Has the spread of capitalism been a net positive or a net negative for women around the world? To examine this important and increasingly contested question, Cato hosted a debate in September between Veronique de Rugy, senior fellow at the Mercatus Center at George Mason University, and Nicole Aschoff, author and editorial board member at the socialist magazine Jacobin.

Nicole Aschoff: The question of whether capitalism is good for women is one that both feminists and nonfeminists have debated for a long time, but each upsurge of interest in the question is embedded in a particular context. So what are the conditions of the present moment that encourage an exercise such as this? For one thing, capitalism is in crisis, albeit not necessarily an economic crisis in the sense of a full-blown recession. But we have seen more than a decade of stimulus that includes a multi-trillion-dollar bailout by central banks, years of quantitative easing, and a new normal of government-engineered low interest rates to keep investors from collectively hurling themselves off a cliff.

Nicole Aschoff: The question of whether capitalism is good for women is one that both feminists and nonfeminists have debated for a long time, but each upsurge of interest in the question is embedded in a particular context. So what are the conditions of the present moment that encourage an exercise such as this? For one thing, capitalism is in crisis, albeit not necessarily an economic crisis in the sense of a full-blown recession. But we have seen more than a decade of stimulus that includes a multi-trillion-dollar bailout by central banks, years of quantitative easing, and a new normal of government-engineered low interest rates to keep investors from collectively hurling themselves off a cliff.

Despite these inducements, wages and economic growth are stagnant and companies seem more interested in rolling the dice on the stock market than brick-and-mortar investment. Moreover, neoliberal capitalism — the norms, ideas, and policies that undergird the status quo of the past four decades — is experiencing a deep crisis of legitimacy. There is a widespread loss of trust in government, a waning faith in capitalism, and a resurgence of populism on both the left and the right.

A second point of reference for our discussion here tonight is the resurgence of feminism in the past decade, both in the United States and globally. This resurgence has taken a variety of forms and has encompassed a range of perspectives on how best to pursue a feminist program, but it is a persistent feature of public discourse. Most recently we have seen this in the #MeToo movement.

The idea that feminist goals can be best achieved by each woman striving to reach a position of power and success within capitalism is increasingly in doubt. As we see more and more, women, particularly younger women, are calling for a different kind of feminism that often has strong anti-capitalist themes. Now is the time to both assess hard-won victories and strategize about how to make it possible for all women to actually enjoy them, and to push forward with new concrete demands that fulfill the broad aims of feminism.

So, the first question: Has the spread of capitalism been a net positive or a net negative for women? This is a great question, but it’s also a very difficult question to answer, not least because I find it somewhat odd to formulate an equation of human costs that spans centuries of capitalism. Do more recent improvements in life expectancy, literacy, and women’s autonomy outweigh the mass slaughter of indigenous women and children, the desperate lives of women trapped and tortured in chattel slavery, the disfigurement and early deaths of women who spent their life toiling in sweatshops, their bodies destroyed by factory work? A difficult calculation to be sure. But if we were to attempt it, we would certainly have to temper the sunny claims of global capitalism’s recent successes with the stark reality that more than two billion people suffer globally from malnutrition. At the bottom, 60 percent of people worldwide miss out on 95 percent of new income from global growth, and the absolute number of people living in poverty has risen by a billion people over the past few decades.

I’m willing to say, in agreement with Karl Marx, that capitalism is better than feudalism. We can also point to data that suggest aggregate progress. For example, progress has been made toward the fulfillment of the United Nations Millennium Development Goals on life expectancy, mortality, and education. Middle- and upper-class women in much of the world enjoy access and rights that would have been the envy of their sisters a century and a half ago. But in celebrating these gains, we should be cautious about the causal arrows we draw. Some of these gains can be attributed to development and rationalization, both of which are correlated with capitalism. Many of these gains are the result of political struggle, not capitalism. Laws and norms against discrimination, the right to not be the property of our husbands, the right to vote, to be able to protect ourselves and our children from domestic violence, and so many other rights were not handed down from on high by the chamber of commerce.

