In 2011, on the heels of the financial crisis and after passing the behemoth known as the Dodd-Frank Act, Congress did something unexpected: it passed, with wide bipartisan support, a piece of legislation that rolls back regulation of the financial sector. In early 2012 President Obama signed it into law. The legislation, the Jumpstart Our Business Start-ups Act, or JOBS Act of 2012, aims to help small businesses access capital by lowering barriers in several areas of the securities laws.

Traditionally, small businesses have relied on personal savings, help from family and friends, and small banks for cash infusions. However, the community banks that have typically provided the bulk of small business loans have been disappearing. Moreover, the fact that the recent crisis originated in the housing market put additional pressure on small business lending since many small businesses use the owner’s home to secure the loan.

While larger businesses have always turned to the capital markets to raise funds, these markets are more difficult for smaller companies to access. Regulation has always been a high barrier to entry, and, until recently, smaller companies have had no means of reaching a large audience of potential investors as publicly owned companies do. The advent of the Internet has, however, removed this second obstacle, and vehicles such as crowdfunding seem tailor-made to meet small businesses’ funding needs. The remaining great barrier was therefore regulation. The JOBS Act takes aim at key regulatory hurdles in several sections of the securities laws, seeking to lower the thresholds to make securities offerings a feasible option for a range of small business models.

Although the JOBS Act has taken important strides toward beneficial deregulation, more work remains to be done. The act’s crowdfunding provision is laden with protections that are likely to make it unworkable. Moreover, the regulations implementing the provision have rendered it even more cumbersome. Other titles suffer from similarly poor implementation. Even though some aspects of the act and its regulations could be improved, the mere existence of deregulatory legislation aimed at small business and financial innovation is encouraging and can serve as a template for other deregulatory attempts going forward.

Introduction

Small businesses have been called the backbone of our economy,1 the nation’s job-creation engine,2 and the ultimate expression of American individualism and entrepreneurial spirit.3 They comprise a wide array of business models, providing a myriad of goods and services, making them fertile ground for innovation. Indeed, small businesses are vital to our country’s growth and prosperity. The vast majority of American companies are small businesses, including 99.7 percent of U.S. employer firms.4 They produce roughly half of the country’s GDP, and the majority of Americans work for small businesses. Clearly, any plan to improve our long, slow climb out of the economic doldrums that have followed the Great Recession must include nurturing small business development.

This development requires capital. Traditionally, small businesses have relied on owners’ personal savings, personal credit cards, and bank loans. Unfortunately, the community banks, which have been the biggest providers of small business loans, are disappearing. The total number of community banks has fallen from more than 14,000 in the mid-1980s to fewer than 7,000 today.5 Since 1994, the share of U.S. banking assets held by community banks has decreased by more than a half, falling from about 41 percent to 18 percent.6 Many have been swallowed by bigger banks, while others failed in the Great Recession. The remaining small banks, responding to both new regulation, including the Dodd-Frank Act, and ongoing regulatory uncertainty in the banking sector, have tightened standards and conserved capital. The large banks, meanwhile, have been quietly shuttering their small business lending programs, finding them to be unprofitable. Both the decline in community banking and the increased hesitancy among major banks to lend to small businesses may have contributed to the decline in small business loans from 50 percent of all bank loans in 1995 to only 30 percent in 2013.7

The other major source of capital is the sale of securities. A company may choose to “go public” and sell its securities (typically stock) in the public capital markets following a registration of the offering with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). A company may also choose to forgo the expense and hassle of a public offering and instead opt for a private placement or other sale that relies on provisions in the securities laws exempting certain sales from full registration requirements.

While selling securities can be a very attractive option, and is almost always necessary for companies that grow to a certain size, it has considerable drawbacks.8 The laws governing the issuance, sale, and resale of securities are notoriously complex and can trigger significant liability, including criminal liability, if handled improperly. Large companies are subject to virtually the same laws and same liability as small companies, but because much of the compliance cost is fixed, the cost as a percentage of the total capital raised through any given offering of securities is higher for smaller issuers. Additionally, the trend in recent years has been to increase the regulatory burden on many types of securities offerings.

Small companies have therefore faced a double whammy when looking for capital: the contraction of bank lending to small businesses and the increase of regulation in the securities markets. In addition, while the traditional sources for capital have remained stagnant, the diversity of business models that make up the universe of small businesses has expanded rapidly since the advent of the Internet. Bank lending, with its need for hefty documentation, may simply be inappropriate for some types of newer start-up enterprises. Small businesses need other options.

In 2012, Congress passed the Jumpstart Our Business Startups Act (JOBS Act) designed specifically to address the capital needs of small companies. This legislation includes a number of provisions, ranging from a phased-in initial public offering (IPO) process to a new crowdfunding exemption. The JOBS Act is unusual in that, in each of its titles, it pares back regulation, allowing companies additional freedom in pursuing capital. Neither the JOBS Act itself nor its implementing regulation is ideal, but it provides an excellent model for how to identify and repeal purported “protections” that are effectively protecting the economy from growing. It is also a tentative step toward addressing the need for diversity in funding options that reflects the diversity in small business itself.

What is Small Business?

What constitutes a small business is often difficult to define, although several organizations have tried. The federal Small Business Administration has more than 70 categories of small businesses, with specific qualifications based on revenues and number of employees.9 The Small Business Act of 1953, on the other hand, defined small business more qualitatively, as an entity that is independently owned and operated and is not dominant in its field of operation.10 The Internal Revenue Service takes a more quantitative approach, defining small business as partnerships and corporations with assets of $5 million or less, or any sole proprietorship.11 A commonly cited definition is any firm with fewer than 500 employees.12 The mechanic down the street whose business has been passed down through three generations, the law firm with five lawyers, the mom who makes jewelry in her basement to sell online, the three college friends building an app in a garage, and the manufacturing plant with a hundred employees are all small businesses. These businesses differ in size, capitalization, structure, and lifecycle. This heterogeneity complicates the discussion of small-business capital access because the needs of small businesses are not uniform, nor is the suitability of different types of capital.

Whether a certain type of capital will be appropriate for a company will depend on factors such as how the company plans to use the capital, what the company’s anticipated growth trajectory looks like, how the company is structured, and other factors that are only loosely related to the company’s annual revenues or number of employees. One important distinction is between established companies and start-ups.

An established company may need capital to manage cash flow, invest in advertising or new hires, or to expand. But, while the company may grow to some extent, it is unlikely to have exponential growth or to grow beyond the small business classification. The established company will typically have a considerable amount of financial documentation, including bank statements, a credit history, and several years of revenue. In addition, owners and management at established companies generally have several years of experience in the field, and often many years of experience running this particular business in this particular location.

Start-ups, on the other hand, have very little to show beyond an idea, the skills and experience the management brings from other ventures, and possibly a limited proof-of-concept or a small revenue stream. While the start-up’s founders may have quite sophisticated expertise in certain areas, the team may lack the kind of operational and management experience necessary to launch a successful venture. This may be especially true of the start-up with large, public-company aspirations. Also, while an established company may need modest amounts of capital on a periodic basis if it is using the capital to manage cash flow, a start-up typically needs large injections of cash at a few major inflection points that mark the company’s biggest growth spurts.

