Other economic fundamentals suggest low fiscal multipliers right now as well. U.S. federal public debt stands at over 77 percent of GDP. The long-term outlook for the public finances is dire, driven by rising entitlement spending reflective of demographic trends and rising health care costs. The federal deficit is projected to be 2.9 percent in 2017, but if current policies remain largely unchanged, the CBO estimates that the annual deficit would rise to 4 percent of GDP over the next decade. That estimate is largely due to a continued growth in spending on Social Security and Medicare. Even this scenario would envisage taxes rising 1 percentage point above the average of the past five decades.

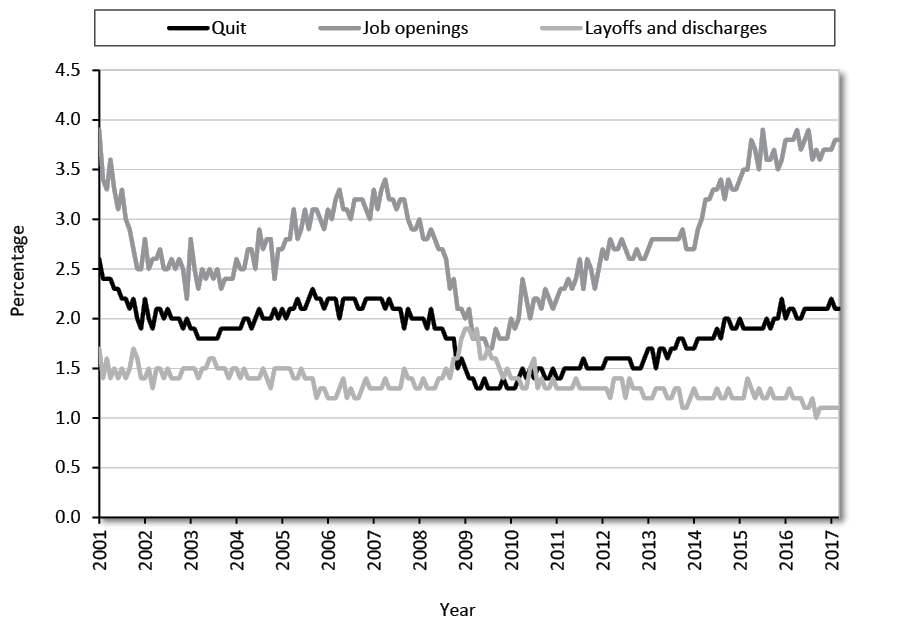

Figure 3

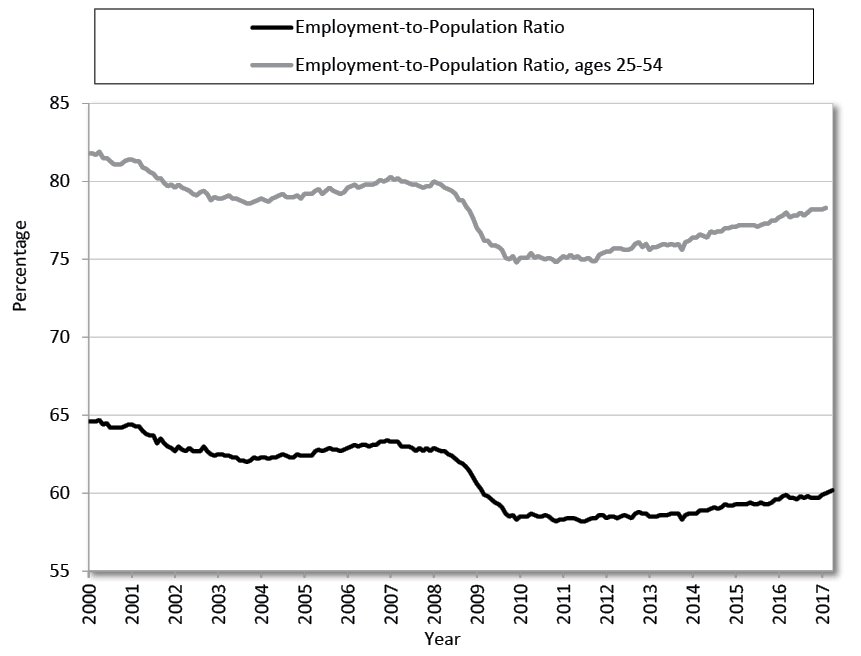

Civilian Employment-to-Population Ratio and Employment-to-Population Ratio for 25- to 54-Year-Olds

Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Employment Situation.

Against such a backdrop, a period of sustained growth would seem an appropriate time to consolidate the public finances through spending restraint and long-term entitlement reform. Theory would also suggest that any stimulus would be less powerful, as consumers and investors are increasingly aware of possible future tax increases. It would not seem the time to raise discretionary borrowing through an infrastructure stimulus program.

As a result, fewer economists nowadays argue that fiscal stimulus is necessary or desirable. Ben Bernanke, former chair of the Federal Reserve, exemplified this shift when he wrote, “Today, with the economy approaching full employment, the need for demand-side stimulus, while perhaps not entirely gone, is surely much less than it was three or four years ago.”46

Nevertheless, some economists continue to justify increases in spending. Krugman has previously suggested infrastructure investment as stimulus would be an “insurance,” given the U.S. economy remains close to having interest rates at zero.47 In his view, a possible downturn could lead to a position where once more the central bank has to slash interest rates. More government investment today could therefore help lift the natural rate of interest, giving more room for the Fed to cut interest rates in the future should a downturn appear.

