Over its first two years, the Trump administration has aggressively reshaped U.S. trade policy. One of its most controversial initiatives is the expansive use of national security to justify imposing tariffs and quotas. Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962 gives the president authority to restrict imports on this basis after an investigation by the Department of Commerce. The administration has already done so for steel and aluminum and is now threatening similar actions on automobiles. The World Trade Organization (WTO) has a special exception for such measures, so there is at least an argument that they are permitted under international law.

However, the administration has taken what was previously considered a narrow and exceptional remedy and broadened it to serve as a more general tool to protect domestic industries. In the domestic arena, there have been court challenges against the tariffs imposed under Section 232 and against the constitutionality of Section 232 itself. In addition, legislation has been introduced in Congress to rein in the president’s authority by requiring congressional approval of tariffs or other import restrictions before they can go into effect. Internationally, many U.S. trading partners responded immediately to the steel and aluminum tariffs with tariffs of their own, and both the U.S. tariffs and the retaliatory tariffs are the subject of litigation that will test the limits of the WTO’s dispute settlement process and the trading system itself.

This study argues that WTO dispute settlement cannot easily resolve disputes of this kind and suggests an alternative mechanism to handle these issues. Instead of litigation, a rebalancing process like the one used in the context of safeguard tariffs and quotas should be utilized for national security measures. Safeguards are a political safety valve that allows the trading system to pursue broad-based liberalization by providing the flexibility to protect domestic industries under certain conditions (ideally, by offering compensatory liberalization elsewhere). By adopting a similar political arrangement for national security trade restrictions, the overall balance in the system can be preserved, permanent damage to the WTO dispute system avoided, and a potentially destructive loophole kept closed.

Introduction

The Trump administration has raised tariffs under a variety of pretenses, but one of the most controversial has been the invocation of national security under Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962. So far, only steel and aluminum imports have been assessed tariffs under this statute, but the administration soon may announce tariffs on automobiles and automobile parts, as well as on uranium and titanium sponges.

The administration has already received some strong pushback domestically to the steel and aluminum tariffs. There have been federal court challenges both to the tariff measures and to the constitutionality of the Section 232 statute itself. Meanwhile, Congress is considering various bills to rein in the president’s authority in this regard (Congress delegated some of its constitutional power over tariffs via the Section 232 statute and could take some of it back through new legislation). Congressional action would be the simplest and most straightforward way to restrain the Trump administration’s trade restrictions, but the political hurdle of convincing a Republican Senate to do this appears to be significant.

Beyond the domestic aspects of Section 232, there is also an international crisis over the Trump administration’s invocation of national security to justify tariffs. Many governments consider these actions to be in bad faith and a threat to the world trading system. Trade agreements involve a carefully balanced set of commitments to lower tariffs and other trade barriers. If countries can adopt protectionist measures simply by invoking national security, the trade liberalization achieved through such agreements may start to unravel.

To preserve the system, governments should consider new international trade rules to address trade barriers that have been justified as national security measures. The original drafters of the national security provisions of trade agreements recognized the sensitivity of this issue and hoped for the good-faith application of such measures. But good faith seems to be disappearing from the trade policy world, and additional rules may be needed. In this regard, rules that allow for national security trade barriers but that encourage trade liberalization for other products and services as compensation could prevent a spiral of protectionism and maintain the stability of the trading system.

History of the GATT/WTO Security Exception

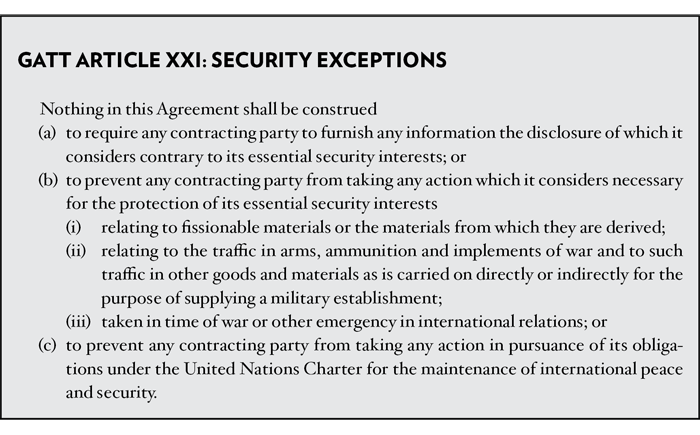

From the earliest proposals for an international trade organization, it was clear that the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) would include some sort of exception for security concerns. The specific wording evolved during negotiations, but in the final text of the GATT, Article XXI, titled “Security Exception,” explained that nothing in the agreement shall prevent a government from “taking any action which it considers necessary for the protection of its essential security interests.” When the WTO was created and trade rules were expanded to cover trade in services and intellectual property, the security exception was included for those areas as well.1

