This visit could have an important impact on the U.S.-China trade relationship over the rest of President Trump's time in office. Past efforts by the Trump administration to deal with trade tensions have mainly focused on smaller trade irritants. Trump's visit to China is an opportunity to begin to address many of the larger U.S.-China trade conflicts.

Just prior to President Trump's meeting with China's President Xi in April 2017, which led to a “100-Day Action Plan” on trade under the framework of the U.S.-China Comprehensive Economic Dialogue, we published a Free Trade Bulletin making the case for a comprehensive Free Trade Agreement (FTA) as a way to address U.S.-China trade issues.2

We recognize that there is little political support for such an initiative at the moment. However, the alternative approaches that the Trump administration has tried so far are all insufficient. Unilateral threats from the United States are unlikely to accomplish much because domestic political constraints will prevent China from granting concessions for which it gets nothing in exchange. And the dialogue that led to the action plan has not produced significant results.

In our view, the failure of the action plan supports our earlier argument that a comprehensive FTA is the best approach to achieving a broad market opening in China. A number of the more difficult trade issues — intellectual property protection and technology transfer requirements, for example — require detailed rules and effective oversight of implementation. Only a binding set of rules, with an enforcement mechanism, can create the predictable and stable framework that U.S. businesses need.

In this paper, we explore in depth one particular issue covered by the action plan — access to the Chinese beef market — and use it to illustrate the need for an FTA. Removing the Chinese ban on U.S. beef was touted as a major achievement of the plan, but the reality is that there are many remaining obstacles facing U.S. beef exports. We describe below the high tariffs and regulatory barriers that remain and show that they can be addressed most effectively through a comprehensive FTA. If the United States really wants to address Chinese tariffs, nontariff barriers to trade in goods and services, and investment restrictions, it needs to push for the same kind of comprehensive FTA it has negotiated with other key trading partners. The upcoming visit by President Trump and Secretary Ross to China is the perfect opportunity to begin this process.

THE 100-DAY ACTION PLAN

The 100-Day Action Plan was instituted in April 2017, and in May treasury secretary Steve Mnuchin, commerce secretary Wilbur Ross, and Chinese vice premier Wang Yang announced an agreement on the initial list of items to be covered by the plan. President Trump touted the agreement by tweeting, “China just agreed that the U.S. will be allowed to sell beef, and other major products, into China once again. It is REAL news!” Secretary Ross called the deal “a new high” in the U.S.-China relationship, “pretty much a Herculean accomplishment,” and “more than has been done in the whole history of U.S.-China relations on trade.”3

The plan makes progress in a few areas, but the above statements exaggerate its impact. The plan covers 10 items, which address particular concerns of either the United States or China. Of the 10 items, 5 were concerns raised by the United States and 5 by China, ranging from trade in goods (beef, poultry, biotechnology products, liquid natural gas exports), to financial services, to symbolic gestures (America's recognition of China's “One Belt, One Road Initiative”). All the issues described in the plan have been addressed to some extent, but the plan's obligations were so vague and general that nominal fulfillment was easy and the actual impact on the market is difficult to assess.4

And the attempt to discuss larger and deeper issues at the follow-up meeting in July yielded no more than a phytosanitary protocol on trade in rice. The item on the list that seemed the most promising was opening China's market to U.S. beef. This development was touted by Secretary Ross as a great win, as he celebrated “a $2.5 billion market . . . being opened up for U.S. beef.”5

China fulfilled its commitment by signing a protocol with the U.S. Department of Agriculture, and the first shipment of beef was sent to China in June.6

The reality of U.S. beef exports to China is complicated, however, and the market may not be as open as some people hope. In the next section, we offer some background on the Chinese beef market, and the barriers U.S. producers still face there, in order to illustrate the limited impact of these kinds of narrow efforts at addressing U.S.-China trade conflicts.