Yet this argument only goes to show that infrastructure investment, as a “fiscal stimulus,” will not boost GDP. Any economic boost brought about by the higher investment spending would be offset by the Fed raising interest rates.

Krugman gets around this by implying that the Fed has raised interest rates prematurely, meaning they may currently be above their natural rate, dragging the economy below its full employment potential. For fiscal stimulus to raise GDP, the Fed would then have to about-turn on its view that interest rates should be raised and to decide not to offset any fiscal stimulus with monetary tightening. Krugman would have to be right and the Fed wrong about the economy having plenty of spare capacity, and the infrastructure investment would have to be delivered promptly. For the reasons outlined, these conditions seem unlikely. The cyclical position and structural state of the U.S. economy suggest that a federal investment–led fiscal stimulus neither is necessary nor would be effective.

A separate case says significant public infrastructure investment is necessary to enhance productivity. According to this view, the United States has an “infrastructure deficit”—a need for maintenance or new infrastructure—given current demands or projections of future economic activity. Absent this investment, potential growth will be diminished.

The growth performance of the economy has been sluggish compared with past recoveries, and the Federal Reserve believes the long-term sustainable annual growth rate of the economy is now a mere 1.8 percent. The sustained downturn in productivity even as unemployment has fallen suggests a problem on the supply side of the economy, perhaps because the conditions for growth are getting harder or bad policies are producing a strong headwind against robust productivity growth.

In such an environment and with interest rates still low, so the argument goes, this is an opportune time for the government to invest in roads, rail, energy, housing, and ports that will facilitate robust productivity growth in future.

Few economists would argue that better infrastructure would not, all else equal, enhance a country’s economic potential.

Consider a new highway that reduces the connection time between two cities. A reduction in travel times lowers costs for businesses requiring the movement of inputs and labor through production and delivery. Lower costs boost a company’s profits and increase its use of roads between the routes, because of the effective fall in the price of transportation. Provided markets are contestable and competitive, in time profit opportunities induce companies and individuals to relocate to the area now connected through improved transport links. The ultimate beneficiaries are customers who enjoy lower prices on final goods.

Some of the new activity will simply be displacement from other regions. But overall economic activity will have increased as a result of better connectivity. Productive infrastructure reduces costs and expands markets, allowing better realization of factor specialization and agglomeration effects. The inverse applies too. Worsening connections caused by disrepair or outmoded facilities raise input prices and reduce the beneficial effects of specialization.

Of course, infrastructure investment uses scarce resources. To assess whether a particular investment has truly raised productivity, it must be judged against alternative uses of the funds. The extent to which improved infrastructure actually feeds through into productivity improvements also depends on how much the lowered costs compare with the total cost of production. That is why all individual proposals should be judged on their own merits. But what is clear is that a strong theoretical basis exists for believing that good infrastructure improves productivity.

What is the best means of achieving infrastructure investments to enhance productivity and long-run growth? Do we need public investment and planning through government, or are free markets capable of enhancing supply as demands change?

The justifications for government provision or oversight of infrastructure projects can be split into three broad categories: (a) markets fail and require government correction; (b) the cost of government borrowing is cheap, and it is economical for governments to invest; and (c) governments can put social ambitions above narrow commercial interests. The following sections evaluate each of those justifications.

Market failure. Transport and water infrastructure are said to share some of the features of “public goods,” meaning they might be unprovided or underprovided in a free market. The Brookings Institution gives the example of a levee. Once built, a levee provides flood protection for an entire town or village. Because nobody can be effectively excluded from its benefits, voluntary payments would unlikely occur for the levee before development. Individuals would have an incentive to free-ride on the generosity of others.48 In the absence of government provision, the levee would not be built.

In other words, government involvement in infrastructure provision can theoretically help solve a collective action problem to improve social welfare. Taking road construction as an example, the government may be better placed than private actors to deal with the transaction costs associated with construction spanning the property of different landowners.49 In other cases, socially beneficial investment might take place only alongside government privileges, such as noncompete clauses or agreements inserted into contracts for toll road development to allow investors relative certainty on returns by restricting the development of competing roads nearby.

Many (particularly large) projects certainly have significant external effects too, whether environmental spillovers, noise pollution, or displacement to surrounding areas. When assigning clear property rights and compensation is not possible, it is believed that government can intervene to ensure that these social costs and social benefits are considered.

Yet historical examples of private-sector delivery suggest that the “market failure” arguments for public investment are weaker than often asserted. Virtually the entire rail network in the United Kingdom (UK) was privately built and operated for more than 100 years before its nationalization following World War II. In the United States, the pioneering Philadelphia and Lancaster Turnpike Corporation began building private turnpikes in the late 18th century, and for the first third of the 19th century, private companies built thousands of miles of road.