Given the diversity of business models used by small firms, adequate access to small business capital relies on a nimble marketplace that can leverage new technology and innovative solutions. This will be a marketplace that greets such innovation warmly, and not one that stifles it under an antiquated regulatory regime.

Sources of Small Business Capital

To understand the current strictures on small business capital access it is necessary first to understand where small businesses have traditionally obtained capital. Small business capital options exist on a continuum from the easily accessible and easily controlled, but also typically very limited, personal assets of the owner or retained company earnings, to the difficult to access and control, but exponentially larger assets of the capital markets.

On the personal side, the owner may use savings and credit cards, possibly pooling these with co-owners to amass seed money.13 (According to a National Small Business Association survey, 36 percent of small businesses used personal credit cards; 18 percent received a loan from friends and/or family in 2014.14) If these fall short, the owners may ask friends and family for informal loans or investments. These types of investments can prove tricky for many new business owners. Founders unfamiliar with securities law may not realize that asking a relative to invest in a company is the sale of securities, typically of something akin to common stock, and therefore puts the founders and the company at risk of violating federal and state securities law. These investments, while not fatal to the company, often create stumbling blocks later on as the company grows. Future investors will likely insist that these improperly made investments be unwound, requiring rescission offers to the founder’s mom and dad, rich aunt, and other family and friends who helped get the company off the ground.

Bank lending is also common among small businesses. Loans may be provided by banks of any size, but small banks provide a larger proportion of loans under $1 million and under $100,000. In 2011, banks with assets of $250 million or less accounted for 4 percent of total U.S. banking assets, but made 13.7 percent of business loans for less than $1 million and 13.9 percent of all loans for less than $100,000.15 The 2014 National Small Business Association report showed that 20 percent of small businesses received a loan from a community bank in 2014, while 17 percent had received a loan from a large bank.16 The process of securing a loan can be time-consuming for the small business owner. It typically requires the owner to complete an application and to provide information including personal history (credit history, criminal record, business experience), personal financial and bank statements, the business’s credit history, business licenses, tax returns, a business plan, legal documents such as articles of incorporation and key contracts, as well as additional materials that may be required by individual institutions.

Additionally, in many cases a small business will be required to post collateral of some kind to secure the loan. If the company owns assets, such as equipment or real estate, these may be sufficient. If the company does not own assets sufficient to secure the loan, the business owner may post personal assets, including real estate such as a family home. The federal Small Business Administration also operates programs that provide guarantees to assist small businesses in obtaining loans for which they might not otherwise qualify.17

Once the application has been submitted it may take the bank several months to make a decision on whether to issue the loan. If the application is rejected, the company will have to start the application process anew with another bank.18 It has been estimated that the process of applying for a small business loan can take as much as 20 hours of work on the part of the business.19 The long delay in waiting for a decision, plus the prospect of applying to another bank and waiting on that bank’s decision, can make bank lending unattractive for rapidly growing companies. Additionally, because of the hefty documentation required by banks, a bank loan is generally a better fit for an established company looking to grow than for a start-up looking for seed money.

If a company is unable to access sufficient capital by drawing on the owner’s personal assets and is unable or unwilling to take out the types of loans described above, the company will look for outside investment. Offerings of securities in the United States are governed at the federal level by the Securities Act of 1933 (“the Securities Act”). In general, a company issuing securities must register the offering with the SEC or the offering must qualify for an exemption. Full registration with the SEC allows a company to sell its securities to the general public and allows buyers of these securities to sell them freely in the secondary market. Because registration with the SEC can be extremely costly due to the number and complexity of the required disclosures, a company that goes public has typically grown to such a size that it needs to sell its securities in the public markets to raise sufficient capital to ensure its continued growth.

Once a company makes an initial public offering it becomes subject to a further regulatory regime requiring periodic financial disclosures—for example, the annual report or Form 10‑K, and the quarterly Form 10‑Q—as well as disclosures of certain major company events on an ongoing basis. It must also disclose sensitive information about the company’s business model and operations—information that can be very useful to competitors.

As with most regulatory regimes, failure to comply carries a range of possible penalties, opening the company and its officers, directors, and hired experts to varying degrees of liability, criminal and civil, both to the government and to individual plaintiffs. Given the cost, regulatory burden, and potential liability, a company will typically pursue an IPO only when it is seeking a very large raise—usually in the eight- or nine-figure range.

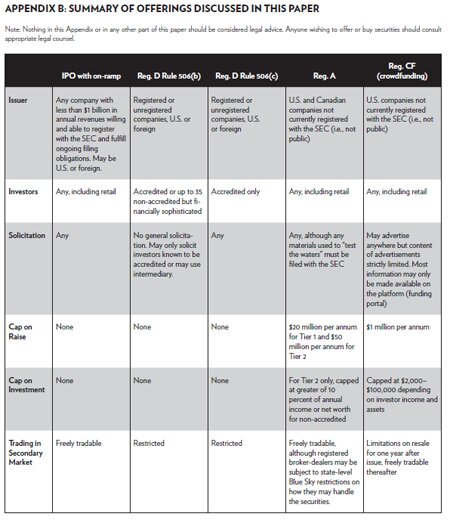

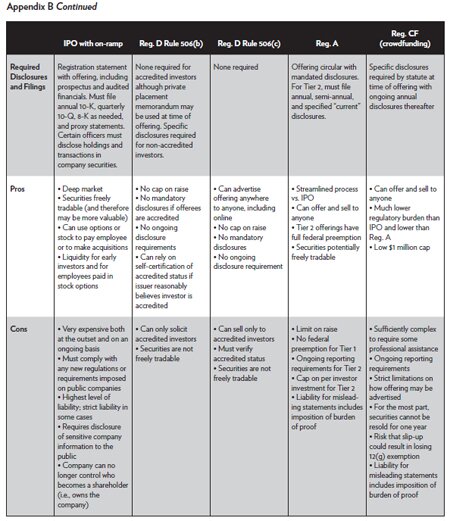

But a public offering is not the only way to obtain investment. The basic principle underlying the regulation of securities in the United States is this: any offer or sale of securities to the public must be registered with the appropriate state and federal regulators or qualify for an exemption. While the public offering—one duly registered with the proper authorities—is perhaps the best-known to those outside the securities world, there are several exemptions that permit the issuance of securities with only limited disclosures to the SEC and investors. Each exemption includes its own set of rules and its own set of pros and cons. Many of these are specifically aimed at providing access to capital for issuers who find an IPO to be a poor fit. The JOBS Act includes a number of changes that specifically target exemptions attractive to small businesses with the goal of making these exemptions more effective and more user-friendly.

Effect of the 2008 Financial Crisis on Small Business Capital Access

As we have seen, small businesses tend to turn to small banks when seeking loans. The average small business loan is a few hundred thousand dollars,20 and more than half of small business loans in 2012 were issued by banks with less than $10 billion in assets.21 Small banks were in decline even before the financial crisis, but the crisis accelerated their demise. Of the 325 banks that failed during the crisis, 263, or 81 percent, were community banks, typically defined as banks with assets under $1 billion.22 Surviving banks tightened lending, both in response to economic uncertainty and to pressure from regulators to maintain higher capital levels and impose more stringent lending standards. The remaining community banks have seen their share of small business lending shrink 21 percent since 2000.23

While some small banks have simply closed, many were absorbed by larger banks. According to a Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City report, 90 percent of the 1,500 bank mergers since 2007 involved a bank with less than $1 billion in assets.24 Although a large bank may keep its small bank acquisitions open as branch offices, large banks’ business models are often not compatible with the realities of small business lending. In particular, large banks, those with more than $10 billion in assets, tend to be formulaic in their approach to lending, using credit scores such as PAYDEX or FICO and financial statements to make their determinations. In a large, widely dispersed organization, such quantifiable methods of decisionmaking are essential to ensure management can evaluate performance and maintain control across branches. Community banks, however, are more likely to have formed relationships with their business clients. They are also likely to be attuned to the community’s economic health, and therefore can assess whether a loan applicant with a low credit score or unattractive financial statements may nonetheless be a good credit risk.

