1 8 U.S.C. § 1101(a)(15)(H)(ii)(a) (2018); 20 C.F.R. § 655.103(d) (2019).

2 The program had a de facto practice of approving year-round sheep and goat herders. USCIS will terminate its practice in June 2020, and the Department of Labor will rescind its policy in 20 C.F.R. § 655.215(b)(2) (2019) by regulation. See Citizenship and Immigration Services, “Policy Memorandum—Subject: Temporary or Seasonal Need for H-2A Petitions Seeking Workers for Range Sheep and/or Goat Herding or Production,” PM-602-0176, November 14, 2019.

3 Glenn E. Garrett, Mexican Farm Labor Program Consultants Report: October 1959 (Washington: DOL, 1959), p. 5.

4 8 U.S.C. § 1101(a)(15)(H)(ii)(a) (2018).

5 “For example, because of confusion regarding the H-2A regulations, one employer expressed uncertainty about the appropriate time to reimburse workers for their in-bound travel costs, payment of which must be included in the job offer. The H-2A regulations specify that workers must be reimbursed upon the completion of 50 percent of their work contract but also that H-2A employers may be subject to the Fair Labor Standards Act, under which employers are to make such reimbursements during the first week of employment.” Cited in: Government Accountability Office, H-2A Visa Program: Modernization and Improved Guidance Could Reduce Employer Application Burden, GAO-12-706 (Washington: GAO, September 2012), p. 25.

6 Office of the Citizenship and Immigration Services Ombudsman, Annual Report 2014 (Washington: DHS, June 27, 2014).

7 8 U.S.C. § 1188 (2018); 20 C.F.R. § 655.100. (2019).

8 “About NASWA,” National Association of State Workforce Agencies.

9 20 C.F.R. § 655.121 (2019).