The private sector can and does build roads and railways now. Road owners can and do charge tolls for use when they can, whereas railway owners can buy up the land around their tracks and thus capitalize on the appreciation in land values following the development of a rail line. In many other countries, airports and associated infrastructure are privately owned and delivered, with the government’s role often limited to applying a framework to deal with land-use planning, spillover issues, or complementary infrastructure in the surrounding area. Investors in London’s Heathrow Airport, for example, recently agreed to a plan to deliver £650 million ($810 billion) in additional investment in 2019.50 The biggest barriers to private investment in major projects are often regulatory or related to uncertainty (discussed later).

Correcting for “market failures” also tends to be a lot more difficult in practice than in theory. Most activities have external effects that are highly uncertain. The mere presence of externalities is not a sufficient condition to justify government action. It may be that private returns are still high enough that a project would be undertaken anyway, even though it has additional social benefits. With scarce resources, it is also necessary to review not just whether a project has some social benefits, but also whether the social rate of return is high compared with other uses of funds.51 There is even some evidence that some things traditionally thought to be public goods, such as lighthouses, actually get produced in a market economy.52

We should be skeptical then of those who use “market failures” as a justification for widespread government provision of infrastructure. That is not to say that some worthy projects would not be produced in a market economy. Government should undertake certain infrastructure projects if they are strongly socially desirable but not privately profitable. But that is likely to occur much less frequently than commonly believed. What is more, most projects with significant spillover effects tend to require highly localized knowledge, meaning state or local government would be better placed than the federal government to undertake any investment.

Cheap government borrowing. A less convincing argument says government should undertake large-scale investment because government borrowing is cheap. With real interest rates very low in 2015, Nobel laureate Robert Shiller argued, “The government should be borrowing, it would seem, heavily and investing in anything that yields a positive return.”53

The Brookings Institution recently employed similar logic, suggesting low rates should also be inducing private-sector investment.54 Many are puzzled by the private sector’s not taking advantage of this “near-free” money to invest in anything with a positive return. Surely, in this environment, they say, it makes sense for government to “step up.”

The mistake here is to conflate a less costly time to invest with a “good time” to invest. Take the example of a toll road. If the long-term outlook indicates the growth or the population of an area will slow, then expected use of the toll road would fall, as would demand for investment. That result would lower equilibrium interest rates. Even if the interest rates are lower, it would not be a good time to invest because demand for the toll road would be falling, lowering revenue expectations.

Similar logic applies to government investment in transport infrastructure without user fees. If demand for transportation use is falling for structural reasons, then any investment will have far fewer economic benefits, even if costs have fallen. The overall attractiveness of the project might be unchanged or may have deteriorated. Examining what has happened to interest rates alone tells us little about whether undertaking a project is worthwhile.

The fact that private-sector companies are not investing massively at low rates in infrastructure projects suggests that it may simply not be a good time to invest generally. The explanation might be because expected returns are poor. But it also might be because uncertainty is high.

Infrastructure investment comes with significant political risk. In France, the government declared it would limit increases in tolls on roads, despite contractual agreements with operating companies allowing increases via inflation-linked formulas.55 In Spain, a British investment fund took legal action against the government after it attempted to lower airport tariffs, despite a guarantee that they would be fixed for 10 years after privatization. The Norwegian government likewise stands accused of changing the regulatory framework surrounding oil pipelines after investments were made.56 Political risks of this kind are amplified when projects have exceptionally long lead times, with environmental and other policy decisions potentially being altered midproject.

Political risk comes on top of risks associated with construction costs and usage, some of which might be correlated with general economic health. There will be uncertainties unrelated to GDP too. The success or otherwise of high-speed rail and much mass transit, for example, is strongly linked to the potential for technological change, not least driverless cars. Private investors may fear the whole venture will become obsolete.

That the private sector fails to invest in such projects does not show “market failures” in many instances. It merely shows that private investors consider the project too risky or uneconomic. This is something politicians should bear in mind when committing taxpayer funds.

Low interest rates do reduce the fiscal cost of borrowing, but one must also consider the revenue/growth component and its effect on returns. All infrastructure investments should still go through rigorous cost–benefit analyses and be judged against alternative uses of the funds, including the option of leaving the money in the hands of taxpayers.

Social, rather than commercial, AIMS. Private companies will invest in projects in which they can make a profit. Governments can invest to achieve other social objectives. That argument is often heard for government-led investment. Of course, in many cases, that is at odds with the claim that government will invest prudently to raise productivity, although in some cases—such as those in which environmental projects help correct externalities—the two need not be incompatible. Nevertheless, resources for infrastructure allocated through the political process clearly seek other objectives, often with economic costs.

Short-term job creation is often one declared objective. Trump’s team has promised to prioritize schemes that directly create jobs. Yet, as noted previously, jobs are a cost to projects. If “job creation” is a target of government investment, then projects may be chosen and delivered in a less efficient manner than they could be, raising the burden on taxpayers through making infrastructure delivery more expensive.