Over most of the history of the GATT/WTO, governments have, for the most part, been careful to invoke national security only when it was genuinely applicable. The original negotiators recognized the political difficulties that would arise and the potential for abuse, and governments presumably kept these concerns in mind over the ensuing decades.2 In one of the most comprehensive articles on this exception, written in 2011, legal scholar Roger Alford noted, “Member States have exercised good faith in complying with their trade obligations” as “invocations of the security exception have only been challenged a handful of times, and those challenges have never resulted in a binding GATT/WTO decision.” Alford recounted the few instances when tensions over Article XXI arose, including over export controls for Eastern Europe during the Cold War, an embargo of Argentina led by the European Community related to the Falklands War, and the U.S. embargoes on Nicaragua and Cuba.3 As a result of governments’ good-faith efforts, the GATT/WTO system has been able to avoid both major conflict over this issue and having to decide what Article XXI actually means.

The long period of harmony over Article XXI seems to be ending. A WTO dispute between Ukraine and Russia has provided the first WTO panel interpretation of the provision, but the more serious controversy will arise over the U.S. tariffs recently imposed by the Trump administration on imports of steel and aluminum.

The Trump Administration’s Aggressive Use of Section 232

Overview of Section 232

Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962 gives the president the authority to adjust imports on national security grounds.4 A decision to impose restrictions is based on an investigation by the Department of Commerce, which includes consultations with the Secretary of Defense. The Department of Commerce investigation can be self-initiated, or it can take place at the request of any U.S. department or agency or at the request of the domestic industry that stands to benefit from the restrictions.

During a Section 232 investigation, the Department of Commerce considers a number of factors, including domestic production needed for national defense requirements, the capacity of domestic industries to meet such requirements, and how the importation of goods affects such industries and affects the capacity of the United States to meet national security requirements. The department must also take into consideration the impact of foreign competition on the economic welfare of individual domestic industries. These factors make clear that the national security justification under the statute is tied closely to economic considerations.

The statute provides that the investigation shall last no longer than 270 days, and the Secretary of Commerce is required to submit a report to the president with recommendations of action or inaction.5 Within 90 days of receiving the report, the president will make a decision, and may either follow the recommendations of the Department of Commerce or take other actions.6 Generally speaking, these actions will be in the form of tariffs or quotas.

To date, there have been 31 Section 232 investigations. In 16 cases, the Department of Commerce determined that the goods did not threaten to impair national security. In 11 cases, the Department of Commerce found that the imported goods threatened to impair national security and provided recommendations to the president. (In 8 of these 11 cases, the president took action.) One case was terminated at the petitioner’s request before a conclusion was reached. Three investigations are still pending.7

The first 24 cases occurred from 1963 to 1994. After that, the mechanism fell into disuse. There was a case brought in 1999 and one in 2001, but then nothing for 16 years. Since President Trump took office in January 2017, there have been five Section 232 investigations, on steel, aluminum, autos and auto parts, uranium, and titanium sponges. The Trump administration’s tariffs on steel and aluminum were the first and second times that trade restrictions have been imposed under this law for a product other than oil or petroleum.8 In the two years since Trump’s election, his administration has clearly tried to expand the scope of this previously narrow remedy.

Both Congress and private actors have tried to push back against the administration’s aggressive use of Section 232. Multiple bills are under consideration in Congress, and court challenges have been initiated against specific tariffs and against the Section 232 statute itself.9 These efforts could lead to a more appropriate allocation of powers between Congress and the president on trade and national security issues. However, as will be seen later, they would not necessarily address the international aspects of trade restrictions that are based on national security, which can arise even without an executive branch that is willing to push the boundaries of the law in order to pursue protectionist policies.

The Section 232 Actions on Steel and Aluminum

Trump’s enthusiasm for heavy manufacturing in general, and for steel and aluminum in particular, was evident during his election campaign. “We are going to put American steel and aluminum back into the backbone of our country,” Trump vowed at a 2016 campaign rally in a former steel town in Pennsylvania.10 Steel and aluminum were at the center of his America First trade policy.