CHINA'S BEEF MARKET

Traditionally, China has not been a big consumer of beef — pork and chicken were more common choices. However, due in part to strong economic growth, China's beef consumption has grown in recent decades; beef consumption has risen from 0.652 kilograms per capita in 1990 to 3.817 kilograms in 2015.7

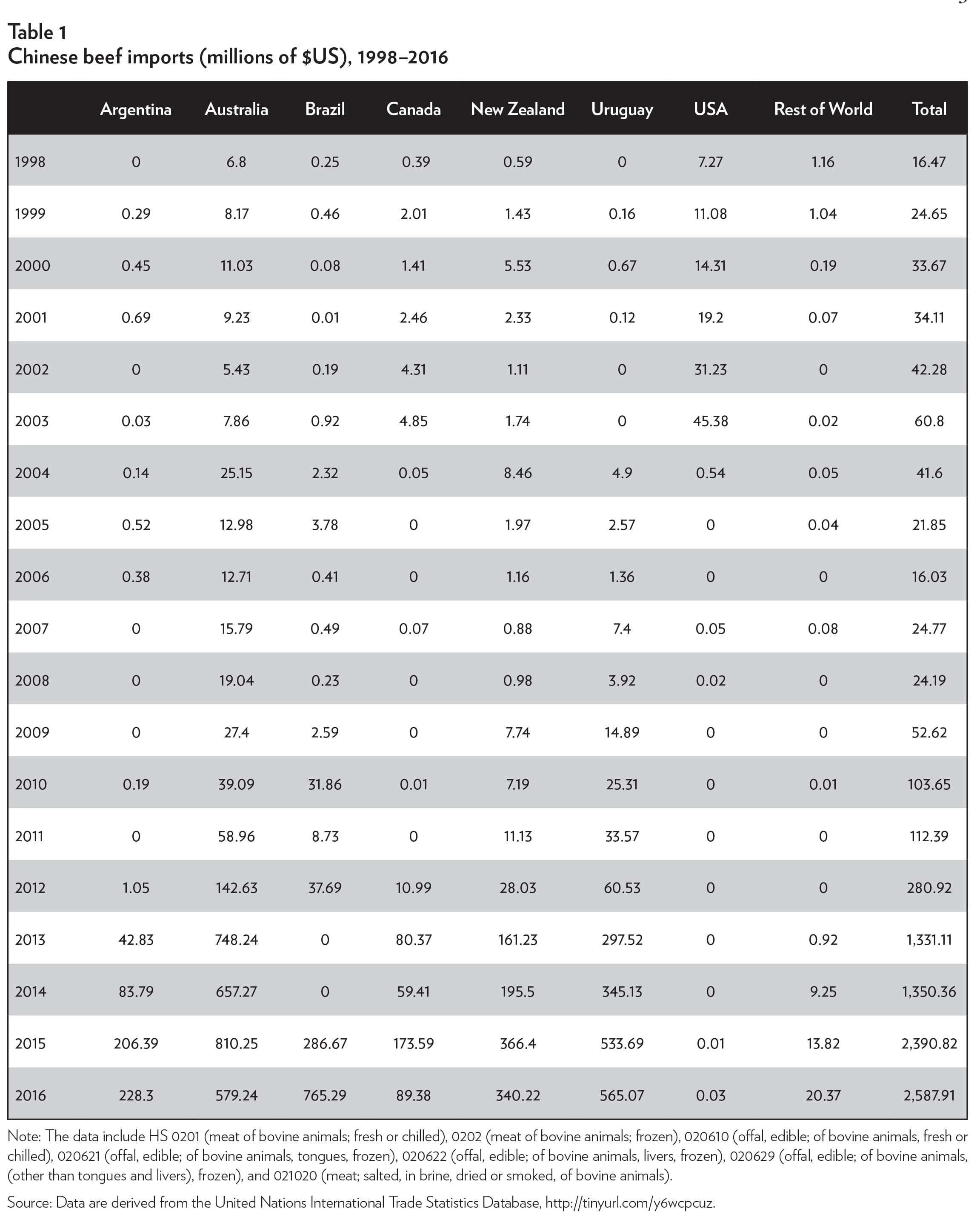

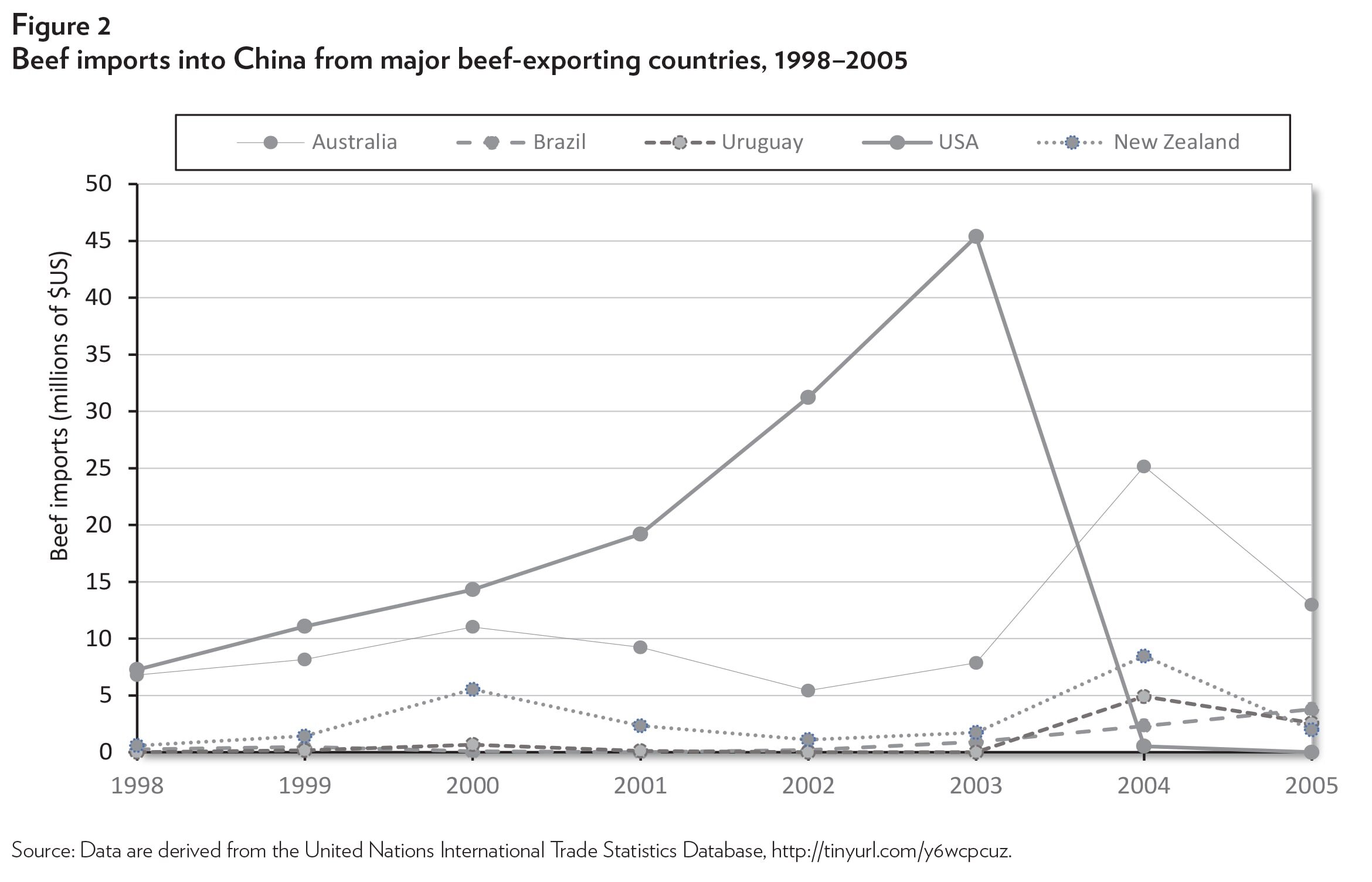

Over time, domestic production could no longer meet demand, and beef imports began to increase. Table 1 shows beef imports into China since 1998, by country. As shown in the table, China imported just $16 million worth of beef from all trading partners in 1998. That number jumped to $61 million in 2003, but imports declined in 2004 after an outbreak of bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE), also known as mad cow disease, in 2003. Imports increased again in 2009 and have continued to grow. In 2016, China's total beef imports exceeded $2.5 billion.

