In 2015 the Department of Health and Human Services and the Department of Agriculture released the latest iteration of their dietary advice, Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2015–2020. Upon receiving it, Congress, citing concerns over scientific integrity, commissioned the National Academy of Medicine to review the process of generating those guidelines. In its commission, Congress asked the National Academy of Medicine for full transparency, lack of bias, and the inclusion of all latest available research, however challenging.

By so asking, Congress was suggesting that the federal government’s dietary recommendations — and in particular its long-standing demonization of fats and its praise for carbohydrates — were suspect.

The story starts on January 14, 1977, when the Senate Select Committee on Nutrition and Human Needs published its Dietary Goals for the United States, which, for the first time, attacked overeating. Previously, the Committee had worried about undernutrition, but by the late 1970s it worried that the epidemic of heart attacks could be attributed to an excessive intake of saturated fats. It therefore recommended that Americans eat carbohydrates instead.

Unbeknownst to the vast majority of Americans, however, the theory that replacing saturated fats with carbohydrates would lower the risk of heart attacks was unproven and disputed. Moreover, the government’s dietary advice led Americans to indulge in the widespread consumption of trans unsaturated fats, which are themselves dangerous. Further, this advice coincided with — and probably contributed to — the subsequent epidemics of obesity and type 2 diabetes.

Today, most nongovernmental dietary advice focuses on the benefits of plant-based fats and a Mediterranean diet, and while that, too, may be only a work in progress, it is much better than the paradigm that was disseminated by the government during the 1970s. Yet the government still propagates the oversimplified idea that fats are bad and carbohydrates are good.

In fact, the federal government may be institutionally incapable of providing wise dietary advice, as Thomas Jefferson warned us in his 1787 Notes on the State of Virginia: “Was the government to prescribe to us our medicine and diet, our bodies would be in such keeping as our souls are now.”

Introduction

The federal government’s agencies have been issuing dietary advice for more than a century, but before 1977 they limited themselves largely to addressing malnutrition among the poor. The first two-thirds of the 20th century had witnessed the early triumph of nutrition research when, in a world still concerned with malnourishment, the discipline had helped oversee the discovery of vitamins and the elaboration of the basic principles of metabolic biochemistry. In 1968, the Senate created the Select Committee on Nutrition and Human Needs. At the instigation of its first chairman, Sen. George McGovern (D‑SD) — who was to achieve his greatest prominence when he ran against President Richard Nixon — the committee focused initially on the problems of undernutrition. But a decade later, on January 14, 1977, when it published its Dietary Goals for the United States, the committee launched an attack on the apparent problems of overconsumption. In his foreword to the Goals McGovern wrote:

This is the first comprehensive statement by any branch of the federal government on risk factors in the American diet.

Too much fat … [is] … linked directly to heart disease, cancer, obesity and stroke.

… six out of the ten leading causes of death in the United States [heart disease, cancer, vascular disease, diabetes, arteriosclerosis and cirrhosis of the liver] have been linked to our diet.1

The committee reported unanimously, and in his own foreword Sen. Charles Percy (R-IL) wrote, “without government . . . commitment to good nutrition, the American people will continue to eat themselves to poor health.”2 Consequently, the committee explained, “We as a government . . . have an obligation to provide practical guides to the individual consumer as well as to set national dietary goals for the country.” Accordingly, Americans were urged to:

- Increase carbohydrate consumption to account for 55 to 60 percent of energy (caloric) intake.

- Reduce overall fat consumption from approximately 40 to 30 percent of energy intake.

- Reduce saturated fat consumption to account for about 10 percent of total energy intake.

- Reduce cholesterol consumption to about 300 mg a day.3

The committee had, in short, officially launched the anti-fat, high-carbohydrate campaign that was to dominate the world of nutrition until recently and which still reigns in official circles.

Why Did the Senate Select Committee Launch an Attack on Fats?

The problem was heart attacks. These had seemingly come out of nowhere and by 1968, at the height of the epidemic, accounted for more than a third (37 percent) of all deaths in the United States. By contrast, all cancers accounted for only a sixth (17 percent) of all deaths, and strokes only a tenth (10 percent). Accidents, at 6 percent, were the fourth most common cause of death.4 The sudden epidemic of heart attacks was profoundly alarming, especially as it seemed to target otherwise-healthy people at the peak of their performance.

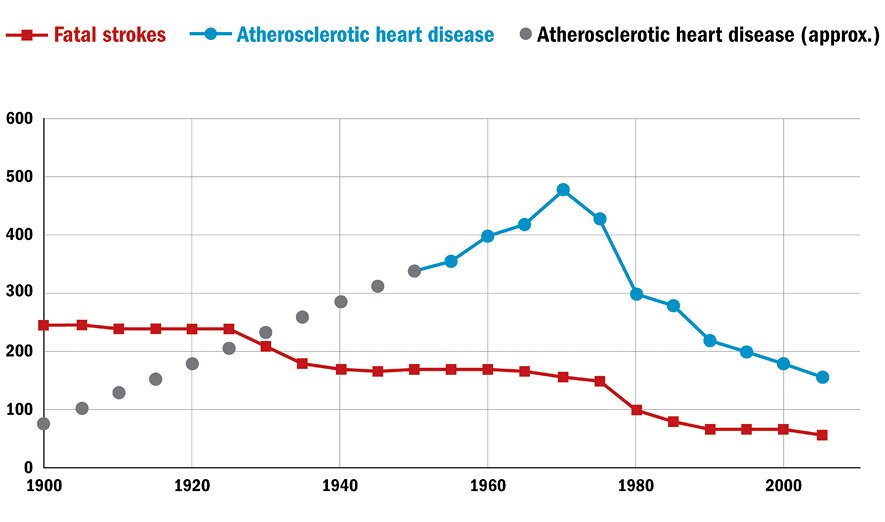

Some physicians argued the epidemic was illusory, the result of better diagnosis and an aging population; yet that argument, although not trivial, was to be disproved. In 1966, for example, Leon Michaels, a Canadian physician, showed that the absence of evidence for heart attacks before the 20th century was indeed evidence for their absence: on comparing the characteristic chest pain of heart attacks with the characteristic pain and symptoms of migraine and gout, he showed that, whereas frequent descriptions of migraine and gout can be found in medical texts from all eras, stretching back to Greek and Roman times, angina and heart attacks started to be described with any frequency only in the 20th century.5 He thus concluded that the death rates from those diseases had increased up to 200 fold between 1901 and 1962, and although that rate of increase cannot be known with certainty, it is now accepted that the rise in the incidence of heart attacks during the 20th century was real (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Death rates per 100,000 people from atherosclerotic heart disease and stroke

Sources: See Daniel T. Lackland et al., “Factors Influencing the Decline in Stroke Mortality: A Statement from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association,” Stroke 45, no. 1 (December 5, 2013): 315–53, doi:10.1161/01.str.0000437068.30550; and Leon Michaels, “Aetiology of Coronary Heart Disease: An Historical Approach,” British Heart Journal 28, no. 2 (March 1966): 258–64.

Note: The data in solid lines come from the joint 2013 statement of the American Heart and Stroke Associations. Data on atherosclerotic heart disease were not collected before 1950, so the dotted lines are extrapolated from the estimates in the Michaels article.

Faced with such an epidemic, some commentators argued it was surely reasonable for the U.S. government to address it. In 1974, for example, Marc LaLonde, Canada’s Minister of National Health and Welfare, had published a working paper, A New Perspective on the Health of Canadians, intended to prescribe the diet of the Canadian people (in which he suggested that Canadians should eat less fat — in particular less saturated fat and less cholesterol — and more carbohydrates) and some commentators argued it was surely not unreasonable for the U.S. Senate Select Committee on Nutrition and Human Needs also to take a position.