These rights were won by social movements, many of which were led by socialists and feminists who fought tooth and nail and suffered many defeats on the way to getting them. In this moment, however, I think it’s important to look forward, as I said earlier. Even if we were to concede that capitalism has been a net gain for women — which I don’t — it is much more important to ask whether capitalism will lead to gains in the future. Feminism is not just about eliminating gender-based discrimination. It’s about fighting for and creating equality and a good life for everyone regardless of their sex, gender, race, ethnicity, education, income, religion and where they live. This is what’s great about feminism. It’s why I’m a feminist. Simply put, we can’t achieve these goals in capitalism. This week is the climate strike, so let’s consider the example of climate change. Nothing demonstrates the failure of the so-called free market better than the looming climate catastrophe.

While capitalism may be rational for individuals, on a systemic level it is highly irrational. The reckless pursuit of profit by individual capitalists who have been empowered by elites and governments has created the massive collective-action problem of global warming. Not to mention resource depletion and habitat destruction. But instead of addressing this problem head on, a problem we understood the rough contours of decades ago, for the past 40 years elites and business owners have insisted on the healing power of free markets.

Historically, sexism and racism have been a core part of strategies of accumulation in capitalism. Sexism makes women’s unpaid labor in the home, which is essential to society and to our economy, appear to be natural. A labor of love. Sexism and racism also continue to be extremely handy tools in the business owner’s toolkit to divide and oppress workers to discourage demands for better pay and benefits and efforts to form unions.

Has capitalism helped to empower women enhancing their material well-being and fostering gender parity? Rather than posing our questions and answers as either/or, we should opt for a more nuanced discussion. As I said earlier, women have been empowered in capitalism. But we should be cautious not to confuse correlation with causation. Keep in mind those lurking variables such as the women’s movement, the civil rights movement, the labor movement, and the environmental movement, but even with those it is still the case that markets can empower women. Money equals power under capitalism, and some women have clearly obtained some of that. Women are lucky enough today to ride on the success of past social movements. So if women are lucky enough to be born to rich parents or be gifted with fantastic abilities or intelligence or any number of other serendipitous happenings that land them in a well-remunerated, fulfilling job, their ability to earn well will empower them. More than that, it will help them empower others in their networks, such as their own children.

But observing that some women are quite empowered in capitalism does not imply that the path has been laid and that if we just follow it, the goals of feminism will be reached. The fabulous wealth of the relative few at the top is not an accident, or a harmless peak over a healthy floor of people living a good life. The “market-friendly” reforms over the past few decades have made a handful of people, mostly men, unimaginably wealthy, while the vast majority of people have seen their livelihoods stagnate, and their opportunities narrow. The incredible technological and scientific advances of the past 40 years could have been channeled toward dramatically reducing poverty and improving healthcare outcomes and the ecological sustainability of our production processes. It could have been channeled toward ensuring security and the supply and distribution of clean water, nutritious food, and adequate housing. These are things that all people value. These are also things that would greatly empower women who suffered disproportionately from the lack of these things. We have the tools to vastly improve the lives of the world’s women, and all people, for that matter.

We haven’t directed our resources, knowledge, or energy toward achieving this goal. Why? Because the goal of capitalism is not a better world. It’s to make a profit.

Veronique de Rugy: Does capitalism help or hurt women? I have to admit that it took me a while to be able to take this question seriously. But then I did a Google search and I saw the amount of writing about how capitalism is oppressive to women, and so I guess this really is a serious issue. It was hard for me, because every aspect of my life I owe to the privilege of living in the closest thing to a capitalist regime. I’m educated, I work, I’m a mom, I was able to choose the country where I live. I can choose my religion, I can choose my political affiliation, I can even choose to be a libertarian, and I can make all these life choices without having to depend permanently on a man and without the judgment of others. I’m just one data point, obviously. One of my life choices is that I’m an economist, so I know that one data point is not going to refute the widespread belief that capitalism hurts women.

Veronique de Rugy: Does capitalism help or hurt women? I have to admit that it took me a while to be able to take this question seriously. But then I did a Google search and I saw the amount of writing about how capitalism is oppressive to women, and so I guess this really is a serious issue. It was hard for me, because every aspect of my life I owe to the privilege of living in the closest thing to a capitalist regime. I’m educated, I work, I’m a mom, I was able to choose the country where I live. I can choose my religion, I can choose my political affiliation, I can even choose to be a libertarian, and I can make all these life choices without having to depend permanently on a man and without the judgment of others. I’m just one data point, obviously. One of my life choices is that I’m an economist, so I know that one data point is not going to refute the widespread belief that capitalism hurts women.