After Trump took office, it quickly became clear that the administration might impose broad tariffs on steel and aluminum imports, using Section 232 as the vehicle. In April 2017, Trump instructed the Department of Commerce to initiate investigations on the national security threat posed by steel and aluminum imports.11 The department immediately initiated Section 232 investigations on steel and aluminum and sought public comments.12

In January 2018, the department issued its reports. It concluded that the importation of certain types of steel and aluminum products threatened to impair the national security of the United States and recommended that the president reduce imports through tariffs or quotas, suggesting three options each for steel and aluminum. For steel it recommended a tariff of 24 percent on all steel imports; a tariff of 53 percent or more on steel imports from 12 countries, plus a quota for all other nations that equaled their exports to the United States in 2017; or a quota of 63 percent of each country’s 2017 steel exports to the United States. For aluminum it recommended a tariff of 7.7 percent on all aluminum imports; a tariff of 23.6 percent on aluminum imports from five countries, plus a quota for all other nations that equaled their exports to the United States in 2017; or a quota of 86.7 percent of each country’s 2017 aluminum exports to the United States.13

On March 8, 2018, Trump issued two proclamations that imposed a 25 percent tariff on steel products and a 10 percent tariff on aluminum products; they were set to take effect on March 23, 2018. Some countries negotiated export quotas to avoid the tariffs, and others received temporary tariff exemptions, but as of June 1, 2018, the tariffs were being imposed on most U.S. trading partners.14 The tariffs have been estimated to apply to $44.9 billion worth of steel and aluminum imports.15

In terms of the actual purpose of the actions, there were reasons to doubt the claimed national security justification, as the Defense Department was skeptical of the value of the tariffs. Then secretary of defense James Mattis expressed concern that tariffs would sabotage relationships with key allies.16 He also acknowledged that the military’s requirements for steel and aluminum could be satisfied with about 3 percent of domestic production, casting doubt on the concerns about the impact of imports and on the justification of the Section 232 actions.17

Beyond national security, a number of explanations have been offered by Trump to justify the tariffs. At times, he has emphasized that the tariffs would protect the U.S. economy and jobs.18 He has also linked the tariffs to trade negotiations, suggesting that the tariffs have forced U.S. trading partners to the negotiating table.19 A further explanation is that the tariffs are being used to combat unfair trade practices.20 Ultimately, we do not know the true motivation of Trump for these tariffs, and views may vary within the administration. But it is worth noting that Trump often makes it clear that he simply likes tariffs.21

Many U.S. trading partners responded quickly to the imposition of the Section 232 tariffs by imposing retaliatory tariffs. Their argument was that the Section 232 measures are not really about national security but are in fact more like a safeguard measure designed to protect domestic industries from injury caused by imports. As a result, the special rebalancing provisions of the Safeguards Agreement (discussed in more detail below) apply here and justify immediate retaliation.22

In addition to the retaliatory tariffs, from April to August 2018 nine governments requested consultations at the WTO, which is the first step in WTO litigation. From November 2018 to January 2019, dispute settlement panels were established to hear the cases. In late January, the panels were appointed, and litigation will soon begin.23

The complainants’ legal claims are fairly straightforward, focusing on GATT Article I (MFN treatment) and GATT Article II (tariff commitments). As discussed in the next section, the U.S. defense constitutes a serious threat to the system, as the United States has invoked GATT Article XXI. As repeatedly stated by the United States at the relevant meetings of the WTO’s Dispute Settlement Body (DSB), in the U.S. view, after Article XXI is invoked the panel cannot even hear the case.24

While the steel and aluminum tariffs have caused great friction, an even bigger test of Section 232 lies ahead: the Department of Commerce has completed a Section 232 investigation on imports of automobiles and auto parts, and Trump is considering whether to take action against imports of these products based on the allegation that they are a national security threat.25 The value of trade potentially affected would be much larger than that of steel and aluminum. It is estimated that the Section 232 auto tariffs could cover more than $200 billion of auto and auto parts imports.26Some U.S. trading partners have already warned that they will retaliate if tariffs are imposed.27

The Threat to the WTO Dispute Settlement Mechanism

The administration’s use of Section 232 presents a challenge to the WTO dispute settlement system, and even to the WTO itself, because of the invocation of GATT Article XXI. WTO dispute settlement has had success over the years in adjudicating core trade issues such as ordinary tariffs, trade remedy tariffs, and regulatory trade barriers. It cannot induce governments to remove the measures that violate WTO rules in every case, but it has a fairly good record here. However, there are limits to what can be achieved, and it is clear that some sensitive measures cannot be dealt with through WTO litigation. National security measures pretty clearly fall into this category, and thus litigation of these measures has been carefully avoided over the years. But after decades of restraint over litigating the scope and meaning of Article XXI, the Section 232 measures threaten to undermine the system by creating a WTO litigation outcome that either takes the U.S. view and opens a Pandora’s box involving a proliferation of invocations of national security as a basis for trade restrictions, or rejects the U.S. view and risks the Trump administration pulling out of the WTO.

