Dear Capitolians (I seriously need to retire this dumb gimmick),

I had planned this week to take a break from the wonkery and regale you with stories about nachos (no, seriously, I did), but the whole New York Post debacle has provided too good an opportunity to dig into one of the most misunderstood concepts on the internet (ironic, I know): Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act of 1996 and its relationship with internet companies like Twitter, Facebook and YouTube.

As you may have read here at The Dispatch (or elsewhere, I guess), a firestorm erupted last week when the New York Post published some rather, ahem, interesting and timely emails purportedly from Democratic nominee Joe Biden’s troubled son, Hunter Biden. Given the content of and events surrounding those emails, Twitter and Facebook decided to “moderate” that content—for example blocking the Post story (or websites linking to it) or posting warnings that users would have to click through to visit those same sites—in novel ways that hadn’t been applied to questionable content harming President Trump. Those actions, unsurprisingly, led to a total freakout on the right, including calls from prominent rabble-rousers and members of Congress that these companies have violated Section 230 and/or should (I kid you not) be “nationalized.” Now, the Federal Communications Commission is investigating whether to “clarify” (read: narrow) Section 230, and the Senate Judiciary Committee plans to make Twitter CEO Jack Dorsey testify later this week. The President, of course, has been his usual, calm self.

The whole thing was and remains a giant mess, and in my opinion the actions of Twitter/Facebook are stupid for myriad reasons (including by actually amplifying the allegations against them!). And I dare not even begin to opine on the veracity of the underlying claims. But I do think it’s good and necessary to spend a moment on a core element of the right’s current and longstanding claims about Section 230, and what would most likely happen if/when it’s repealed—something both the right and left now want.

So that’s what we’ll do today. (Before we go further, I should note that The Dispatch is a participant in Facebook’s fact-checking program.)

Why Section 230?

For a deeper dive into the origins of Section 230, I recommend this brief from my Cato Institute colleague Matthew Feeney. In short, the law was drafted to resolve a “Moderator’s Dilemma” emerging from 1990s court cases on whether online services can be liable for defamatory content that third parties (e.g., commenters) had posted on the services’ platforms. In one line of cases, CompuServe, which didn’t moderate content, was found to be not liable for alleged defamatory content because it was just a “distributor” of that content (like a public library) instead of a “publisher.” A few years later, Prodigy Services, which did moderate content, was held to be the “publisher” of (and thus was liable for) problematic third party content. Thus arose the “Moderator’s Dilemma”:

Either engage in content moderation and be considered the publisher of third party content or take a hands‐off approach to third party content and be treated like a distributor. Both options are awful for anyone interested in building a website where users can upload content. A hands‐off approach might save an Internet service provider from legal liability, but it also means users may upload pornography, photos of murders, and images of animals being tortured to death. To anyone trying to make a family‐friendly service, such a move has obvious downsides. Taking steps to remove such content may be desirable, but not if it means that your service is considered the publisher of third party content. Such an approach would require review [of] every third party piece of content before it appeared on the service. Needless to say, this effectively prohibits an Internet with useful third party upload functions and services.

If perfect content moderation was difficult in the 1990s, it’s all but impossible today: Facebook, for example, employs both artificial intelligence and around 15,000 humans to moderate “more than 100 billion pieces of content posted each day” to its platform, and it still struggles to screen that content effectively.

What Does Section 230 Actually Do?

Section 230 (47 U.S.C. § 230) solves the moderator’s dilemma by providing websites with both a “sword” and a “shield.”

-

Shield: Section 230(c)(1) overrules the Prodigy case: “No provider or user of an interactive computer service shall be treated as the publisher or speaker of any information provided by another information content provider.” These are the “26 words that created the internet” by codifying that websites (not just social media) can’t be considered the “publisher” of the vast majority of content that users upload.

-

Sword: Section 230(c)(2) applies to moderation: “No provider or user of an interactive computer service shall be held liable on account of (A) any action voluntarily taken in good faith to restrict access to or availability of material that the provider or user considers to be obscene, lewd, lascivious, filthy, excessively violent, harassing, or otherwise objectionable, whether or not such material is constitutionally protected; or (B) any action taken to enable or make available to information content providers or others the technical means to restrict access to material described in paragraph (1).” Thus, websites can’t be held liable for removing third party content, even if that content is protected by the First Amendment.

Together, these two provisions are widely credited with fueling the growth of not just social media, but essentially all internet businesses. Reason’s Elizabeth Nolan Brown explains why:

Section 230 stipulates, in essence, that digital services or platforms and their users are not one and the same and thus shouldn’t automatically be held legally liable for each other’s speech and conduct.

