For decades, Latin America has been littered with one currency crisis after another. The best way to avoid these is to dump their disaster‐prone currencies and replace them with the U.S. dollar, as Panama, Ecuador, and El Salvador have done. Dollarization occurs when residents of a country use a foreign currency instead of the country’s domestic currency. The term “dollarization” is used generically and covers all cases in which a foreign currency is used by local residents. Even though other foreign currencies, such as the euro, are sometimes used instead of local currencies, it is the U.S. dollar that dominates; hence, the use of the term dollarization.

There are different varieties of dollarization. Unofficial dollarization occurs when a country issues domestic currency but foreign currencies, or assets denominated in foreign currencies, are also used as a means of payment and/or a store of value. Data on the magnitude of total unofficial dollarization are unavailable. However, estimates of U.S. dollar notes held abroad provide a sense of the magnitude. The U.S. Federal Reserve estimates that as much as 72% of all dollar notes are held abroad. Today, the stock of dollar notes outstanding is $1.99 trillion. So, as much as $1.43 trillion worth of dollar notes are held overseas. And this is just the tip of the iceberg. Indeed, that number only includes U.S. dollar notes held overseas. If we add in all the uses of the U.S. dollar as a unit of account and vehicle currency for the execution of foreign trade and capital transactions, a simple fact emerges: The world is unofficially highly dollarized.

Another class of dollarization is semiofficial. In this case, a monetary system is officially multimonetary. Both domestic and foreign currencies are legal tender. Peru is an example. With semiofficial dollarization, foreign currency bank deposits are often dominant, but a domestic currency is still widely used for transactional purposes and mandated for the payment of taxes.

Semiofficial systems force local central banks to compete with foreign challengers. Consequently, a domestic central bank in such a system should, in principle, be more disciplined than would otherwise be the case. However, the economic performance of unofficially and semiofficially dollarized emerging‐market countries has been highly variable and generally unimpressive.

Who Does It?

Official dollarization occurs when a country does not issue a domestic currency but instead adopts a foreign currency. With official dollarization, a foreign currency has legal tender status. It is used not only for contracts between private parties but also for government accounts and the payment of taxes. Today, the following 37 countries and territories have dollarized systems: American Samoa, Andorra, Bonaire, the British Virgin Islands, the Cocos (Keeling) Islands, the Cook Islands, Northern Cyprus, East Timor, Ecuador, El Salvador, Gaza, Greenland, Guam, Kiribati, Kosovo, Liechtenstein, the Marshall Islands, Micronesia, Montenegro, Monaco, Nauru, Niue, Norfolk Island, the Northern Mariana Islands, Palau, Panama, Pitcairn Island, Puerto Rico, San Marino, Tokelau, the Turks and Caicos Islands, Saba, Sint Eustatius, Tuvalu, the U.S. Virgin Islands, Vatican City, the West Bank. This list does not include monetary unions, like the European Monetary Union, in which member countries all use a “foreign” currency, namely the euro.

The Case of Panama

Panama, which was dollarized in 1903, illustrates the important features of a dollarized economy. Panama is part of the dollar bloc. Consequently, exchange rate risks and the possibility of a currency crisis vis‐à‐vis the U.S. dollar are eliminated. In addition, the possibility of banking crises is largely mitigated because Panama’s banking system is integrated into the international financial system. The nature of Panamanian banks that hold general licenses provides the key to understanding how the system as a whole functions smoothly. When these banks’ portfolios are in equilibrium, they are indifferent at the margin between deploying their liquidity (creating or withdrawing credit) in the domestic market or internationally. As the liquidity (credit‐creating potential) in these banks changes, they evaluate risk‐adjusted rates of return in the domestic and international markets and adjust their portfolios accordingly. Excess liquidity is deployed domestically if domestic risk‐adjusted returns exceed those in the international market and internationally if the international risk‐adjusted returns exceed those in the domestic market. This process is thrown into the reverse when liquidity deficits arise.