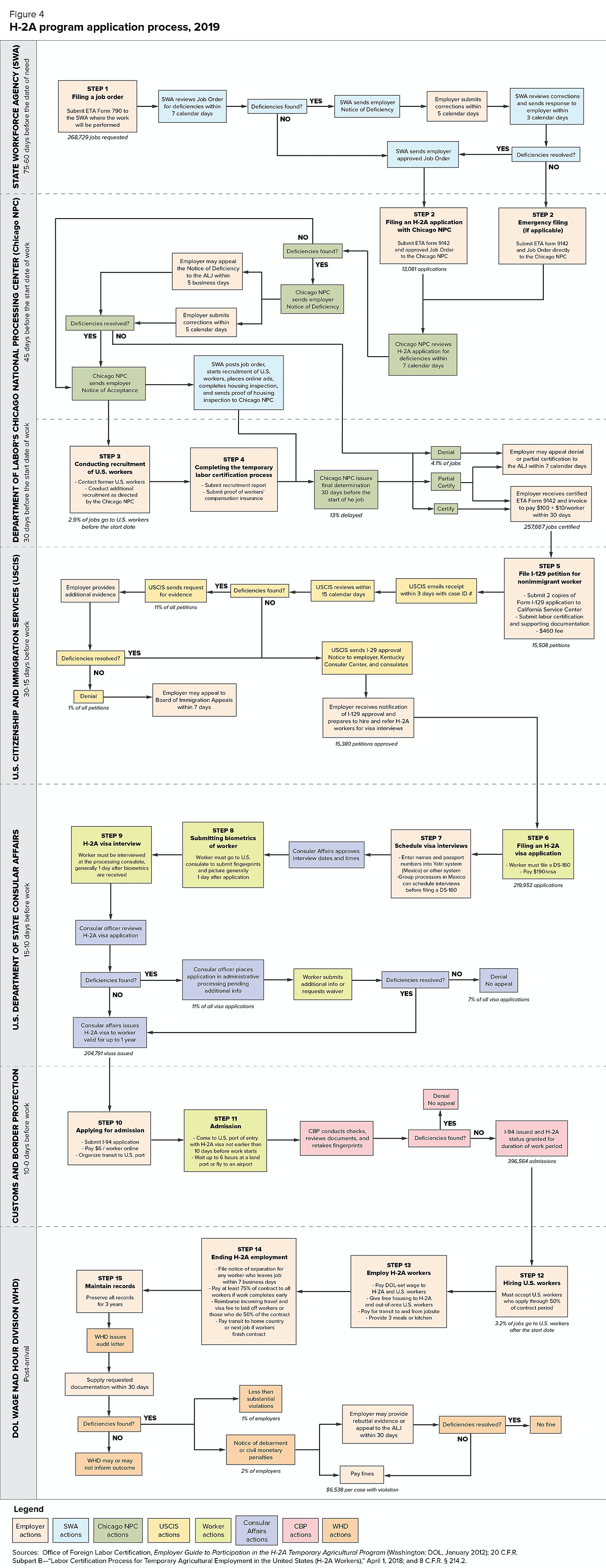

10 20 C.F.R. Subpart B—“Labor Certification Process for Temporary Agricultural Employment in the United States (H-2A Workers),” April 1, 2018.

11 8 U.S.C. 1188(c)(3)(A) (2018).

12 Government Accountability Office, Improved Guidance Could Reduce Employer Application Burden, p. 17.

13 Department of Labor, “Temporary Agricultural Employment of H–2A Nonimmigrants in the United States,” 84 Fed. Reg. 36,170 (July 26, 2019).

14 For 2006–2007, see Sen. Mike Crapo, “Letter to Hilda Solis,” March 14, 2012; for 2011 data, see Government Accountability Office, Improved Guidance Could Reduce Employer Application Burden, p. 12; for 2012–2019, see “Selected Statistics by Program,” OFLC Performance Data, Department of Labor, Employment and Training Administration.

15 No agency tracks whether workers show up on time. Government Accountability Office, Improved Guidance Could Reduce Employer Application Burden, p. 17.

16 20 C.F.R. § 655.163 (2019).

17 20 C.F.R. § 655.135(d) (2019).

18 8 C.F.R. § 103.7(b)(1)(i)(A) (2019); “I-129, Petition for a Nonimmigrant Worker,” Citizenship and Immigration Services, updated October 18, 2019. USCIS is proposing to change the fee structure to $425 per petition for unnamed beneficiaries and $860 for named beneficiaries. Department of Homeland Security, “U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services Fee Schedule and Changes to Certain Other Immigration Benefit Request Requirements,” 84 Fed. Reg. 62,308 (November 14, 2019).

19 “California Service Center Processing Time Report,” American Immigration Lawyers Association, March 19, 2018.

20 “I-129, Petition for a Nonimmigrant Worker,” Citizenship Immigration Services.

21 C.F.R. 214.2(h)(2)(iii) (2019); 8 C.F.R. 214.2(h)(5)(i)(F)(1)(ii) (2019). For the 2019 country list, see “H-2A Temporary Agricultural Workers: H-2A Eligible Countries List,” Citizenship and Immigration Services, updated January 24, 2019. The country list is based on four criteria: The country’s cooperation with respect to issuance of travel documents for citizens, subjects, nationals, and residents of that country who are subject to a final order of removal; the number of final and unexecuted orders of removal against citizens, subjects, nationals, and residents of that country; the number of orders of removal executed against citizens, subjects, nationals, and residents of that country; and such other factors as may serve the U.S. interests.

22 Ineligible countries in the Americas include Antigua and Barbuda, the Bahamas, Belize, Bolivia, Cuba, Dominica, Guyana, Haiti, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Saint Lucia, Suriname, Trinidad and Tobago, and Venezuela. “H-2A Temporary Agricultural Workers,” Citizenship and Immigration Services, 2015, https://web.archive.org/web/20160219155925/https:/www.uscis.gov/working-united-states/temporary-workers/h-2a-temporary-agricultural-workers.

23 “H-2 Visas,” U.S. Embassy and Consulates in Mexico.

24 Barbara Driscoll, The Tracks North: The Railroad Bracero Program of World War II (Austin: University of Texas, 1999), p. 58.

25 “The visa exemption for agricultural workers from the specified Caribbean countries dates back more than 70 years and was created primarily to address U.S. labor shortages during World War II by expeditiously providing a source of agricultural workers from the British Caribbean to meet the needs of agricultural employers in the southeastern United States.” Department of Homeland Security, “Elimination of Nonimmigrant Visa Exemption for Certain Caribbean Residents Coming to the United States as H–2A Agricultural Workers,” 81 Fed. Reg. 6430 (February 8, 2016).

26 8 U.S.C. § 1101(a)(15)(H) (2018).