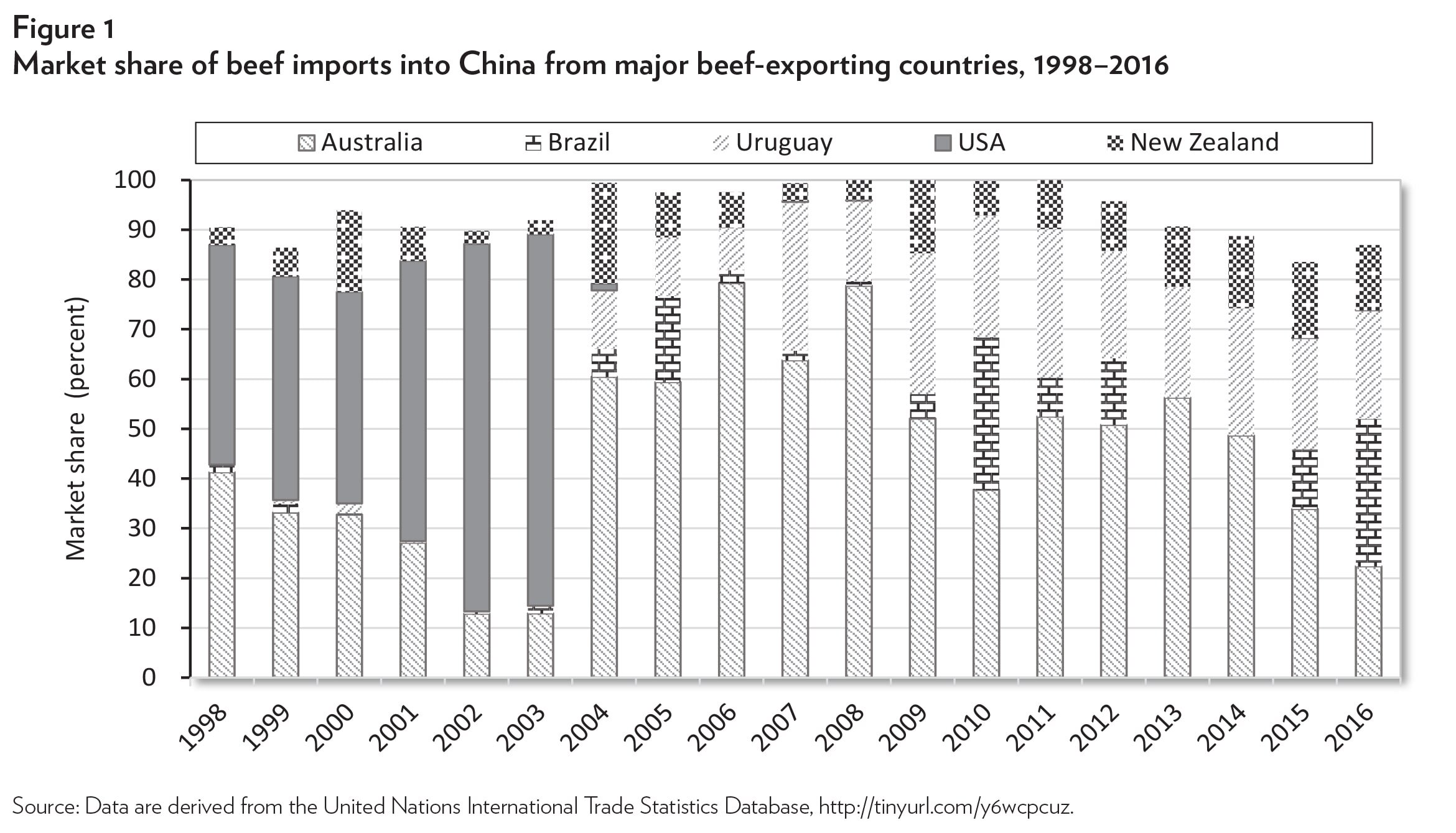

Figure 1 shows the share of imports into the Chinese market held by the major beef-exporting countries since 1998. U.S. exports dominated the market at the beginning of the period but almost completely disappeared after 2004 because of a Chinese ban on U.S. beef after the BSE outbreak. Since then, other countries have controlled the import market.