It might indeed not have been unreasonable — had the committee’s position been a wise one. Yet the federal government may be institutionally incapable of providing wise dietary advice.

Why the Demonization of Fat?

The senators on the Select Committee were not, of course, nutritionists, so they took their lead from the scientists, and from one scientist in particular: Ancel Keys (1904–2004), professor of physiology at the University of Minnesota. It was Keys who launched the modern dietary era in 1953 when he published his paper, “Atherosclerosis: A Problem in Newer Public Health.”6

By 1953 the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations had collected dietary information on 22 countries. Keys selected data from six countries (Australia, Canada, England and Wales, Italy, Japan, and the United States) to generate his renowned graph, in which he showed that as the percentage of fat in the diet rose, ranging from Japan (7 percent fat in the diet) through to the United States (40 percent fat in the diet), so the death rates from heart disease of males aged 55–59 years rose accordingly, from 0.5 per thousand in Japan to just under 7 per thousand in the United States.

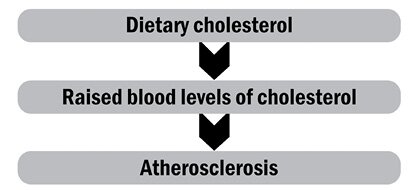

In 1953, as today, heart disease was understood essentially as the consequence of atherosclerosis. But whereas today we understand atherosclerosis to be an inflammation of the arteries, in 1953 it was seen more as a hardening (technically an arteriosclerosis) caused by the deposition of cholesterol within the arterial walls. Keys proposed that as people ate too much fat (in particular too much cholesterol) the blood vessels silted up with cholesterol, leading the heart to become diseased as its own arteries, being narrowed, failed to provide enough oxygen or nourishment. That process in turn would lead to a heart attack or myocardial infarction as the blood clotted over the cholesterol-filled artery and thus killed the patient. Here was Keys’s model:

Initial Criticism of Keys’s Model. It is often forgotten that, from its moment of conception, Keys’s model was heavily criticized: in 1955, for example, the World Health Organization (WHO) convened a small seminar of international experts, who proceeded comprehensively to demolish it (one of his colleagues remembered the WHO meeting as “the pivotal moment in Keys’s life. He got up from being knocked around and said ‘I’ll show these guys.’”).7 Among the critics were Jacob Yerushalmy and Herman Hilleboe, from the University of California, Berkeley, and the New York State Commission of Health, respectively, who attacked the model both at the seminar and shortly afterwards in a paper.8

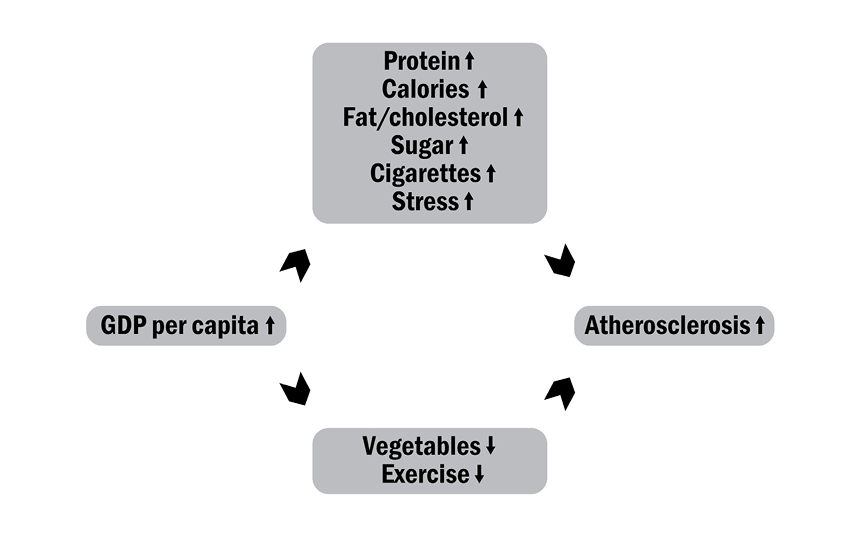

At the 1955 seminar Keys had claimed “there is a remarkable relationship between the death rate from degenerative heart disease and the proportion of fat calories in the national diet,” which was supportable. But then he claimed “no other variable . . . shows anything like such a consistent relationship,” which wasn’t supportable.9 When Yerushalmy and Hilleboe reexamined the Food and Agriculture Organization data, they showed the association between animal protein and heart disease was stronger than between fat and heart disease. And the association between the total consumption of calories and heart disease was stronger yet. Meanwhile, the strongest determinant of calorie and meat intake seemed to be GDP per capita.

On the other hand, consumption of vegetables seemed to protect against heart disease, even though vegetables contain fat, protein, and carbohydrates. To further complicate matters, it appeared that the greater the consumption of animal fat and protein, the lower the death rates from every other condition except for heart disease.

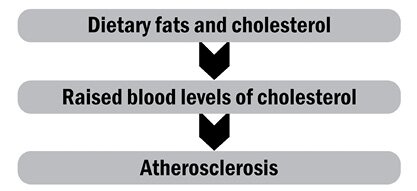

So, the model that best accounted for the empirical facts was:

As Yerushalmy and Hilleboe pointed out at the 1955 WHO seminar, and as they expanded in their 1957 paper, the data thus suggested the citizens of poor countries (who largely ate vegetables, including starchy vegetables such as maize/corn, rice, and potatoes) didn’t die much of heart disease (but they were vulnerable to other diseases); while the citizens of rich countries (who ate a lot of meat, which includes much fat) died largely of heart disease (but were protected from other causes of death).

And to confirm that GDP per capita seemed central to the development of heart attacks, Yerushalmy and Hilleboe noted that atherosclerosis remitted when people reverted to a pre-Western lifestyle: during the Second World War and its aftermath, many parts of Europe had been reduced to meager diets, and those parts of Europe saw their rates of heart disease fall; but when normal food supplies were restored, heart disease returned. Heart disease, in short, seemed to be a consequence of a Western diet (which was in turn a consequence of Western wealth), but no single element of that diet could be identified as especially responsible.

The discussions at the 1955 WHO seminar were prescient, because the delegates saw ischemic heart disease not as the consequence of a single cause (cholesterol) but as the consequence of many complex, still-to-be-elucidated causes. More of those possible causes were soon being identified, and when in 1957 professor of physiology John Yudkin of the University of London reexamined the Food and Agriculture Organization data, he found:

a moderate but by no means excellent relationship between fat consumption and coronary mortality.… A better relationship turned out to exist between sugar consumption and coronary mortality in a variety of countries.10

Yudkin therefore proposed that sugar, not fat, was bad for the heart, and in his book Pure, White and Deadly he wrote of “good nutritious foods like meat and cheese and milk.”11 Also in 1957, in a paper entitled “Dietary Control of Serum Lipids in Relation to Atherosclerosis” published in the Journal of the American Medical Association, Pete Ahrens (1915–2000) of the Rockefeller Institute of Medical Research — the doyen of fat biochemistry — who had long recognized carbohydrates as cardiac killers, was protesting that “unproved hypotheses are enthusiastically proclaimed as facts.”12 (Ahrens was later to greet the Senate Select Committee on Nutrition and Human Needs’ recommendations as treating people as if they were “a homogenous group of Sprague-Dawley rats.”13 ) George V. Mann, a University of Vanderbilt biochemist, was yet another researcher who had shown that Keys’s demonization of animal fats did not fit the cardiac facts.14