The problem with applying and interpreting Article XXI in these cases is part legal and part political. In terms of the law, there is no simple answer on the provision’s meaning. The use of the word “considers” in subparagraphs (a) and (b) of Article XXI gives the provision a self-judging nature, but the question is how far to take this. Alford describes the interpretive possibilities as follows:

According to one interpretation, a Member State can decide for itself whether a measure is essential to its security interests and relates to one of the enumerated conditions. Another interpretation would recognize a Member State’s prerogative to determine for itself whether a security exception is applicable, but would impose a good faith standard that is subject to judicial review. Under a third interpretation, a Member State can decide for itself whether “it considers” a measure to be “necessary for the protection of its essential security interests,” but the enumerated conditions are subject to judicial review.28

Questions about the scope of the exception were raised during the GATT negotiations, but they are not easy to resolve as an interpretive matter.29

This legal uncertainty is reflected in a political divide. Two leading powers, the United States and Russia, take one view of the provision’s interpretation, while most of the WTO membership takes another (as made clear by the parties’ submissions in a recently decided WTO case called Russia—Traffic in Transit). On one side, the United States and Russia argued that the WTO security provisions are nonjusticiable, meaning it is left entirely to governments to decide whether to impose trade restrictions for this purpose. In their view, once a party has invoked Article XXI, the WTO panel can no longer hear the case.30 In contrast, other members believe that WTO panels must engage in some degree of scrutiny of measures for which Article XXI has been invoked.31

The WTO panel in the Russia—Traffic in Transit case recently provided the first word on the issue of interpretation of GATT Article XXI, taking the view that the provision is not entirely self-judging and leaving room for some panel scrutiny.32 Other ongoing WTO panels that are hearing cases on similar issues may approach the interpretation of this provision similarly, but it is possible that there will be some variation in approaches. The Russia—Traffic in Transit panel report was not appealed, which means that the Appellate Body has not considered the issue. At some point in the future, the Appellate Body may provide additional clarification. The state of the Appellate Body reappointment process adds some complexity here. Currently, the United States is blocking the appointment of new Appellate Body judges, which has created a backlog of appeals and the possibility that by the end of the year there will not be enough people on the Appellate Body to hear cases.33

However, a problem larger than figuring out the proper interpretation of the provision looms: if a WTO panel or the Appellate Body were to rule that Article XXI did not justify the U.S. steel and aluminum tariffs, would the United States comply with the ruling? Given the U.S. rhetoric on the issue, it seems unlikely.34 (Worse yet, the Trump administration may pull out of the WTO. It has long complained that the organization’s dispute-settlement rulings are unfair to the United States.)35 In the event of noncompliance, the only remedy is for the DSB to authorize a suspension of concessions under which the complainants could impose tariffs or other retaliation of their own, but most of the complainants have already retaliated, relying on the legal theory that the U.S. measures are safeguard measures and that rebalancing under Safeguards Agreement Article 8 is permitted immediately.36 As a matter of law, such an assertion has little basis and further undermines confidence in the system.37 Responding to violations of the rules with other violations of the rules leaves everyone wondering if the rules have any value.

As a result, it is unclear how WTO dispute settlement can help in this case. Trump’s Section 232 actions called attention to the possibility of a broad national security loophole and triggered a response that could be characterized as abuse of the safeguards-rebalancing rules. In this environment there is a real worry that the system will no longer function.

While rebalancing as practiced by U.S. trading partners here may fail to solve the problem, the concept may nevertheless offer a way forward for this kind of dispute. Adapting it for use directly in the context of national security could provide a solution to the impasse. An attempt to expand the existing safeguard rules for rebalancing beyond their scope undermines the rule of law, but a new rebalancing regime designed specifically for the national security context could help restore it.

Rebalancing under the Safeguards Agreement

The idea of some type of rebalancing in response to safeguard measures originates in the reciprocal trade agreements negotiated by the United States and other countries in the 1930s. The first modern safeguard provision appeared in the United States-Mexico Reciprocal Trade Agreement of 1942. It provides that when a country will “withdraw or modify a concession” as a safeguard to protect domestic industry, “it shall give notice in writing to the Government of the other country as far in advance as may be practicable and shall afford such other Government an opportunity to consult with it in respect of the proposed action”; if no agreement is reached, the other government “shall be free within thirty days after such action is taken to terminate this Agreement in whole or in part on thirty days’ written notice.”38 The consultations provide an opportunity for the parties to reach agreement on compensation, for example, lowering tariffs on other products.39