Which means that practically the entire suite of products we think of as the internet—search engines, social media, online publications with comments sections, Wikis, private message boards, matchmaking apps, job search sites, consumer review tools, digital marketplaces, Airbnb, cloud storage companies, podcast distributors, app stores, GIF clearinghouses, crowdsourced funding platforms, chat tools, email newsletters, online classifieds, video sharing venues, and the vast majority of what makes up our day-to-day digital experience—have benefited from the protections offered by Section 230.

Following the passage of Section 230, online business activity exploded. For example, the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis shows that the economic value created by “internet publishing” and the broader “ICT-producing industries” each increased around nine-fold (in real, inflation-adjusted terms) following Section 230’s passage in 1996.

For perspective: today the “internet publishing” industry alone is more than three times larger ($293.4 billion in real value-added in 2019) than the entire U.S. “primary metals” manufacturing industry ($79.3 billion), and “Big Tech” employs far more workers too. Surely, not all of this growth is attributable to Section 230—technology (faster internet speeds, the rise of smartphones, etc.) undoubtedly played a big role—but experts uniformly agree that Section 230 helped. A lot.

What Doesn’t Section 230 Do?

Conservatives and liberals don’t like Section 230 for a host of reasons, but few (if any) of them are accurate. So here’s a list of things that Section 230—contra the critics—doesn’t actually do:

-

Section 230 doesn’t subsidize Big Tech. First, Section 230’s liability protections in no way match any accepted definition of a subsidy (e.g., a government grant, tax break, low-interest loan, or free piece of land conditioned on a recipient’s identity or action), and the statute clearly doesn’t apply to only large tech companies. Second, and more importantly, this claim turns any sort of government protection into a “subsidy.” Is police protection a “subsidy” to small businesses? Are libel limitations “subsidies” to the media? What about anti-SLAPP laws (which protect individuals from frivolous lawsuits intended to silence them via the high cost of litigation)? If you’re a conservative and answering “yes” here, well, then you have bigger issues than Section 230.

-

Section 230 doesn’t distinguish between “publishers” and “platforms.” The most common form of this popular claim is that a social media company’s use of the content moderation “sword” magically turns it into a “publisher” that cannot utilize the Section 230 liability “shield.” The biggest error? The statute says no such thing (read it yourself). As Feeney notes, “Section 230 merely states that an interactive computer service is not the publisher of most third party content and is free to moderate content.” That’s it. Furthermore, this claim ignores that traditional “publishers”—like, say, the New York Post—also enjoy Section 230 protections when they host and moderate third party content (e.g., comments) online.

-

Section 230 doesn’t require websites to serve as a neutral “public forum.” This mistake is almost understandable for non-lawyers, as the “findings of Congress” in Section 230(a)(3) describe the internet and “interactive computer services” as “offer[ing] a forum for a true diversity of political discourse.” However, the mistake is unforgivable for actual lawyers like Senator Ted Cruz who know very well that such language is non-binding, and that the rest of the statute—including the actual definition of “interactive computer service” in Section 230(f)(2)—contains no such requirement. Furthermore, as TechDirt’s Mike Masnick and many others have noted, government requirements that private businesses remain politically “neutral” would be a blatant violation of their First Amendment rights.

Regardless, it’s also important to note that there’s not much evidence of systematic “censorship” of conservative views on social media. Sure, there are anecdotes or tweets from idiotic employees, but—as AEI’s Jim Pethokoukis’ recent review of the studies on this issue showed—the evidence of systematic bias is virtually non-existent. Both liberals and conservatives, moreover, clearly profit from and flourish (really) on social media—including by fighting with their online hosts. And, finally, liberals are just as mad about alleged social media bias against them. (Pro tip: when both sides are mad about “systemic bias,” chances are good that both are wrong.)

-

Section 230 doesn’t extend “special immunity” to social media companies that is denied to other media outlets. This one comes (unfortunately) from Federal Communications Commission Chairman Ajit Pai himself, but that doesn’t improve its quality. First, as already noted, Section 230 protects all internet companies, not just social media. Thus, traditional media outlets have the same Section 230 protections as Twitter and Facebook when it comes to hosting third-party content on their websites. Second, the statute establishes that internet companies are—just like other “media outlets”—still liable for their own speech; they’re just not liable for the speech of unaffiliated people posting there. Finally, it’s precisely the unique nature of online business in general (e.g., the need/incentive to allow third-party content, combined with the speed, ease and quantity of such content) and the resulting “moderator’s dilemma”—issues not shared by any other type of media or business—that necessitated Section 230 in the first place. NBC isn’t hosting a live open mic night out in front of 30 Rock anytime soon, and, even if they did, it’s pretty darn easy for them to “moderate” that “content” (same goes for radio or dead-tree periodicals). By contrast, internet companies (including legacy media ones!) have different needs, incentives, content, and problems. Hence, Section 230.