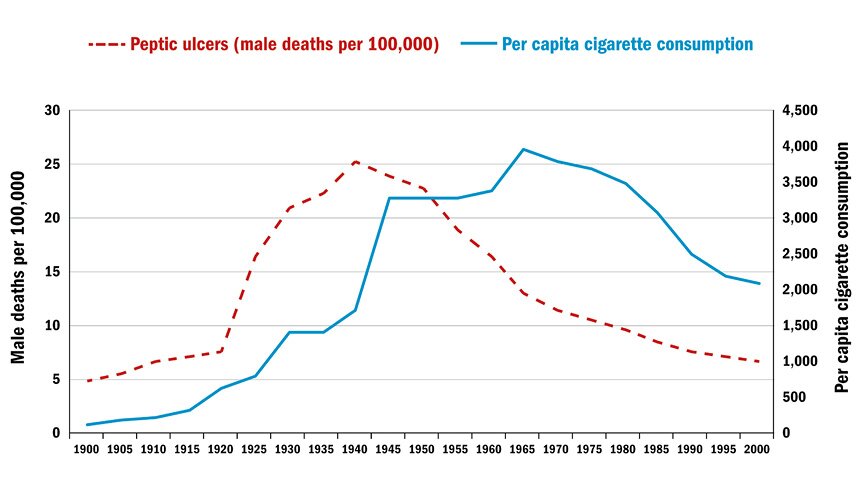

Meanwhile, in 1970, Richard Doll, the epidemiologist who had earlier reported that cigarettes caused lung cancer, found, “It is cigarette smoking . . . which is implicated in the aetiology and manifestation of myocardial infarction.”15 Figure 2 illustrates that one nondietary phenomena that tracks the incidence of atherosclerotic heart deaths is cigarette smoking.

Figure 2: Male peptic ulcer death rates and per capita cigarette consumption

Source: Alexander Mercer, Infections, Chronic Disease, and the Epidemiological Transition: A New Perspective (New York: University of Rochester Press, 2014), p. 184. The data on cigarette consumption come from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Achievements in Public Health, 1900–1999: Tobacco Use, United States, 1900–1999. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (Washington: CDC, 1999): 986–93.

Nor did the list of possible causes stop there, and further causes, including a lack of exercise and excessive stress, were soon identified.

By the 1970s, therefore, the criticisms of the 1955 WHO seminarians had been vindicated, and the only sure model compatible with the data was that found in Figure 3.

Figure 3: Proposed causes of atherosclerosis, circa 1970s

Source: These data have been extracted by the author from the contemporary literature.

But which of the many possible factors was responsible for the epidemic of heart attacks could not be isolated.

So why in 1977 did the Senate committee back Keys’s dietary fat hypothesis against all the other possible causes of atherosclerosis? Well, Keys had generated a model: whereas no one could easily suggest how calories, protein, cigarettes, sugar, a lack of exercise, or a lack of vegetables could provoke atherosclerosis, Keys could suggest how fat could do it.

Keys’s First Model for Atherosclerosis. Keys’s first set of points noted that heart attacks were caused by atherosclerosis; atherosclerotic plaques were full of cholesterol; and patients who suffered heart attacks had elevated blood levels of cholesterol. Keys recommended avoiding cholesterol, noting that rabbits fed high levels of cholesterol develop atherosclerosis.16

Under this model:

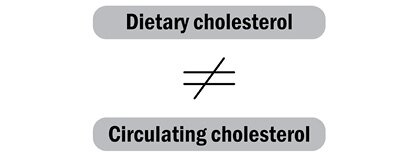

By 1955, though, Keys had appreciated that dietary cholesterol is not a human danger: our livers synthesize most of our cholesterol, and when we ingest it in our food, our livers simply reduce their creation of cholesterol.17 This is not true of all animals, particularly not of herbivores such as rabbits, which — because plants are low in cholesterol — do not normally handle significant amounts of it. So herbivores, when fed high cholesterol in the laboratory, respond with raised cholesterol in the blood: their livers don’t know any better. But we are omnivores, our livers are not naive, and when fed high cholesterol we do not respond with raised levels of blood cholesterol. For us:

Asymmetrical Science

Although by 1955, within two years of originally proposing it, Keys had abandoned the dietary cholesterol hypothesis, for another 60 years the federal government continued to warn against consuming cholesterol-rich foods. It was only in 2015 that its Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee classified high-cholesterol foods such as eggs, shrimp, and lobster as safe to eat: “cholesterol is not a nutrient of concern for overconsumption.”18

This 60-year delay shows how asymmetrical the official science of nutrition can be: a federal agency can label a foodstuff dangerous based on a suggestion, yet demand the most rigorous proof before reversing its advice. The Harvard professor of epidemiology and nutrition Walter Willett, commenting on the asymmetry in a related area of government nutrition advice, described it as “Scandalous. They say ‘You really need a high level of proof to change the recommendations,’ which is ironic, because they never had a high level of proof to set them.”19

And it was Keys himself who championed asymmetry in dietary advice when he wrote in 1957 that nobody had “adequate evidence to state that there is not a causal relationship between dietary fat and the tendency to develop atherosclerosis in man” (i.e., he could condemn fat on the basis of a hypothesis only, yet it could only be classified as safe after exhaustive study).20 So Keys not only launched the cholesterol/fat paradigm on inadequate evidence, he also biased the debate in its favor.

Further, it may seem safer to advise abstention from a particular food than to clear one as safe. Yet this abstention may itself be dangerous, because abstention can have unintended consequences: other foodstuffs must be consumed instead. The Select Committee’s major scientific adviser was Mark Hegsted of Harvard, who wrote in his introductory statement to the Goals of 1977:

The question to be asked, therefore, is not why we should change our diet but why not? What are the risks associated with eating less meat, less fat, less saturated fat, less cholesterol, less sugar, less salts, and more fruits, vegetables, unsaturated fat and cereal products — especially whole grain cereals?21

The answer to this question, namely that it would lead to the eating of more carbohydrates and more trans fats, both of which really are dangerous, would soon emerge. (Trans fats are chemically synthesized unsaturated fatty acids associated with increased risk of coronary heart disease.)

Meanwhile, the 60 years of official misinformation has taken its toll: a 2015 survey by Credit Suisse Foundation (a social research charity) found 54 percent of doctors falsely believed eating cholesterol-rich food raises blood levels of cholesterol and damages the heart. In the words of the survey, “This is a clear example of the level of misinformation that exists among doctors.”22

Keys’s Second Model

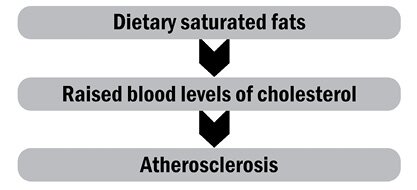

Keys always saw dietary cholesterol as only one of two problematical factors, and by 1955 he was presenting his second set of facts, noting that eating fat, especially saturated or animal fat, raised the blood levels of cholesterol. His recommendation was that we should avoid eating saturated and animal fats.

