Dear Capitoli-stans,

I hope you had a great Thanksgiving and have successfully transitioned into the second- or third-best holiday season. (Thanksgiving is first, obviously, but it’s a photo-finish for second between Christmas and Independence Day. More on this later.)

As teased last week, we’re today going to examine a silver lining to COVID-19’s many dark clouds, but one that could be even brighter if it weren’t for misguided (at best) government policy. In particular, there has been an unexpected explosion of independent entrepreneurs and self-employed workers since the pandemic first destroyed much of the U.S. labor market. This recent Wall Street Journal deep dive provides the details and several neat anecdotes:

To adapt to the pandemic and the job loss it unleashed, more Americans are becoming their own bosses, setting up tiny businesses to work as traveling hair stylists, in-home personal trainers, boutique mask designers and chefs. A man in Maryland started a mobile car-washing business.

Many new entrepreneurs previously worked at salons, gyms and restaurants, in the kind of face-to-face jobs erased when state orders closed swaths of the economy in the spring. The economy has since mounted a split recovery, with some Americans thriving while many others continue to struggle. A cohort of the laid-off, stuck on the descending arm of that recovery, are using their ingenuity to get off it.

“As horrible as [the pandemic] is, and as badly as it has affected so many people, it has pushed people to come up with new ideas and products and services,” said Steven Hamilton, an economist at George Washington University.

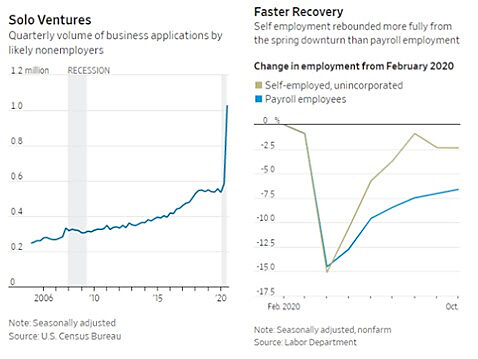

The data here, first noticed (I think) by University of Maryland economist John Haltiwanger, who specializes in entrepreneurialism and “business dynamism” (i.e., the process by which firms emerge, grow, contract, and fail), really are quite stunning. As the charts below show, there has been a dramatic spike in solo ventures and self-employment since the pandemic began, especially when compared to employment at established companies:

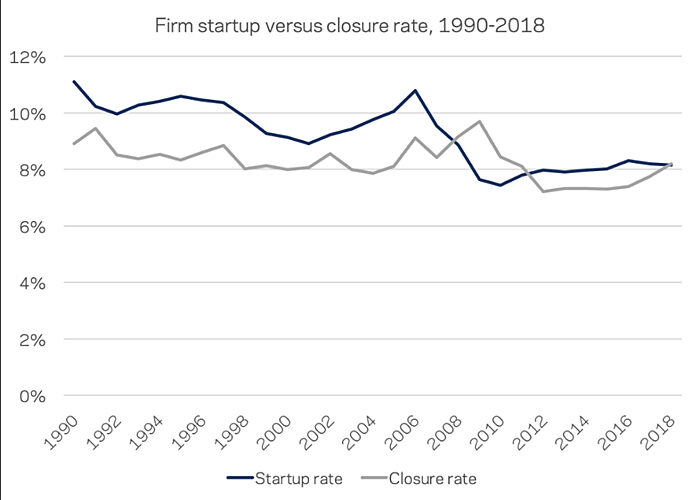

Other surveys reinforce these numbers, and the data are even more surprising given that business dynamism—particularly startup rates—in the United States has been slowing down during the last 30-plus years. According to the Economic Innovation Group, in fact, “the U.S. economy added no additional firms in 2018 [the last year of data available]—the first time on record this has happened during an economic expansion. Normally during periods of growth, the number of new firms spawned comfortably outpaces the number that are driven to close.”

