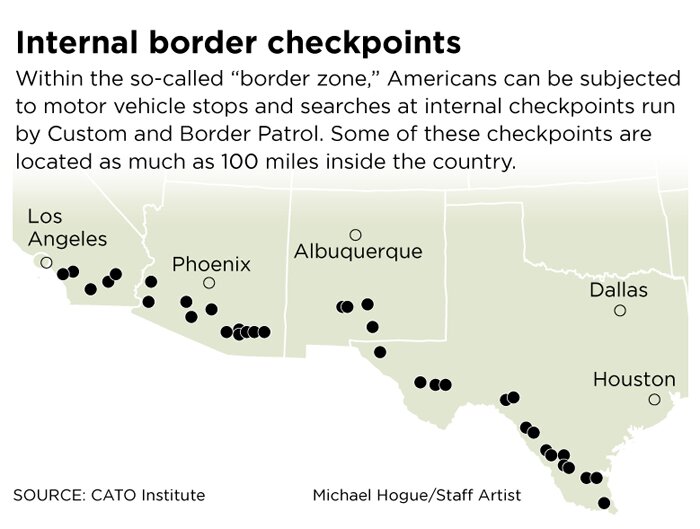

The Lone Star state has a rich history and cultural heritage, with many firsts to its credit. But there’s one not-so-glorious distinction bestowed upon this state by the federal government: Texas has more internal Customs and Border Protection checkpoints than any other state in the Union.

A new Cato Institute project, Checkpoint: America, provides the maps and related information to prove it. What it also provides are accounts of the naked brutality and disregard for constitutional rights that are also a feature of these checkpoints.

The case of Greg Rosenberg is a prime example. Rosenberg immigrated to the United States from Armenia during the first decade of the 21st century. Rosenberg grew up in what was then Soviet-occupied Armenia. Internal checkpoints were a key means of repression and control, just one of the many things Greg thought he'd left behind when he came to America and started his life here as a long-haul truck driver.

As chronicled by ReasonTV, Greg found out the hard way that Customs and Border Protection agents could be just as abusive as their former Soviet counterparts.

In late September 2014, Rosenberg found himself on Interstate 35 near Laredo. Like every other motorist, he was forced to pull over at the local Customs and Border Protection checkpoint. Rosenberg's complexion, and his accented English immediately drew the attention of agents. When Rosenberg asserted his rights not to answer the agents' questions, they dragged him from his vehicle and locked him up without charge for 19 days. No Customs and Border Protection official was ever disciplined for the incident.

Rosenberg's experience, as well as the back story on how these checkpoints came into existence, should enrage every American who believes in the right to travel freely without federal interference.

In 1953, a group of Justice Department bureaucrats got the bright idea that a key to immigration enforcement was allowing the federal government to set up internal checkpoints to try to catch illegal border crossers. A federal regulation was promulgated setting up a 25-mile interior zone in which such checkpoints could be established, all without public comment or debate. Years later, again without public input, the zone was increased to 100 miles into the United States.

Keep in mind that all throughout this period, no actual studies or real-world tests were conducted to see whether creating these interior checkpoints would be constitutional or effective. In 1976, the Supreme Court answered the first question in the affirmative, but in a split decision that remains controversial to this day.

The case, U.S. v. Martinez-Fuerte, sought to answer the question of whether Customs and Border Protection agents could stop any motorists for “brief questioning” (not further defined by the Court) to determine immigration status without meeting the Constitution’s Fourth Amendment requirement of probable cause that a crime was being committed. Amazingly, the majority of justices said Customs and Border Protection could, in fact, do exactly that — stop motorists without probable cause to quiz them as to whether they were U.S. citizens.

The majority argued that requiring Customs and Border Protection agents to meet the Constitution’s probable cause standard, or even the lower “reasonable suspicion” standard, would be “impractical” due to traffic volume. In their dissent, Justices Brennan and Marshall rebuked their colleagues, writing: “There is no principle in the jurisprudence of fundamental rights which permits constitutional limitations to be dispensed with merely because they cannot be conveniently satisfied.”

The Constitution, and particularly the Fourth Amendment, had been crafted to create a real, meaningful standard that government agents had to meet before seizing and searching Americans or their property. In the modern context, this included automobiles stopped in “roving checkpoint” searches, which the court had ruled unconstitutional just a year earlier.

Thus, the Supreme Court created two different standards for vehicle searches by the same federal agency. That legal schizophrenia has only made the problem worse over the last several decades, as a checkpoint search refusal movement has grown throughout the American southwest.

Texans, including veterans of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, have had to endure interrogations at these checkpoints. And as the Texas Observerreported earlier this year, Texan children have had their health and welfare placed at risk thanks to these checkpoints.

Observer reporter Elena Mejia Lutz chronicled the terror-filled journey of Diana, a child born in Laredo with scoliosis and no arms, whose undocumented mother was unable to find Laredo-area doctors who could help her manage her child’s condition. Diana’s mother managed to travel twice through a Customs and Border Protection checkpoint to take her daughter to Driscoll Children’s Hospital in Corpus Christi, but the fear of deportation and separation was always hanging over her head.

As Lutz wrote, the mother’s luck finally ran out. She was caught and deported in 2006, but returned across the border to Laredo to be with her American daughter. However, the fear of getting caught and deported again caused her stay close to home, and not make any further trips to the Corpus Christi hospital for 11 years. All the while, her daughter’s spine continued to curve unnaturally and painfully.

In July 2017, acting on rumors that Customs and Border Protection was letting undocumented parents travel with their sick, American-born children, the mother tried to get her daughter back to Corpus Christi for further treatments. Lucia was stopped and deported a second time.

“If she would’ve gotten surgery years ago and received better treatment, her back wouldn’t be curved at almost 360 degrees,” she told Lutz. “We were desperate because we couldn’t give her the help she needed. We could’ve given her a better life.”

As the story illustrates, the effects of these checkpoints on families can be painfully life-altering. The story also illustrates their ineffectiveness is keeping a determined mother from helping her disabled child.

Indeed, we have enough data now to demonstrate clearly that these checkpoints are not only ineffective in their stated mission — stopping illegal immigration — but have mutated into generalized crime control stops that disproportionately victimize Americans.

Last year, the Government Accountability Office issued a scathing report on Customs and Border Protection checkpoint operations. As my Cato colleague and economist Alex Nowrasteh observed about the findings, “Border Patrol checkpoints would have to have apprehended about 100,000 to 120,000 more illegal immigrants from FY2013-2016 than they actually did to justify the man-hours spent occupying them by agents. Even those who support expanding immigration enforcement along the border should recognize that checkpoints are a waste of scarce border security resources.”

So what are the checkpoints good at? Arresting Americans with dime bags of marijuana.

The GAO found that some 40 percent of the apprehensions at the checkpoints (about 40,000 between fiscal years 2013–16) involved “1 ounce or less of marijuana from U.S. citizens. In contrast, seizures at other locations were more often higher quantities of marijuana seized from aliens.”

To recap: if our national policy is to 1) minimize illegal border crossers, 2) minimize the flow of illegal drugs into the country, and 3) respect the Constitutional rights of Americans, a key step in improving all three would be to dismantle these internal checkpoints and immediately redeploy the Customs and Border Protection agents to the border. It’s a shame Texas Gov. Greg Abbott didn’t make that proposal to President Donald Trump before calling up the already over-worked and over-deployed Texas National Guard for border patrol duty.