From this, he generated his second model:

This, of course, was the model the Select Committee was to eventually to endorse in 1977. But as we have seen, on its being presented to the WHO delegates back in 1955, they had immediately been skeptical, noting:

the evidence is circumstantial … no conclusions of etiological [causative] relationships should be attempted unless the factor is found to be related to the disease by evidence [are] from entirely different types of investigations.23

To counter this skepticism, Keys had launched his famous Seven Countries study, published in 1970, in which he personally examined what people were eating in Finland, Greece, Italy, Japan, the Netherlands, the United States, and Yugoslavia. He refined his surveys to look at saturated (i.e., animal) fats rather than total fats in the diet, and yet again he found a strong association between (saturated) fat ingestion and deaths from heart disease.24

But the Seven Countries study wasn’t the “entirely different type of investigation” for which the WHO experts had called, as it still generated data that were, in the WHO experts’ words, only “circumstantial.”25 Indeed, when one of Keys’s colleagues, Alessandro Menotti, recharacterized the foodstuffs in the Seven Countries study, he found “sweets” (sugar-rich products, cakes, and other confectioneries) in the diet correlated more strongly with coronary mortality than did “animal food” (butter, meat, eggs, margarine, lard, milk, and cheese). Even Keys’s own program of work, therefore, suggested it might be carbohydrates, not fats, that killed people.26

Bad Science

The Select Committee’s gravest offense wasn’t going beyond the verifiable science, but actually flouting it. There is in epidemiology a “hierarchy of evidence”: some data are recognized to be more credible than others, and in particular randomized controlled trials (i.e., experiments) are recognized to produce harder data than observations (which may report only associations, and which may, in turn, mislead). By 1977 (when the Select Committee published its report) no fewer than six randomized trials had been performed on a total of 2,467 males (of whom 423 died from heart problems during the trials) in which their total and saturated fat intakes were reduced by placing them on low-fat diets. As predicted by the Keys hypothesis, the subjects on reduced dietary fat showed a fall in their circulating blood levels of cholesterol. But, contrary to the hypothesis, their mortality rates did not fall. In their devastating review of the six trials, freelance nutritionist and author Zoë Harcombe and her colleagues in Wales and Kansas City concluded, “Dietary recommendations were introduced for 220 million US citizens … in the absence of supporting evidence from randomized controlled trials.”27

That lack of hard evidence was recognized at the time, and in 1977 the American Medical Association responded to the Goals with the statement:

The evidence for assuming that benefits [are] to be derived from the adoption of such universal dietary goals … is not conclusive, and there is potential for harmful effects.28

Although the committee had, in its Goals, acknowledged the incomplete state of the science of the day, it had also written with approval:

Marc LaLonde, Canada’s Minister of National Health and Welfare, said: “Even such a simple question as whether one should severely limit his consumption of butter and eggs can be a matter of endless scientific debate … [so] it would be easy for health educators and promoters to sit on their hands.… But many of Canada’s health problems are sufficiently pressing that action has to be taken even if all the scientific evidence is not in.”29

On being challenged on the incompleteness of the science, Senator McGovern said “Senators do not have the luxury that the research scientist does of waiting until every last shred of evidence is in,” which is the opposite of the truth: research scientists are at leisure — and are perhaps even obligated — to explore every possible hypothesis, but senators should not issue advice until every last shred of evidence is in, because they may otherwise issue misleading or even dangerous advice.30 As they did in 1977.

We see here a second reason why official dietary advice may be institutionally biased, because officialdom may be under pressure to issue it prematurely, sometimes even by decades. Moreover, this advice may be based on models rather than on hard facts.

Why Did the Randomized Controlled Clinical Trials Not Confirm the Dietary Saturated Fat Model?

The Keys model was two-staged:

Confusingly, both stages of the model were true. Mark Hegsted, the head of the Department of Nutrition at Harvard and the Select Committee’s major adviser, had shown that when humans ate saturated fat their circulating blood levels of cholesterol did indeed rise. Equally, two future Nobel laureates from Texas, Michael Brown and Joseph Goldstein, showed — in certain inherited diseases of metabolism — that high blood levels of cholesterol can indeed cause heart attacks. So, the committee put two and two together and supposed:

thus reminding us of H. L. Mencken’s aphorism that for every complex problem there is a solution that is clear, simple, and wrong. As we saw above, when no fewer than six randomized controlled clinical trials had tested the complete model by withdrawing saturated fat from the diet of vulnerable men, their blood levels of cholesterol fell but their heart death rates did not. Why not?

It transpires there are at least three different types of circulating blood cholesterol. One type, so-called HDL (high density lipoprotein) is positively healthful, as it draws cholesterol out of the arteries. Another type, lLDL (large low density lipoprotein), is largely neutral, while a third type, sLDL (small low density lipoprotein) is the one that kills, as it (and its oxidized forms) tend to lodge in the arteries and precipitate the inflammation we know as atherosclerosis. Moreover, saturated fat in the diet tends to raise the circulating levels of the essentially neutral lLDLs, while carbohydrate in the diet tends to raise the circulating levels of the dangerous sLDLs. Therefore, it is carbohydrate, not fat, in the diet that raises the dangerous type of cholesterol, although the mechanisms remain to be fully elucidated.

So it is no surprise the six randomized controlled clinical trials failed to find a fall in the rate of heart death rates following the reduction of saturated fat in the diet of vulnerable men. This is because the compensatory rise in carbohydrate intake was dangerous. To Mark Hegsted’s question in his introductory statement to the Goals — “What are the risks associated with eating less meat, less fat, less saturated fat, less cholesterol?” — we can now reply that if, in consequence, people were to follow his advice and eat more carbohydrates and more trans fats in compensation, the risks are of precipitating early death from atherosclerosis. Irony of ironies.

The American People Were Dutiful

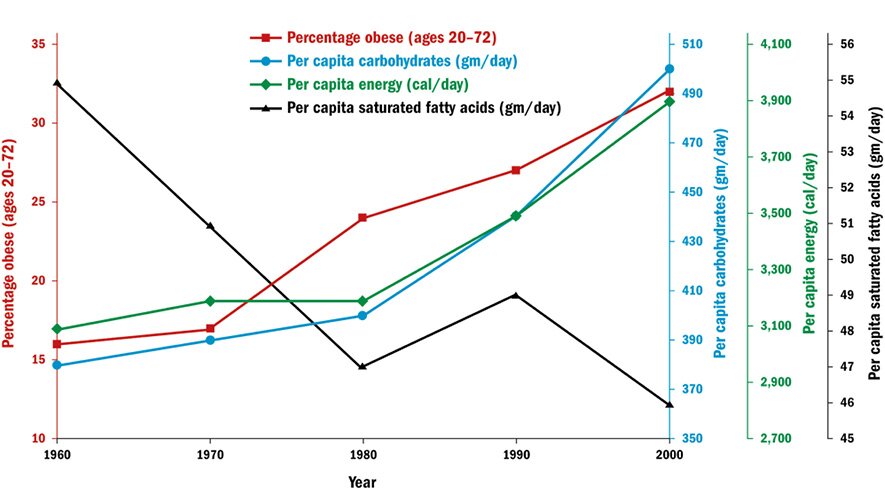

Nonetheless the American people did as they were advised — not just by the government, but also by the mass media, which reinforced the government’s message.31 A survey performed jointly by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute and the Food and Drug Administration showed that, by 1986, 72 percent of adults “believed that reducing high blood levels of cholesterol would have a large effect on heart disease.”32 Consequently, between 1960 and 2000, their per capita consumption of saturated fatty acids fell from 55 to 46 grams per day, and their per capita consumption of cholesterol fell from 465 to 410 milligrams per day. Meanwhile, their per capita consumption of carbohydrates rose from 380 to 510 grams per day and consumption of fiber rose from 18 to 26 grams per day (Figure 4).33

Figure 4: Obesity and the consumption of different foods in America, 1960–2000

Source: The data come from Shi-Sheng Zhou et al., “B-Vitamin Consumption and the Prevalence of Diabetes and Obesity among US Adults: Population Based Ecological Study,” BMC Public Health 10 (2010): 746, https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-10-746.