Given that business dynamism is vital for productivity and economic growth, as well as the fact that startups disproportionately fuel job growth in the United States, economists have for years sought to figure out why new business formation has been so so lousy for so long here. Some of what they’ve found is relatively simple and unsurprising: For example, one recent paper concludes that the nation’s demographic trends (i.e., we’re getting older on average) explain much of the long-term decline in startup rates.

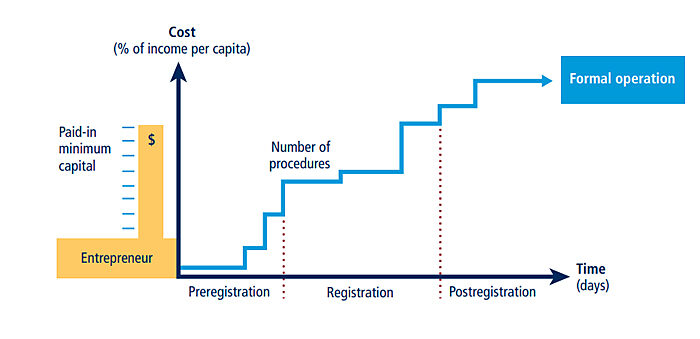

However, government policies (beyond those like immigration that would affect the aforementioned demographics) are also at play—policies that needlessly make it difficult for Americans to start their own businesses. For example, the World Bank’s latest Doing Business Report, which annually ranks nations’ legal and regulatory systems in terms of ease of running a business, finds that the United States ranks a paltry 55th in the world—far behind countries like New Zealand (1), Canada (3), Australia (7), and the U.K. (18)—for “starting a business,” which measures the number of procedures, time, cost, and paid-in minimum capital requirement for a small company to start up and formally operate in each economy’s largest business city. The following graphic shows the entire process examined:

The World Bank helpfully notes, citing the latest economics literature, that (1) regulatory reforms that make it easier to start a business have been found to encourage new firms, more employment, and higher productivity; while (2) overly cumbersome regulation of startups is associated with high levels of corruption and informal work. And the United States ranks an embarrassing 55th in this regard. Ouch.

(Granted, the World Bank report is based on starting a business in New York City, but a similar U.S. ranking puts it in the middle of North American cities in terms of starting a business. So it’s actually pretty representative of what we’re dealing with here.)

Covering all of the ways that federal and state laws might inhibit business formation and dynamism is way beyond the scope of a single newsletter. Simple fixes—such as reducing fees and paperwork—are obvious places to start, and, as indicated above, immigration liberalization could increase U.S. entrepreneurship rates (but that’s not really relevant for native workers and COVID-19).

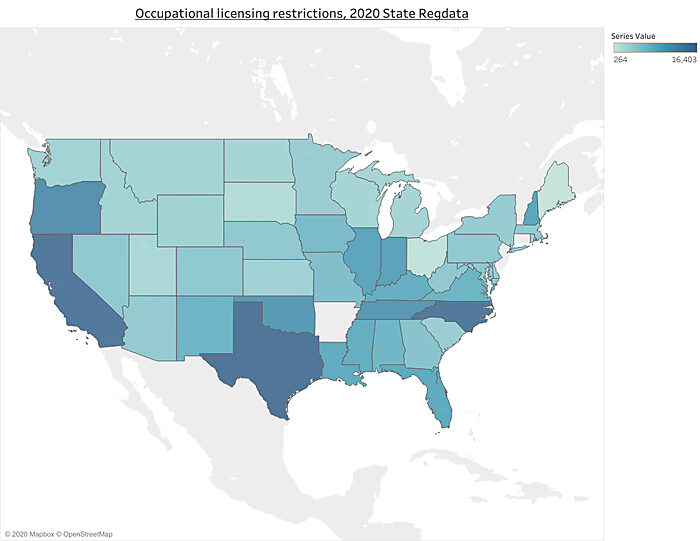

I want to focus today on just one key area: occupational licensing. Over the last 60 years, the number of jobs requiring an occupational license (or similar government approval to work in a profession), has grown from about 5 percent to almost 30 percent. Back in the Good Ol’ Days, states pretty uniformly required that only doctors, lawyers, and a few other professions have a certain training and licensure to operate in the state. Today, however, that same handful remains regulated across all states, but about 1,000 other occupations are also licensed—a number that varies widely from state to state and often without interstate reciprocity (thus creating not only a headache for workers but a serious barrier to their interstate migration, something this D.C.-licensed lawyer once learned the hard way when moving to North Carolina).

