While the Affordable Care Act (ACA) promises “quality health insurance coverage for all Americans,” a potential tradeoff exists between the law’s dual goals of promoting quality and preventing insurance companies from denying coverage or charging higher premiums to patients with preexisting conditions. This issue, which gets lost amid the partisan wrangling over Obamacare, could determine the fate of the law.

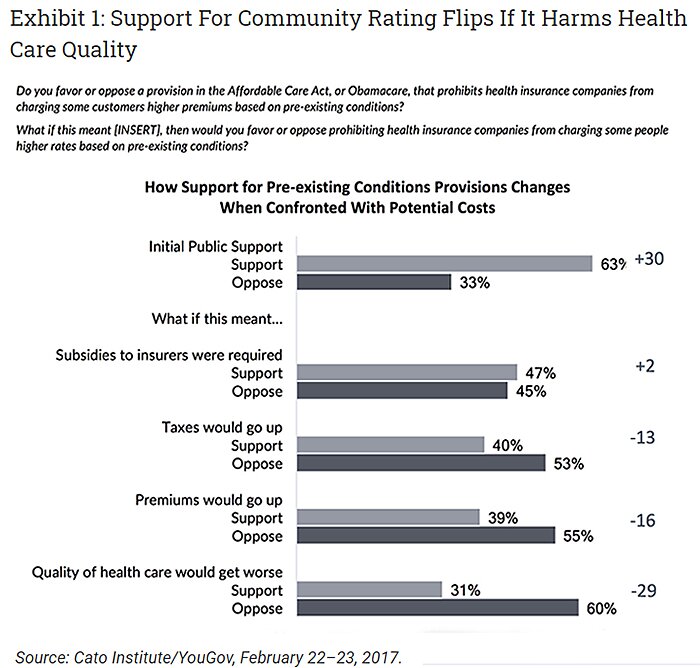

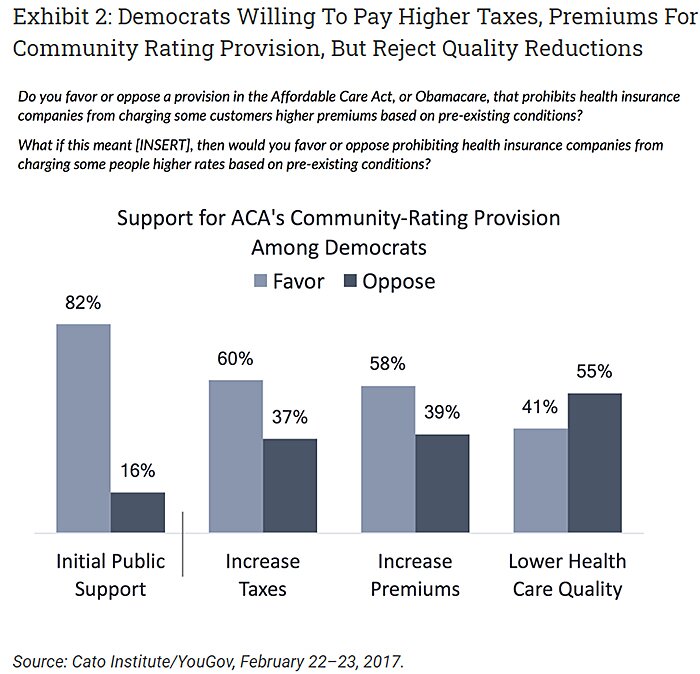

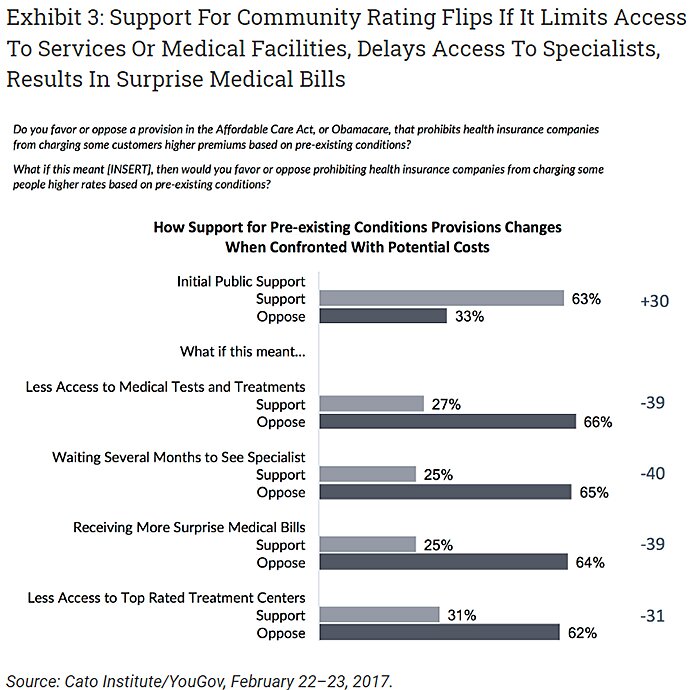

Public opinion surveys show voters support Obamacare’s preexisting conditions provisions by a two-to-one margin. If those provisions have the effect of reducing quality, however, that initial support flips to two-to-one opposition (Exhibit 1). The biggest shift is among Democrats, who swing from 82 percent in favor to 55 percent opposed (Exhibit 2). Voters turn against those provisions whether the erosion in quality comes in the form of less access to medical tests and treatments, longer waits for care, more surprise medical bills, or less access to top-rated treatment centers.