Americans also increased their intake of unsaturated vegetable-derived fats chemically modified as trans fats (as in replacing butter with margarine) because it was believed that saturated rather than unsaturated fat was dangerous. So whereas in 1911 per capita consumption of butter was 19 pounds a year to 1 pound of margarine, by 1976 butter consumption had fallen to 4 pounds a year while margarine’s had risen to 12.34 We now know that trans fats lower healthful HDLs, raise the dangerous sLDLs, and are inflammatory. Consequently, in the words of a recent authoritative review, they “contribute significantly to increased risk of coronary heart disease events.”35

The Select Committee’s demonization of saturated animal fat can only have damaged the health of Americans who followed its advice by causing them to increase their consumption of trans fats.

Keys and the Select Committee Vindicated? Nonetheless, on following the Select Committee’s advice, an odd thing happened to the American people: their rates of heart disease and stroke fell, really quite dramatically (see Figure 1). So, does Figure 1 vindicate the Select Committee’s advice?

Before invoking Figure 1 as vindication of the Select Committee’s advice, consider Figure 2, which illustrates the course of another 20th-century epidemic, that of peptic ulcers. It is often now forgotten, but the 20th century witnessed an epidemic of peptic ulcers that mirrored that of heart attacks. Since nobody has suggested saturated fat is the cause of peptic ulcers, this must warn us not to confuse correlation with causation: a disease may reflect the incidence of heart attacks without that incidence proving that saturated fat is responsible.

Moreover, the stroke data in Figure 1 are incompatible with the Keys hypothesis. Strokes are caused by the same atherosclerotic process as heart attacks, yet their epidemiology looks different: namely, they peak before the 20th century, and during the first half of the 20th century they appear to decline even in the face of the high-fat Western diet. During the second half of the 20th century they continue to decline, even as the Western diet becomes lower-fat and higher-carbohydrate. Figure 1, indeed, shows that variations in dietary composition cannot explain the epidemiology of strokes.

Strokes and the Metabolic Syndrome

So, how can we explain the epidemiology of strokes? Well, the World Health Organization reports that in 2015, the latest year for which we have data, the two commonest causes of death among low-income economies were chest infections and diarrhea (i.e., bacterial and viral infections of the lungs and guts). But stroke was third.36

Strokes are a disease of poverty, and the British epidemiologist David Barker best explained the association of strokes with poverty when he showed — unexpectedly — a correlation between maternal mortality rates and strokes.37 In his words:

If you want to know how much … stroke there is in any city, any town, any rural village, do not count the hamburger outlets, the tobacconists, the playgrounds. Ask instead how many mothers died in childbirth several years ago.38

Maternal mortality rates are highest where mothers are poor and ill-fed and where, in consequence, their fetuses are malnourished. And a malnourished fetus is a fetus under metabolic pressure, so it must make a choice: which organs will it protect? Will it allow all its organs to be malnourished equally, or will it protect some organs at the expense of others? It appears a malnourished fetus chooses to protect its brain (these responses are little different from an adult’s: when adult mammals are starved, most of their organs shrink, the exceptions being the brain and, in the case of male mice, the testicles).39

So, on being starved, the fetus will deprive its other organs of nourishment, and in consequence it will grow into a short adult; and to help achieve that smallness, it will induce its muscles and other major organs to become resistant to insulin. The role of insulin is to direct the glucose we absorb from our food into our muscles and other major organs, so when we become insulin-resistant, their glucose uptake will be suppressed, thus sparing it for the brain.40 And, unexpectedly perhaps, it transpires that insulin resistance contributes to atherosclerosis.

Malnourished or poor mothers, therefore, produce children who are prone to developing strokes. But well-nourished or rich mothers do not. Hence the slope of the line in Figure 1: as mothers in the West have grown increasingly well-nourished, so their babies have been ever-less prone to developing strokes.

Understanding the Incidence of Heart Attacks in the 20th Century: Summarizing What We Know

From the divergences between the two lines in Figure 1 we can see that the causes of strokes and heart attacks must be different. Although both are caused by atherosclerosis, this condition must affect the arteries of the brain and heart in subtly different ways. All, therefore, we can currently state with certainty is that atherosclerosis is an inflammation of the arteries of which there are many possible causes, including the insulin-resistance of the metabolic syndrome and raised levels of sLDL, but also including smoking, stress, hypertension, diabetes, and aging, as well as a range of inflammatory diseases including arthritis, lupus, chronic infections, and inflammations of unknown cause. Another inflammatory disease that can apparently cause heart attacks is peptic ulceration, which is caused primarily by infection with Helicobacter pylori, because it transpires there is an association between H. pylori infection and atherosclerosis.41 Importantly, therefore, we still cannot know with certainty what accounted for the epidemiology of heart deaths in the 20th century, which must weaken the confidence with which we can pronounce on any putative causative factor.

Shattering the Cholesterol Story

Fifty years after Keys had captured the Senate Select Committee’s imagination, the failings of the cholesterol hypothesis had become so obvious that in 2007 Gary Taubes, a science journalist, could publish a book Good Calories, Bad Calories, which became a bestseller. In the book he claimed that carbohydrates in general, and sugar in particular, were the dietary hazards; natural fats were healthful.42

As we have seen above, there was already a long scientific tradition led by such professors as Yudkin, Mann, and Ahrens arguing for carbohydrates/sugar, not fats, being the cardiac killers, but Taubes also had a populist predecessor, Robert Atkins (1930–2003), who in 1972 had published Dr. Atkins’ Diet Revolution. Atkins was a New York cardiologist who found that, for slimming, a diet low in carbohydrates and high in fat and protein worked.43

While Yudkin, Mann, and Ahrens had focused on sugar/carbohydrates as the cause of heart attacks, Atkins had focused on sugar/carbohydrates as the cause of obesity. And Taubes continued in Atkins’s wake, noting that the epidemic of obesity (and type 2 diabetes) accelerated when fat in food was being replaced by carbohydrate (see Figure 4). Thus, between 1960 and 2000 the incidence of obesity more than doubled, from 13.4 percent of the population to 30.9 percent, while the incidence of type 2 diabetes rose even more markedly, from 2.6 percent to 6 percent of the population. Since 2000 it has continued to rise, and it reaches nearly 10 percent today.44

Yet we should eschew easy myth-making. Thus Jennie Brand-Miller at the University of Sydney, Australia, has shown that in Australia and the United Kingdom, sugar consumption fell between 1980 and 2003 even as obesity rose, which suggests that obesity cannot be attributed to any single nutrient.45 Moreover, a recent massive study of the literature (data on 68.5 million people) found that while overweight (body mass index [BMI] over 25) and obesity (BMI over 30) are — as is widely known — associated with cardiovascular and other diseases, the impact may be less important than is widely feared, and the authors of the study noted that “the rate of this increase has been attenuated owing to decreases in underlying rates of death from cardiovascular disease.”46 Indeed, life expectancies in the United States have continued to rise (as they have continued to rise among industrialized countries since 1840) by three months for every year lived, or six hours for every day lived, which is truly extraordinary.47 Moreover, the so-called “obesity paradox” reveals how, under some circumstances, being overweight can apparently be healthful, and we should remember that as early as 1955 the WHO symposium noted that the Western diet had dual effects in both stimulating and damaging our health.48 We are still trying to understand these effects, and it must be premature to confidently dictate our diet.