This idea was carried over to the GATT negotiations, where the United States proposed the initial text. At this point, “terminat[ion]” was replaced with “suspension of obligations or concessions” as the appropriate response when compensation could not be agreed on.40 The provision was refined further during the negotiations, and the London Draft of the GATT refers to suspension of “substantially equivalent obligations or concessions.”41 In the final version of the GATT, the relevant provisions appear in Article XIX, paragraphs 2 and 3.42

Practice under the GATT suggests that compensation was used extensively early on but tapered off over the years. As of 1987, there had been 20 instances of agreement or offers of compensation (10 cases during 1950–1959, 8 in 1960–1969, 1 in 1970–1979, and 1 in 1980–1987).43

During the Uruguay Round of trade negotiations, the specific requirements for rebalancing were elaborated further in the Safeguards Agreement. Under Article 8 of the agreement, a government proposing to apply a safeguard measure or seeking an extension of one shall try to maintain a substantially equivalent level of concessions and other obligations, and in order to achieve this objective, “the Members concerned may agree on any adequate means of trade compensation for the adverse effects of the measure on their trade.”44 If compensation cannot be agreed on, retaliation is permitted almost immediately in cases where the justification for the safeguard measure is based only on a relative increase in imports, but it has to wait three years if there has been an absolute increase in imports.45

Why Rebalance at All?

The basic idea behind rebalancing is as follows. When countries negotiate trade agreements, the concessions and other obligations they take on—including commitments to reduce tariffs, commitments to avoid certain protectionist domestic laws, and various other requirements—are part of an overall balance. Roughly speaking, each side accepts a particular degree of liberalization or other obligations, which constitutes the balance that was agreed to.

There are times when things get out of balance, however. One example is when a government that is a party to the agreement believes that another party has taken actions that violate the agreement. After adjudication of the dispute, if a violation is found, the offending government can remove or modify the measure or offer some sort of compensation. If it does neither, it will be subject to trade retaliation by the complaining government in an amount equivalent to the effect of the violation. In this way, balance is restored.

In some circumstances, adjudication is not first required. In the context of safeguards, the very nature of the measure indicates that the balance has been upset. If a government imposes a tariff or quota as a safeguard measure, with rare exceptions that measure will constitute withdrawal or modification of a tariff concession or breach of the obligation not to impose quotas. When that happens, the balance needs to be restored. Ideally, rebalancing would take place through compensation in the form of trade liberalization in other areas by the government imposing the safeguard measure. However, when compensation cannot be worked out, the affected countries are allowed to raise their own tariffs in an equivalent amount. Such a scenario may not be ideal, but it acts as a deterrent against the abuse of safeguard measures.

A Rebalancing Proposal for National Security

Under WTO rules, governments may impose tariffs and other trade restrictions beyond what was agreed for a variety of reasons, including for temporary protection as safeguards; as a response to dumping or subsidies; for environmental, public morals, or public health reasons; or in support of national security. Whether to make rebalancing available is a political and policy decision. Traditionally, immediate rebalancing has been available only for safeguards, but the case could be made for rebalancing in other contexts too.

In the national security context, there are several arguments for allowing a similar kind of rebalancing. First, retaliation is already happening. In the case of the Section 232 tariffs, as noted above, a number of governments have declared the measures to be safeguard measures and have applied retaliatory tariffs. Instituting rebalancing rules in these cases would provide an opportunity to replace retaliatory tariffs with compensatory liberalization, which is impossible with the current retaliatory tariffs as the United States does not accept that the safeguards rules even apply here. In addition, in circumstances when compensation is impossible, rebalancing would formalize the retaliation process and make it more orderly, limiting the possibility of a trade war that spirals out of control.

Second, as explained earlier, WTO dispute settlement probably cannot help here. A ruling that the Section 232 measures violate GATT obligations and are not justified under Article XXI is unlikely to make the United States comply, and retaliation is already being imposed by many countries even without authorization.

Third, national security measures are like safeguard measures in the sense that there is often no debate about their consistency with the rules. It is acknowledged that they violate the rules, and national security is offered as the excuse. This makes national security more like safeguard measures than, say, environmental regulations, where the responding party generally argues that the regulation is not in violation.

Finally, rebalancing would afford an important benefit by limiting the abuse of the provisions. A full WTO dispute proceeding typically lasts from two to four years, depending on the complexity of the case. National security measures are particularly susceptible to abuse due to the vagueness of the national security exception’s language, and rebalancing would reduce the time that governments can impose import restrictions for national security purposes without any response from trading partners.

Rebalancing of national security measures can draw on principles from the safeguards arena but would have its own characteristics and a different focus.