And then there were the effects of the housing market. Although the focus during and after the crisis has been on foreclosures and mortgage delinquencies, plummeting home values were also devastating to small business lending. As property values fell so did the value of loans that could be secured by home equity, as well as the number of houses that could support a second mortgage.

Through the end of the recession and into the early 2010s, options for small business capital looked very much the same as they had for the past 75 years. Funding options included personal savings and credit cards, loans often secured by the family home, and access to the capital markets through channels largely unchanged since the federal securities laws were written in the early 1930s. But even these options were narrower than they had been in earlier years. Credit had tightened in the crisis. Home values were down and small banks were disappearing. Going public had become increasingly unattractive to small companies, given the increase in regulatory compliance cost. There were, however, innovations underway in other sectors that would eventually make their way into the small business capital market.

The Jumpstart Our Business Start-Ups Act of 2012

In response to tightening credit markets, especially in the small business sector, Congress passed the Jumpstart Our Business Startups Act in late 2011; the act was then signed into law by President Obama in early 2012. The act is a mishmash of provisions aimed at helping smaller companies. What is remarkable about it is that each provision actually reduces some part of the regulatory burden. Given the overall trend toward increasing regulation in the financial sector, and the acceleration of this trend coming out of the Great Recession, it is stunning that this act was passed at all—and more stunning still that it passed with overwhelming bipartisan support.25

The act incorporates several concepts already emerging at the time, including most notably a new crowdfunding exemption under the federal securities laws. Other key provisions, described in detail below, include a modified IPO process for smaller companies, changes to the private placement exemption, changes to reinvigorate the exemption under Regulation A, and a provision that expands the number of shareholders a company may have before it is required to register as a public company. The provisions are only loosely related to one another, but they all relax securities regulation in ways intended to benefit small businesses.

This diversity in approaches may be the act’s greatest strength. As discussed above, there is no dominant model when it comes to small businesses; the category includes firms using a wide array of models and organizational structures. The provision of adequate capital for such varied business models will require a broad range of capital solutions. Each of these provisions offers something different, and valuable, to smaller businesses.

To fully understand how the act assists in capital formation, it is useful to review each of the provisions individually. The next several sections of this paper will walk through each provision in turn, examining how various exemptions worked prior to the JOBS Act’s passage, what changes the act made, and how these are likely to play out. Each section concludes with a number of policy recommendations aimed at making the changes initiated by the JOBS Act more effective and removing unnecessary barriers to small business growth.

Title I: The IPO On-Ramp

Title I of the act creates a modified IPO process, nicknamed the “IPO on-ramp” because it offers companies the option of scaling up their disclosure and compliance process gradually. This provision grew out of concern that companies, especially smaller and younger companies, were delaying IPOs or forgoing them altogether due to increased regulatory complexity and risk. The on-ramp is designed to make the process of going public easier for those companies that are otherwise ready for the public markets but that may be shy of taking the plunge.

This provision creates a new “emerging growth company” (EGC) designation that applies to companies with less than $1 billion in annual gross revenues and provides up to five years of forbearance from certain reporting requirements leading up to, during, and immediately after the company’s IPO. 26 Among the key features of the title are the ability to pitch the IPO to institutional investors before filing papers with the SEC (a process known as “testing the waters”); to initiate the IPO process confidentially; and to opt out of certain Sarbanes-Oxley and Dodd-Frank provisions related to accounting disclosures and executive pay disclosures, respectively. The provision also permits research analysts employed by the underwriter to publish research reports immediately upon the earnings release, instead of requiring the analysts to wait a specified number of days.

Given the $1 billion cap, the EGC designation applies to a number of companies that few would consider to be “small” businesses. In fact, companies qualifying as EGCs include the vast majority—80 percent—of companies that have gone public since the on-ramp went into effect in 2012. The on-ramp may therefore best be understood as a measure to increase the attractiveness of IPOs in general, although several of its provisions are especially appealing to smaller companies.

The IPO on-ramp, unlike other provisions in the JOBS Act, required no implementing rules before becoming effective. Although it has been only three years since the act was passed, there are indications that it has succeeded in its goal of increasing the number of IPOs, with the greatest increase among smaller firms and especially among biotechnology firms. Because the equities market has been so bullish in the years since the JOBS Act was passed, it is difficult to say with certainty how much of an effect the act had independent of market forces. However, some evidence supports the conclusion that, controlling for market conditions, the IPO on-ramp accounts for an increase of 21 IPOs, or 25 percent, over pre–JOBS Act levels.27

The on-ramp’s appeal was intended, in part, to derive from the ability to pursue a more streamlined disclosure process.28 The average cost of an IPO has been estimated at about $3 million, with the bulk of this expense going to the lawyers and accountants who prepare the filing documents .29 Whether the offering is for $10 million or $100 million, the work required to prepare these materials remains relatively fixed. The ability to opt out of some legal disclosures was intended to reduce the compliance cost and therefore render those costs a smaller percentage of the overall IPO cost.

Ultimately, however, the reduced disclosure has not been the provision’s most attractive feature. Despite the fact that EGCs can, for example, file only two years of audited financial statements instead of three, in 2013 a small majority of companies opted to provide a full three years instead.30 Additionally, some research has shown that companies that opt for reduced financial disclosure see their IPOs underpriced compared with other issuers.31 It therefore appears that the market itself has demanded a higher level of disclosure, providing a useful test case to demonstrate both what information is truly valuable to investors and the ability of the market to induce such disclosures without regulatory coercion.

On the other hand, the confidentiality provisions have been enormously popular. Uptake on the option to file confidentially has been high, at 88 percent overall since the JOBS Act was signed into law, with many firms also taking advantage of the opportunity to test the waters with institutional investors.32 These provisions provide several benefits. First, preparing for an IPO and filing the necessary papers with the SEC is incredibly expensive. If a company is able to test the waters with institutional investors first, it can spend the money for the IPO with confidence that the IPO will be successful. Second, public filing exposes many of the company’s secrets, including business model, revenue, expenses, information about its products, and management’s view of risks facing the company. A company choosing to go public has calculated that exposing this information publicly, including to its competitors, is worth the opportunity to access the capital markets. If the IPO flops, however, the company has exposed itself for nothing.

In some ways, the confidentiality provisions of the IPO on-ramp seem counterintuitive. The very nature of a public company is that it cannot be secretive. Even without SEC-mandated disclosure, a publicly traded company would need to provide visibility about its operations to shareholders and would-be investors. However, by shifting certain disclosures—including most notably the fact that the company is contemplating an IPO—to just a few weeks later, the company is able to conduct a more accurate cost-benefit analysis regarding the utility of an IPO.