The adjustment of banks’ portfolios is the mechanism that allows for a smooth flow of liquidity (and credit) into and out of the banking system (and the economy). In short, excesses or deficits of liquidity in the system are rapidly eliminated because banks are indifferent as to whether they deploy liquidity in the domestic or international markets. Panama can be seen as a small pond connected by its banking system to a huge international ocean of liquidity. Among other things, this renders unnecessary the traditional lender‐of‐last‐resort function performed by central banks. When risk‐adjusted rates of return in Panama exceed those overseas, Panama draws from the international ocean of liquidity, and when the returns overseas exceed those in Panama, Panama adds liquidity (credit) to the ocean abroad. To continue the analogy, Panama’s banking system acts like the Panama Canal to keep the water levels in two bodies of water in equilibrium. Not surprisingly, with this high degree of financial integration, there is virtually no correlation between the level of credit extended to Panamanians and the deposits in Panama. The results of Panama’s dollarized money system and internationally integrated banking system have been excellent when compared with other emerging market countries.

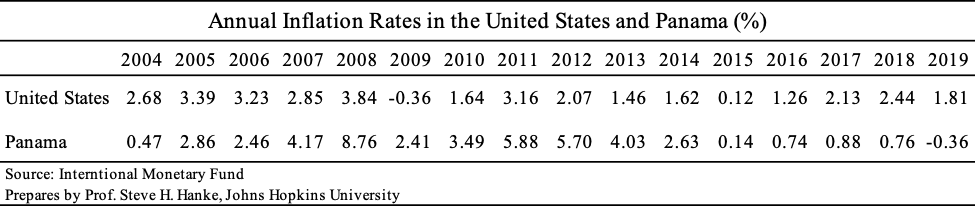

For example, since Panama is part of a unified currency area, its inflation rate mirrors, broadly speaking, the rate of inflation in the United States. Over the past 16 years, inflation in Panama has averaged 2.8% per year; whereas, the U.S. inflation rate has averaged 2.1% per year.