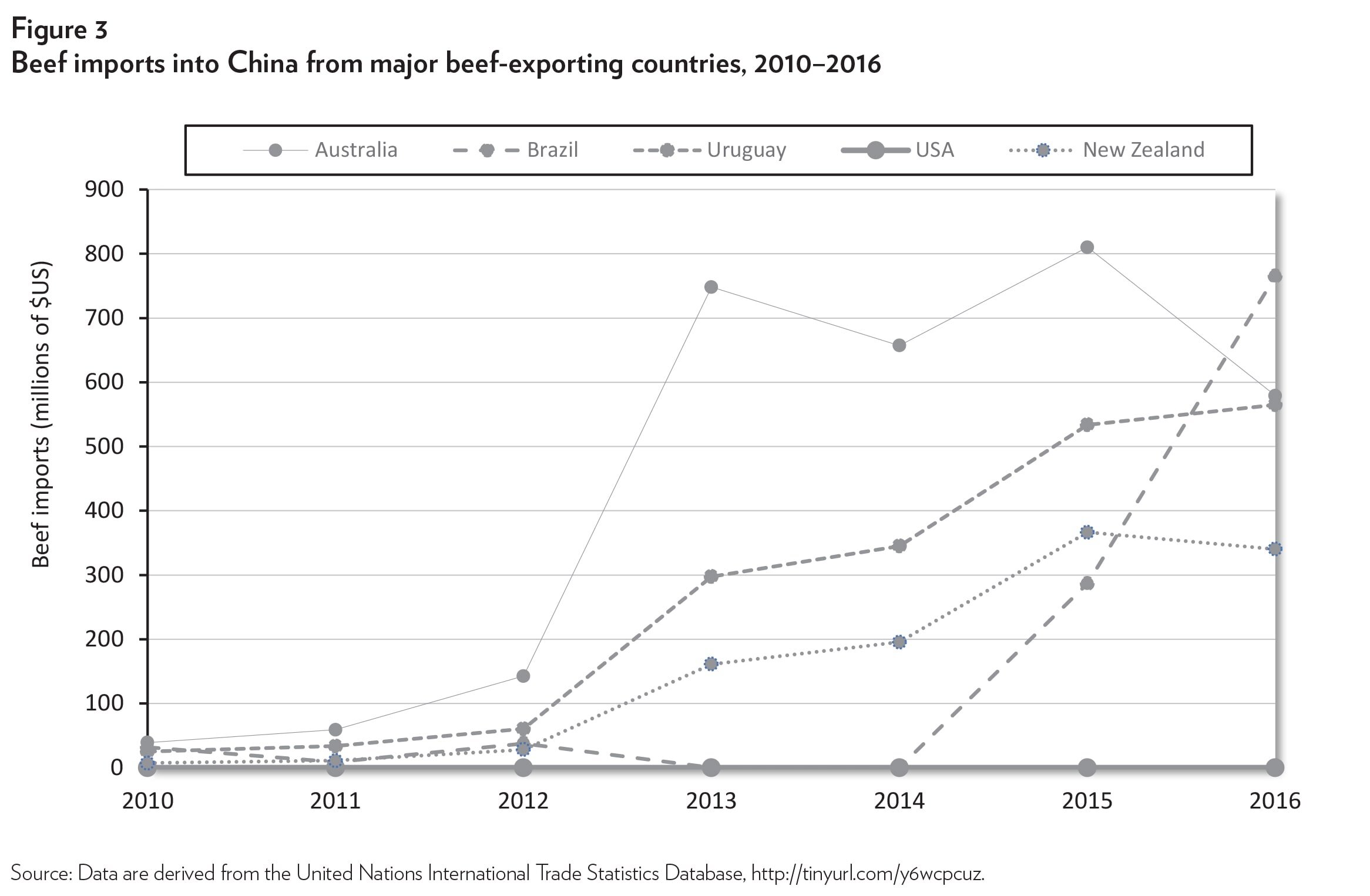

Figure 2 shows the early U.S. dominance of the Chinese import market (which was relatively small in terms of value at the time) and its quick decline after the BSE outbreak. Figure 3 shows the recent surge of beef imports into China from other countries as Chinese demand for beef increased.