Even though the smallest and youngest companies will not be using the IPO on-ramp any time soon (and some may never opt to go public), the benefits of an improved IPO process inure to companies at every stage. A robust IPO market has several advantages. It reflects economic growth and provides assurance that regulatory barriers are not smothering activity. It has a democratizing effect on wealth-building by enabling non-accredited investors (also known as retail investors) to participate in a company’s explosive early growth. And it lowers the cost of capital, including early stage capital, by providing liquidity for investors. A sluggish IPO market can make it especially difficult for start-ups to raise cash. Such early investment essentially locks down investors’ money. The longer the path to an IPO, the longer investors must wait, and the longer the lag until they are able to recover their cash and invest in a new venture. The IPO on-ramp is therefore especially important to the start-up model small business that must raise cash in a few large injections to make the leap from one stage of growth to the next.

The IPO on-ramp ultimately makes only minimal changes to the IPO process. After five years of going public, a company that uses the on-ramp will have the same reporting and compliance requirements that any other public company has.33 Although regulation generally operates as a ratchet, moving only toward more regulation, in this case regulation was loosened, with limited ill effects and with promising indications of positive results.34

Policy Recommendations

The IPO on-ramp provides not just a single alternative IPO process, but a menu of options from which an issuer may choose. The selection process provides valuable insight into what features are useful to issuers and what features are irrelevant given market pressures. The fact that the confidentiality features appear to be especially attractive to biotechnology companies, who face substantial risk in exposing company secrets during the IPO process, suggests that a one-size-fits-all approach to disclosure may be harmful to capital formation.

It would benefit all public companies, investors, and the American economy if the SEC required only those disclosures that provided valuable information to the market. There is currently no mechanism to systematically revisit and evaluate the effectiveness of the disclosures the SEC requires of public issuers. The effectiveness and lack of evidence that fraudulent offerings increased following the introduction of Title I of the JOBS Act shows that parts of the current mandatory disclosure regime are unnecessary.35 What other parts are equally useless? What serves only as a drag on the economy? A good start to finding out would be a one-time review by the SEC of the current disclosure regime accompanied by a commitment to repeal any requirements that are not shown to be effective. A better start would be to commit to repeating this process on a regular basis to ensure that whatever disclosures the SEC requires are indeed providing value to the market.

Title II: Private Placements

Of the many exemptions from registration available under the federal securities laws, the exemption for private placements is the 800-pound gorilla. This exemption allows issuers to offer securities to a select group of investors, known as “accredited” investors, comprised principally of institutions and wealthy individuals. While the public capital markets receive the most attention, private placements are a key driver of capital access for companies of all sizes. Although the rules for their use are complex, the process is simpler and cheaper than the process for a public offering. While public companies can and do use private placements, the majority of these offerings tend to be in the $1–5 million range, indicating wide usage by small, privately-held companies. Private placements are the way that small companies sell securities to raise capital.

Title II of the JOBS Act liberalizes both the way in which a company doing a private placement may advertise its offering to potential investors and the way in which securities bought in a private placement may be advertised in the secondary market. Given the large role private placements play in funding small companies, principally through investment by venture capital funds (VCs) and angel investors, but also in friends and family rounds, these changes may prove significant.

How Private Placements Are Used

The securities laws make a distinction between “public” and “private” offerings. Public offerings are those made to the general public. Private offerings are those made to a more select group of potential investors. Finding the line between public and private can be tricky—how select does the select group have to be for the offering to qualify as non-public? The vast majority of private placements therefore use a set of rules set out in the SEC’s Regulation D that provide what is known as a “safe harbor.” A safe harbor is a legal provision that states that certain conduct will be assumed not to violate a particular law. It is the rules that make up this safe harbor (and, very specifically, how the rules define “non-public”) that the JOBS Act changes. In order to understand the impact of the changes in Title II of the JOBS Act it is necessary first to understand something about how Regulation D works. Although Regulation D includes several rules with varying requirements under which an offering may qualify for the exemption, the most commonly used, by far, is Rule 506.36

The sine qua non of the registered public offering is its large volume of mandatory disclosures. A company preparing for an IPO often spends millions of dollars compiling specific pieces of information required by law to be provided to the SEC and the public in conjunction with the sale of its securities. Thereafter, the company must spend millions more dollars providing updates on this information to the public (and the SEC) on a quarterly and annual basis. The SEC has estimated that the average cost of continuing annual regulatory compliance for public companies was $1.5 million in 2014.37 The purpose behind these disclosures is to ensure that the investing public has the information it needs to make informed investment decisions.

The presumption underlying Rule 506 is that certain investors, because of wealth or access to information, do not need the protections of the disclosures required in a registered offering.38 And an offering to them may therefore be done under the private placement exemption. Under 506(b), the securities may be sold to no more than 35 “non-accredited investors” and an unlimited number of “accredited investors.” Accredited investors include those investors who are presumed able to “fend for themselves” in obtaining necessary information from the company to make an informed investment decision.39 These investors include institutional investors, a director or executive of the issuer, or a wealthy individual whose assets (excluding primary residence) exceed $1 million or who, alone, earns more than $200,000 annually or $300,000 annually jointly with a spouse.40

Non-accredited investors are individuals who nonetheless have “such knowledge and experience in financial and business matters that [they are] capable of evaluating the merits and risks of the prospective investment, or the issuer reasonably believes immediately prior to making any sale that such purchaser comes within this description.”41 Additionally, sales to these individuals must be accompanied by significant disclosures outlined in Regulation D.42 The rationale for these disclosures is that, unlike accredited investors, non-accredited investors—even those who have “experience in financial and business matters”—are presumed to lack the financial sophistication necessary to request the relevant disclosures from the issuer.43 Because the purpose of most offerings under Rule 506 is to avoid costly disclosures, these offerings are typically limited to accredited investors in order to dispense with the obligation of providing the mandated disclosures for non-accredited investors.44

Unlike other exemptions in the securities laws, there is no limit on the amount of money an issuer can raise using Rule 506 of Regulation D, and it is available for use by public companies.

In addition to restricting who may buy the securities, Rule 506 restricts how an issuer may contact potential buyers. Before Title II of the JOBS Act became effective, issuers relying on Rule 506 were barred from “general solicitation.”45 In interpreting what constitutes a general solicitation, the SEC has taken a broad view. The rule states that general solicitation includes, but is not limited to, “any advertisement, article, notice or other communication published in any newspaper, magazine, or similar media or broadcast over television or radio; and … [a]ny seminar or meeting whose attendees have been invited by any general solicitation or general advertising.”46 Generally, if the issuer has a “preexisting and substantial relationship” with anyone to whom the securities are offered, the SEC will find that there was no general solicitation.

One of the major challenges for companies raising capital through a private placement is attracting investors. A large, established company will have a ready network of brokers and interested investors, something smaller companies, and small young companies in particular, lack. The restrictions on general solicitation therefore put many companies in a bind—how to find accredited investors if the company is barred from advertising for them? There have traditionally been a few options. A company whose owners have wealthy friends or family can tap the owners’ personal networks. There is also considerable informal investment in the small business world, much of which is not in compliance with the securities law. Small business owners may obtain investment from friends and family who are not accredited, often without the small business owner or the investors realizing they are engaging in a securities transaction and certainly without knowledge that they are doing so in violation of the law.

