The most important price in an economy is the exchange rate between a country’s local currency and the world’s reserve currency, the U.S. dollar. As long as there is an active black market (read: free market) for a currency and data are available, changes in the black-market exchange rate can be reliably transformed into accurate measures of countrywide inflation rates. The economic principle of purchasing power parity (PPP) allows for this transformation. And, the application of PPP to measure elevated inflation rates is straightforward.

Evidence from Germany’s 1920–23 hyperinflation episode — as reported by Jacob Frenkel in the July 1976 issue of the Scandinavian Journal of Economics — confirms the accuracy of PPP during hyperinflations. Frenkel plotted the Deutschmark/U.S. dollar exchange rate against both the German wholesale price index and the consumer price index. The correlations between Germany’s exchange rate and the two price indices were very close to one throughout the period, with the correlations moving to closer to one as the inflation rate increased. In “The Measurement of Zimbabwe’s Hyperinflation,” which appeared in the Spring/Summer 2009 issue of the Cato Journal, Alex Kwok and I found that exactly the same relationships held in Zimbabwe’s 2007-08 episode of hyperinflation. This hyperinflation ranked second highest in world history — many times higher than Germany’s.

Beyond the theory of PPP, the intuition of why PPP represents the “gold standard” for measuring inflation for countries experiencing elevated inflation rates and/or hyperinflation is clear. All items in these economies are either priced in a stable foreign currency (the U.S. dollar) or a local currency. If goods are priced in terms of the local currency, those prices are determined by referring to the dollar prices of goods and then converting them to local prices after checking with the black-market spot exchange rate. Indeed, when a price level is increasing rapidly and erratically on a day-by-day, hour-by-hour, or even minute by-minute basis, exchange-rate quotations are the only source of information on how fast inflation is actually proceeding. That is why PPP holds, and why we can use high-frequency (daily) data to calculate inflation rates for countries with high rates of inflation, even during episodes of hyperinflation.

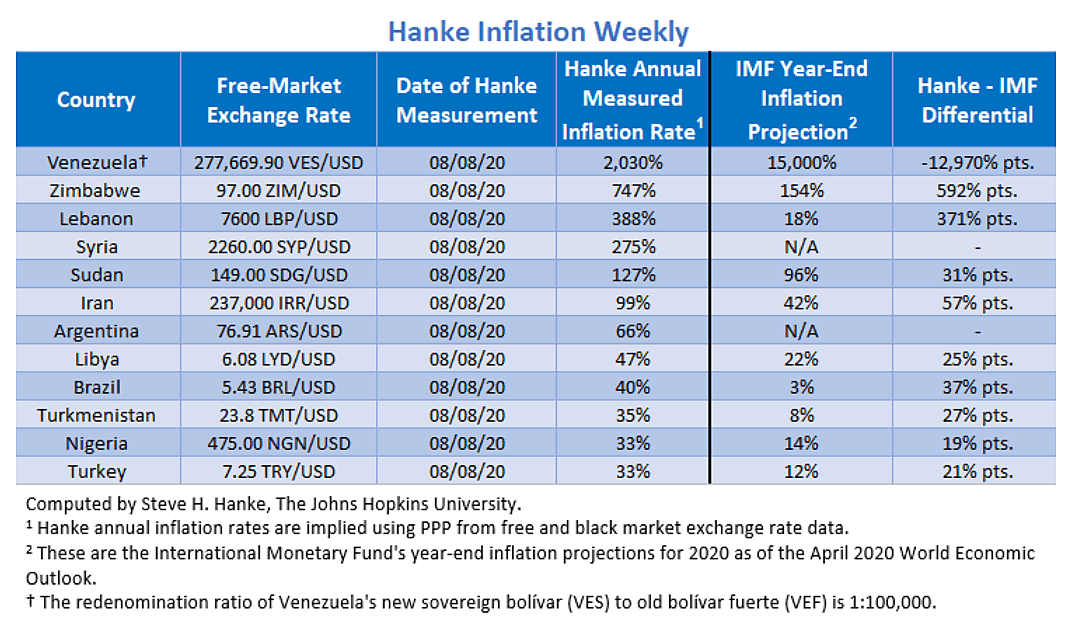

Each day, I use purchasing power parity and high-frequency data to measure prices in the countries with the world’s highest inflation rates. Below is my list of countries with annual inflation rates exceeding 25 percent per year.

It’s important to stress that by using PPP, I can measure high inflation rates with great accuracy, but no one can forecast the durations or magnitudes of episodes of hyperinflation or high inflation. Note in the table above that my measurement for Venezuela’s inflation rate is much lower than the widely reported International Monetary Fund (IMF) forecast. Also note the similar wide discrepancies between my measurements and the IMF’s forecasts for Zimbabwe and Lebanon. The IMF routinely attempts the impossible: to forecast inflation in high-inflation environments. Doing this only amounts to a finger-in-the-wind exercise that generates a great deal of useless, if not damaging, misinformation. Some highlights from last week’s inflation measurements follow.

Venezuela

Venezuela’s hyperinflation just keeps rolling along. Inflation spiked sharply in Venezuela last week to 2,030 percent per year, as the bolivar depreciated against the dollar by almost 12 percent in one week. With this, the bolivar hit a new all-time low against the greenback on August 6.

Lebanon

On July 22, 2020, Lebanon recorded 30 consecutive days in which the monthly inflation rate exceeded 50 percent per month. And, with that, Lebanon entered the record books with the world’s 62nd episode of hyperinflation and the first episode of hyperinflation in the Middle East North African Region (MENA). Last week’s massive explosion that destroyed Beirut’s port has drawn the world’s attention toward Lebanon’s corrupt leaders and dysfunctional government. But, international observers will once again, no doubt, focus on Lebanon’s hyperinflation — only the second ongoing hyperinflation in the world, alongside Venezuela’s.

Sudan

Sudan’s annual inflation hit 146 percent per year on August 4, marking its third highest annual rate of 2020 and its largest jump since April. Inflation is now 127 percent per year, a 20 percentage point increase from last week. Confidence in the pound has plummeted to its lowest value against the greenback since June 17.

Argentina

Despite Argentina’s deal with creditors to restructure $65 billion worth of government debt, investor confidence in Argentina remains low. The black-market exchange rate for the peso reached a new all-time low against the greenback last week, and inflation surged to 68 percent per year.

Turkey

Few believed me when I said the Turkish lira would hit 7.00 TRY/USD. But, on August 5, the lira passed that mark for the second time this year. Then, on August 8, the lira weakened further to 7.25 TRY/USD. And, as night follows day, the weakening of the exchange rate leads to higher inflation.