What Curtailing or Repealing Section 230 Might Do

As noted above, politicians on the right and the left, including both Biden and Trump, want Section 230 changed. Senator Josh Hawley, for example, wants 230 protections to be provided only to websites that are certified as “politically unbiased” by four of five Federal Trade Commission members. Others simply want it repealed. Not all of the proposed reforms are as draconian as these, but they all carry similar risks, including:

-

Putting the government more in charge of online speech. Whether it’s through the courts or through new administrative “certifications,” limiting or repealing Section 230 would inevitably result in more government regulation of speech, as subjective terms like “political neutrality” are applied or adjudicated by state actors. It’s frankly hard to see how this would be a win for conservatives in the long term.

-

Lawsuits. Lots and lots of lawsuits. AEI’s Jim Harper explains why:

It is very difficult at scale to review all the writings, pictures, videos, and links that millions or billions of users post. Stalkers, trolls, and other social maladaptives are incredibly wily and motivated, so a forgiving rule of liability for platforms seems best. If content is self-evidently wrongful or illegal—say, child porn that has already been algorithmically identified—legal responsibility for taking it down may lie with platforms. But if it takes interpretation or adjudication, responsibility for moderation could easily swamp a platform in potential liability.

Of course, the vast majority of internet speech isn’t “self-evidently wrongful or illegal,” and there’s an obvious risk of questionable lawsuits from questionable plaintiffs seeking cash from deep-pocketed tech companies.

A newly empowered plaintiffs bar for internet speech? What could go wrong?!

-

Reducing speech overall. Of course, the aforementioned litigation risks would inevitably affect internet companies’ behavior. As a Brookings Institution report recently explained, “proposals that seek to force platforms to engage in more monitoring—especially analysis before content is publicly available—will push internet firms to favor removing challenged content over keeping it. That’s precisely the chilling effect that Section 230 was intended to avoid.” Instead of more monitoring, internet companies might just close down comment sections altogether—precisely what Reddit and Craigslist did to certain at-risk pages in response to the 2017 Stop Enabling Sex Trafficking Act (SESTA), which eliminated certain Section 230 protections.

Long delays in, or strict internal regulation of, website commentary would also discourage use (who wants to wait a day to post a Tweet?), thus further chilling online speech. Maybe, having seen some of the nonsense regularly posted on Twitter (not by me, of course), you think less speech might actually be a good thing (I don’t), but recall that such policies would also apply to Amazon or Yelp reviews, or your silly birthday wishes on Facebook, or legitimate news and protest activity—all strangled by risk-averse companies now liable for any content that might possibly attract litigation. New restrictions on internet speech would also hinder benign efforts to use social media data for scientific and commercial initiatives, such as improving economic forecasting. All of this makes us worse off on balance.

-

Hurting consumers and small businesses (while helping Big Business). Regulation often hurts consumers and helps deep-pocketed incumbents at the expense of smaller upstarts, and Section 230 reform/repeal would likely be no exception. Brookings again:

Additional procedures, such as appeals for complaints and requirements to track posts, will increase costs for platforms. Right now, most popular internet sites do not charge their users; instead, they earn revenues through advertising. If costs increase enough, some platforms would need to charge consumers an admissions fee. The ticket price might not be high, but it would affect people with less disposable income. … Even if Twitter earns enough money to keep its service free, the regulatory cost of these proposals could make it harder for start-up companies to compete with established internet companies.

Rising costs would only worsen the antitrust and competition concerns that the Department of Justice and state attorneys general are already investigating. And there is no guarantee that reforms would justify their expense. Spam e‑mail didn’t dry up when the United States adopted anti-spam legislation in 2003; it simply moved its base of operations abroad, where it is harder for American law enforcement to operate.

Small companies would also be hurt by increased litigation costs. A recent survey found, for example, that fully litigating a single lawsuit can cost a company anywhere from $130,000 to $730,000 (or more!) in lawyer fees. Google and Twitter have in-house legal teams and can absorb these costs; new companies certainly can’t.

-

Empowering legacy media. As Reason’s Robby Soave explains, “[t]he demise of social media would limit the ability of people to express themselves on the internet, a venue where right-leaning speech has actually flourished: Facebook posts by Ben Shapiro, Fox News, Breitbart, and others are routinely the most-read content on the site. It is Trump’s great enemy, the mainstream media, which would benefit most directly from the collapse of these spaces for disseminating information.” Big win for the #FakeNews.