27 Estimates are only recorded for air arrivals and departures, which comprise a small portion of the H-2A program. Government Accountability Office, Overstay Enforcement: Additional Actions Needed to Assess DHS’s Data and Improve Planning for a Biometric Air Exit Program, GAO-13-683 (Washington: GAO, July 2013), p. 17. More recent government reports only estimate the annual flow of people, ignore those who overstay, and don’t break these numbers down by detailed status. Department of Homeland Security, Fiscal Year 2018 Entry/Exit Overstay Report (Washington: DHS, April 2019). Outside analysis of the above report indicates that the estimates are too high and that the overstay population in the United States did not grow. Robert Warren, “DHS Overestimates Visa Overstays for 2016; Overstay Population Growth Near Zero during the Year,” Journal on Migration and Human Security 5, no. 4 (2017): 768–79.

28 “Disclosure Data, PERM Program,” OFLC Performance Data, Department of Labor, Employment and Training Administration.

29 8 C.F.R. 214.2(h)(5)(vii) (2019).

30 Customs and Border Protection, “CBP Reminds Travelers to Obtain the I-94 Permit Early,” news release, March 11, 2013; and Peter Samore, “Arizona’s Immigration Crisis: How Border Towns Are Impacted,” KTAR News, April 16, 2019.

31 20 C.F.R. § 655.122(i)(1) (2019).

32 United Fresh Produce Association, “In re: DOL Docket no. ETA–2019–0007, RIN 1205–AB89 Temporary Agricultural Employment of H–2A Nonimmigrants in the United States” 84 Fed. Reg. 36,168 (September 24, 2019).

33 “The higher of the AEWR, the prevailing hourly wage or piece rate, the agreed-upon collective bargaining wage, or the Federal or State minimum wage” under 20 C.F.R. § 655.120(a) (2019).

34 “Surveys—Farm Labor,” National Agricultural Statistics Service, Department of Agriculture, November 9, 2018.

35 20 C.F.R. § 655.10; 20 (2019); and C.F.R. § 655.731 (2019).

36 20 C.F.R. § 655.731 (2019).

37 “Adverse Effect Wage Rate Trends,” Office of Foreign Labor Certification.

38 David Bier, “H-2A Guest Worker Minimum Wages Up in 2020, 57% above New State Minimums,” Cato at Liberty (blog), January 3, 2020.

39 Benjamin Reist, Tyler Wilson, and Heather Ridolfo, Findings for the 2018 Agricultural Labor Base Wage Question Experiments (Washington: USDA, March 2019).

40 United Fresh Produce Association, “In re: DOL Docket No. ETA–2019–0007, RIN 1205–AB89 Temporary Agricultural Employment of H–2A Nonimmigrants in the United States,” 84 Fed. Reg. 36,168 (September 24, 2019).

41 David Bier, “H-2A Farmers Will Benefit from House Reform Bill,” Cato at Liberty (blog), November 5, 2019.

42 Bier, “H-2A Farmers Will Benefit From House Reform Bill.” Data are from: William G. Whittaker, Farm Labor: The Adverse Effect Wage Rate (Washington: Congressional Research Service, March 26, 2008), pp. 7–8; and “Adverse Effect Wage Rate Trends,” Office of Foreign Labor Certification, years 2009 through 2019.

43 20 C.F.R. § 655.122(i) (2019).

44 20 C.F.R. § 655.122(i) (2019); 20 C.F.R. § 655.122(d)(1) (2019); and C.F.R. § 655.122(g) (2019).

45 “‘I wish I could do [H-2A], but I need to build homes for them and that’s not cheap,’ said Marquez. ‘It’s too expensive for us to get that kinda help because the building that we have to have before we can put H-2A workers, their requirement is too high,’ said farmer Jose Rouna.” Quoted in Tristan Balagtas, “Local Farmers Struggling to Find Workers,” CBS News KIMA TV, August 1, 2019; “The hourly rate isn’t bad, but the housing and travel costs really increase the overall expense.” Quoted in Des Keller, “Seasonal Farm Workers Help,” Progressive Farmer, September 4, 2018; “The only ‘headache’ that comes with hiring H-2A workers, Davison said, is finding housing.” Quoted in Nicole Roy, “Temporary Workers Visa Program Grows in Western Idaho,” Idaho Press-Tribune, March 25, 2018.