Issuers can also use a middleman: a broker can act as an intermediary to connect issuers with investors. Brokers, knowledgeable about their client’s assets and therefore whether they qualify as accredited investors, and having a preexisting business relationship with their clients, may contact clients who may have an interest in certain private placements the broker knows are seeking investors. However, brokers typically receive a portion of the sales proceeds as a fee, and most small offerings are too small to attract the interest of intermediaries; only 13 percent of Regulation D offerings from 2009 to 2012 reported using a broker.47

There also are investors who intentionally seek out promising new companies with the intention of providing funding via private placement. Venture capital funds are perhaps the best-known of this type of investor. Venture capital firms seek to invest in high-growth companies that can bring an IPO to market in a few years, providing a substantial return on investment.

These companies are generally highly scalable, offering exponential growth if successful. Obtaining VC funding is something of a Holy Grail in the start-up world, but such funding is difficult to obtain. In 2010, for example, 505,473 new companies were incorporated in the U.S. but only 1,095 companies received venture capital funding.48 Because the funds are looking for a large return, given the riskiness of the investment, a business model that is not particularly scalable will not be attractive to venture capital.49

Moreover, some companies do not want venture capital. In exchange for what is a large investment, given the relatively small size of the company, VC typically takes a considerable equity stake, diluting existing shareholders (usually the company’s founders). One corporate development consultant estimated the average VC equity stake to be approximately 70 percent of the company.50 Venture capitalists also take a hands-on approach to managing their investment, often taking at least one seat on the company’s board of directors and actively guiding the company’s management.

For some start-ups, this involvement is a feature, not a bug. If the company’s founders are inexperienced, either because of youth or general unfamiliarity with the ins and outs of running a company, they may welcome the guiding hand of VC’s well-seasoned executives. But other founders may prefer to keep a firm grip on the company’s reins and may therefore eschew VC interference in day-to-day operations and strategic planning.

In addition to the considerations above, venture capital may be inappropriate for a company due to the stage in its development. Because VC is generally looking for an exit in the near term—IPOs backed by venture funding in 2010 had received six years of support on average—these funds are typically interested in what might be called mature start-ups, those companies that are likely to have their biggest growth ahead of them but that have shown their mettle through initial growth and development of a healthy revenue stream.51 A very young company, one that has yet to launch its product or generate any revenue, would generally be too immature for VC investment.

Companies seeking very early stage investment, often called “seed money,” may turn to “angel” investors. Angels are individuals, or small groups of individuals, who invest smaller sums of money in brand new ventures. Where a VC might invest several million, an angel might invest $50,000 or $100,000, or even as little as $30,000. While all investors are looking for a return on investment, angels are generally also motived by an interest in helping new companies and fostering entrepreneurship. Angels themselves are frequently successful entrepreneurs who see this form of investing as a way to give back by identifying and supporting promising new entrepreneurs.

The form of an angel investment may also differ from the form of VC investment. Whereas VC firms almost always take an equity stake, an angel may take equity or debt, but often prefers convertible debt, which incorporates some of the most attractive features of each.52 The amount of guidance an angel provides will vary with the angel-company relationship. Some angels are interested in providing a great deal of expertise and guidance (which many companies are thrilled to have since such expertise may be extremely expensive if a company were to buy comparable services), while others are happy to take a more hands-off approach. Although angel investment can be a boon to new companies, it, like venture capital, can be difficult to secure. In 2010, 61,900 companies received angel investment, representing a little more than 12 percent of the total new businesses started that year, with an average investment of about $325,000.53 Angel investing has, however, been on the rise. In 2006, for example, the Bureau of Labor Statistics reported 667,341 new enterprises; but only 51,000 received angel funding, or about 7.6 percent.54

Angel investing has existed in some form throughout time. Beginning in the 1990s, however, angels began to form groups to seek investment opportunities. By forming a network, angels can more effectively connect with entrepreneurs seeking their help. With the advent of the Internet, some of these angel networks went online. To comply with the pre–JOBS Act ban on general solicitation, websites listing investment opportunities required investors to register and confirm their accredited investor status before viewing the offerings.

The result of the restriction on advertising has been to require a relationship-based approach to selling securities through private offerings. People must actually know people in order for the sales to work. This has resulted in great geographic concentration. Investors tend to invest in companies geographically close to them. The investors, brokers, and issuers have therefore all been grouped close together, historically in California, New York, and Boston.55 This means that innovations in other parts of the country may be starved of funds for no reason other than geographic accident. It also means that society at large has been deprived of new inventions and the benefits they bring only because of where the inventors lived.

Secondary Market for Securities Sold in Private Placements

The secondary market for securities sold through a private placement is also quite limited. The federal securities laws require not only that offerings be registered, but that securities themselves be registered as well, unless, as with offerings, they qualify for an exemption. Securities sold through a public offering are registered as part of the offering process. But securities bought through a private placement are not registered, and are therefore “restricted.” They cannot be resold unless the sale qualifies for an exemption.56 This restriction increases the price of capital raised through a private placement. A less liquid security will carry a higher premium to entice investors to effectively lock up their money.

One exemption from the registration requirement is for “transactions not involving an issuer, underwriter, or dealer.”57 This seems like an easy solution—wouldn’t most investors, trading amongst themselves, fall into this category? Unfortunately, no. The securities laws define “underwriter” so broadly that steering clear of the underwriter designation has made trading restricted securities very tricky to navigate. The Securities Act includes in its definition of an underwriter “any person who has purchased from an issuer with a view to … the distribution of any security[.]”58 The intent behind this interpretation is clear: if a security could be bought in a private placement and immediately resold to any investor, including any member of the public, the distinction between public and private offering would evaporate. But how to distinguish between the investor who bought a security for investment and one who purchased it with a “view to [its] distribution”?

Because this definition requires the SEC to peer into the mind of the investor to determine whether the investor bought the security with “a view to [its] distribution,” the law has developed to use certain behaviors as a proxy for determining what the investor’s intent may have been at the time of purchase. Most notably, the SEC has found the length of time between the initial purchase from the issuer and the sale in the secondary market to be relevant to the initial purchaser’s intent.59 To further remove uncertainty surrounding the underwriter designation, the SEC issued a rule in 1972 that creates a safe harbor for the resale of securities issued under the private placement exemption. Under Rule 144, an investor who holds a restricted security for six months if the company is a reporting company or a year for other companies may resell the security without being deemed an underwriter.

While Rule 144 provided some liquidity for restricted securities, a holding period of six months or a year is still a burden. Also, if the intent behind the underwriter designation for shorter holding periods was to prevent the security from immediate transfer into the hands of retail investors, it would seem that sales between accredited investors should be permitted. In 1990 the SEC issued Rule 144A. This rule allows restricted securities to be offered in the secondary market to “qualified institutional buyers,” or QIBs, without a holding period.60 Qualified institutional buyers are, in general, institutional investors that own and invest on a discretionary basis at least $100 million in securities, and dealers who own and invest on a discretionary basis at least $10 million in securities.

Note, however, that the rule requires restricted securities not only to be sold only to QIBs, but also to be offered only to QIBs. To understand the difficulty this restriction has imposed, it is important to understand what, exactly, “offer” means.