What these figures show is the United States losing its market share over the years and other countries stepping in to take advantage of the increased Chinese demand. In 2003, U.S. beef had 75 percent of the Chinese import market (Australia was a distant second, at around 13 percent). However, as noted, the United States lost this market dominance when China banned U.S. beef due to the BSE outbreak in 2003. (Many other countries, including Australia, Japan, Russia, and South Korea, also banned or restricted some or all U.S. beef imports.8) The BSE outbreak had a more long-term impact on U.S. beef exports to China than it did on exports to other markets. While many countries halted U.S. beef imports at the start of the outbreak, China was particularly slow to reopen its market to U.S. beef.9 Instead, it turned to other major beef producers, including Australia, Brazil, New Zealand, and Uruguay, and these countries became China's main suppliers.

By 2016, China's largest import source for beef was Brazil, which quickly rose to being the number-one exporter to China (a 29 percent market share for imports) after China lifted a three-year ban on Brazilian beef in 2015.10 (This situation is likely to change due to a Brazilian beef scandal in March 2017.) Following Brazil are Australia and Uruguay, each holding 22 percent of the beef market; New Zealand and Argentina hold 13 percent and 9 percent, respectively; and Canada follows with 3 percent.

THE LIMITED IMPACT OF THE BEEF DEAL

There is little doubt the U.S.-China beef deal will boost U.S. exports to some extent. The U.S. has gained market access for all beef products, including chilled and frozen beef products, as well as scalded, heat-treated, and smoked beef. Many nations have more limited access. For instance, for various reasons Uruguay can only export frozen beef to China; Canada and Brazil can only export frozen deboned beef; and Argentina can only export cooked beef meat and offal and frozen deboned beef.11

Nevertheless, even with the ban lifted, it will take some time for the U.S.-China beef agreement to have an impact, and the effect on U.S. exports may be smaller than some have predicted. One reason is that Chinese consumers have been buying U.S. beef through a gray market despite the official ban, using Hong Kong as a transshipment point. The new legal U.S. beef exports to China may simply substitute for some of the current sales to Hong Kong.12

But more important, even with China's market now open, U.S. beef is at a competitive disadvantage compared to beef from other countries. Because there is no FTA between the United States and China, Chinese beef tariffs are applied to U.S. products at the World Trade Organization's mostfavored-nation rate. As a result, American beef faces a 12 percent to 25 percent tariff rate (depending on the specific product).13 In comparison, Australian beef currently faces a 4.8 percent to 17.5 percent tariff rate as a result of the China-Australia FTA. That tariff will be phased out sometime between 2019 and 2024 (depending on the product in question).14 New Zealand exporters already face zero tariffs because of the China-New Zealand FTA.15

In addition, Uruguay began negotiations on an FTA with China in 2016, and there is some potential for a broader Mercosur-China trade negotiation.16 Canada has also announced that it will launch an FTA negotiation with China.17 These FTAs, once concluded and implemented, will make it even more difficult for U.S. beef to compete with products from its main competitors.

U.S. beef exporters face nontariff obstacles as well, including restrictions on hormone-treated beef products. Some growth hormones are widely used in American feedlots.18 However, China adopted a regulation in 2002 that banned the synthetic hormones that are legal in the United States and also tightened the rules for beef treated with natural hormones.19 These restrictions limit the amount of U.S. beef eligible to be sold in China. (The U.S. Meat Export Federation estimates that roughly 3 percent of current production would meet China's requirements.)20 In contrast, South American countries do not use hormone treatments for their cattle.21

Finally, in order to be sold in China, U.S. beef must meet certain traceability requirements: beef products must be uniquely identified and controlled, and cattle must be traceable at each stage of production that has occurred within the United States.22 Right now, only 15 percent of U.S. producers meet these traceability requirements.23 In comparison, Australia, New Zealand, Uruguay, and Argentina all have mandatory traceability systems. Brazil does not have a nationwide traceability system but makes traceability mandatory for beef-export production.24

In sum, the U.S. beef industry will see some increased export sales to China as a result of the 100-Day Action Plan. But it will also face an uphill battle for market share due to the remaining barriers.