Some of this regulatory expansion stems from legitimate concerns for the health or safety of consumers in new fields or ones that have revealed new risks: By creating a state-regulated monopoly for certain services, so the theory goes, its quality will improve and its workers will be more committed to the field (having invested time and money to gain required education and skills). However, as the Institute for Justice (which litigates some of the most egregious licensing regulations on behalf of Americans blocked by them) explains, licensing rules often have little connection to legitimate consumer welfare concerns, with training for low-risk fields (e.g., cosmetology) often far exceeding high-risk ones (e.g., nursing). Instead, “licenses are most often created in response to lobbying by those already at work in an occupation and their industry associations” because licenses enrich incumbent workers and allow them to block new entrants into the field.

Regardless of the motivation, the end result is clear: The percentage of workers today subject to licensing in the supposedly “low regulation” United States is at or above the level in many European nations (and about the same as the EU average).

The licensing that American workers need does not come easily or cheaply either, even though the jobs themselves often don’t pay well. IJ calculated in 2017 that lower-income occupational licenses require, on average, nearly a year of education or experience, one exam, and more than $260 in fees. That might not sound like a major barrier to you and me, but it can be impenetrable to, say, a single parent living paycheck-to-paycheck or someone who just lost a job due to COVID-19.

These averages, moreover, mask the most onerous and absurd licensing cases—many of which have been successfully challenged by IJ and similar legal organizations: having a lemonade stand; lawn mowing; analyzing traffic lights (unlicensed engineering!); giving dietary advice; teaching with a license from another state; arranging flowers; offering home funeral services; and, of course, braiding hair.

This high and increasing level of licensure has obvious implications for employment in the regulated professions at issue: Licensing laws supposedly intended to benefit consumer health and safety often end up creating—through testing, training, and fees—onerous barriers to employment for workers who don’t actually pose a risk to consumer health and safety (the supposed basis for licensure). That’s especially a problem in the United States, given that our social safety net is designed for flexibility, not stability (like, say, Germany).

These licensing barriers, of course, apply to self-employment too and could be hurting Americans’ attempts to change careers—out of necessity or opportunity—during the pandemic. Indeed, several of the jobs mentioned in the initial Wall Street Journal article above on COVID-19 entrepreneurialism require licenses in one or more U.S. states. And the economic literature finds—again and again—that licensing severely burdens workers and their ability to change jobs (“labor dynamism”), while providing little benefit to consumers. For example, one recent paper examined license variation among the U.S. states and found that shifting an occupation from unlicensed to licensed reduces employment in the licensed occupation by a whopping 29 percent. The authors also discovered that licensing requirements delay the entry of younger workers into the relevant occupations, far beyond the amount of time needed to meet any relevant education requirements. Another study finds that licensing has significant negative effects on occupational mobility when switching both into and out of licensed occupations, accounting for “at least 7.7 percent of the total decline in occupational mobility over the past two decades.” Another paper looked specifically at the state cosmetology boards that determine licensing criteria and found many of them to be captured by incumbent license holders and (likely for that reason) erecting higher barriers to getting a license in that state.