The definition of “offer” under federal securities law is notoriously broad. The Securities Act of 1933 states that “[t]he term … ‘offer’ shall include every attempt or offer to dispose of, or solicitation of an offer to buy, a security or interest in a security, for value.”61 This already broad definition has in turn been interpreted broadly by the SEC. A communication need not even expressly offer the securities for sale for it to be considered an offer. According to the SEC:

The publication of information and statements, and publicity efforts, generally, made in advance of a proposed financing, although not couched in terms of an express offer, may in fact contribute to conditioning the public mind or arousing public interest in the issuer or in the securities of an issuer in a manner which raises a serious question whether the publicity is not in fact part of the selling effort.62

Google famously had to delay its IPO because an interview its founders Larry Page and Sergey Brin gave to Playboy magazine arguably “contribut[ed] to conditioning the public mind or arousing public interest” in the IPO.

So, private placements, while vital to companies’ ability to access investment, nonetheless present some traps for the unwary. Moreover, many of the restrictions focusing on offer versus sale provide minimal benefit, if any, but have imposed substantial costs on issuers, investors, and on our economy as a whole, which benefits from companies’ ability to obtain the capital to grow.

JOBS Act Changes to Regulation D

Title II of the JOBS Act radically reforms the rules for solicitation of investors in both the primary and secondary markets for private placements. It directs the SEC to issue new regulations lifting the ban on general solicitation for Rule 506 offerings, specifically “to provide that the prohibition against general solicitation or general advertising … shall not apply to offers and sales of securities made pursuant to section 230.506, provided that all purchasers of the securities are accredited investors.”63 It also directs the SEC to change Rule 144A to allow offers to non-QIBs: “to provide that securities sold under such revised exemption may be offered to persons other than qualified institutional buyers, including by means of general solicitation or general advertising, provided that securities are sold only to persons that the seller … reasonably believe[s] is a qualified institutional buyer.”64 This means that private placements and securities sold in private placements can be offered, that is, advertised, anywhere. Television, billboards, banner ads on websites, cold calls, sky-writing airplanes flying over crowded beaches—it’s all okay. (Although, of course, these changes apply only to offers; actual sales remain restricted to accredited investors and QIBs.)

In September 2013, the SEC adopted final rules implementing these changes. Under these rules, the SEC created two versions of Rule 506 offerings: the traditional Rule 506 offering, which retains the prohibition on general solicitation and permits a limited number of non-accredited investors; and a new offering under Rule 506(c), which permits general solicitation but requires that issuers sell only to accredited investors.

Under the traditional Rule 506 offering (now named a “506(b)” offering to distinguish it from the new Rule 506 offering, which appears under Rule 506(c)), investors have typically self-certified their status, via questionnaire or other method. And an issuer, assuming it has a reasonable belief that the investor is indeed accredited, can rely on an investor’s assertion that he or she meets the income or net-worth requirements. Under Rule 506(c), however, issuers must take reasonable steps to verify accredited investor status, resulting in more work for the issuer. The SEC has provided a nonexclusive list of methods that an issuer might use to verify that an investor has the requisite income or net worth; these include reviewing tax documents, bank statements, a report from a nationwide consumer reporting agency, or obtaining written confirmation from an attorney, accountant, broker-dealer, or registered investment adviser.

Result of JOBS Act Changes to Regulation D

As the new rules implementing these changes went into effect only in late 2013, it is difficult to predict definitively the effect they will have on the private market. Although the rules’ implementation was much-touted in certain corners of the Internet,65 many small businesses remain unaware of the changes.66 Recent data suggest that fewer than 10 percent of Rule 506 offerings are conducted under the new 506(c).67 Additionally, even with the introduction of online platforms to connect investors with entrepreneurs, the investment process for many investors remains a personalized one. While many angel investors now use platforms to find entrepreneurs, online investment platforms take the place of introductions, not relationships. The process is not unlike online dating. The Internet enables people to search for and connect with others looking for a romantic relationship, but the relationship itself tends to take place offline, in real life. Similarly, angel investors can search for and connect with early stage companies online, but often prefer to meet and talk with the company’s founders face-to-face before making an investment.

The changes may, however, expand the population of private placement investors. Not every investor who qualifies as accredited will seek out an angel network to join. But such investors may be drawn in by advertising now permitted by the new rules. This may provide opportunities for those small businesses that can leverage existing relationships to raise funds, expanding the value of those connections.

Consider, for example, a luxury-good purveyor who has an established base of clients who are familiar with the product and with the company itself. The company may decide to seek investment from its customers, whom it knows include a number of individuals with the requisite income or assets and who may be interested in investing in this company, although they may not have sought out such investments in the past. Or consider other built-in investor audiences: alumni networks, local community members, subscribers to a niche-interest publication. Investing platform North Capital Private Securities recently announced that it will be using an online Rule 506(c) offering to raise $30 million to partially fund a giant Ferris wheel to be built on Staten Island.68 These investors will not be angels, in that they are unlikely to provide the mentorship that often accompanies an angel investment, but they may be interested in supporting a company affiliated with their personal interests.

There is also the possibility of developing Web-based platforms geared toward specific interests. The platform 1031 Crowdfunding, for example, permits investors to find one another to exchange investment real estate to take advantage of a provision in the tax code.69 Finally, although many existing angels may prefer to meet company executives in person before investing a sizeable sum, some may take advantage of the efficiencies of online investing to invest much smaller amounts—a few hundred dollars perhaps—in companies purely via online platforms. While $500 is not going to get any company off the ground on its own, multiple $500 investments could do the trick.

While the new 506(c) offering may provide greater opportunities for both investors and issuers, there are reasons a company may opt to select the traditional 506(b) offering instead. First, the issuer’s relationship with the investor can be somewhat different in a 506(c) offering than in a 506(b) offering. On the one hand, the issuer in a 506(c) offering will have access to documents and information about the investor’s financial situation that a 506(b) issuer would not have. Because 506(b) allows investors to self-certify that they are accredited, issuers would have no cause to review investors’ tax or financial documents, documents that must be reviewed by a 506(c) issuer looking to use the rule’s safe harbor. On the other hand, the issuer in a 506(c) offering ultimately may have less information about, and control over, the investors than a 506(b) issuer would have. Consider the method each uses to solicit investment. In the 506(c) offering, the issuer is likely to use the Internet or some other method of general solicitation (this is, after all, the raison d’ȇtre of the 506(c) offering). The issuer is using this method of attracting investment specifically because it allows the company to reach investors otherwise unknown to it. While this provides greater reach, it also means that the investing relationship will not be quite as close as the relationship between an issuer and investor who either already had a preexisting substantial relationship themselves or were introduced through a trusted intermediary. One of the advantages of being a privately-held company is the ability to control who owns you; choosing general solicitation as a means of finding investors risks ceding this control.