Regional favoritism and pork-barrel spending often occur too. Infamously, in July 2005, Congress passed a bill that included earmarked funds for the Gravina Bridge in Alaska, the so-called Bridge to Nowhere. It was not funded with a view toward maximizing returns or allocating funds according to market demands. It is well known that Amtrak has historically allocated resources for investment to rural areas with low population densities at the behest of politicians.57 The Highway Trust Fund also allocates funds seemingly divorced from needs. A 2013 paper found that states with greater highway use or a larger highway system did relatively badly with regard to federal aid.58 The CBO echoes this criticism, noting that “spending on highways does not correspond very well with how the roads are used and valued.”59

For political gain, politicians also grant funds to prestige or so-called ribbon-cutting projects, rather than to projects with the highest economic returns, such as maintenance, repair, and bottlenecks. Consider that federal funds have been granted to the California High-Speed Rail scheme, which originally had a purported benefit–cost ratio of about 2.60 The estimated costs for this project have since expanded rapidly and are still rising, taking the estimated benefit–cost ratio closer to 1 already.61 Meanwhile, other schemes with much higher benefit–cost ratios have not received funds. The outgoing Obama administration highlighted the $8 billion Hampton Roads highway project, for example, that had a benefit–cost ratio of about 4.62

Choosing to prioritize investments that do not have the highest returns is a phenomenon not unique to the United States. In the United Kingdom, the coalition government’s 2010 Comprehensive Spending Review (which aimed to reduce government expenditure in light of a huge budget deficit) led to deferral, cancellation, or review of a host of road schemes with average benefit–cost ratios of 6.8, 3.2, and 4.2, respectively. Yet the government pushed on with plans for a high-speed rail project between London and Birmingham despite the high-speed line’s purported benefit–cost ratio of just 1.2.63 New historical evidence suggests a potential rationale: grand infrastructure projects can help boost electoral performance.64

Quirks in funding allocation also mean that on occasion politicians threaten the withdrawal of resources for infrastructure to achieve political objectives. Recent news reports suggest President Trump may cut transportation funding as a means of punishing so-called sanctuary cities.65 Allocating funds according to a city’s application of immigration laws—disregarding the congestion or other needs of the locality—is clearly not economically optimal.

That government investments are not bound by market discipline and often become politicized with other objectives is the reason projects are often not delivered efficiently.

The book Megaprojects and Risk: An Anatomy of Ambition—written by Oxford University economic geographer Bent Flyvbjerg and others—goes into detail about some of the accountability problems associated with political management.66 The conflicted role of both promoting a project and being responsible for examining its failures and risks leads politicians to make overoptimistic claims about a scheme’s benefits relative to costs. Politicians’ desire to leave an infrastructure legacy (with costs realized long after they have left office) means most large projects are mis-sold to electors. That factor manifests itself in a lack of realism about initial costs, underestimating the time a project will take, setting contingencies too low, not taking into account changes in specification, overestimating usage, and not accounting for some of the nonmonetary spillover effects of the project itself (congestion brought about by construction activity, for example).

Flyvbjerg and others highlight how a 1998 study by the U.S. Department of Transportation found that 10 U.S. rail transit projects with a total value of $15.5 billion saw a total capital cost overrun of 61 percent.67 Their finding corroborates a large study of 258 projects across 20 countries undertaken at Denmark’s Aalborg University that found 9 out of 10 such projects end with cost overruns, with rail projects costing 45 percent more than expected on average; tunnels and bridges, 34 percent; and roads, 20 percent.68 Urban rail projects seem to be particularly prone to higher-than-expected costs and lower-than-expected revenues. This systematic bias in one direction suggests we cannot attribute such overruns to mere error.

Recognizing some of these failings in delivering infrastructure efficiently, governments have sought in recent decades to harness private-sector capital to infrastructure provision, mainly through public-private partnerships (PPPs).

PPPs entail agreements between government and a private contractor for the building, financing, or operation of government infrastructure projects with the aim of passing on substantial risk to the private sector. According to the U.S. Department of Transportation website, PPPs can take five distinct forms for new infrastructure, ranging from simply transferring management responsibilities to a private-sector firm to integrated contracts incorporating the design, build, maintenance, and operation of the infrastructure (for example, toll roads). The idea is PPPs can provide the infrastructure government desires, harnessing commercial discipline in the delivery and maintenance of projects as agreed in a contract with government.

In sum, government may have a role in the provision of genuine public goods and in projects in which the social rate of return is very high and the project would not be delivered by the private sector. A government role in projects is, in many cases, inevitable and in some cases desirable. In principle, well-targeted state-financed infrastructure undertaken according to disciplined cost–benefit analysis buttressed with systematic risk evaluation can enhance economic welfare.

But these assumptions speak for themselves. Historical examples suggest that the market failure arguments for infrastructure development may be overblown. Governments can often borrow cheaply, but that tells us little about overall project desirability. Certainly, governments often pursue objectives other than economic growth, and the political process does not lend itself well to effective targeting and monitoring for investment. PPPs can help on particular projects, but even here many of the problems associated with government remain (as we will explore). A role exists for certain government investments, but the U.S. federal government already seems to be beyond that limited role.

Unsurprisingly, given all these caveats and conditions, the evidence on the relationship between government infrastructure investment and growth is extremely mixed. It stems from three types of analysis: (a) cross-country regressions, (b) individual country case studies, and (c) time series work on the United States.

Using large panel data sets across countries, the most up-to-date evidence for advanced economies suggests small but significant positive effects of government investment on productivity growth, with a 10 percent increase in infrastructure assets raising GDP by 0.7 percent.69 These approaches, which regress growth on public investment, are believed by many to be the best means of measuring the true effect of investment, because they capture all potential spillovers to the broader economy.