-

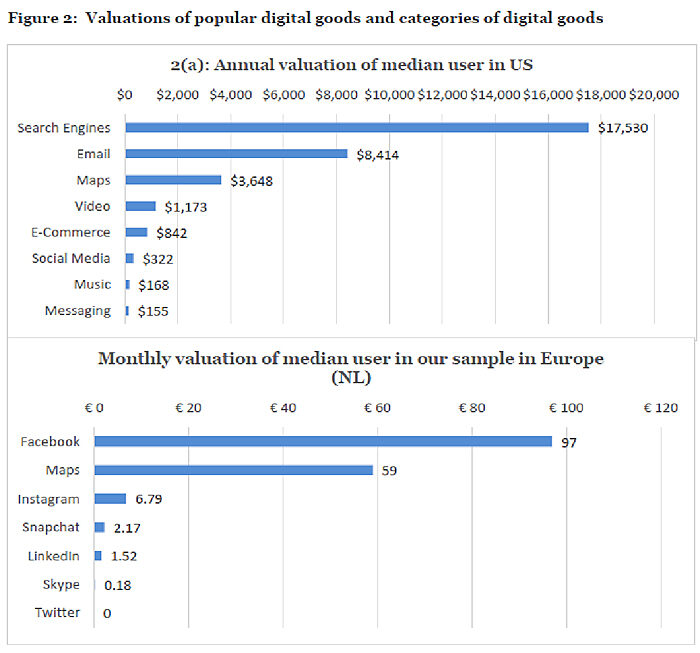

Slowing economic growth and innovation. Beyond the aforementioned new regulatory costs for consumers and small businesses, there’s also solid evidence of just how much Section 230 has benefited the U.S. economy over the last two-plus decades. For consumers, a 2019 study from Stanford’s Erik Brynjolfsson and others found substantial consumer benefits for free apps like Instagram, Snapchat, Facebook and LinkedIn, and that including the hidden welfare gains of Facebook alone would increase U.S. Gross Domestic Product by tens of billions of dollars each year. A separate Brynjolfsson study found that consumers place enormous value on digital goods in general (calculated by asking people how much money it would take for them to give up the service for a year):

Other studies have found similar welfare gains. Certainly, not all of these services would disappear without Section 230, but it’s impossible to think that their value to consumers—and that of any new services we haven’t considered—wouldn’t be reduced.

For companies and workers, a 2017 study found that eliminating liability protections for internet companies could kill $44 billion in U.S. GDP and 425,000 jobs each year, while discouraging investment in high-growth startups (due to the legal risks). A 2019 report compared the U.S. and (more restrictive) EU regulatory regimes, and found that due to Section 230 a U.S. internet company is “5 times as likely to secure investment over $10 million and nearly 10 times as likely to receive investments over $100 million, as compared to Internet companies in the EU.” Finally, a 2015 study found that stronger liability protections like Section 230 are associated with increased start-up success rates and profitability.

While some of these harms might not materialize if Section 230 were significantly curtailed or repealed (the First Amendment, for example, would still cover content moderation), it’s still essential to understand the risks before making major changes.

Summing it All Up

Obviously, I think Section 230 has been good law and oppose major changes to it. But here are few final thoughts for your consideration:

First, it strikes me that “Big Tech” is in a pretty unwinnable position here: on the one hand, their customers (e.g., ad buyers), users, and regulators demand that they moderate content (be it nudity, lies and deepfakes, hacked/stolen information, or whatever) and threaten to leave or regulate if the companies don’t take action; on the other hand, those same groups also threaten to leave/regulate when the same companies police content in a way the customers/users/regulators don’t like. Personally, I’d love for the companies to tell everyone to pound sand and regulate nothing except objectively illegal material, but I don’t have a business to run. And, given the unthinkable magnitude of information posted every minute online—along with the sketchy incentives for people (especially criminals and politicians) to abuse whatever “objective” system is in place—there seems to be no realistic solution to content moderation that’s going to keep these companies out of trouble.