One of the primary goals of national security rebalancing would be transparency. As things stand now, governments have the ability to impose trade restrictions for protectionist purposes but can later invoke Article XXI during litigation. It would be preferable to have all national security trade restrictions notified as such immediately to foster proper debate and discussion. Bringing these cases to light early, and having WTO members think carefully about the proper scope of the exception, would be of great value. To this end, the national security rebalancing rules should encourage notification and explanation of national security tariffs by offering more time before rebalancing can be applied when restrictions have been notified. For example, rebalancing can be immediate when an Article XXI justification is invoked as part of litigation when no notification or explanation has been given, but must wait six months to a year when notification has been given.

To help oversee the discussions, a WTO Committee on National Security Measures should be formed to examine these measures and any proposed rebalancing. Members should meet regularly to consider the practice in this area.

Compensation is the preferred approach to rebalancing. Ideally, governments that impose tariffs or other restrictions on specific products for national security purposes would offer to reduce tariffs or restrictions on other products or services. Adding services as a compensation option may be significant. One of the reasons compensation has worked less well in recent years in the safeguards context is that as tariff levels have decreased, it has become harder for countries invoking safeguards to find alternative products on which they could give meaningful concessions.46 Adding services to the mix would open a wide range of compensation possibilities, especially considering how few services commitments most countries have made and thus how much potential exists for additional liberalization.

Negotiations over the extent of the compensation will never be easy, but they can be facilitated through carefully designed rules. For example, there could be a requirement that in order to impose an import restriction for national security reasons, a government must identify three products or services for which it would consider negotiating compensatory liberalization.

When compensation cannot be agreed upon, however, retaliation designed to restore balance is a possibility. To prevent abuse, a quick arbitration process should be established for determining whether any retaliation is commensurate with the economic impact of the national security restrictions in question.

Conclusion

Not every dispute can be resolved through litigation. U.S. constitutional law has the political question doctrine. A similar principle may be appropriate for certain international trade disputes.

The proposals outlined here are designed to help provide a political solution to disputes over trade restrictions based on national security. They are fairly straightforward as a policy matter, although much more debate is needed.

The politics are more complicated, of course. The Trump administration is the main party pushing the boundaries of national security restrictions, so for the time being the United States is unlikely to be open to any reforms. The views of a future U.S. administration are uncertain but may not differ considerably from the current position.

As a result, any hope for change may have to come from other governments as they negotiate bilaterally, regionally, or on a plurilateral basis with countries that are interested in pursuing this idea. Governments that are concerned about the abuse of national security measures can incorporate provisions along these lines in agreements they sign that do not involve the United States. In this way, the norm can spread, with the hope that its usefulness will be demonstrated and with the aim of eventual inclusion in a multilateral agreement.

Notes

1. See Article XIV bis, General Agreement on Trade in Service, and Article 73, Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights.

2. Simon Lester, “The Drafting History of GATT Article XXI: The U.S. View of the Scope of the Security Exception,” International Economic Law and Policy Blog, March 11, 2018; Simon Lester, “The Drafting History of GATT Article XXI: Where Did ‘Considers’ Come From?,” International Economic Law and Policy Blog, March 13, 2018.

3. Roger P. Alford, “The Self-Judging WTO Security Exception,” Utah Law Review 3 (2011): 697, 706–25. See also Tania Voon, “The Security Exception in WTO Law: Entering a New Era,” American Journal of International Law 113 (2019): 45–50.

4. 19 U.S.C. §1862.

5. 19 U.S.C. §1862(b)(3).

6. 19 U.S.C. §1862(c).

7. Congressional Research Service, “Section 232 Investigations: Overview and Issues for Congress,” April 2, 2019.

8. In addition, in a case on machine tools that was initiated in 1983, a formal decision on the Section 232 case was deferred, and the president “instead sought voluntary restraint agreements starting in 1986 with leading foreign suppliers and developed a domestic plan of programs to help revitalize the industry.” Congressional Research Service, “Section 232 Investigations: Overview and Issues for Congress,” Table B‑1, April 2, 2019.

9. Legislative proposals aimed at restricting presidential power under Section 232 include the Bicameral Congressional Trade Authority Act of 2019, sponsored by Senator Pat Toomey and others (Bicameral Congressional Trade Authority Act of 2019, S.287/H.R.940, 116th Cong. [2019]); and the Trade Security Act of 2019, sponsored by Senator Rob Portman and others (Trade Security Act of 2019, S.365/H.R.1008, 116th Cong. [2019]). With regard to the courts, the Swiss company Severstal filed a case challenging the Section 232 steel tariffs, but after the Court of International Trade rejected a motion for a temporary restraining order, the parties filed a joint motion to dismiss. Inside U.S. Trade, “CIT Judge Unconvinced Severstal Can Succeed on Merits in 232 Challenge,” InsideTrade.com, April 5, 2018. In addition, the American Institute for International Steel brought a case claiming that the Section 232 statute is unconstitutional, which is currently pending before the Court of International Trade. Inside U.S. Trade, “In Steel Case, CIT Judges Probe Broad Executive Powers under Section 232,” InsideTrade.com, December 21, 2018.