Even here, estimates have considerable differences, depending on the countries, time periods, or types of investments examined. As an example, a 2014 study by Andrew Warner for the IMF focusing on 126 low- to middle-income economies (where one might have thought infrastructure investment more essential) found, for example, “no robust evidence that the investment booms exerted a long-term positive impact on the level of GDP.”70 Although a case for eliminating transport bottlenecks exists, the study found in its examination of case studies “no evidence that rational selection of public investments according to sound economic criteria was ever seriously followed.”71

There is also a range of methodological difficulties associated with cross-sectional regressions, not least because of the potential two-way relationship between growth and investment and important omitted variables (such as the tax increases needed to finance the investment in some cases).

Individual country-specific case studies show more clearly that substantial infrastructure investment is neither a necessary nor sufficient condition for robust growth. Japan’s huge outlays (according to an article in the New York Times, the country spent $6.3 trillion on “construction-related public investment” between 1991 and 2008)72 produced, among other things, the world’s best-rated rail system.73 Yet productivity increased three and a half times more between 1970 and 1990 than between 1991 and 2011.74

Spain, likewise, was left with empty airports following its infrastructure drive. A recent assessment of a host of major projects in China also showed that a great deal of infrastructure investment was plagued by cost overruns and overestimated benefits, with 55 percent of the projects having a benefit-to-cost ratio below 1. That is, they led to a net loss in economic value.75

Given that the United States has different institutions and policy frameworks than other countries, one has to be careful in generalizing conclusions from elsewhere. Instead, policymakers point to America’s own historical record.

Three decades ago, the scholarly consensus was that U.S. spending on infrastructure yields great public benefits. The work of Bates College economist David Aschauer in the late 1980s purported to show huge returns on public capital using time series data and hence attributed a large portion of the productivity growth slowdown following the postwar boom to a decline in public investment spending.76 Similarly positive results were found by Federal Reserve Bank of Boston (and later Boston College) economist Alicia Munnell.77 This quarter-century-old work still dominates publications seeking increases in infrastructure spending today.

But these studies are believed to have a range of important methodological problems. Edward Gramlich showed convincingly that Aschauer’s estimates were too high to be plausible.78 More recent analysis suggests much more modest effects of public investment on postwar growth rates.79

Historic work, as with evidence from other countries, can get us only so far with regard to lessons for future policy. That public capital investment historically increased growth tells us nothing of the desirability or growth effects of new projects, which should be judged on their own merits. That should be obvious on a conceptual level. The fact that some bridges in the past have enhanced growth tells us nothing of the desirability of a new bridge today.

Take the interstate highway system as a specific example. John Fernald’s work found that its construction substantially boosted productivity in industries closely associated with road use, bringing with it a one-time boost to U.S. economic growth.80 Yet more recent assessments have found that too many new highways were built between 1983 and 2003 and that marginal extensions to the highway system tend not to increase social welfare. The reason is the cost savings of reducing travel times are small relative to incomes and prices.81 That is one reason that meta-analysis suggests that the productivity gains from public capital investment have fallen over time.82

That is not to say that in areas with genuine bottlenecks, where heavy congestion has deleterious effects on labor markets, new investments do not make sense. The key lesson is that we cannot make generalized claims about the benefits of “infrastructure investment” without judging the worthiness of individual projects. Evidence from cross-country regressions and historical data may be interesting in their own right, but they do little to inform us about whether new projects will be beneficial.

White House Press Secretary Sean Spicer recently explained how the Oroville Dam emergency was a “textbook example” of the consequences of the nation’s aging infrastructure. “Dams, bridges, roads, and all ports around the country have fallen into disrepair,” he said. “In order to prevent the next disaster we will pursue the president’s vision for an overhaul of our nation’s crumbling infrastructure.”83

The true state of American infrastructure is better than Spicer suggested. But even if the claims of widespread disrepair were true, would full repair and upgrades of existing infrastructure be a good proxy for how much government infrastructure investment is needed?

Absent real markets, how much infrastructure is wanted or needed is difficult to quantify. What level of congestion would drivers on a particular road be able to tolerate before they were willing to finance road expansion? Clearly, eliminating all congestion with 15-lane freeways would be prohibitively expensive. So how far should a road expansion go? How often should it be repaired? How much transportation should be by train? How much money should be spent on research and development for completely new ways of meeting transportation demand?

Markets are good at finding the optimal mix of infrastructure spending over time and rewarding those that are better at satisfying demand. Governments, even with the best of intentions, lack the necessary knowledge to find that mix. Without effective pricing in most cases for infrastructure, the government is simply unable to judge when new investments make economic sense.

In markets, investments are made when they are believed to be profitable. For government projects, cost–benefit analysis of new projects can be undertaken to decide where scarce resources are most needed for highest returns. But even with this framework, it is impossible to perceive whether enlightened transport technocrats will be able to perfectly estimate the balance of benefits and costs of any new development. We have already seen the overoptimism bias for big projects and the prospect that politicians may prioritize projects with lower returns for political reasons. Even assuming benefits and costs can be estimated accurately, that does not tell us anything about “how much” should be invested in infrastructure projects overall.