Licensing requirements have been found to be particularly harmful for entrepreneurs without a lot of time and money. According to a 2015 paper from the Goldwater Institute, in fact, higher rates of state licensure of low-income occupations (barbers, manicurists, interior designers, various construction workers, taxi drivers, etc.) are strongly associated with lower rates of low-income entrepreneurship:

[S]tates that license more than 50 percent of the low-income occupations had an average entrepreneurship rate that was 11 percent lower than the average for all states, and the states the [sic] licensed less than a third had an average entrepreneurship rate that was about 11 percent higher.

These results, of course, make perfect sense, given the cost—time and money—of obtaining a license, or the risk of getting caught operating a business without one. The harmful effects of licensure on aspiring entrepreneurs and self-employed workers are magnified for individuals with a criminal record, which often bars potential applicants from obtaining a license and can thus thwart worthwhile “prison entrepreneurship” programs intended to rehabilitate inmates and decrease recidivism. Only a few states earn good grades in this regard, even though states with heavier occupational licensing burdens have been found to have higher recidivism rates than those with lower barriers to entry, while states with the fewest barriers actually saw recidivism rates decline. As shown in the anecdotes above, moreover, military spouses are also disproportionately affected by state licensing rules, given the type of work they often do and their families’ frequent interstate travel.

Fortunately, there’s some hope here. First and foremost, states like Arizona, Missouri, California, Iowa, Florida, and South Dakota have begun to act, either by enacting permanent reforms that recognize licenses from other states or by making it easier to get a license (including for people with criminal records). Governors across the country (and across party lines) have also voiced support for licensing reform, so hopefully more systemic reforms are on the way. COVID-19 has also caused many states to temporarily suspend “never needed” regulations to improve their pandemic response, including licensure requirements for not only health care workers (either expanding services that licensed nurse practitioners may provide or by recognizing out-of-state licenses) but also several other occupations. (A comprehensive list of these moves is available here.) These “emergency” exceptions should be made permanent.

Finally, there’s bipartisan support at the federal level for occupational licensing reform, which has been championed by the Obama administration, the Trump administration, and President-elect Biden. Although most licensing regulations are at the state level, there is an opportunity for federal action, for example the FTC’s work to educate the public on licensing rules and its specific antitrust actions against anti-competitive state licensing boards (as a result of the Supreme Court’s decision in North Carolina State Board of Dental Examiners v. Federal Trade Commission). Other legislative proposals, such as the “Restoring Board Immunity Act” (which piggybacks off the aforementioned case and encourages state licensing reform in exchange for antitrust immunity) should also be considered.

Regardless of the specific proposal, it’s clear that licensing reform is needed, has bipartisan support, and could help many American workers who lost a job due to COVID-19 and are now trying to set out on their own. They admirably adapted in the face of seismic changes to the U.S. economy—changes that could persist long after vaccines have been widely distributed—and many are now thriving in what could very well be the “new normal.” Governments should get out of their (and others’) way.

Chart of the Week

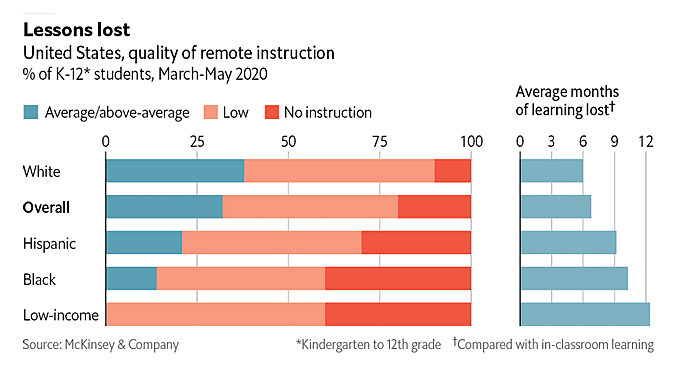

“The repercussions will linger for years.” (source)

The Links

The many U.S. states that supplied your Thanksgiving meal

Non-citizens don’t illegally vote much

Public school enrollment is way down

New research says “savings gluts” don’t cause global imbalances

Trump’s payroll tax executive action is shaping up to be a mess (as expected)