a more treatment-based approached. While the idea of legalizing drugs such as heroin and cocaine may seem far-fetched, such a policy is not without precedent. In 2001, Portugal enacted one of the most extensive drug reforms in the world when it decriminalized possession of all illicit drugs but retained criminal sanctions for activities such as trafficking. Instead of making prohibition the main focus of its drug policy, the Portuguese government instead concentrated its efforts on treatment and harm reduction. The data from the Portuguese experience over the last 15 years illustrate how this marked policy shift ironically fulfills the purported goals of the War on Drugs.

First, Portugal has seen no major increase in rates of drug use, and the country’s rate of use remains below the European average and well below the average in the United States. Importantly, the use of drugs among particularly vulnerable populations, such as adolescents, has dropped.127 Under the new regime, even though usage rates have either remained flat or fallen, the number of people seeking treatment has increased by 60 percent. New HIV infections have fallen from 1,575 in 2000 to just 78 in 2013. The number of new AIDS cases over the same period fell from 626 to 74.128 Drug-induced deaths have also fallen from 80 deaths in 2001 to just 16 in 2012.129

The mechanisms behind these changes are no mystery to those familiar with the economics of prohibition. As one may expect, in a decriminalized regime, the information mechanisms allowing individuals to access information about quality are available. Users are now able to seek treatment or other assistance without self-incrimination.

A change in drug policy would likely have large positive effects with respect to racial issues in the United States. As mentioned above, minorities are much more likely to be incarcerated for drug offenses, as well as experience negative interactions with police. Drug liberalization would not only work to counter the ongoing trend of militarized police, but would work to limit the number of negative interactions between police and minority groups by eliminating the underlying reason for many raids, traffic stops, and other interactions.

When it comes to the international impacts of the War on Drugs, it is all the more apparent that policy changes are desperately needed. In the case of Afghanistan, for example, U.S. prohibition policies have failed to prevent the creation and sale of drugs—Afghanistan now produces more opium than ever before. The U.S. drug policies in Afghanistan have fostered widespread corruption and created a scenario in which Afghan citizens are unsure of what policies will be enacted and enforced, pushing them into the arms of the Taliban. The cartelization of the opium trade has provided a steady and substantial income for the Taliban. Thus, these drug policies not only fail in their own right, but actively undermine U.S. counterterrorism policy.

The consequences of the international War on Drugs do not only apply to Afghanistan. The U.S. government supports a variety of anti-drug policies throughout the world. Each of these programs consists of more of the same—drug prohibition and eradication. In each of these cases, we may reasonably expect, and observe, more of the same unintended consequences.

For more than 100 years, prohibition has been the primary policy in the United States with regard to illicit substances. As the data show, however, these policies fail on practically every margin. Economic thinking illustrates that these failures are not only understandable, but entirely predictable. As a result of prohibition and the changes it induces in the market for drugs, increased disease, death, violence, and cartels are all expectable outcomes. Moreover, economics can help us link together these policies with other issues, such as race relations and police militarization.

Liberal drug policies need to be seriously considered. While some states have taken active steps to lessen the sharp sting of U.S. drug policy, these are but a few drops of clean water in a sea of counterproductive mandates. Truly effective reform will not only require changes at the state level, but ultimately necessitate critical shifts in U.S. federal policies, both domestically and internationally.

Notes

- Quoted in Richard Branson, “War on Drugs a Trillion-Dollar Failure,” CNN, December 7, 2012, http://www.cnn.com/2012/12/06/opinion/branson-end-war-on-drugs/.

- Jeffrey Miron and Jeffrey Zwiebel, “Alcohol Consumption during Prohibition,” NBER Working Paper no. 3675, April 1991, http://www.nber.org/papers/w3675.pdf.

- Mark Thornton, “Alcohol Prohibition Was a Failure,” Cato Institute Policy Analysis no. 157, July 17, 1991, http://object.cato.org/sites/cato.org/files/pubs/pdf/pa157.pdf.

- Ibid.

- Federal Bureau of Prisons, U.S. Department of Justice, “Prisoners in 2015,” December 2016, https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/p15.pdf; Drug Policy Alliance, “Drug War Statistics,” 2016, http://www.drugpolicy.org/drug-war-statistics; and Drug War Facts, “Crime, Arrests, and US Law Enforcement,” 2016, http://www.drugwarfacts.org/cms/Crime#sthash.YB72ynK2.uGixeEd5.dpbs.

- Doug Lederman, “Drug Law Denies Aid to Thousands,” Inside Higher Ed, September 28, 2005, https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2005/09/28/drug.

- Michelle Alexander, The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness (New York: New Press, 2013).

- Drug Policy Alliance, “Drug War Statistics.”

- Ted Galen Carpenter, The Fire Next Door: Mexico’s Drug Violence and the Danger to America (Washington: Cato Institute, 2012).

- Jared Greenhouse, “How America’s War on Drugs Unintentionally Aids Mexican Drug Cartels,” Huffington Post, July 2, 2015, http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2015/07/02/us-mexico-drug-cartel_n_7707136.html.

- Christopher J. Coyne, Abigail R. Hall-Blanco, and Scott Burns, “The War on Drugs in Afghanistan: Another Failed Experiment in Interdiction,” Independent Review 21, no. 1 (2016): 95–119.

- Executive Office of the President, “National Drug Control Strategy,” 2015, https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/sites/default/files/ondcp/policy-and-research/2015_national_drug_control_strategy_0.pdf, p. iii.

- Ibid., 74.

- Jeffrey A. Miron and Jeffrey Zwiebel, “The Economic Case against Drug Prohibition.” Journal of Economic Perspectives (1995): 175–192.

- Brad Tuttle, “Legal Pot Prices Keep Getting Cheaper,” Time, April 22, 2015, http://time.com/money/3830017/legal-pot-cheap-prices/. See also the United States Office of National Drug Control, “Cocaine and Heroin Prices,” https://www.unodc.org/unodc/secured/wdr/Cocaine_Heroin_Prices.pdf.

- Jeffrey A. Miron, “The Effect of Drug Prohibition on Drug Prices: Evidence from the Markets for Cocaine and Heroin,” Review of Economics and Statistics 85 (1985): 522–30.

- Andrew J. Resignato, “Violent Crime: A Function of Drug Use or Drug Enforcement?” Applied Economics 32, no. 6 (2000): 681–88.

- Miron and Zwiebel, “The Economic Case against Drug Prohibition,” 178.

- Ibid.

- Gary S. Becker and Kevin M. Murphy, “Have We Lost the War on Drugs?” Wall Street Journal, January 4, 2013, http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424127887324374004578217682305605070.html.

- Arturo Zamora Jiménez, “Criminal Justice and the Law in Mexico,” Crime, Law, and Social Change, (2003): 33–36.

- David F. Musto, The American Disease: Origins of Narcotic Control (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999).

- L. Kolb, Drug Addiction: A Medical Problem (Springfield, IL: Charles C. Thomas, 1962).

- Richard Nixon, “Special Message to the Congress on Drug Abuse Prevention and Control,” June 17, 1971, http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=3048.

- “$1 Billion Voted for Drug Fight,” Syracuse Herald Journal, March 16, 1972.

- United States Drug Enforcement Agency, “Drug Enforcement Administration History: 1970–1975,” http://www.justice.gov/dea/about/history/1970–1975.pdf.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “Data Brief 81: Drug Poisoning Deaths in the United States, 1980–2008,” http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db81_tables.pdf#4.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “Increases in Drug and Opioid Overdose Deaths—United States, 2000–2014,” January 1, 2016, https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6450a3.htm.