Second, the issuer in a 506(c) offering must choose what to disclose publicly as part of its general solicitation, navigating between the Scylla of exposing company secrets to a wide audience (including competitors) and the Charybdis of committing securities fraud. Any offering of securities, including one made pursuant to Rule 506(c), is subject to Rule 10b‑5, the federal securities laws’ catch-all fraud provision. This rule makes it illegal to:

Employ any device scheme or artifice to defraud, to make any untrue statement of a material fact or to omit to state a material fact necessary in order to make the statements made, in the light of the circumstances in which they were made, not misleading, or to engage in any act, practice, or course of business which operates or would operate as a fraud or deceit upon any person in connection with the purchase or sale of any security.70

While it requires some attention to detail, most issuers acting in good faith can refrain from making untrue statements of material facts. It is trickier to ensure that disclosures do not leave out necessary information, the omission of which may make them misleading. To see the difference, consider, for example, a manufacturing company with two factories. It would be plainly misleading to state that the company had three factories when it had only two. But what if the second factory was currently shut down due to a broken piece of machinery that would cost $1 million to replace? Now the company, if it discloses the existence of two factories (where clearly manufacturing capability is a material fact), must also disclose the fact that one is currently shut down and will require $1 million to fix so that its statements are not misleading.

The traditional 506(b) private placement does not require any specific disclosures if the offering is limited to accredited investors. But the investors typically receive a private placement memorandum (PPM), which includes all the information the issuers feel the investors would want to know before investing in the company. While the information can be quite sensitive, it is not made publicly available and is provided only to those eligible to invest in the company. As discussed in the context of the IPO on-ramp earlier, the ability to keep information secret from competitors is one of the great advantages of remaining a privately-held company.

It may be that issuers conducting a new 506(c) offering will choose to provide interested investors with a private placement memorandum. But it is unlikely that they will want to make it widely available. While any company conducting any kind of offering can fall afoul of Rule 10b‑5, it will be especially challenging for a company to provide sufficient information to entice investors through general solicitation while simultaneously ensuring the information is not misleading due to an omission.

As with Title I, the changes that Title II makes to the securities laws are relatively small—506(c) offerings are still available only to accredited investors, and securities sold through these offerings are still restricted. But they provide a flexibility that will enable new companies that might have otherwise been shut out of the market for reasons unrelated to the quality of their business models to access capital. And they allow investors new opportunities and options in allocating their funds and permit those outside the venture capital hot spots to influence the development of new products and services through investment. The 506(c) offering may appeal equally to an established company and to a start-up. Most important may be the company’s ability to convert existing relationships into investment or to appeal to an audience broader than what has traditionally been the source of early stage investment. While less glamorous than Title III, which creates the new crowdfunding exemption, Title II may result in a greater impact on capital access.

Policy Recommendations

The current definition of accredited investor is too limited. The best solution would be to do away with the accredited/non-accredited distinction entirely, and permit individuals to make their own decisions about how they want to spend their money. In the alternative, the accredited investor standard should be revised to ensure it reflects an investor’s actual ability to evaluate an investment. Wealth alone has little bearing on whether a person is well-informed, or even well-advised, on investment matters. Even if it did, using a fixed number with no reference to variances in cost of living gives preference to people living in certain parts of the country. It also favors age over other measures of experience. Under existing law, for example, a retired physician living in New York City might be able to invest in a start-up developing new mining technologies while a young mining engineer, who is much better informed about mining itself and about the industry in general, would be excluded.

The current method of calculation also excludes the primary residence. This recent change means that two people, each with say $2 million, would be treated differently if one chose to buy a $1.5 million house and invest the rest, while the other decided to rent a house and invest the whole $2 million. Each would have the same net worth, but the investment the first individual made in a house would not be considered in the same way that the second individual’s first $1.5 million investment would be considered.

The accredited investor calculation should be revised to again allow investors to include the value of the primary residence. There should be an additional method of qualifying as an accredited investor that allows an individual to demonstrate knowledge of basic finance and investing concepts. Finally, an individual should be able to invest in specific offerings upon a showing that the investor has knowledge of the issuer’s industry. A certain amount of work experience in that industry, a professional qualification, or a university-level degree in a field directly related to the issuer’s industry would be presumed to confer the relevant knowledge.

Title III: Investment Crowdfunding

Title III of the JOBS Act is by far the most ambitious of the act’s titles. While every other title simply tweaks elements of existing securities law, Title III, through a collection of interwoven exemptions, creates an entirely new kind of offering. Included in its exemptions are: an exemption for the offering from registration under Section 5 of the Securities Act of 1933 even though it is an offering to the public; an exemption for the company from registration under the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 even if the company would otherwise trigger the requirement that it register once it exceeds a certain number of shareholders of record; and exemption from registration as a broker-dealer for a new type of entity, the “funding portal.” The novelty of this title, and the genesis of this collection of exemptions, have created a number of challenges for the SEC in developing implementing regulations—challenges that, to a large extent, remain unresolved.

Origins of the Crowdfunding Exemption

The genesis of a crowdfunding exemption was not the SEC or even the financial industry. Its origins lie in the tech start-up world. In 2006, a new version of an old concept emerged, built on the Internet’s ability to radically reduce transaction costs across a wide geographic area. In its current incarnation, the concept is called “crowdfunding.” In general, crowdfunding refers to a means of raising funds by which small amounts are solicited from a large number of people.

The concept predates the Internet by hundreds of years. Long before the Internet was developed, people took up “subscriptions,” commitments to provide small amounts of money, to support public projects. Arguably the Statue of Liberty itself stands in New York Harbor thanks to a “crowdfunding” project.71 The Internet, however, has made this method easier to use, as reaching hundreds or even hundreds of thousands of people has become extremely cheap. A number of platforms have sprung up to facilitate the process. The most prominent is Kickstarter, followed closely by Indiegogo and Rockethub, among others. While these platforms tend to focus on actual projects, others such as GoFundMe allow individuals to seek funding for almost any purpose.72

In recent years, even before passage of the JOBS Act, a number of companies have turned to crowdfunding to obtain seed money. Because of existing securities regulation, however, companies are currently restricted in how they may use crowdfunding. They may solicit money from individuals, and they may provide benefits in exchange for that money—but not offer investment. Successful crowdfunding campaigns have included preferred status on a waitlist for the forthcoming product, a T‑shirt, or a handwritten letter of thanks from the company’s founder.73 They may not, however, offer a means by which investors can receive a return on investment.74 Given the nature of the rewards that companies may offer, the type of company that can currently use crowdfunding successfully is limited. Generally only a company with a certain level of charisma, either because it offers an innovative consumer product or because it exudes a coolness that people find attractive, will be successful in attracting this type of capital.

Frustrated by the inability to use crowdfunding more broadly, several entrepreneurs initiated a campaign to create an exemption to allow investment crowdfunding for small businesses.75 With the assistance of the Sustainable Economies Law Center, a nonprofit organization focused on developing local economies, they submitted a proposal for rulemaking to the SEC.76 Other entrepreneurs drafted proposed legislation, which they presented to lawmakers in late 2010.

This was when two very different worlds—the entrepreneurial world and the deeply complex world of SEC regulation—collided. Part of the appeal of crowdfunding is its grassroots nature. Early proponents of investment crowdfunding remarked on how ludicrous it was that such a simple form of investment was illegal.77 The investment crowdfunding concept was therefore intended to be extremely simple. The proposal submitted to the SEC envisioned a $100,000 cap on the offering and a $100 limit per investor. It suggested that issuers might be a local café looking to expand, a community garden, or a bookstore interested in adding a stage and public address system for small performances—all very small businesses whose owners may not have a high level of financial sophistication. Embedded in the concept was the idea that issuers could do a crowdfunded offering without the raft of legal and financial experts typically needed for even a small private offering, and certainly without the army of experts employed by the issuer planning an IPO.

