Seriously though, I think there is a lesson for school choice advocates in how elements of the conservative movement are responding to the Trump phenomenon. One healthy conservative response has been self-reflection and self-criticism, particularly concerning the effectiveness of conservative messaging and the importance of understanding first principles. That’s something school choice advocates should do as well.

What School Choice Supporters Can Learn from the Conservative Response to Trump

This is National School Choice Week and Donald Trump appears poised to capture the GOP presidential nomination. What do the two have to do with each other? Absolutely nothing. But it seems the only way to get any attention these days is to talk about Trump, and who am I to argue?

Perhaps the most concerning sign that large portions of the GOP base don't fully embrace or understand conservative principles was the poll showing that GOP voters' positions on key issues varied significantly depending on whether the pollster said that Trump supported it. Worse, the voters' fickleness was not confined to obscure issues like the Export-Import Bank or the Federal Reserve, but rather the most hot-button issues of the Obama presidency.

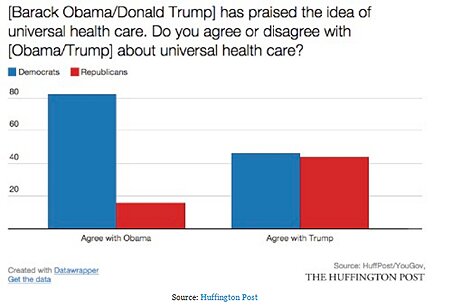

In the last seven years, no issue has so unified the GOP base as opposition to Obamacare, yet when told that Trump supported universal health care, Republican respondents' support rose 28 points compared to those who were told that Obama supported it. Now, in fairness, Democratic support for universal health care dropped 36 points when told that Trump favored it, so this problem is not exclusive to the GOP. Nevertheless, the apparent willingness of supposedly conservative voters to discard their principles so cheaply should be no less disconcerting.

Short of the wholesale abandonment of conservative principles, we also see prominent politicians who adopt seemingly conservative positions without fully understanding why. For example, when asked about the Second Amendment, Mitt Romney—who, as Jonah Goldberg noted, spoke conservatism as a second language—talked about being “a hunter pretty much all my life.” Likewise, when explaining his conversion to the pro-life cause, Trump told a story about a baby that was almost aborted but “grew up to be a ‘superstar.’”

As Hillary Clinton might ask: what difference does it make? Well, a lot actually.

If the Second Amendment is really about hunting rather than self-defense and denying the state a monopoly on power, then there should be no objection to restricting handguns or at least imposing long waiting periods. And if opposition to abortion stems from the potential of a child to become a “superstar” rather than a conviction that all human life is sacred, then there should be no objection to aborting children with mental disabilities.

Policy flows from principles. Policymakers who misunderstand the underlying principles are liable to mess up the policy. That’s why it’s so important that how we talk about the issues accurately conveys those underlying principles.

The school choice coalition is a rather big ideological tent, so it is not surprising that advocates often have very different reasons for supporting school choice. Some of the most common reasons include:

- Freedom: A free society should have an education system that respects and reflects that freedom. The government should not have a near-monopoly over what our children learn. Rather than assigning children to government schools based on their zip code, parents should have the freedom to choose their children’s schools.

- Economics/competition: Government services tend to be expensive, low quality, and not very responsive to the needs of citizens/customers, especially when there is a monopoly. School choice would foster healthy competition that would improve quality while reducing costs.

- Pluralism: America is a diverse society. In public schools, decisions are made through a political process that pits citizens against each other and produces winners and losers. School choice diffuses this conflict by allowing people to select schools that align with their values without forcing those values on others.

- Equality/civil rights: In our district-based school system, children are assigned to schools based on where their parents can afford to live. That means low-income children tend to be assigned to lower-performing schools, undermining equality of opportunity and widening the socio-economic gap between whites and minorities. School choice would help level the playing, especially for low-income minorities.

These are all noble reasons to support school choice. Some of them overlap considerably, and I believe most supporters are at least somewhat sympathetic to all of them. But again, policy flows from principles. How policymakers prioritize these principles can determine how they design the policies.

Milton Friedman, the godfather of the school choice movement, primarily emphasized the first two. However, today the emphasis is most often on equality and civil rights. Even Senator Ted Cruz, in announcing his legislation to create a universal education savings account program for Washington, D.C., called school choice “the civil rights issue of our era.”

Now, Sen. Cruz and other school choice advocates may just be following Arthur Brooks’ advice to “steal” the best arguments from one’s ideological opponents (e.g., not ceding “social justice” to the left). However, we must be careful that when importing such rhetoric, we do not also import faulty underlying assumptions.

The danger in emphasizing equality is that it often entails downplaying the importance of freedom and market competition. That, in turn, frequently leads to the adoption of policies intended to promote equality that restrict freedom and undermine not only the market process, but also the goal of equality itself. As Milton Friedman once said, “A society that puts equality before freedom will get neither. A society that puts freedom before equality will get a high degree of both.”

For example, in the name of equality, some school choice advocates larded up Louisiana’s school voucher program with all sorts of regulations. In order to prevent “creaming,” private schools that accept voucher students were required to adopt an open enrollment policy and hold a lottery when oversubscribed. In order to ensure the poor aren’t turned away for lack of funds, the private schools were forbidden from charging parents more than the value of the voucher. And to ensure the private schools these low-income students attend are good quality, the schools were required to administer the state test.

Unfortunately, these well-intentioned regulations may well have undermined the effectiveness of the voucher program. For the first time ever, a gold-standard study released this month found that the vouchers had a negative impact on student performance on the state test. Nearly every previous gold-standard study found a positive impact while one found no statistically significant difference.

What went wrong? We cannot yet tell for certain, but it appears that the regulations chased away the better private schools. Concerned about the heavy regulatory burden and low funding, two-thirds of Louisiana’s private schools chose not to participate. The third that did participate had significantly declining enrollment, whereas the non-participating schools were growing slightly on average, indicating that the participating schools may have been more desperate, and therefore more willing to jump through the state’s hoops.

The emphasis on equality came at the expense of freedom and competition. Parents are free to spend as much as they want on booze or cigarettes, but Louisiana forbids them from spending one red cent more on tuition than the amount of the voucher. And as any economist will tell you, price controls lead to shortages and obliterate the price signal that is essential to a functioning market, which is not in the best interests of anyone, especially the poor.

School choice advocates must learn from these mistakes and heed Milton Friedman’s advice. More than 15 years ago, Friedman warned that voucher programs with similar regulations were “too small a scale, and impose too many limits, to encourage the entry of innovative schools or modes of teaching.” Instead, he reminded us:

The major objective of educational vouchers is much more ambitious. It is to drag education out of the 19th century — where it has been mired for far too long — and into the 21st century, by introducing competition on a broad scale. Free market competition can do for education what it has done already for other areas, such as agriculture, transportation, power, communication and, most recently, computers and the Internet. Only a truly competitive educational industry can empower the ultimate consumers of educational services — parents and their children.

Ideas have consequences. If we want to get the policy right, we must elect policymakers who understand the principles.

Choose wisely.