Let’s look at this question and let’s define: What is capitalism? There are many different ways to define capitalism, and I will tell you what it means to me. First, capitalism is an economic system. So if you want to actually judge it, you need to look at its economic performance. In its ideal form, capitalism requires a small government. Capitalism rests on individual freedom and voluntary consent. That means that you can’t force people to do what they don’t want to do, the same way they can’t force you to do their bidding. But also, in an ideal capitalist system, you can decide who you want to marry, how you want to raise your children, and how to manage your reproductive choices without having to ask the government for permission.

Capitalism requires cooperation, not just competition. This is something that F. A. Hayek highlights a lot in his work. Capitalism is good precisely because it lets individuals express themselves creatively and productively through their work and voluntary community. Now, we must ask ourselves whether this is just an ideal, because maybe in practice capitalism is really awful and oppressive. So, let’s look at the countries that are the most capitalist, as I just defined them, the countries where the government interferes the least in economic affairs. By most rankings, the two most capitalist countries are Hong Kong and Singapore. But among the large group of most-capitalist countries, you find countries like the United States and Canada. By historic standards, and even by current world standards, these countries are nice, and they’re rich, and they have relatively low poverty. And this is the reason why so many poor people around the world want to move here, even if it means hard work and low-paid jobs.

But maybe capitalism is good for our country as a whole, but not so good for women. So let’s look at that question. Historically, we can show that capitalism has helped women a fair amount. That’s because free markets have done much more than any other institution to empower individuals and produce an abundance of new and amazing goods and incredible technological innovation for the benefit of all. I cannot overstate the fact that we are all the beneficiaries of the gift of innovation. Nobel Prize laureate William Nordhaus’s work shows that when you take the top innovators in the United States in the second half of the 20th century, they only captured 2 percent of the social value that they created with their innovations. They were forced to share 98 percent of the gains through competition and lower prices with us consumers. That’s a big deal, and it has been a big deal historically for women. Innovations such as urban sanitation, clean running water, and modern medicines have actually increased the quality of women’s lives immensely. But then the next question is: Women may live longer and in better health, but what has capitalism done to emancipate them? Three key things in my opinion.

First, innovation doesn’t just save lives, it reduces the time burden on women, and that has historically allowed more of them to enter the labor force. Just to give you an example, in 1910 the amount of time women spent daily preparing food was six hours, on average, and today it is an average of just one hour. And that holds true across income levels. What this has done is bring to low-income people a lot of goods and opportunities that used to be only accessible to rich people.

The second thing innovation does is create income, and increases in income have always preceded higher levels of education for women. When resources are scarce, families historically tended to invest in their sons because it seemed like a better investment. When income rose, then they could invest in both. They didn’t have to choose. That was extremely empowering for women.

The third thing that capitalism has done for women is increase not only income, but also the demand for labor. When you think about the fact that innovations have reduced the necessity of physical strength to do remunerative work, that means lot of new work options became more available to women. The increase for them was, in fact, many times the increase that we’ve seen for men. And as soon as women started to be able to secure independent incomes and support themselves, it meant that not being married was not an utter catastrophe like it used to be. And it is still the case for a lot of women today. All these factors explain why, as historian Stephen Davies has noted, the early pioneers of feminism were ardent classical liberals and supporters of capitalist industry. Feminists were not always anti-capitalist, and those women were right to put their faith in freedom and capitalism.

We have plenty to do, of course. I do not just defend the status quo on these issues. Occupational licensing laws, criminal justice reform, and many other topics that the scholars here at Cato work on every day are an important part of the work still to be done. But all in all, capitalism realistically beats all existing alternatives. Unfortunately, it seems to me people take for granted the bounty created by capitalism. This is why our challenge, for all of us, is to constantly make capitalism and freedom an exciting undertaking for the next generation. Women have much to gain from building a freer society.

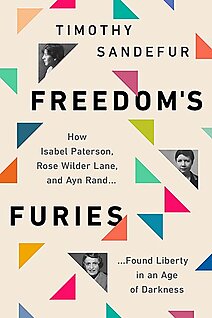

Featured Book

Freedom’s Furies

In 1943, three books appeared that changed American politics forever: Isabel Paterson’s The God of the Machine, Rose Wilder Lane’s The Discovery of Freedom, and Ayn Rand’s The Fountainhead. Together, they laid the groundwork for what became the modern libertarian movement.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.