How the Crowdfunding Exemption Will Work

Unfortunately, given the complexity of the federal and state securities laws and their attendant regulations, even a simple exemption for a very simple type of offering cannot ultimately be done simply. Although the exemption is entirely new, it is built into the same complex securities law framework that has existed for the last 80 years. The version of the exemption that was ultimately included in the JOBS Act will require, for most issuers, some professional guidance to navigate successfully. This may be its downfall. There is a $1 million cap on any offering using this exemption. Given the cost of professional assistance, any money raised under this exemption becomes extremely expensive and most issuers will likely find other exemptions more attractive.

The new exemption works as follows. A company may offer up to $1 million in securities, whether debt, equity, or some combination, to the general public over the course of one year without registering the offering with the SEC, provided the offering meets all of the requirements to qualify for the exemption. These include the following: the issuer may not be a public company and must be a U.S. entity. The issuer must provide certain information to the SEC, including the issuer’s name and address, the identities of its officers and directors, and a description of the issuer’s business plan. It must also disclose its financial condition, provide financial statements and information regarding its capital structure, and disclose how much it wants to raise, what it will do with the proceeds, and what the price of the securities will be. The issuer must meet its full funding goal for the raise to close; if it fails to meet its target by a set deadline, no sales occur.

After the offering closes, the issuer must comply with ongoing reporting requirements. It must make annual disclosures to the SEC and its investors regarding business operations, and must produce its financial statements.

The exemption also imposes certain restrictions on investors. Prospective investors must pass a financial literacy test, which must include an acknowledgment of the fact that the investor could lose the entire investment. The amount any one investor may invest in crowdfunding securities in one year is capped at an amount based on the individual’s annual income and net worth, but investment for any investor, regardless of wealth, is capped at $100,000 annually.

Finally, the offering must be made through either a registered broker or dealer, or through a new entity termed a “funding portal.” Under the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, any person “engaged in the business of effecting transactions in securities for the account of others,”78 or “engaged in the business of buying and selling securities” for that person’s own account79 is a broker or dealer and therefore must register with the SEC.80 Registration as a broker or dealer is an onerous process. It requires registration with the SEC itself and with the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA). While nominally a private entity, FINRA functions in a quasi-governmental role, writing and enforcing a number of rules for the financial services industry, the violation of which can result in loss of license and fines. Among FINRA’s rules for broker-dealers are that broker-dealers and their employees must pass certain examinations, written and administered by FINRA; that the broker-dealer must maintain established capital levels; and that the broker-dealer is subject to a fiduciary duty standard in certain transactions and relationships, exposing the broker-dealer to substantial litigation risk.

The JOBS Act provides an exemption from these requirements for persons “acting as an intermediary in a transaction involving the offer or sale of securities for the account of others”81 as long as those transactions are exclusively within the crowdfunding exemption. But the funding portal loses its designation—and therefore its exemption—if it provides investment advice; solicits purchases, sales, or offers for the securities on its platform; pays commissions for the sale of the securities it has listed; or holds or manages investor funds or securities.

This is not to say that, by virtue of being exempt from registration as brokers or dealers, funding portals are unregulated. In fact, Title III clearly intends for funding portals to act as gatekeepers for the crowdfunding industry. They must register with the SEC and with FINRA, provide investor education, ensure that investors do not exceed the individual investment cap, and protect confidential information. They are also given the task of ensuring that funds are not released to issuers until and unless they have reached their funding target.

Then there are the anti-fraud provisions, which apply both to funding portals and to issuers. Both are subject to the wide-ranging liability of Rule 10b‑5. Additionally, the JOBS Act includes a provision creating a new cause of action specific to crowdfunding offerings, imposing liability on the issuer for a material misstatement or omission of a required statement. Once again, the securities laws interpret a term so broadly as to create a number of regulatory hurdles. Although “issuer” would seem to apply only to the company actually issuing the securities, in fact the securities laws define issuer to include the company, its directors and partners, its principal executive, and its financial and accounting officers.

The definition of “issuer” also includes “any person who offers or sells the security in such offering.”82 The Supreme Court has construed the term “issuer” broadly enough that a funding portal arguably falls within the definition of “seller” in this context.83 Unlike Rule 10b‑5, which requires a finding of scienter, or an intent to defraud, the new provision in the JOBS Act requires no such intention; if there is a finding that there was a material misstatement or omission, liability attaches unless the seller can show that reasonable due diligence would not have uncovered the error. Of course, that does not mean that any misstatement will result in liability. The misstatement must be “material,” which, under the securities laws, means that there is “a substantial likelihood that the disclosure of the omitted fact would have been viewed by the reasonable investor as having significantly altered the ‘total mix’ of information made available.”84

The Final Rules

How this exemption will work in practice is yet to be seen. The exemption requires implementing regulations from the SEC and FINRA, and the SEC only just issued final rules in October 2015, which will become effective on May 16, 2016—several years after the JOBS Act directed the SEC to issue regulations.85

Neither the delay nor the exemption’s complexity is surprising. The concept of investment crowdfunding was met with considerable apprehension, by lawmakers and by some within the industry and academia, when first proposed.86 Securities regulation exists, in part, to protect investors. If portions of the rules are rolled back, one of two things must happen: either investors lose needed protection and are thereafter defrauded or otherwise unjustly parted from their wealth, or those portions of the rules were unnecessary and therefore many assumptions underlying the architecture of the securities laws are incorrect.

One of those assumptions is that any offering sold to the public must provide certain required disclosures. Under this assumption, the SEC must prescribe the disclosures because retail investors are not sophisticated enough to know what information they should request before investing. There is some validity to this assumption. Many retail investors may not know enough about corporate finance or governance to know what information exists, never mind which pieces of information they should consider before investing. The benefit of having the information provided through SEC-mandated disclosures is that every company’s filing will look similar, making it easy for the investor to compare disclosures across companies.

While it may be beneficial for some investors to have assistance in obtaining information about potential investments, it is not clear that all of the disclosures required for a public company would be valuable for a potential crowdfunding investor. Despite the talismanic properties sometimes attributed to this body of disclosures, it is unlikely that a crowdfunding investor looking to invest $100 or $1,000 would benefit from such a large volume of information.

Additionally, SEC-mandated disclosures are not the only way for an investor to obtain information. The nature and structure of crowdfunding encourages information-sharing and engagement. Some in the industry argue that there will be no fraud in crowdfunding because the “crowd”—that is, the online investing community—will quickly identify and report fraudsters.87 Such a blanket dismissal of the risk of fraud is naïve, as there is nearly always fraud where there is money to be made, but the ability of investors and potential investors to share information seamlessly online will likely check some illicit activity. The proposed rules include a specific provision allowing for communication through the funding portal, including communication between the issuer and investors.88 Moreover, the issuer’s ability not only to provide information to investors, but to interact and engage with them, offers a new means of responding to specific requests. An issuer need not anticipate all investors’ requests and satisfy them with one data dump. The disclosures can be an ongoing, interactive process.

As for the need for guidance in understanding what information is relevant to making an informed investment decision, the SEC is not the only source for such assistance. Private sector actors can provide help, too. For example, CrowdCheck (of which the author is a founder and owner) is a company founded specifically to help investors conduct the due diligence necessary to making an informed decision when investing in a crowdfunding offering.