46 Department of Labor, “Temporary Agricultural Employment of H–2A Nonimmigrants in the United States,” 84 Fed. Reg. 36,235 (July 26, 2019).

47 20 CFR § 655.122(h)(1).

48 8 CFR 214.2(h)(15)(ii)(C); (5)(viii)(B); (xii).

49 20 C.F.R. § 655.180 (2019).

50 These numbers exclude “sub-employer” certified jobs (secondary jobs for joint employers). For labor certification statistics 1989–1997, see Joyce Vialet, Immigration: The “H-2A” Temporary Agricultural Worker Program (Washington: Congressional Research Service, April 9, 1998); for 1998–1999, see Ruth Ellen Wasem and Geoffrey Collver, Immigration of Agricultural Guest Workers: Policy, Trends, and Legislative Issues (Washington: Congressional Research Service, January 24, 2003); for 2000–2004, see Philip Martin, Evaluation of the H-2A Alien Labor Certification Process and the U.S. Farm Labor Market (Silver Spring, MD: KRA Corporation, September 18, 2008), p. 42; for 2005–2015, see “Annual Performance Reports,” OFLC Performance Data, Department of Labor, Employment and Training Administration; for 2007, see p.25; for 2008 through 2011, see p. 35; for 2012 through 2015, see p. 4; for 2016–2019, see “Selected Statistics by Program,” OFLC Performance Data, Department of Labor, Employment and Training Administration.

51 For H-2A visa statistics for 1987–2018, see “Nonimmigrant Visa Statistics,” Department of State; for 2019 aggregated data, see “Monthly Nonimmigrant Visa Issuance Statistics,” Department of State, Bureau of Consular Affairs; for H-2A admissions from 1988 through 1992, see the links in the “General Collection” in Immigration and Naturalization Service, Yearbook of Immigration Statistics (Washington: DOJ, 1992); for years 1993 through 2017, see Department of Homeland Security, Yearbook of Immigration Statistics (Washington, DHS, 2019), Table 25; for 2018, see “Legal Immigration and Adjustment of Status Report Quarterly Data,” Department of Homeland Security.

52 Estimates are based on Bureau of Economic Analysis, SA27N Full-Time and Part-Time Wage and Salary Employment by NAICS Industry (Washington: BEA, 2018).

53 Office of Foreign Labor Certification, Employer Guide to Participation in the H-2A Temporary Agricultural Program (Washington: DOL, January 2012).

54 General Accounting Office, Improved Guidance Could Reduce Employer Application Burden, p. 33.

55 8 U.S.C. § 1188 (2018); and 20 C.F.R. § 655.100 (2019).

56 “Few U.S. workers were referred. . .” quoted in General Accounting Office, The H-2A Program: Protections for U.S. Farmworkers, GAO/PEMD-89-3 (Washington: GAO, October 1988); “The positive recruitment requirement appears to result in few domestic workers being placed in these jobs.” Quoted in Government Accountability Office, H-2A Agricultural Guestworker Program: Changes Could Improve Services to Employers and Better Protect Workers, GAO/HEHS-98-20 (Washington: GAO, December 1997), p. 58; “The H-2A certification process is ineffective,” quoted in Office of Inspector General, Consolidation of Labor’s Enforcement Responsibilities for the H-2A Program Could Better Protect U.S. Agricultural Workers (Washington: DOL, March 31, 1998); “Current recruitment procedures . . . produce few U.S. workers but lead to controversy and litigation,” quoted in Martin, Evaluation of the H-2A Alien Labor Certification Process, p. iv; Michael Clemens, “The Effect of Occupational Visas on Native Employment: Evidence from Labor Supply to Farm Jobs in the Great Recession,” IZA DP no. 10492 (Bonn: IZA Institute of Labor Economics, January 2017); Department of Labor, “Temporary Agricultural Employment of H–2A Nonimmigrants in the United States,” 84 Fed. Reg. 36,168 (July 26, 2019); “One agent for H-2A employers reported that its employer-clients had spent about $75,000 to advertise roughly 5,000 positions, and the employers did not receive a single applicant in response to the advertisements. An association representing agricultural employers similarly reported that its members spent millions of dollars on newspaper advertisements for H-2A positions each year and received no U.S. applicants in response.” Quoted in in Department of Labor, “Modernizing Recruitment Requirements for the Temporary Employment of H–2A Foreign Workers in the United States,” 84 Fed. Reg. 49,441 (September 20, 2019).