There is nonetheless currently a scientific consensus on health and diet, which has been summarized by the American Heart Association:

- Dietary saturated fat does increase the rate of cardiovascular disease significantly (Keys got that right), but

- replacing it with refined carbohydrates and sugars does not reduce the rate of cardiovascular disease (Keys got that wrong, whereas his critics, including Yudkin, Mann, and Ahrens, got that right), but

- replacing saturated (animal) fat with unsaturated (vegetable) fat does reduce the rate of cardiovascular disease significantly (as effectively as does treatment with statins) as long as those unsaturated fats are not trans fats.49

But this consensus has not yet deeply penetrated the public debate, and while most popular commentators now follow the Taubes anti-carbohydrate/anti-sugar story, the federal government and leading medical authorities still follow the traditional anti-fat story.50 This divergence of opinion is both unnecessary and unhelpful.

A Nutritional Note

Reducing food to its constituent chemicals such as carbohydrate or fat is now increasingly criticized as “nutritionism,” because such reductionism may mislead by ignoring the complex and generally unknown interactions between the different chemicals in food.51 So, for example, the data may mean that meat is dangerous not because of its fat content but because of its protein or haem content (haem being the iron-containing chemical in meat that gives it a red color).52 Equally, a Harvard group has identified that plant-based diets that are rich in sugars, starch, or refined carbohydrates may be unhealthful.53

The current American Heart Association advice, therefore, seeks to avoid the nutritionist error by recommending a “Mediterranean” diet (rich in olive oil, vegetables, fruit, nuts, and legumes such as peas, beans, lentils, and chickpeas; moderate in fish, poultry, alcohol, and wholegrain cereals; and low in red meat, processed meat, and sweet foods such as cakes or jams). The similar DASH (Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension) diet is also recommended by the association.54

A Biochemical Note

Taubes suggested that, calorie for calorie, carbohydrates in the diet may promote obesity more than fat does because they stimulate the secretion of insulin, which in turn stimulates adipocytes (fat cells) to store fat: just as a pubertal girl puts on weight around her hips and at her breasts because of the local actions on fat cells by certain female hormones (not because she’s suddenly started to overeat), so someone who swaps fats for carbohydrates may start to put on weight because of the generalized effect on fat cells of insulin. Further, insulin drives down blood sugar levels, which in turn promotes the secretion of hunger hormones such as ghrelin, which therefore stimulates further eating.55

Conclusion

The central question remains: Why, in 1977, did the Senate Select Committee on Nutrition and Human Needs publish its Dietary Goals for the United States when so many credible authorities, including Yudkin, Atkins, Ahrens, Mann, and the American Medical Association, had anticipated, at least in part, today’s understanding of carbohydrates and other saturated fat substitutes as dangerous?

One problem is that scientists are much less scientific than is popularly supposed. John Ioannidis of Stanford University has shown in his 2005 paper “Why Most Published Research Findings Are False” (which has been cited nearly 5,000 times) that the poor application of statistics allows most published research findings to indeed be false, while Brian Nosek of the University of Virginia recently reported — again in large part because of the poor application of statistics — that fewer than half of published studies in psychology can be reproduced.56 Although Nosek’s findings have been challenged, it is now commonplace to describe a “crisis of reproducibility” in science, and mainstream scholars now write articles with such titles as “Saving Science.”57 Too many research papers, in short, cannot be trusted. Why not?

There is a perverse reason that scientists use poor statistics: career progression. In a paper entitled “The Natural Selection of Bad Science,” Paul Smaldino and Richard McElreath of the University of California, Merced, and the Max Planck Institute, Leipzig, found that scientists select “methods of analysis … to further publication rather than discovery.”58 Smaldino and McElreath report how entire scientific disciplines — despite isolated protests from whistleblowers — have, for more than half a century, selected statistical methods precisely because they will yield publishable rather than true results. The popular view is that scientists are falsifiers, but in practice they are generally verifiers, and they will use statistics to extract data that support their hypotheses. Keys, for example, was not a dishonest man, he was merely a typical scientist who had formulated a theory, which — by using poor statistics — he was able over the course of a long career and many publications to appear to verify.

Aggravating the problem of poor science is that research operates a version of public-choice theory: in his 1965 Logic of Collective Action, Mancur Olsen showed how small interest groups can capture public policy, and publicly funded science is no exception. Once armed with power over government-funded research grants, access to peer-reviewed journals, and appointments to university positions, Keys and his fellow elite researchers could enforce their paradigm on the whole field. Which was why the successful paradigm-shifter emerged not as a mainstream scientist but as a journalist — Taubes — who was spared the pressure to conform. And this public-choice aspect of science was aggravated by the Senate Select Committee’s endorsement of the fat paradigm, which fueled it, literally, with public money.

The federal government’s failings were further aggravated by lobbying. When McGovern’s committee reported, the reaction from the meat, egg, and other food lobbyists was so vitriolic that the committee was forced to hold additional public hearings. Following those, a second edition of Dietary Goals for the United States was hurriedly released in late 1977, retracting some of its strongest earlier claims. For example, the committee added this sentence: “science [cannot] at this time insure that an altered diet [will] provide improved protection from killer diseases such as heart disease.”59 As it happened, the meat and egg lobbyists were not wrong in all their objections, but they influenced the committee not because of their superior science, but because of their electoral power.

Because of the controversy, the reputation of the Select Committee suffered, and its mandate was allowed to lapse. The issuance of further federal dietary advice was then charged to the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and the Department of Agriculture (USDA), which have since jointly published, every five years, their Dietary Guidelines for Americans (the most recent was in 2015), which have, however, only reinforced the anti-fat, pro-carbohydrate message of the original 1977 Dietary Goals. This message was to be popularized in the USDA’s Food Guide Pyramid (1992), MyPyramid (2005), and MyPlate (2011).

The USDA was so empowered specifically to help protect agricultural interests, which inevitably has distorted its advice. Marion Nestle, for example, professor of nutrition at New York University, reports that when she was hired to edit the 1988 Surgeon General’s Report on Nutrition and Health,

My first day on the job, I was given the rules: no matter what the research indicated, the report could not recommend “eat less meat” as a way to reduce the intake of saturated fat, nor could it suggest restrictions on intake of any other category of food.60

Indeed, Marion Nestle’s book Food Politics: How the Food Industry Influences Nutrition and Health, was first published in 2002; it is now in its third edition, and it has been cited no fewer than 2,250 times, yet the food industry still influences the federal government’s advice. Thus the New York Times for January 18, 2016, reported that the early drafts of the 2015–2020 Guidelines confirmed that red and processed meats increase the risks of developing bowel and other cancers, but — following the lobbying of Congress by the National Cattlemen’s Beef Association — the reference was removed from the final version.61

The problem of poor science is aggravated in food because of the vast weight of papers (containing highly selective information and highly selective statistics) that are published in distinguished journals by food companies themselves. A recent survey showed, for example, that reviews of the literature authored by scientists with financial links to the sugar industry were five times less likely to conclude that sugar aggravated obesity or weight gain than did reviews authored by independent scientists.62 Where a field of research such as food science can be dominated by producers’ research, therefore, it can be doubly difficult to determine the various sources of bias. And the bias can be secret: we now know, for example, that Mark Hegsted, the Senate committee’s chief scientific adviser, was being secretly paid by the sugar producers to condemn fat and exonerate sugar and carbohydrates.63

Governments may be institutionally incapable of providing disinterested advice for at least four reasons. First, the scientists themselves may be divided, and by choosing one argument over another, the government may be making a mistake. Second, by abusing the precautionary principle, the government may be biasing its advice away from objectivity to risk-avoidance long before all the actual risks have been calculated. Third, because of public pressure, it may offer premature advice. And fourth, its advice will be distorted by lobbying.

