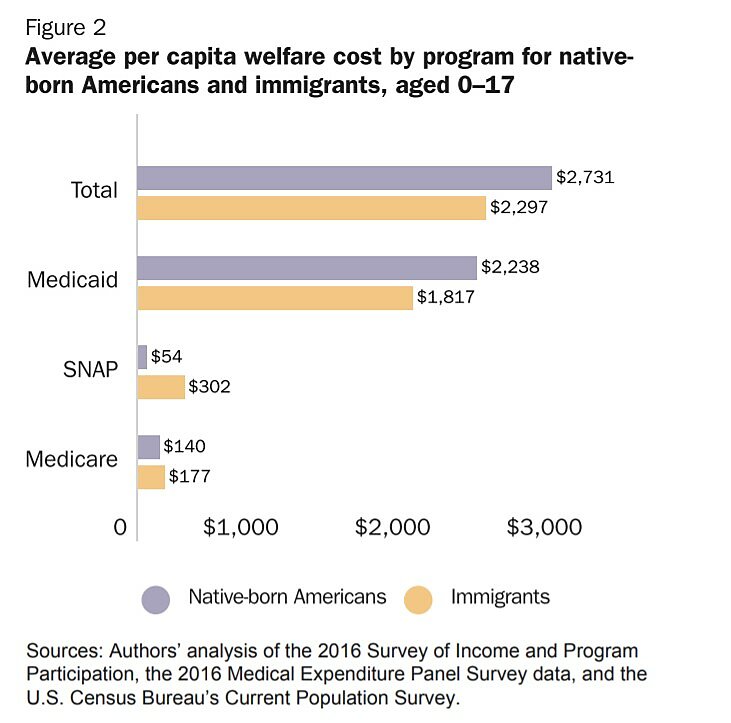

Immigrant consumption of welfare benefits has been a contentious policy issue for decades. This brief updates previous Cato policy briefs on immigrant welfare consumption in an attempt to supply better evidence to policymakers.1 The federal government spent more than $2.3 trillion in 2016 on the welfare state, an amount equal to approximately 60 percent of all federal outlays in that year.2 About $1.6 trillion of those expenditures went to Social Security and Medicare, whose intended beneficiaries are the elderly, while the other $700 billion went to means‐tested welfare benefits, whose intended beneficiaries are the poor.3

Eligibility for means‐tested programs and the value of their benefits are based on a variety of factors including recipients’ immigration status, income, and employment. For the purposes of this brief, means‐tested programs include Medicaid, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), Supplemental Security Income (SSI), Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), and Women, Infants, and Children (WIC).

Entitlement programs are intended to aid the elderly, and age is the primary eligibility requirement for entitlements. The amount of tax recipients paid into the program and the number of years they worked also affect their eligibility and the value of benefits they receive. For the purposes of this brief, Medicare and Social Security benefits (SSB) are entitlement programs. Social Security benefits include self‐benefits and benefits on behalf of children. The Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP) doesn’t survey every welfare or entitlement program, but the programs that it does survey cover 93 percent of American welfare state spending in 2016.