NEGOTIATING AN FTA

After the 100-Day Action Plan, the United States and China were supposed to start the negotiation of a one-year plan during the first Comprehensive Economic Dialogue on July 19, 2017. Unfortunately, that meeting did not yield any breakthroughs. The visit by President Trump and Secretary Ross to China in November will provide another opportunity for progress.

While it is helpful to address smaller lingering issues, such as those in the 100-Day Action Plan, putting these unconnected issues in simple and short declarations within a brief, unenforceable document does not constitute a broader trade strategy. Instead, the United States should consider negotiating a deep and comprehensive FTA with China.

An FTA negotiation will be an opportunity to address Chinese tariffs on beef and other products and to take on nontariff barriers as well. An FTA provides a stable and predictable legal framework, including an enforcement mechanism. It also offers a forum for future discussion of trade issues, including sensitive conversations about regulatory differences. For example, in the FTA negotiations (or subsequent discussions after completion of an FTA), the United States could try to convince China to drop its ban on hormone-treated beef.

Aside from beef, an FTA negotiation would create a starting point for the United States to bring China's laws and regulatory practices more in line with international norms on other issues, such as intellectual property protection, stateowned enterprises, technology transfer, cybersecurity, and cross-border data transfers. Intellectual property and technology transfer have been particular areas of concern, and in September, the Office of the U.S. Trade Representative initiated an investigation under Section 301 of the Trade Act of 1974 into these issues. There is no doubt that negotiations here would be difficult. However, just sitting down to talk in a serious manner could help each side better understand the other's perspective. And if an agreement could be reached in this area, it would pave the way for more trade and investment and lead to greatly improved relations between the two countries.

CONCLUSION

While the 100-Day Action Plan did constitute progress, China and the United States appear to be at an impasse again on trade, making the next steps unclear. The Trump administration needs to develop a more comprehensive approach to trade liberalization with China in order to accomplish something more substantial. The beef deal offers an illustration of the limited market impact of small deals. More fundamental and systemic issues, such as tariffs and the wide range of nontariff barriers, play a large role in international trade and cannot be resolved with quick meetings and dialogues.

In beef and other sectors, if the United States wants to achieve liberalization of the Chinese market, it needs to consider deeper engagement, and it must be willing to negotiate. An FTA negotiation presents an opportunity for the two nations to sit down and discuss tariffs and nontariff issues, exchange views, and make compromises. Some countries have already done this with China, and more are following their lead. When the rest of the world is negotiating trade agreements, American businesses will be better off if the United States is in the game rather than sitting on the sidelines.

NOTES

1. Department of Commerce Trade Mission to China, Export. gov, https://www.export.gov/Chinamission2017.

2. Simon Lester and Huan Zhu, “It's Time to Negotiate a New Economic Relationship with China,” Cato Institute Free Trade Bulletin no. 70, April 4, 2017, https://www.cato.org/publications/free-tradebulletin/its-time-negotiate….

3. Damian Paletta and Simon Denyer, “Trump, China Reach Preliminary Trade Agreements on Beef, Poultry,” Washington Post, May 11, 2017, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/wonk/wp/2017/05/11/trump-china-reac….

4. Aaron Kruse, “100-Day Deal Deadline Scorecard,” AmCham China, July 13, 2017, https://www.amchamchina.org/news/100-day-deal-deadline-scorecard.

5. Paletta and Denyer, “Trump, China Reach Preliminary Trade Agreements on Beef, Poultry.”

6. “China Takes Delivery of First Shipments of American Beef in 14 Years,” Reuters, June 23, 2017, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-china-usa-beef/china-takes-delivery-….

7. Data are derived from the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development Database, “Meat Consumption,” https://data.oecd.org/agroutput/meat-consumption.htm.

8. “Countries Move to Ban U.S. Beef,” CNN, December 23, 2006, http://www.cnn.com/2003/BUSINESS/12/23/japan.madcow.reax/; “US Beef Imports Banned in BSE Alert,” Daily Mail, http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-204628/US-beef-imports-bannedBS….

9. Mexico allowed these imports within the year; beef exports to Japan and South Korea resumed in 2006 and 2007, respectively, and Brazil, Israel, and Saudi Arabia lifted their beef bans in 2016. See United States Department of Agriculture, “Trade,” April 26, 2017, https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/animal-products/cattlebeef/trade/; United States Trade Representative, “USTR Success Stories: Opening Markets for U.S. Agricultural Exports,” March, 2017, https://ustr.gov/about-us/policy-offices/press-office/factsheets/2017/m….