Research shows those provisions are indeed reducing quality along the very dimensions that concern voters, although interpretations differ on how significant those findings are. If Obamacare’s preexisting conditions provisions end up sacrificing quality, the health care debate could change dramatically (Exhibit 3).

Background

Obamacare’s preexisting conditions provisions literally penalize insurers that offer quality health insurance to the sick. That is not the purpose of those provisions, of course. Their purpose is to make health insurance available to the sick. They do so, in part, by requiring insurers to charge sick enrollees no more than healthy enrollees of the same age (and to do something similar when setting premiums across age groups). The result is that these provisions increase premiums for younger and healthier enrollees, and reduce premiums for older and sicker enrollees.

It is there the problem arises. When government requires insurers to set premiums at a level below the amount the insurer expects an enrollee will file in claims, that government-mandated price ceiling penalizes insurers that offer quality coverage to those enrollees. To illustrate, suppose insurers expect the average multiple sclerosis (MS) patient to file $61,000 in claims and Obamacare requires insurers to charge those patients a premium far below that amount—say, $10,000. If each MS patient brings an insurer $10,000 in premiums but costs them $61,000 in claims, then each MS patient an insurer attracts represents a $51,000 loss. Since MS patients care a lot about the quality of their coverage, they will find and enroll in whichever health plans offer the best MS coverage. The better the MS coverage an insurer offers, the more money the insurer loses.

Needless to say, this is not an ideal incentive structure. The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation explains that Obamacare’s preexisting conditions provisions create perverse incentives for insurers “to avoid enrolling people who are in worse health” by designing insurance policies to be “unattractive to people with expensive health conditions.” Indeed, those provisions create relentless incentives for all insurers to make their coverage for high-cost conditions worse than their competitors’.

Insurers can reduce the quality of coverage for the sick in countless ways, including many that lead voters to reject Obamacare’s preexisting conditions provisions: higher deductibles and copayments; narrow provider networks that exclude top specialists or “star” hospitals; mandatory drug substitutions; excluding coverage for certain drugs; frequent and tight preauthorization requirements; using coinsurance instead of copayments; poor customer service; ceasing to offer comprehensive plans; and so forth. Anything sick patients like, Obamacare’s preexisting conditions provisions punish. Anything sick patients hate, those provisions reward. Such quality problems have emerged in various markets where state and federal governments have imposed similar rules.

In theory, government subsidies can eliminate those perverse incentives. Obamacare’s “risk adjustment” and “reinsurance” programs provide subsidies to insurers that attract high-cost patients with the goal of ensuring that insurers receive the “right” price for each enrollee—that is, a price that matches those enrollees’ actual costs. Put differently, Obamacare’s preexisting conditions provisions distort the prices insurers receive for covering high-cost patients, then the risk-adjustment and reinsurance programs attempt to undistort those prices in the hope of counteracting the resulting incentives to make coverage worse for the sick. The risk-adjustment program is permanent. The reinsurance program expired at the end of 2016.

Screening In Contract Design: Evidence From The ACA Health Insurance Exchanges

Complaints from patient groups provide anecdotal evidence that the risk-adjustment and reinsurance programs may be falling short. Since 2014, a coalition of 150 patient groups has complained that insurers are making coverage worse to “dissuade patients…from enrolling,” and that this dynamic is so pronounced it “completely undermines the goal of the ACA.”

Economists Michael Geruso of the University of Texas–Austin, Timothy J. Layton of Harvard University, and Daniel Prinz of Harvard University have produced a study that backs up those complaints with empirical evidence. The authors found that Obamacare’s preexisting conditions provisions are indeed making coverage worse; the erosion in quality affects all enrollees; and it is all happening despite the risk-adjustment and reinsurance programs.

Geruso, Layton, and Prinz grouped patients according to the classes of drugs for which patients received a prescription. They then measured whether the risk-adjustment and reinsurance programs set the prices insurers received for patients in each drug class above or below the cost of the average patient in that class. The authors found that those programs were not getting the prices right when it comes to patients with MS and other illnesses.

MS patients enrolled in exchange plans, for example, filed an average $61,000 in claims. Even after risk-adjustment and reinsurance subsidies, insurers still received only $47,000 per MS patient, meaning Obamacare’s preexisting conditions provisions still penalize insurers $14,000 for each MS patient they attract. Those provisions also still penalize insurers for offering attractive coverage for infertility services (penalty: $15,000 per patient), substance abuse disorders ($6,000), diabetes insipidus or hemophilia A ($5,000), severe acne ($4,000), nerve pain ($3,000), and other conditions.