10. Susan Jones, “Trump: ‘Put American Steel and Aluminum Back into the Backbone of Our Country,’” CNSNews, June 29, 2016.

11. Administration of Donald J. Trump, “Memorandum on Steel Imports and Threats to National Security,” April 20, 2017; Administration of Donald J. Trump, “Memorandum on Aluminum Imports and Threats to National Security,” April 27, 2017.

12. Department of Commerce, “Notice of Request for Public Comments and Public Hearing on Section 232 National Security Investigation of Imports of Steel,” 82 Fed. Reg. 19205, April 26, 2017; Department of Commerce, “Notice of Request for Public Comments and Public Hearing on Section 232 National Security Investigation of Imports of Aluminum,” 82 Fed. Reg. 21509, May 9, 2017.

13. Office of Public Affairs, U.S. Department of Commerce, “Secretary Ross Releases Steel and Aluminum 232 Reports in Coordination with White House,” press release, February 16, 2018.

14. Congressional Research Service, “Section 232 Investigations: Overview and Issues for Congress,” Table D‑1, April 2, 2019.

15. Sherman Robinson et al., “Trump’s Proposed Auto Tariffs Would Throw U.S. Automakers and Workers under the Bus,” Peterson Institute for International Economics, May 31, 2018.

16. Ellen Mitchell, “Trump Tariffs Create Uncertainty for Pentagon,” The Hill, March 11, 2018.

17. Mitchell, “Trump Tariffs Create Uncertainty for Pentagon.”

18. Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump), “We must protect our country and our workers. Our steel industry is in bad shape. IF YOU DON’T HAVE STEEL, YOU DON’T HAVE A COUNTRY!,” Twitter post, March 2, 2018, 5:01 a.m.

19. Andrew Mayeda, “Trump Turns Steel Tariffs into NAFTA Bargaining Chip,” Bloomberg.com, March 6, 2018.

20. A White House fact sheet explained, “President Donald J. Trump is addressing global overcapacity and unfair trade practices in the steel and aluminum industries by putting in place a 25 percent tariff on steel imports and 10 percent tariff on aluminum imports.” White House, “President Donald J. Trump Is Addressing Unfair Trade Practices That Threaten to Harm Our National Security,” Fact Sheet, March 8, 2018.

21. Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump), “I am a Tariff Man. When people or countries come in to raid the great wealth of our Nation, I want them to pay for the privilege of doing so. It will always be the best way to max out our economic power. We are right now taking in $billions in Tariffs. MAKE AMERICA RICH AGAIN,” Twitter post, December 4, 2018.

22. Canada imposed 10–25 percent tariffs on approximately $12.05 billion of U.S. exports. Mexico imposed tariffs ranging from 7 to 25 percent on $3.52 billion of U.S. exports. The European Union imposed 10–25 percent duties on $2.91 billion worth of U.S. products. China imposed 15–25 percent tariffs on $2.52 billion worth of U.S. products. Russia and Turkey also imposed tariffs on selected U.S. products, ranging from 4 to 140 percent. See Congressional Research Service, “Section 232 Investigations: Overview and Issues for Congress,” April 2, 2019, figure 5; International Trade Administration, “Current Foreign Retaliatory Actions.”

23. Simon Lester, “Panels Composed in the Section 232/Retaliation Cases,” International Economic Law and Policy Blog, January 28, 2019.

24. World Trade Organization, “Panels Established to Review U.S. Steel and Aluminum Tariffs, Countermeasures on U.S. Imports,” November 21, 2018.

25. David Lawder and David Shepardson, “U.S. Agency Submits Auto Tariff Probe Report to White House,” Reuters, February 17, 2019.

26. Robinson et al., “Trump’s Proposed Auto Tariffs Would Throw U.S. Automakers and Workers under the Bus.”

27. Doug Palmer and Megan Cassella, “U.S. Allies Warn of Retaliation If Trump Imposes Auto Tariffs,” Politico, July 19, 2018.

28. Alford, “The Self-Judging WTO Security Exception.”

29. Lester, “The Drafting History of GATT Article XXI: The U.S. View of the Scope of the Security Exception”; Lester, “The Drafting History of GATT Article XXI: Where Did ‘Considers’ Come From?”; Lester, “More GATT Article XXI Negotiating History,” International Economic Law and Policy Blog, May 1, 2018.

