Brandt v. United States

Learn more about Cato’s Amicus Briefs Program.

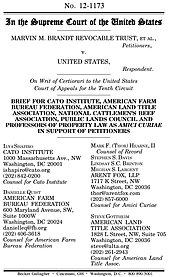

In the 19th Century, when railroads were being built across the West, the federal government granted significant land and benefits to railroad companies. The Great Railroad Right‐of‐Way Act of 1875 empowered the government to grant railroad companies right‐of‐way easements to build tracks across others’ land to facilitate the expansion of the nation’s railways — that is, railroads were granted a right to use sections of another’s property for railroad purposes without owning title to the land underneath. In 1976, the government sold the Brandt family a parcel of land in Wyoming which was crossed by one of these railroad easements. In 2001, the railroad that owned the easement formally abandoned all claims to it. Typically, when this happens, the easement is simply extinguished and the owner of the land may then use the former easement however he or she wishes. But the federal government had different plans for the thin strip running through the Brandts’ land. In 2006, the government sued for title to the land lying under the former easement on the theory that it had retained a “reversionary interest” in the land when granting the railroad the right of way easement, even though it never actually set aside any interests when granting the easement. The government thus claimed that after the railroad abandoned the easement (after only ever owning an easement and never full title to the land), full title to the land “reverted” back to the federal government. The Brandts argue that under the basic principles of the common law of property, the government had no such right, and that even if any legislative act allowed the government to somehow acquire their land, such an act would require payment of just compensation under the Fifth Amendment’s Takings Clause. After the trial court rejected its radical claims, the government appealed to the Tenth Circuit. In a puzzling decision, the Tenth Circuit split with the Seventh and Federal Circuit courts (and ignored some of its own precedent on the way) and held that the government did indeed have a reversionary interest in the land, even though it never actually carved itself an exception, as the law requires. The Brandts, faced with the uncompensated government confiscation of a strip of land cutting their property in two, have now brought their case to the Supreme Court in an attempt to keep the government’s hands off their land and off the land of thousands of other landowners in their same position. Cato, four other groups, and several property law professors — including Richard Epstein — have filed a brief supporting the Brandts’ fight against the government’s poorly justified land‐grab. We argue that the Tenth Circuit’s decision threatens to unsettle longstanding presumptions of property law because it willfully ignores basic differences between easements and “fee estates” in land and other basic principles of property law like the “strip and gore” doctrine (which holds, for example, that land under a right‐of‐way is split down the center and owned by those who own the land on either side of the easement). This case is important, because there are many thousands of miles of old railroad rights‐of‐way crossing the countryside that would be potentially subject to uncompensated government confiscation if the Court were to follow the Tenth Circuit’s approach. In addition, some 3,000 to 4,000 miles of old railroad easements are abandoned every year. It’s not entirely surprising that the government would go full throttle on such a shoddy legal argument for the chance to be able to snatch this land back without having to pay for it. The surprising thing is that the Tenth Circuit green‐lighted it. We urge the Supreme Court to switch tracks.