Insurers are responding to those perverse incentives, the authors found, by offering “poor coverage for the medications demanded by these patients.” Drug coverage for those conditions is getting worse relative to both employer-plan coverage of drugs treating those conditions and exchange-plan coverage of drugs treating other conditions. Evidence of poorer drug coverage includes higher cost sharing, more stringent prior authorization requirements, and more exclusions from drug formularies. Exchange plans impose higher cost sharing even for generic drugs treating those conditions. They “are ten times more likely than employer plans to require prior authorization or step therapy for a generic, and are about twice as likely to not cover a generic on their formulary.” Generics are relatively inexpensive. But the patients who use these generics are expensive, and such features deter them from enrolling in an insurer’s plan.

Geruso, Layton, and Prinz write that the impact of this erosion in coverage quality “can be economically sizable,” costing patients with these conditions thousands of dollars per year. Yet, the erosion affects all enrollees because even “currently healthy consumers cannot be adequately insured against the negative shock of transitioning to one of the poorly covered chronic disease states.” And this erosion in quality is occurring along at least one of the dimensions that cause voters to turn strongly against the law’s preexisting conditions provisions: less access to medical tests and treatments.

A Regulatory Failure Or Success?

One interpretation is that this study shows that, despite the risk-adjustment and reinsurance programs, Obamacare’s preexisting conditions provisions are creating a race to the bottom because those provisions still “penalize high-quality coverage for the sick, reward insurers who slash coverage for the sick, and leave patients unable to obtain adequate insurance.”

Geruso, Layton, and Prinz offer another interpretation. They claim their study shows that the risk-adjustment and reinsurance programs are a success. First, they explain, “For the vast majority of drug classes, our work shows that risk adjustment and reinsurance neutralize selection incentives: an insurer who attracts this particular group does not benefit or lose disproportionately relative to insurers who avoid the group.” The risk-adjustment and reinsurance programs are therefore “a big win for the ACA” because they “seem to be working quite well overall at matching revenues to costs and thereby protecting consumers from the types of perverse contract designs meant to avoid sick consumers.” Second, they argue that even where these programs fail to mitigate the perverse incentives the preexisting conditions provisions create to reduce quality, patients are still better off than they would be without Obamacare.

Cause For Alarm, Not Congratulations

It is difficult to argue that Obamacare is working well overall. The law promised to end discrimination against the sick without compromising quality. The authors examined just one area and found that the law is in fact reducing the quality of drug coverage in a way that affects all enrollees.

Moreover, this study sets a lower bound, not an upper bound, on how much Obamacare’s preexisting conditions provisions are reducing quality. The authors acknowledge that those provisions may be making coverage worse in ways their study cannot detect, and the erosion in quality may get worse very soon. Insurers may be able to identify pricing errors that occur within or across drug classes and make coverage worse for those patients in countless ways. The authors admit that they may be missing pricing errors within drug classes, for example, when they acknowledge that their data are not granular enough to confirm widespread complaints that Obamacare plans are making HIV coverage worse. They acknowledge that insurers may be able to use geography or demographics to identify patients for whom the risk-adjustment program sets the prices too low and make coverage worse for those patients. Finally, the authors acknowledge that because the reinsurance program expired at the end of 2016, the penalties Obamacare imposes on quality coverage for the sick will become substantially larger and more widespread.

Many Consumers Are Worse Off

It is also difficult to argue that Obamacare’s preexisting conditions provisions left all patients better off. Since Geruso, Layton, and Prinz use employer-sponsored plans as their controls, their results imply that, to the extent the availability of exchange coverage has caused workers to leave employer plans, Obamacare has left them with worse coverage. The share of the population in employer plans was the same in 2016 as 2013 (55.7 percent), but aggregate figures can hide significant churning of workers leaving employer plans for the exchanges. In 2012, the Congressional Budget Office projected that as a result of Obamacare, “in 2019, an estimated 11 million people who would have had an offer of employment-based coverage under prior law will lose their offer,” and “another 3 million people will have an offer of employment-based coverage but will enroll in health insurance from another source instead,” possibly exchange coverage. The Urban Institute has estimated Obamacare will spur 1.5 million “job-locked” workers to leave employer plans for the exchanges.

An additional 24 million people had individually purchased guaranteed-renewable coverage (HIPAA required all non-short-term individual market plans to be guaranteed renewable). Such plans protected enrollees from premium spikes if they developed expensive conditions, were more secure than employer plans for patients with expensive conditions, and faced incentives to make plans attractive to the sick as well as not to renege on their commitments to the sick. Hundreds of millions of Americans once had the freedom to enroll in guaranteed-renewable plans but lost that choice when Obamacare outlawed them. A study by McKinsey and Company for the Department of Health and Human Services shows provider networks in individual-market plans have narrowed significantly since 2013, when the breadth of networks reflected actual consumer preferences.

Obamacare may be better than what many enrollees had before. But that is no excuse for ignoring the arguably greater number of consumers for whom the law made things worse.

Conclusion

Obamacare is breaking the one promise voters appear to care about more than any other—its promise of quality health insurance coverage—and this failure is about to grow more acute. Considering how much voters appear to value coverage quality, all parties should probably spend more time focusing on this failing. In Part 2, I examine what Congress might do about it.