Congress has lost patience with official dietary advice, so it commissioned the National Academy of Medicine to review “the entire process used” to generate the official guidelines, although unfortunately the review was limited only to methodology and not results.64 But why should the federal government issue health advice at all? The general public, sadly, will give greater credence to federal government pronouncements than the science can bear, and it would surely be healthier to promote a free market in research ideas. There are a large number of scientific institutions qualified to give advice on food, and it would surely be healthier for the public to be exposed directly to their disagreements rather than for the federal government to proselytize an apparent consensus that, in reality, is only partial and selective.

The tragedy is that food science is, because of the power and money of its commercial sponsors, deeply flawed, yet government — by inserting its own biases — has only amplified that science’s faults. Society does need a truly independent, truly high-powered entity to interrogate food science’s output, but that will have to be sought among the ranks of people like Gary Taubes, who have made a career of probing the biases of science.

There is a tradition of politicians involving themselves in science. From William Jennings Bryan’s attack on evolutionary theory in the Scopes Trial, to Al Gore and Donald Trump distorting modern climate science, politicians inevitably politicize science and almost always get it wrong; Senator McGovern’s actions were only one example of the many that have damaged the credibility of both science and politics. More than 200 years ago Thomas Jefferson warned politicians particularly not to engage with dietary science, and we need to reheed his warning.65

Notes

1 Select Committee on Nutrition and Human Needs, United States Senate, Dietary Goals for the United States (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1977), p. 1, https://archive.org/details/CAT10527234.

2Dietary Goals for the United States, p. v.

3Dietary Goals for the United States, p. 12.

4 U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, Vital Statistics of the United States, 1968: Volume II—Mortality, Part A (Rockville, MD: Public Health Service, 1972), pp. 1–6, www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/vsus/mort68_2a.pdf.

5 Leon Michaels, “Aetiology of Coronary Artery Disease: An Historical Approach,” British Heart Journal 28, no. 2 (1966): 258–64, doi:10.1136/hrt.28.2.258.

6 Ancel Keys, “Atherosclerosis: A Problem in Newer Public Health,” Journal of the Mount Sinai Hospital 2 (July and August 1953): 118–39.

7 Nina Teicholz, Big Fat Surprise (London: Scribe Publications, 2014), p. 36.

8 Study Group on Atherosclerosis and Ischaemic Heart Disease, Proceedings 117 (Geneva: World Health Organization, 1957).

9 Ancel Keys and Joseph T. Anderson, Symposium on Atherosclerosis: Proceedings (Washington: National Academy of Sciences–National Research Council, 1954). Quoted in Jacob Yerushalmy and Herman E. Hilleboe, “Fat in the Diet and Mortality from Heart Disease: A Methodological Note,” New York State Journal of Medicine 57, no. 14 (1957): 2343–54.

10 John Yudkin, Pure, White and Deadly, 2nd ed. (London: Penguin, 2012), p. 86; and John Yudkin, “Diet and Coronary Thrombosis: Hypothesis and Fact,” Lancet II (1957): 155.

11 Yudkin, Pure, White and Deadly, p. 63.

12 Edward H. Ahrenset et al., “Dietary Control of Serum Lipids in Relation to Atherosclerosis,” Journal of the American Medical Association 164, no. 17 (August 24, 1957): 1905-11, doi:10.1001/jama.1957.62980170017007d.

13 Carmel McCoubrey, “Edward Ahrens Cholesterol Researcher, Is Dead at 85,” New York Times, December 16, 2000, http://www.nytimes.com/2000/12/16/us/edward-ahrens-cholestrol-researcher-is-dead-at-85.html.

14 George V. Mann, “Diet-Heart: End of an Era,” New England Journal of Medicine 297, no. 12 (October 1977): 644–50, doi:10.1056/nejm197709222971206.

15 A. E. Bennett et al., “Sugar Consumption and Cigarette Smoking,” Lancet 295, no. 7655 (May 16, 1970): 1011–14, doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(70)91147–5.

16 Gerald Finking and Hartmut Hanke, “Nikolaj Nikolajewitsch Anitschkow (1885–1964) Established the Cholesterol-Fed Rabbit as a Model for Atherosclerosis Research,” Atherosclerosis 135, no. 1 (1997): 1–7, doi:10.1016/s0021-9150(97)00161–5.

17 Ancel Keys et al., “Effects of Diet on Blood Lipids in Man, Particularly Cholesterol and Lipoproteins,” Clinical Chemistry 1, no. 1 (1955): 34–52, http://clinchem.aaccjnls.org/content/clinchem/1/1/34.full.pdf.

18 U.S. Department of Agriculture and Department of Health and Human Services, Scientific Report of the 2015 Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee (Washington: USDA and HHS, 2015), p. 17, https://health.gov/dietaryguidelines/2015-scientific-report/PDFs/Scientific-Report-of-the-2015-Dietary-Guidelines-Advisory-Committee.pdf.

19 Gary Taubes, “The Soft Science of Dietary Fat,” Science 291, no. 5513 (March 30, 2001): 2536–45, doi:10.1126/science.291.5513.2536.

20 Ancel Keys, “Epidemiologic Aspects of Coronary Artery Disease,” Journal of Chronic Diseases 6, nos. 4–5 (1957): 552–59.

21Dietary Goals for the United States, p. 3.

22 Manuel Hörl, “Fat: The New Health Paradigm,” Credit Suisse, September 22, 2015, https://www.credit-suisse.com/corporate/en/articles/news-and-expertise/fat-the-new-health-paradigm-201509.html.

23 Study Group on Atherosclerosis and Ischaemic Heart Disease, Proceedings 117.

24 Ancel Keys, ed., Seven Countries: A Multivariate Analysis of Death and Coronary Heart Disease (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1980). Quoted in Teicholz, Big Fat Surprise, p. 38.

25 Study Group on Atherosclerosis and Ischaemic Heart Disease, Proceedings 117.

26 Alessandro Menotti et al., “Food Intake Patterns and 25-Year Mortality from Coronary Heart Disease: Cross-Cultural Correlations in the Seven Countries Study,” European Journal of Epidemiology 15, no. 6 (July 1999): 507–15.

27 Zoë Harcombe et al., “Evidence from Randomised Controlled Trials Did Not Support the Introduction of Dietary Fat Guidelines in 1977 and 1983: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis,” Open Heart 2, no. 1 (2015): 1–6, doi:10.1136/openhrt-2014–000196.

28 “Dietary Goals for the United States: Statement of the American Medical Association to the Select Committee on Nutrition and Human Needs, United States Senate,” Rhode Island Medical Journal 60, no. 12 (1977): 576–81.

29Dietary Goals for the United States, p. 10.

30 Quoted in Harcombe et al., “Evidence from Randomised Controlled Trials,” pp. 1–6.

31 For an account of the mass media’s support for the government’s message, see Teicholz, Big Fat Surprise, pp. 47–53.

32 Beth Schucker, “Change in Public Perspective on Cholesterol and Heart Disease,” Journal of the American Medical Association 258, no. 24 (December 1987): 3527, doi:10.1001/jama.1987.03400240059024.

33 Shi-Sheng Zhou et al., “B‑Vitamin Consumption and the Prevalence of Diabetes and Obesity among US Adults: Population Based Ecological Study,” BMC Public Health 10, no. 1 (December 2, 2010), doi:10.1186/1471–2458-10–746.