In the absence of guidance on this issue, different proxies for how much “should” be invested are quoted in public debate. Most commonly cited are surveys by the American Society of Civil Engineers, which believes the United States needs to invest $4.6 trillion in infrastructure between now and 2025. Its work assesses the condition of infrastructure, estimating how much it would cost to improve the infrastructure to a set standard as measured by eight different criteria: (a) capacity, (b) condition, (c) funding, (d) future need, (e) operation and maintenance, (f) public safety, (g) resilience, and (h) innovation.84

Yet although all those variables have merit, combining them in this way to get an aggregate figure of cost tells us little about what we “should” invest if one considered pure market demands. A cynic might point out that engineers have an incentive to exaggerate the amount of investment that is desirable. Indeed, investigations by CNN found the group’s estimates for infrastructure spending needs were much higher than the sum of those outlined by federal agencies.85

The quality of U.S. infrastructure actually appears relatively high when compared with other developed nations. The World Economic Forum’s Global Competitiveness Report ranks the United States 11th in the world for infrastructure overall, placing it ahead of many advanced economies, such as Australia, Belgium, Canada, and all of Scandinavia. Subindexes rank the United States 12th for roads, 13th for railroads, 10th for ports, and 9th for air transportation. The United States’ overall infrastructure position would be higher still were it not for relatively low numbers of mobile-cellular telephone subscriptions and landlines per capita, where America ranks 66th and 25th, respectively.86

Most of the variables used to construct these indexes are survey based, bringing the disadvantage of varying expectations across countries. The Kiel Institute’s more objective measures of capacity relative to the size of the country put the United States as high as fourth in the world overall and third for transportation infrastructure, behind only the city-states of Hong Kong and Singapore, which clearly have very different characteristics.87

Further, the U.S. government is not currently spending less on investment than other countries. Gross government fixed capital formation in the United States is projected to be 2.9 percent in 2017, above the average of 2.6 percent for members of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. That number is lower than the U.S. average of 4.1 percent since 1960, certainly, but according to the CBO, spending on transportation, drinking water, and wastewater infrastructure amounted to 2.4 percent of GDP in 2014—a figure that has remained fairly stable for the past 30 years.88

Of course, these capacity and spending measures tell us little about the quality of infrastructure, or about the needs of a major economy that is on the international technological frontier. Politicians usually focus on these metrics in making the case for new investments.

Politicians continuously talk of creaking and crumbling roads, highways, and bridges in particular. Democratic presidential candidate Hillary Clinton went as far as to say, “We have bridges that are right now too dangerous to drive on, although people take a deep breath and drive across them.”89 The picture painted is one of U.S. infrastructure falling into dire disrepair.

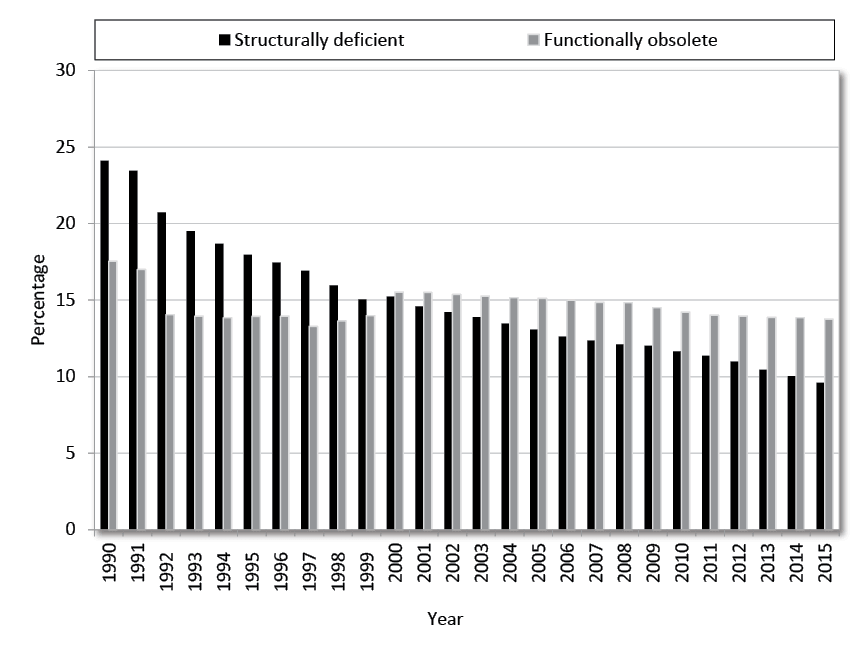

The actual evidence is mixed. It is regularly reported that 58,791 U.S. bridges are “structurally deficient,” and 84,124 are “functionally obsolete,” for example.90 That is as high as 9.6 percent and 13.7 percent of the total 611,845 U.S. bridges, respectively. With such scary-sounding terms and several instances of bridges actually collapsing, no wonder politicians and the public are spooked.