57 Steven Zahniser, J. Edward Taylor, Thomas Hertz, and Diane Charlton, Farm Labor Markets in the United States and Mexico Pose Challenges for U.S. Agriculture, Economic Information Bulletin no. 201 (Washington: USDA, November 2018), p. 2.

58 Michael A. Clemens, Ethan G. Lewis, and Hannah M. Postel, “Immigration Restrictions as Active Labor Market Policy: Evidence from the Mexican Bracero Exclusion,” American Economic Review 108, no. 6 (2018): 1468–87.

59 Clemens, “The Effect of Occupational Visas on Native Employment.”

60 Department of Labor, “Temporary Agricultural Employment of H–2A Nonimmigrants in the United States,” 84 Fed. Reg. 36,168 (July 26, 2019).

61 Author’s analysis of data in Department of Labor, “Temporary Agricultural Employment of H–2A Nonimmigrants.”

62 Department of Labor, “Temporary Agricultural Employment of H–2A Nonimmigrants.”

63 “Table A-14. Unemployed Persons by Industry and Class of Worker, Not Seasonally Adjusted,” Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2019.

64 “What Is Agriculture’s Share of the Overall U.S. Economy?,” Department of Agriculture.

65 “Census of Agriculture,” Department of Agriculture, National Agricultural Statistics Service.

66 “The National Agricultural Workers Survey,” Department of Labor, Employment and Training Administration.

67 “The National Agricultural Workers Survey.”

68 “Nonimmigrant Visa Statistics,” Department of State; and “Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages,” Bureau of Labor Statistics. (Inflation-adjusted using the Personal Consumption Expenditures Index.)

69 “Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages.”

70 “Census of Agriculture”; and “Selected Statistics by Program,” OFLC Performance Data, Department of Labor, Employment and Training Administration.

71 8 U.S.C. § 1101(a)(15)(H)(ii)(a) (2018).

72 Alex Nowrasteh and Andrew C. Forrester, “H-2 Visas Reduced Mexican Illegal Immigration,” Cato at Liberty (blog), July 11, 2019.

73 It is important to control for the amount of enforcement because more agents can cause more apprehensions without more total border crossings. Comparing apprehensions to admissions is more methodologically sound than comparing apprehensions to H-2A visas or H-2A jobs because the same worker can be admitted multiple times or apprehended multiple times. Immigration and Naturalization Service, Yearbook of Immigration Statistics (Washington: DOJ, 1992); Department of Homeland Security, Yearbook of Immigration Statistics (Washington, DHS, 2019); “Total CBP Enforcement Actions,” Customs and Border Protection, 2019, https://www.cbp.gov/newsroom/stats/cbp-enforcement-statistics-fy2019; Border Patrol, Nationwide Illegal Alien Apprehensions Fiscal Years 1925–2018 (Washington: DHS, 2019); Border Patrol, Border Patrol Agent Nationwide Staffing by Fiscal Year (Washington: DHS, 2018); and “Border Patrol Agents: Southern Versus Northern Border,” Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse, 2006.

74 Kevin Sieff, “Why Is Mexican Migration Slowing While Guatemalan and Honduran Migration Is Surging?,” Washington Post, April 29, 2019.

75 “Nonimmigrant Visa Statistics,” Department of State. The 2019 aggregated data are from “Monthly Nonimmigrant Visa Issuance Statistics,” Department of State, Bureau of Consular Affairs. For 1997–2017, see Department of Homeland Security, Yearbook of Immigration Statistics (Washington, DHS, 2019) (note that Jamaicans did not require visas until 2016 so the data on admissions were used for Jamaica only for 1997–2015).

76 Government Accountability Office, H-2A and H-2B Visa Programs: Increased Protections Needed for Foreign Workers, GAO-15-154 (Washington: GAO, March 2015).

77 Other reasons include Mexico’s relatively larger labor market, its more expedited consular visa processing, and its proximity to the United States, which can make it more affordable for employers to bus workers to the jobsites rather than fly them. Some border farms can also avoid paying for H-2A housing by allowing Mexicans to commute from their Mexican homes.

78 David Bier, “Trump Is Promising Visas for Guatemalans — Here’s How He Can Deliver,” Cato at Liberty (blog), August 2, 2019.