34 Data from the USDA are reproduced in Roberto A. Ferdman, “The Generational Battle of Butter vs. Margarine,” Washington Post, June 17, 2014, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/wonk/wp/2014/06/17/the-generational-battle-of-butter-vs-margarine/?utm_term=.b9b8f2a12ea5.

35 D. Mozaffarian, A. Aro, and W. C. Willett, “Health Effects of Trans-Fatty Acids: Experimental and Observational Evidence,” European Journal of Clinical Nutrition 63, no. S2 (May 2009): S5–S21, doi:10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602973.

36 World Health Organization, “The Top 10 Causes of Death,” http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs310/en/index1.html.

37 C. N. Hales and D. Barker, “Type 2 (non-insulin-dependent) Diabetes Mellitus: The Thrifty Phenotype Hypothesis,” International Journal of Epidemiology 42, no. 5 (October 2013): 1215–22, doi:10.1093/ije/dyt133.

38 Quoted in Caroline Fall and Clive Osmond, “David Barker,” Sight and Life 27 (2013): 64–66.

39 Richard Weindruch and Rajindar S. Sohal, “Caloric Intake and Aging,” New England Journal of Medicine 337, no. 14 (October 2, 1997): 986–94, doi:10.1056/nejm199710023371407.

40 P. L. Hofman, “Insulin Resistance in Short Children with Intrauterine Growth Retardation,” Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 82, no. 2 (February 1997): 402–06, doi:10.1210/jc.82.2.402.

41 John N. Duggan and Anne E. Duggan, “The Possible Causes of the Pandemic of Peptic Ulcer in the Late 19th and Early 20th Century,” Medical Journal of Australia 185, no. 11/12 (December 2006): 667–69; and John R. Brooks and Angelo J. Eraklis, “Factors Affecting the Mortality from Peptic Ulcer,” New England Journal of Medicine 271, no. 16 (October 15, 1964): 803–9, doi:10.1056/nejm196410152711601.

42 Gary Taubes, Good Calories, Bad Calories: Challenging the Conventional Wisdom on Diet, Weight Control, and Disease (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2007).

43 Edgar S. Gordon et al., “A New Concept in the Treatment of Obesity,” Journal of the American Medical Association 186, no. 1 (October 5, 1963): 50–60, doi:10.1001/jama.1963.63710010013014.

44 Robert J. Kuczmarski, “Increasing Prevalence of Overweight among US Adults,” Journal of the American Medical Association 272, no. 3 (July 20, 1994): 205, doi:10.1001/jama.1994.03520030047027; Katherine M. Flegal, “Prevalence and Trends in Obesity among US Adults, 1999–2000,” Journal of the American Medical Association 288, no. 14 (October 9, 2002): 1723, doi:10.1001/jama.288.14.1723; and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Diabetes Statistics Report, 2017 (Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2017).

45 Alan W. Barclay and Jennie Brand-Miller, “The Australian Paradox: A Substantial Decline in Sugar Intake over the Same Timeframe that Overweight and Obesity Have Increased,” Nutrition 3, no. 4 (April 3, 2011): 491–504.

46 GBD 2015 Obesity Collaborators, “Health Effects of Overweight and Obesity in 195 Countries over 25 Years,” New England Journal of Medicine 377, no. 1 (July 6, 2017): 13–27, doi:10.1056/nejmoa1614362.

47 National Institute on Aging, Living Longer 2015, https://www.nia.nih.gov/research/publication/global-health-and-aging/living-longer.

48 Katherine M. Flegal et al., “Association of All-Cause Mortality with Overweight and Obesity Using Standard Body Mass Index Categories,” Journal of the American Medical Association 309, no. 1 (January 2, 2013): 71–82, doi:10.1001/jama.2012.113905.

49 Frank M. Sacks et al., “Dietary Fats and Cardiovascular Disease: A Presidential Advisory from the American Heart Association,” Circulation 136, no. 3 (June 15, 2017), doi:10.1161/cir.0000000000000510.

50 U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and U.S. Department of Agriculture, 2015–2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 8th ed. (Washington: HHS, 2015), https://health.gov/dietaryguidelines/2015/guidelines/.

51 Michael Pollan, In Defense of Food: An Eater’s Manifesto (New York: Penguin Books, 2008).

52 Thomas C. Campbell, “A Plant-Based Diet and Animal Protein: Questioning Dietary Fat and Considering Animal Protein as the Main Cause of Heart Disease,” Journal of Geriatric Cardiology 14, no. 5 (May 2017): 331–37, doi:10.11909/j.issn.1671–5411.2017.05.011.

53 Ambika Satija et al., “Healthful and Unhealthful Plant-Based Diets and the Risk of Coronary Heart Disease in U.S. Adults,” Journal of the American College of Cardiology 70, no. 4 (July 25, 2017): 411–22, doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2017.05.047.

54 Mayo Clinic, “DASH Diet: Healthy Eating to Lower Your Blood Pressure,” April 8, 2016, http://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/nutrition-and-healthy-eating/in-depth/dash-diet/art-20048456?pg=1.

55 Tomomi Shiiya et al., “Plasma Ghrelin Levels in Lean and Obese Humans and the Effect of Glucose on Ghrelin Secretion,” Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 87, no. 1 (January 2002): 240–44, doi:10.1210/jcem.87.1.8129.

56 John P. A. Ioannidis, “Why Most Published Research Findings Are False,” PLoS Medicine 2, no. 8 (August 30, 2005), doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0020124; and Open Science Collaboration, “Estimating the Reproducibility of Psychological Science,” Science 349, no. 6251 (August 28, 2015), doi:10.1126/science.aac4716.

57 Daniel T. Gilbert et al., “Comment on ‘Estimating the Reproducibility of Psychological Science,’” Science 351 (March 4, 2016): 1037; and Daniel Sarewitz, “Saving Science,” The New Atlantis (Spring/Summer 2016): 4–40, https://www.thenewatlantis.com/publications/saving-science.

58 Paul E. Smaldino and Richard McElreath, “The Natural Selection of Bad Science,” Royal Society Open Science 3, no. 9 (September 21, 2016), doi:10.1098/rsos.160384.

59 Quoted in Gerald M. Oppenheimer and I. Daniel Benrubi, “McGovern’s Senate Select Committee on Nutrition and Human Needs Versus the Meat Industry on the Diet-Heart Question (1976–1977),” American Journal of Public Health 104, no. 1 (January 2014): 59–69, doi:10.2105/ajph.2013.301464.

60 Marion Nestle, Food Politics: How the Food Industry Influences Nutrition and Health (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2013), p. 3.

61 Jane E. Brody, “What’s New in the Dietary Guidelines,” New York Times, January 18, 2016, well.blog.nytimes.com/2016/0/18what’s‑new-in-the-dietary-guidelines/r_r=0.

62 Maira Bes-Rastrollo et al., “Financial Conflicts of Interest and Reporting Bias Regarding the Association between Sugar-Sweetened Beverages and Weight Gain: A Systematic Review of Systematic Reviews,” PLoS Medicine 10, no. 12 (December 31, 2013): 1–9, doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001578.

63 Cristin E. Kearns, Laura A. Schmidt, and Stanton A. Glantz, “Sugar Industry and Coronary Heart Disease Research,” JAMA Internal Medicine 176, no. 11 (November 1, 2016): 1680–85, doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.5394.

64 Peter Whoriskey, “Congress: We Need to Review the Dietary Guidelines for Americans,” Washington Post, December 18, 2015.

65 Thomas Jefferson, Notes on the State of Virginia, ed. Frank Shuffelton (New York: Penguin, 1999), p. 165.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.