Creating Stable Growth

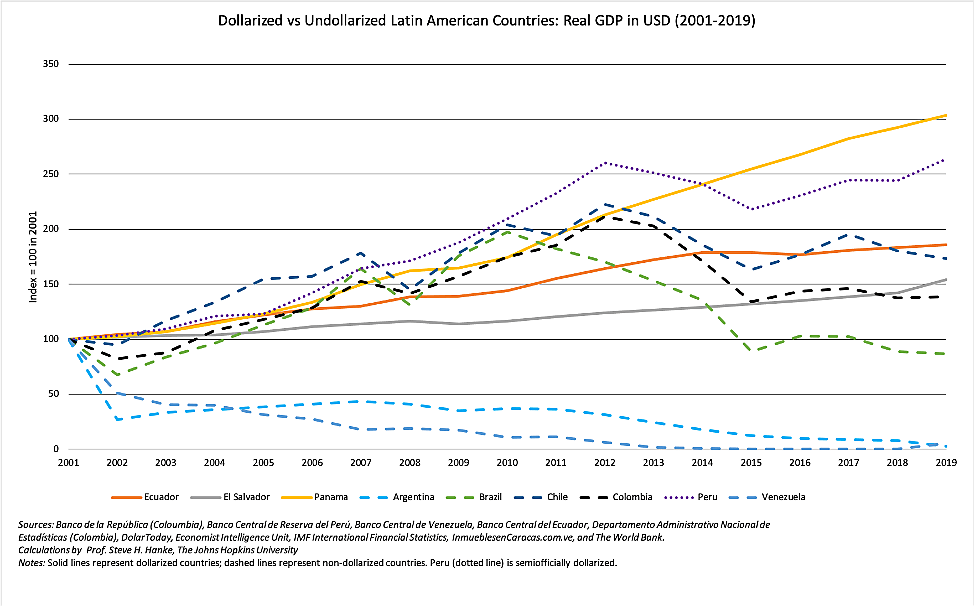

In addition to lower and less variable inflation rates, officially dollarized countries produce higher and more‐stable economic growth rates than comparable countries with central banks that produce domestic currencies. Dollarization is, therefore, desirable. The figure above shows the normalized values of real gross domestic product (GDP) in terms of U.S. dollars between 2001 (index value = 100) and 2019 for nine Latin American countries. Three—Panama, Ecuador, and El Salvador—are officially dollarized, while Peru is semiofficially dollarized. In the three officially dollarized countries, real GDP growth has been more stable and generally superior to growth in the countries that issue their own domestic currencies. While Peru’s growth has only been surpassed by Panama’s, it is less stable than growth in the three officially dollarized countries. The sharp changes in terms of trade, which were associated with the commodity cycle, affected the volatility of real GDP measured in U.S. dollar terms much more in the countries that issued their own domestic currencies than it did in those that were officially dollarized.

Montenegro and Zimbabwe

Whereas Panama has been dollarized for over a century, several non‐Latin American countries have dollarized only recently. One is Montenegro, where I served as a State Counselor and adviser to President Milo Djukanović (1999–2003). In 1999, Montenegro was still part of the rump of Yugoslavia. Montenegrins were fed up with the depreciating Yugoslav dinar and Yugoslavia’s endemic inflation. This should be no surprise. Yugoslavia’s great hyperinflation peaked in January 1994, when the monthly inflation rate was 313 million percent.

Montenegro’s official currency in 1999 was the discredited Yugoslav dinar. But the mighty German mark was the unofficial coin of the realm. Indeed, Montenegro was unofficially dollarized. Montenegro’s president, Milo Djukanović, knew that the German mark was his trump card. If Montenegro officially adopted the mark, it would not only stabilize the economy but also pave the way for reestablishing Montenegro’s sovereignty. On November 2, 1999, he boldly announced that Montenegro would officially adopt the German mark as its national currency. This was Montenegro’s first secession step.

The Montenegrin economy stabilized immediately and began its steady growth amid falling inflation. In May 2006, voters in Montenegro turned out in record numbers to give a collective thumbs‐down to their Republic’s union with Serbia. Montenegro was once again independent. And, on March 15, 2007, Montenegro signed a stabilization and association agreement with the European Union (EU), the first step toward EU membership. Then, on December 17, 2010, Montenegro received word that it was a candidate to join the EU.

Another recent case is that of dollarization that occurred in Zimbabwe. In 2008, Zimbabwe realized the second‐highest hyperinflation in world history with a monthly inflation rate in November of that year at 79,600,000,000% (79.6 billion percent). Faced with that inflation rate and 100‐trillion‐dollar (ZWD) bills, Zimbabweans simply refused to use the Zimbabwe dollar notes. Consequently, Zimbabwe unofficially and spontaneously dollarized. In April 2009, the government was forced to officially dollarize. With that, the “printing presses” were shut down, the government accounts became denominated in U.S. dollars, a new national unity government was installed, and the economy boomed.

That rebound persisted during the term of the national unity government, which lasted until July 2013. During this period, real G.D.P. per capita surged at an average annual rate of 11.2 percent. And, with the imposition of dollarization and the inability for a monetary authority (read: a central bank) to extend credit to Zimbabwe’s fiscal authorities, Zimbabwe’s budget deficits were almost eliminated.

Zimbabwe’s period of stability was short lived, however. With the collapse of the unity government and the return of President Robert Mugabe’s Zimbabwe African National Union – Patriotic Front party in 2013, government spending and public debt surged, resulting in economic instability. To finance its deficits, the government created a “New Zim dollar,” and Zimbabwe de‐dollarized. The New Zim dollar was issued at par to the U.S. dollar, but traded at a significant discount to the U.S. dollar. The money supply exploded in Zimbabwe, and so did the inflation rate. Indeed, on September 14, 2017, Zimbabwe entered its second bout of hyperinflation in less than ten years.

It’s time for Latin America to dump its junk currencies and dollarize.