Rarely highlighted, though, are the definitions of these terms and the trends. “Functionally obsolete” does not mean unsafe but refers to the geometrics of the bridge relative to the

Figure 4

Proportion of Bridges Qualifying as Structurally Deficient or Functionally Obsolete

Source: U.S. Department of Transportation, Federal Highway Administration, Office of Bridge Technology, National Bridge Inventory, Count of Bridges by Highway System.

geometrics of modern design standards. As such, older bridges are more likely to be declared “functionally obsolete” simply by virtue of when they were built. Likewise, “the classification of a bridge as structurally deficient does not mean that it is likely to collapse or that it is unsafe,” explains the Federal Highway Administration. “Bridges are considered structurally deficient if significant load-carrying elements are in poor condition due to deterioration or damage.”91

The really important fact is, bridge quality has actually improved substantially since 1990. The proportion of bridges qualifying as structurally deficient and functionally obsolete was as high as 24.1 percent and 17.5 percent, respectively, back then, and the proportion of bridges believed to be structurally deficient has seen nearly annual improvement ever since. That holds for both urban and rural bridges. (See Figure 4.)

Concern about physical conditions may stem from individual catastrophic events, such as the I-35W Mississippi River bridge collapse in Minneapolis in 2007. But those are rarities and tell us little about the consequences of the bridge statistics outlined above. In 2007, when the I-35W bridge collapsed, it was labeled as structurally deficient, for example, but so were 74,055 bridges that did not collapse. In fact, the bridge had been so labeled for the previous 17 years. Inspections have since shown that the bridge’s design was flawed from the start.

Many other measures of quality tell a similar story of improvement. Since 1986, airport runway pavement conditions have improved significantly, with the proportion of pavements registered as good rising from 63.5 percent to 80.5 percent in 2016.92 The Federal Highway Administration estimates that the miles traveled on the National Highway System of “good” ride quality increased from 48 percent in 2000 to 60 percent in 2010, and miles traveled under “acceptable” ride quality increased from 91 percent to 93 percent.93 These improvements continued between 2010 and 2012.94

Figure 5

Annual Person-Hours of Highway Traffic Delay Per Auto Commuter

Source: Texas Transportation Institute, Congestion Data for Your City.

That is not to downplay problems. So-called collector roads—those capacity roads that tend to provide access to residential property—have seen a decline in the proportion regarded as “good quality” in both urban and rural areas. Roadway congestion has also become more acute over the long term. A substantial increase has occurred in the annual person-hours of highway traffic delay per auto commuter across all types of areas, although it has not really increased in recent years (see Figure 5). Similar stories are observed in delays to journeys in peak time against free-flowing traffic and in road congestion indexes.

Rail and transit systems appear to be the main areas with observable deterioration. The proportion of rail transit stations believed to be in excellent or good condition fell from 61 percent in 1995 to 24.9 percent by 2006, with a significant increase in the proportion regarded as substandard.95 The average age of all types of urban transit rail vehicles has also increased since 1990,96 whereas the proportion of urban bus facilities rated substandard or poor rose from 23.7 percent to 36.3 percent between 1997 and 2006.97

Yet although older vehicles and facilities may contribute to the feeling of creaking infrastructure, replacing them may not lead to greatly improved service. It may even be that in some cases neglect is deliberate and reflective of falling demand for the service.

Rather than highlight the scale of investment required, the evidence shown actually says more about who pays for infrastructure and the incentives it creates. As the Cato Institute’s Randal O’Toole has noted, “The difference between state highways, which are in good condition, local roads, which are in fair condition, and transit systems, which are in poor condition, is simple: State road maintenance is paid for almost entirely out of user fees; local road maintenance is paid for by a combination of taxes and user fees; while transit maintenance is paid for entirely out of taxes.”98

The incentive to keep transport networks well maintained is stronger when the operator has a stake in the future revenues associated with the asset. That suggests that policymakers’ focus on creating public revenue streams for infrastructure misses the point. A more fruitful policy agenda would be to shift toward revenue streams from tolling and user fees and to move away from government taxes and spending.

Indeed, it is difficult not to conclude from the overall available evidence that tales of a transportation “infrastructure crisis” are exaggerated, and the case for significant investment on “disrepair” grounds is not clear-cut. Most of the aggregate indicators cited in public debate purportedly showing how much “should” be invested are arbitrary and do not have an economic rationale. To get infrastructure provision that is responsive to people’s wants and needs, we need more in the way of market signals.

Changing patterns of demand and acute points of congestion require investment in maintenance and expansion. The real aim should be to have an institutional framework in which investment is responsive to economic wants and needs. When social returns are high and the private sector will not invest, then government can improve prospects. But more scope for private-sector delivery of infrastructure in the United States clearly exists.

Nevertheless, most debate on infrastructure policy starts with the premise that more infrastructure investment is necessary and then asks where the funds will come from to finance it. Having argued against significant new federal spending, this study uses the following sections to draw on the lessons noted to discuss the mooted proposals to use infrastructure tax credits and PPPs to raise funds. It concludes by highlighting a range of policies the Trump administration should consider to improve the framework for infrastructure decisionmaking and delivery without increasing the burden on taxpayers.

President Trump and his transportation secretary, Elaine Chao, have said the promised $1 trillion investment will include both public and private funds.99 With House and Senate Republicans believed to be reluctant to commit to substantial new federal deficit financing, however, Peter Navarro and Wilbur Ross—as part of President Trump’s campaign team—previously drew up an alternative financing plan that uses tax credits to incentivize $1 trillion of purely private investment. As far as can be ascertained, tax credits of this nature are still being considered today.