30. Russia states that “neither the Panel nor the WTO as an institution has a jurisdiction” over the dispute. Russia’s first written submission, para. 7, cited in “European Union Third-Party Written Submission, Russia—Measures Concerning Traffic in Transit (DS512),” para. 10, November 8, 2017. Along the same lines, the United States argues, “The text of Article XXI, establishing that its invocation is non-justiciable, is supported by the drafting history of Article XXI. In particular, certain proposals from the United States during that process demonstrate that the revisions to what became Article XXI reflect the intention of the negotiators that the defence be self-judging, and not subject to the same review as the general exceptions contained in GATT 1994 Article XX.” “Responses of the United States of America to Questions from the Panel and Russia to Third Parties, Russia—Measures Concerning Traffic in Transit (DS512),” para. 3, February 20, 2018.

31. For instance, the EU argues that “Article XXI of GATT 1994 is a justiciable provision and that its invocation by a defending party does not have the effect of excluding the jurisdiction of a panel.” “European Union Third-Party Written Submission, Russia—Measures Concerning Traffic in Transit (DS512),” para. 21, November 8, 2017; and Australia argues, “[T]his deference to Russia does not preclude the Panel from undertaking any review of Russia’s invocation of Article XXI(b) or dispense with the Panel’s obligation to undertake an objective assessment of the matter before it, including an objective assessment of the facts of the case.” “Australia’s Third-Party Executive Summary, Russia—Measures Concerning Traffic in Transit (DS512),” para. 30, February 27, 2018.

32. WTO Panel Report, “Russia—Measures Concerning Traffic in Transit,” WT/DS512/R, adopted April 26, 2019.

33. James Bacchus, “How to Solve the WTO Judicial Crisis,” Cato at Liberty (blog), August 6, 2018.

34. In a recent DSB meeting, the United States reiterated that its invocation of Article XXI should not be reviewed by the panel: “[A WTO review] would undermine the legitimacy of the WTO’s dispute settlement system and even the viability of the WTO as a whole.” Inside U.S. Trade, “Azevêdo: Challenging U.S. 232 Tariffs at WTO a ‘Risky’ Strategy,” InsideTrade.com, December 6, 2018.

35. Gina Chon, “Trump’s Anti-WTO Rhetoric Hurts America First,” Reuters.com, December 11, 2017.

36. For an overview of rebalancing under the Safeguards Agreement, see Matthew R. Nicely and David T. Hardin, “Article 8 of the WTO Safeguards Agreement: Reforming the Right to Rebalance,” St. John’s Journal of Legal Commentary 23 (2008): 699.

37. Simon Lester, “How to Determine If a Measure Constitutes a Safeguard Measure,” International Economic Law and Policy Blog, August 15, 2018.

38. United States of America and Mexico, Reciprocal Trade Agreement, article XI, para. 2, December 23, 1942, 57 Stat. 833 (1943), E.A.S. No. 311.

39. John Jackson, World Trade and the Law of GATT (Charlottesville, VA: Michie Company, 1969), p. 565.

40. Suggested Charter for an International Trade Organization of the United Nations, article 29, para. 2, Publication 2598, Washington: Department of State.

41. London Draft of a Charter for an International Trade Organization, article 34, para. 2, Report of the First Session of the Preparatory Committee, UN Conference on Trade and Employment, UN Doc. E/PC/T/33 (Oct. 1946).

42. GATT, article XIX, paras. 2 and 3, April 15, 1994, 1867 U.N.T.S. 187.

43. “Drafting History of Article XIX and Its Place in GATT,” Background Note by the Secretariat, MTN.GNG/NG9/W/7, para. 22, September 16, 1987; and GATT Analytical Index, p. 525.

44. Article 8, para. 1, Agreement on Safeguards, April 15, 1994, WTO Agreement, Annex 1A.

45. Article 8, para. 3, Agreement on Safeguards states, “The right of suspension referred to in paragraph 2 shall not be exercised for the first three years that a safeguard measure is in effect, provided that the safeguard measure has been taken as a result of an absolute increase in imports and that such a measure conforms to the provisions of this Agreement.”

46. John Jackson, The World Trading System (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1994), p. 168; Chad Bown and Meredith Crowley, “Safeguards in the World Trade Organization,” February 2003. (“Although compensation for safeguard measures was often negotiated in the 1960s and 1970s, as tariff rates fell and more products came to be freely traded, as a practical matter, it became difficult for countries to agree on compensation packages”); see also Matthew R. Nicely and David T. Hardin, “Article 8 of the WTO Safeguards Agreement: Reforming the Right to Rebalance,” St. John’s Journal of Legal Commentary 23 (2008): 699, 716.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.