10. “China-People's Republic of, Livestock and Products SemiAnnual, Chinese Consumers Substitute Burgers for Bacon in 2017,” U.S. Department of Agriculture, February 27, 2017, https://gain.fas.usda.gov/Recent%20GAIN%20Publications/Livestock%20and%….

11. “List of Countries or Regions that Meet the Requirements of the Assessment Review,” General Administration of Quality Supervision, Inspection, and Quarantine of the People's Republic of China, updated August 23, 2017, http://jckspaqj.aqsiq.gov.cn/xz/spxz/201303/t20130329_349307.htm.

12. Tom Hancock, “Trade Deal Whets China's Appetite for US Beef,” Financial Times, May 31, 2017, https://www.ft.com/content/acd521ae-404d-11e7-9d56-25f963e998b2.

13. “Duties by Country 2017,” U.S. Meat Export Federation, https://www.usmef.org/downloads/Duties-by-Country-2017.pdf.

14. Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, China-Australia Free Trade Agreement, http://dfat.gov.au/trade/agreements/chafta/official-documents/pages/off….

15. New Zealand Ministry of Foreign Affairs & Trade, New Zealand-China FTA Agreement, https://www.mfat.govt.nz/en/trade/free-trade-agreements/free-trade-agre….

16. “Uruguay Seeks to Advance FTA Talks with China,” China Daily, February 3, 2017, http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/business/2017-02/03/content_28092515.htm.

17. Marie-Danielle Smith, “Free Trade with China to Be Decided This Fall,” National Post, September 7, 2017, https://www.pressreader.com/canada/national-post-nationaledition/201709….

18. The FDA allows two types of synthetic hormones, trenbolone acetate and zeranol, as well as the naturally occurring hormones estradiol, progesterone, and testosterone, to be used in cattle. See U.S. Food & Drug Administration, “Steroid Hormone Implants Used for Growth in Food-Producing Animals,” https://www.fda.gov/animalveterinary/safetyhealth/productsafetyinformat….

19. “Veterinary Drug Maximum Residue Limits in Food of Animal Origin,” China Department of Agriculture, no. 235 Notice, December 24, 2002, http://www.lnciq.gov.cn/nsjg/sjch/ywcs/201202/P020120202420005927252.doc.

20. The information is from personal email exchanges between the authors and analysts with the U.S. Meat Export Federation, based on USMEF trade hearings and various industry estimates.

21. Michael J. McConnell and Kenneth Mathews, “Global Market Opportunities Drive Beef Production Decisions in Argentina and Uruguay,” April 1, 2008, U.S. Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service, https://www.ers.usda.gov/amber-waves/2008/april/global-market-opportuni…; “Growth-promoting implants, fed antibiotics and beta-agonists are not being embraced in South America as a result of widespread consumer concern.” Jason Ahola, “What U.S. Should Know about South American Beef Production,” Progressive Cattleman, February 24, 2014, http://www.progressivecattle.com/topics/management/6095-what-usshould-k….

22. Cattle born in the United States must be identified before leaving the place of birth. If imported from Canada or Mexico, they must be traceable to the first place of residence. If imported from Canada or Mexico directly for slaughter, they must be traceable to the port of entry to the United States. “Export Verification (EV) Program: Specified Product Requirements for Bovine — People's Republic of China,” U.S. Department of Agriculture, https://www.ams.usda.gov/sites/default/files/media/QAD1030AAEVProgramfo….

23. Megan Durisin and Jeff Wilson, “U.S. Beef Exports to China Closer to Restarting,” Bloomberg, June 12, 2017, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2017-06-12/u-s-beef-exports-toc…; “Economics and Trade Bulletin, Highlights of This Month's Edition,” U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission, June 2, 2017, https://www.uscc.gov/sites/default/files/trade_bulletins/June%202017%20….

24. “Beef Traceability: A Look at Programs around the World,” Cattle Business Weekly, September 21, 2016, https://cattlebusinessweekly.com/Content/Headlines/-Headlines/Article/B….