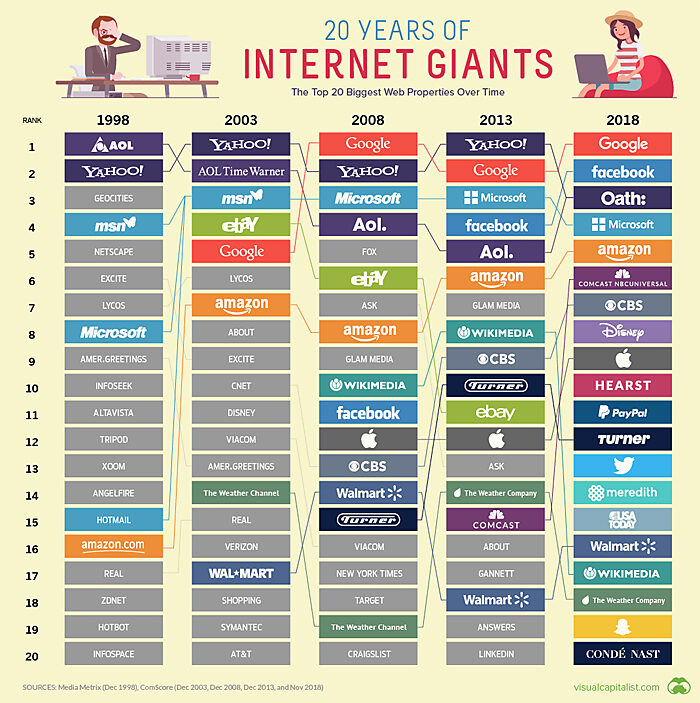

That said, I see little evidence that reform, particularly related to Section 230, is needed. Leaving aside the absurdity of calling unaffiliated competitors Twitter and Facebook a censorious “monopoly”—especially when doing so on their platforms!—there actually are plenty of options for online expression: Reddit (430 million users), Discord (250 million), LinkedIn (700 million), TikTok (800 million—well, until recently), Snapchat (300 million), etc. Then there are the legacy media websites (several of which are top internet traffic generators); the millions of podcasts and (ahem) newsletters; and, of course, “old school” TV, radio and newspapers. All of these companies (including Twitter) respond to market pressures, for better or worse, and can disappear as quickly as they arrive (headline from 2007: “Will MySpace ever lose its monopoly?”). Just look for yourself:

And, again, eliminating or reforming Section 230 would more likely strengthen the biggest internet players, rather than hobble them.

Finally, it strikes me as pretty nutty that the Party of Free Markets, Limited Government, and Economic Growth—one whose media ecosystem exploded upon the repeal of the Fairness Doctrine and one convinced of a #DeepState conspiracy against its Very Online leader (who routinely uses social media to bypass the #DeepState and the #FakeNews and has even relied on Section 230 to defend such behavior)—is now working to create a Fairness Doctrine for the internet and thereby hobble a thriving U.S. industry, stifle speech, grow government, and empower its mortal enemies because Twitter, Facebook and YouTube occasionally do stupid things.

But maybe that’s just me.

Chart of The Week:

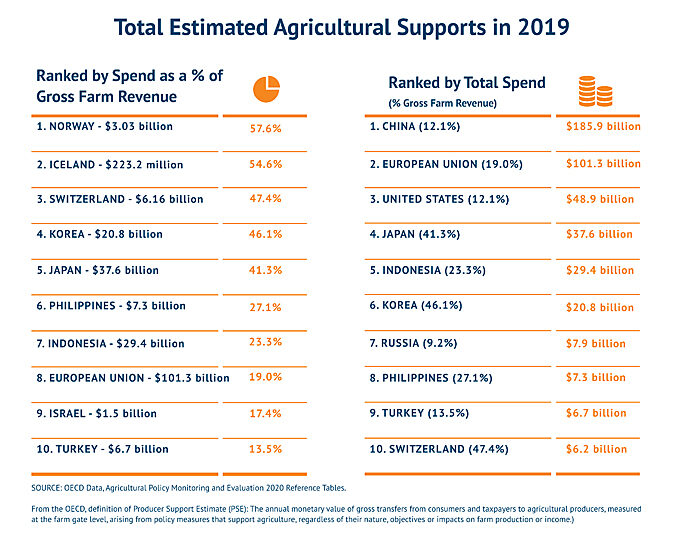

Farm subsidies are a global problem (except in New Zealand):

The Links

Me on the globalist COVID-19 vaccine and all those farm subsidies.

George Selgin’s detailed and critical look at the New Deal.

Kevin Williamson on America’s genius factory (and the fools who want to blow it up).

The USA ranks 21st on the latest Tax Foundation international tax competitiveness rankings.

The WSJ’s assessment of Trump’s economic record is similar to mine (but way too nice on trade).

Jim Pethokoukis on the GOP and Section 230.

How did US households use their Stimulus payments?

“A British supermarket launched a chicken nugget into space”