The Ross-Navarro plan would entail extremely generous 82 percent tax credits for equity investment into designated projects. The pair envisage that drawing in a total of $167 billion of private-sector equity investment (at a “cost” of $137 billion to the tax base) would then allow private investors to borrow on bond markets to finance the remainder of the $1 trillion ambition for infrastructure spending. In effect, close to 14 percent of the investment would come as a no-cost payment to the equity investors from taxpayers. Investors would then obtain streams of income through shares of user fees or from tax revenue via a PPP.

Navarro and Ross believe the tax credits will harness investment because the equity cushion helps ameliorate the large uncertainty associated with infrastructure projects’ costs and usage rates. They also believe the tax credits will be fiscally neutral, with the loss of the income tax base made up for by higher income and corporate income tax revenues associated with the labor and corporations hired to undertake the projects. Coupled with more discipline on construction costs associated with private-sector involvement, the pair believe their tax credit scheme will provide a better deal for U.S. taxpayers than traditional procurement and provision.

As shown, transport infrastructure can no doubt be delivered privately. Major airports are privately owned in a host of advanced economies, as railways and roads have been.100 Although the cost of capital can sometimes be high, particularly given political risks, PPPs can deliver road infrastructure on time and within budget. In Virginia, for example, the Dulles Greenway opened in 1995 having been entirely financed privately. Within that state alone, toll lanes on the Capital Beltway, the Midtown Tunnel, and the Jordan Bridge have all been financed overwhelmingly by private investment.101

There are two questions to consider then. First, will PPPs deliver the types of infrastructure the United States needs now? Second, is the infrastructure tax credit in particular a necessary and desirable policy to achieve the investment?

Provision of infrastructure through PPPs works best when obvious cash streams are associated with the asset. Theory would suggest that allowing private companies to both build and operate an asset with a user revenue stream, even for a fixed period, will incentivize them to consider the long-term maintenance needs of the asset at the point of construction and bear the usage risk.

Cato Institute scholar Randal O’Toole has described these types of arrangements as “demand risk PPPs.” They tend to work well. Clearly though, this form of PPP cannot be applied universally. The more difficult cases include maintenance or upgrading of existing infrastructure, rural roads and bridges, and loss-making modes that are believed to have some broader social benefits. No obvious user fees are associated with them. Indeed, Senate Environment and Public Works Committee Chairman John Barrasso (R-WY) recently expressed concern that PPPs were being touted as a solution to the infrastructure question when they could not deliver these types of projects.

Yet a different type of PPP can be used in areas where user fees are not possible. PPP contracts can be designed such that private investors design, build, operate, own, maintain, and finance an asset and gain revenue from a stream of taxpayer payments for leasing and maintenance services for a fixed period. These are called “availability payment PPPs,” because regular payments from government are conditioned on the asset being available to use at a specified quality, as outlined in a detailed contract.

This type of PPP already exists in the United States for rural transportation. In Pennsylvania, the Rapid Bridge Replacement Project is replacing hundreds of geographically dispersed, structurally deficient bridges with a bundled contract, including maintenance for the next 25 years. Tax revenues provide availability payments.102 Rolling up a significant number of assets in this way can help diversify risks for the private contractor.

The theoretical benefits of this approach are substantial. A large part of the construction and other risks are transferred to the private sector, albeit reflected in higher borrowing costs (a risk premium). Given that the private contractors are paid only when the asset is delivered, timely construction at a fixed price is encouraged. The long contracts should incentivize development with low whole lifetime costs, with the providers assessing maintenance needs in advance. Contracts can also be standardized, with penalties for failure to achieve targets and maintain quality. If many different smaller projects can be bundled in this way, the transaction costs of contract development can be reduced.

The question is whether these benefits overcome the higher borrowing costs the private sector often faces, and whether contracts can be effectively designed. As the CBO has noted, even with these PPPs, taxpayers are still the ultimate source of funds. They just do not face the upfront capital costs.103

Sadly, this “availability payment” model—in which the private contractor gets paid irrespective of usage—has a more mixed record than “demand risk PPPs.” In fact, the United Kingdom made extensive use of this type of agreement in building hospitals and schools through the 2000s under the New Labour government, and the results have been disappointing.

Success in road schemes and a number of privately owned prisons in the early 1990s (with a much higher proportion delivered on time and within budget than through traditional procurement) led to a huge expansion of PPPs in the 2000s. By 2004, they accounted for 39 percent of capital spending by UK government departments, and over 500 were in operation by 2008, including for building schools, hospitals, and public transportation (especially rail). That expanded use of PPPs occurred in part because this type of financing could be done “off balance sheet” for the government (as contingent liabilities), flattering the public finances. At a time when the government was looking for significant capital investment quickly, it appeared to make sense to allow private operators to build new infrastructure with taxpayers in essence paying over time.

Yet this huge expansion of PPPs is now widely regarded as a failed experiment. Any theoretical benefits arising from more innovation, the privatization of risk, and on-time and within-budget delivery of projects (for which some evidence existed104) was eclipsed by the higher borrowing costs in the private sector, the costs of a host of consultants and lawyers in drawing up the contracts, and unnecessarily expensive bundled services.105 The opacity of the liabilities for taxpayers has also proved very unpopular, with various attempts to renegotiate inflexible contracts.

What went wrong? Conservative member of Parliament Jesse Norman believes the government was simply a poor client: