In the State of the Union address, President Obama endorsed a bill to raise the $7.25 federal minimum wage by nearly 40% over three years to $10.10 an hour in 2016. That would be an exact copy of what President Bush did on May 25, 2007, by signing into law a 40% minimum wage hike in three stages — from $5.15 to $5.85 on July 24, 2007, then $6.55 a year later and $7.25 on July 24, 2009. Have we not learned anything from what happened last time?

Nearly 20 million young people ages 16 to 24 were working before the first increase in the minimum wage went into effect in 2007, but that number fell to 16.9 million shortly after the final increase. The unemployment rate for teens jumped from 15% to 25%. All that might be dismissed as bad luck or bad timing were it not for what happened to the number of people earning less than the minimum wage.

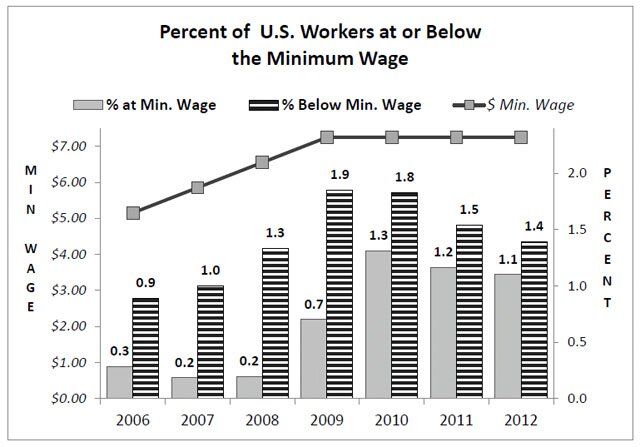

People are usually surprised to learn there are far fewer people earning the current $7.25 minimum wage than the number earning less than $7.25 an hour. In 2012, 1,566,000 people were paid the minimum wage in 2012, or 1.1% of all 142.5 million civilian employees, the Bureau of Labor Statistics says. In the same year, however, there were nearly 2 million people earning less than the $7.25 "minimum wage" — 1.4% of all jobs.

Since those 2 million obviously did not benefit from the last increase in the federal minimum wage, or from even-higher minimum wage rates in 23 states, why would anyone imagine they would now be paid more if the minimum were greatly increased again?

Minimum Wage Exemptions

The minimum wage law, under the Fair Labor Standards Act, does not prevent people from working at below $7.25 largely because of legal exemptions. All businesses with less than half a million dollars of annual sales are exempt (unless engaged in interstate commerce), as are seasonal amusement and recreational businesses, fisheries and small newspapers.

Many jobs are also exempt, such as home companions for the elderly, newspaper delivery people, babysitters, disabled workers, fishermen, switchboard operators. Independent contractors and some outside sales jobs are exempt. Tips often count against the minimum wage. And a minimum wage is virtually impossible to enforce for day laborers or housekeepers paid by the job in cash, or those paid on a piecework basis.

Whenever the federal minimum wage has been increased, the number earning less than the minimum wage has increased and the number earning the minimum has sometimes (notably in 2007) gone down.

At the time of the first 13.5% increase in the minimum wage in 2007 — before the recession began — the number of workers earning the minimum wage was nearly cut in half, falling from 409,000 in 2006 to 267,000 to 2007 (and still just 286,000 in 2008).

With additional increases in the minimum wage in mid-2008 and 2009, the number earning less than the minimum wage eventually doubled — rising from 1.28 million in 2006 to 1.46 million in 2007, 1.94 million in 2008 and 2.59 million in 2009. The recession explains some of the rise in sub-minimum-wage jobs, but not what happened in 2007 or why the number of sub-minimum-wage jobs remains close to 2 million.

The percentage of jobs that paid the minimum wage did finally rise in 2009 and 2010. The numerical increase mainly consisted of people who had previously earned more than the minimum, not less. Also, minimum wage employees were a larger fraction of all workers in 2010 than in 2007 because jobs had fallen by nearly 6.2 million.

Judging by what happened after the 2007–2009 increase in the minimum wage, repeating that failed experiment over the next three years would first reduce the number being paid the minimum wage and then greatly increase the number being paid less than the minimum. It would also result in millions more young people being unable to find any employment even at wages far below the higher minimum wage.

This is presumably not the effect salaried folks expect when they tell pollsters that another big increase in the minimum wage sounds like a terrific idea.