79 Rodolfo Benito Coy Garcia, quoted in Alana Semuels, “For U.S. Farmers and Mexican Workers, It’s Tough Being Legal,” Los Angeles Times, March 30, 2013; José Vásquez Cabrera, quoted in Ginger Thompson and Steven Greenhouse, “Mexican ‘Guest Workers’: A Project Worth a Try?” New York Times, April 3, 2001; Jacque Myburgh quoted in Jack Dura, “South African Workers Fill Mandan-area Farm, Ranch Labor Gap,” Associated Press, June 29, 2019; Joel, quoted in Brian Todd, “Who Harvests Your Food? Immigrant Labor a Growing Piece of Ag Workforce,” Forum News Service, August 8, 2019; Carlos Montano, quoted in Aaron Cerbone, “Migrant Labor in Gabriels,” Adirondack Daily Enterprise, August 17, 2019; and Jessie Higgin, “Farmers’ Struggle to Legally Import Workers Threatens U.S. Crops,” UPI, September 19, 2018.

80 “Selected Statistics by Program,” OFLC Performance Data, Department of Labor, Employment and Training Administration; and “Mexico Average Daily Wages,” Trading Economics, 2019.

81 The equivalent U.S. dollar amount for 88.36 pesos was $4.64 in 2019. See Secretaria de Gobernacion de Mexico, “Resolution,” December 2018.

82 University of California, Davis, “Farmworkers in Mexico’s Export Agriculture Conference Report,” Migration Dialogue, October 15, 2018.

83 “Orlando . . . supported his entire family, he said, and even if the wages in the U.S. dropped, he would still re-apply for a job as an H-2A worker. The money was too good to pass up. His roommate, Cesar, who would only his first name for the same reason, agreed with Orlando. ‘It’s the reason why we come,’ he added.” Quoted in Kate Cimini, “Could a Federal H-2A Visa Proposal Mean Lower Wages for Farmworkers? Advocates Worry,” The Californian, October 15, 2019.

84 Department of State, Nonimmigrant Visas Issued by Classification, Fiscal Years 2003–2007 (Washington: DOS, 2007).

85 Des Keller, “Seasonal Farm Workers Help,” Progressive Farmer, September 4, 2018; and Thompson and Greenhouse, “Mexican ‘Guest Workers.’”

86 “Human Trafficking on Temporary Work Visas: A Data Analysis 2015–2017,” Polaris, June 2018. From 2015 to 2017, 395,607 H-2A visas were issued: see “Nonimmigrant Visa Statistics,” Department of State. The Department of Homeland Security granted T status (for human trafficking victims) to 39 H-2A workers from 2009 to 2013, which represents 0.01 percent of H-2A visas issued. Government Accountability Office, Increased Protections Needed for Foreign Workers.

87 Milli Legrain, “‘Be Very Careful’: The Dangers for Mexicans Working Legally on US Farms,” The Guardian, May 16, 2019.

88 Unique employers were identified by eliminating duplicates in each year. Duplicates were identified after cleaning the data of punctuation and corporate structure identifiers that are commonly inconsistent. “Selected Statistics by Program,” OFLC Performance Data, Department of Labor, Employment and Training Administration; “Wage and Hour Division Compliance Action Data,” Department of Labor, July 26, 2019; and “Program Debarments,” Department of Labor, https://www.foreignlaborcert.doleta.gov/pdf/Debarment_List_Revisions.pdf.

89 The $2,836,551.51 in fines and 11,984 violations equals an average of $237 per violation. See “Fiscal Year Data for WHD,” Wage and Hour Division, Department of Labor, https://www.dol.gov/agencies/whd/data/charts.

90 “H-2A: Temporary Agricultural Employment of Foreign Workers,” Wage and Hour Division, Department of Labor, https://www.dol.gov/agencies/whd/agriculture/h2a.

91 Current regulations permit just 30 days for workers to find a new job under the H-2A visa (8 C.F.R. § 214.2(h)(5)(viii)(B)) (2019). See the comments of Giev Kashkooli of the United Farmworkers: Agricultural Labor: From H-2A to a Workable Agricultural Guestworker Program, Before the Subcommittee on Immigration and Border Security of the Committee on the Judiciary, House of Representatives, 113th Cong., 1st Sess. (February 26, 2013) (statement of Giev Kashkooli).