In 2015, U.S. defense spending will be about $600 billion, or about 3.24 percent of GDP. The former figure would strike many Americans as sufficient, and a few would find it excessive.

Robert Gates once said, “If the Department of Defense can’t figure out a way to defend the United States on a budget of more than half a trillion dollars a year, then our problems are much bigger than anything that can be cured by buying a few more ships and planes.”

But hawks want you to focus on the latter figure, 3.24 percent: they believe that an arbitrary fixed percentage of national output should be dedicated to defense spending every year. For example, Mitt Romney and Bobby Jindal would peg defense spending at 4 percent of GDP.

Wall Street Journal columnist Bret Stephens would see that, and raise them. In his new book, America in Retreat, Stephens calls for sharply increasing “military spending to upwards of 5 percent of GDP.”

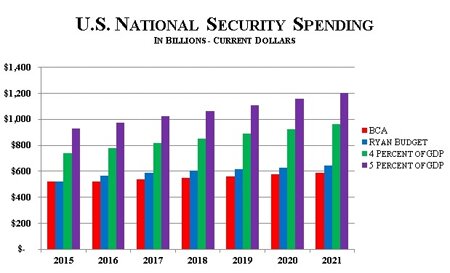

It’s unclear whether these gentlemen fully appreciate what their proposals would equate to in real dollar terms. (Take a look at the chart below, prepared by my colleague Travis Evans).

The bipartisan Budget Control Act (BCA) capped discretionary Pentagon spending at $3.9 trillion between 2015 and 2021, an average of 2.6 percent of GDP per year. That means Americans would need to spend $2.1 trillion above the current caps to meet the 4 percent threshold, and $3.6 trillion more to reach 5 percent.

For added perspective, then-House Budget Committee Chairman Paul Ryan’s FY15 alternative projected $4.2 trillion for defense, or 2.8 percent of GDP. In other words, Romney proposed to spend $1.8 trillion more than his running mate, and Stephens’s plan is even more disconnected from fiscal reality–$3.3 trillion more than the de facto GOP budget.

To justify their spending levels, hawks rely on imperfect historical analogies and threat inflation. Of course, it is true that the United States has spent more than 5 percent of GDP on defense in prior years and, at times, far more. President Dwight Eisenhower, who famously warned of a military industrial complex, presided over defense budgets that averaged about 10 percent; President Reagan averaged about 6 percent.

But, as I explain in a review of Stephens’s book in Barron’s:

While it’s true that military spending’s share of gross domestic product used to be higher than 5 percent, that was during the Cold War, when the U.S. was locked in a global struggle with the Soviet Union, and well before soaring entitlement spending threatened to overwhelm the federal budget.

If Stephens is serious about dedicating 5 percent of the nation’s economy to the Pentagon, nearly double what is called for under current law, cutting other federal spending won’t be enough to make up the difference. He never says whether he would hike taxes or add to a federal debt that is already out of control to pay for this global police force. But either way, taxpayer support is not likely.

That support is unlikely because U.S. foreign policy–and the military force structure needed to implement it–isn’t focused solely, or even primarily, on protecting the United States from foreign threats. Rather, our military aims to reassure nervous allies, and thus discourage them from defending themselves.

As Stephens puts it, “America is better served by a world of supposed freeloaders than by a world of foreign policy freelancers.”

This is a pretty flimsy justification for massive spending increases. From my Barron’s review:

Set aside the hubristic assumption that the U.S. government can be relied on to respond to distant threats more wisely and prudently than governments much closer to the problem. More broadly, Stephens is asking U.S. men and women to risk their lives in foreign conflicts, many of which have nothing to do with safeguarding American security.

He is also expecting Americans to pay for something they do not support. A recent poll reprinted in The Wall Street Journal in December 2014 pointed out that among the foreign-policy goals that Americans counted as “very important,” “defending our allies’ security” ranked second from the bottom, just one percentage point above “strengthening the United Nations.”

Instead of using an arbitrary percentage of national output to determine defense spending and expecting Americans to pay the bill without question, policymakers should develop a national security strategy that places a priority on U.S. national security, including the nation’s fiscal health, and demands appropriate burden-sharing by our allies.

America can maintain its military preeminence for decades if we reduce our military spending (or at least maintain the current caps), enact other reforms to get our fiscal house in order (including fixing entitlements) and allow our allies to better provide for their own security.