Central bankers and mainstream monetary economists have become intrigued with the idea of reducing, or even entirely eliminating, hand-to-hand currency. Advocates of these proposals rely on two primary arguments. First, because cash is widely used in underground economic activities, they believe the elimination of large-denomination notes would help to significantly diminish criminal activities such as tax evasion, the illicit drug trade, illegal immigration, money laundering, human trafficking, bribery of government officials, and even possibly terrorism. They also often contend that suppressing such activities would have the additional advantage of increasing government tax revenue.

The second argument relates to monetary policy. Proponents maintain that future macroeconomic stability requires that central banks have the ability to impose negative interest rates, not only on bank reserves, but on the public’s money holdings as well, and this can be accomplished only by preventing the public from hoarding cash.

Yet the arguments for phasing out cash or confining it to small denomination bills are, when not entirely mistaken, extremely weak. The advocates bear the burden of proof for such an extensive reshaping of the monetary system, but they offer no genuine or comprehensive welfare analysis based on people’s subjective preferences. They ignore or significantly understate the clear benefits from much underground production. They cannot provide any good quantitative evidence about how much of the underground economy constitutes harmful criminal acts, nor to what extent predatory activity would actually be curtailed by phasing out cash. They cannot even demonstrate that there will be net revenue gains for governments.

With regard to macroeconomic stability, the proponents of restricting cash fail to grasp all the implications of negative interest rates, which would essentially entail a comprehensive tax on money holdings. Here again they are unable to make a convincing case that the policy is even needed, much less that it would work. Above all, these proposals entirely ignore any political-economy considerations and are far too optimistic about the overall benevolence and competence of governments. Ignored are the public-choice dynamics of the myriad regulations these proposals require. The advocates remain willing to rely entirely upon the foresightedness of policymakers, having apparently learned no cautionary lessons from the numerous and repeated policy failures of the past and around the world today. In short, they appreciably oversell any advantages to restricting cash and ignore or understate the severe disadvantages.

Introduction

Central bankers and mainstream monetary economists, both in the United States and abroad, have become intrigued with the idea of reducing, or even entirely eliminating, hand-to-hand currency. This idea was first put forward by Kenneth S. Rogoff in a 1998 article in Economic Policy.1 Rogoff, a former chief economist at the International Monetary Fund and now a professor of economics at Harvard University, has continued to argue the case in scholarly articles, in op-eds, and most extensively, in his 2016 book, The Curse of Cash.2 Other prominent economists who have embraced some version of the proposal include Charles Goodhart, formerly at the Bank of England and now at the London School of Economics; Lawrence H. Summers, former U.S. secretary of the treasury and president emeritus at Harvard University; Peter Bofinger, a member of the German Council of Economic Experts; and Willem Buiter, global chief economist for Citi.3 The Bank of England’s chief economist, Andrew G. Haldane, has also seriously explored the option, albeit without fully endorsing it.4 Already the scheme has been partly implemented in some countries, particularly Sweden, while the European Central Bank plans to phase out 500-euro notes by the end of 2018.

Because Rogoff stands out as having presented the most comprehensive and careful case for restricting hand-to-hand currency, the details of his scheme are worth attention. I will follow his terminology of confining the term “cash” exclusively to paper money. In developed countries, Rogoff would phase out, over a decade or more, all large-denomination notes: in the United States, for instance, first $100 and $50 bills and then $20 bills and perhaps $10 bills. For small transactions, he would leave in circulation smaller-denomination notes, although he considers eventually replacing even these with “equivalent-denomination coins of substantial weight” to make it “burdensome to carry around and conceal large amounts.” To put this in perspective, $1, $2, and $5 notes make up less than 2 percent of the value of U.S. notes, or a little more than 3 percent if we add in $10 bills.5 For less-developed countries, Rogoff concedes that it is far too soon to “contemplate phasing out their own currencies,” yet “there is a case for phasing out large notes.”6

The advocates of this or similar proposals rely on two primary arguments. First, because cash is widely used in underground economic activity, they believe the elimination of large-denomination notes would help to significantly diminish criminal activities such as tax evasion, the illicit drug trade, illegal immigration, money laundering, human trafficking, bribery of government officials, and possibly even terrorism. They also often contend that suppressing such activities would have the additional advantage of increasing government tax revenue.

The second argument relates to monetary policy. They maintain that future macroeconomic stability requires that central banks have the ability to impose negative interest rates, not only on bank reserves, but on the public’s money holdings as well, and this can be accomplished only by preventing the public from hoarding cash.

Not all who promote limits on cash adhere to both arguments. Summers, for instance, is exclusively concerned about “combatting criminal activity” and eschews “any desire to alter monetary policy or to create a cashless society,” whereas Buiter appears primarily interested in facilitating negative interest rates.7 But Rogoff, among others, wields the two arguments in tandem, and their combination has created a vocal constituency promoting the same goal.

Proposals for phasing out cash have attracted the support of certain business interests as well. These interests operate through a private-public organization known as the Better Than Cash Alliance (BTCA), which was created in 2012. The BTCA’s funding comes from government agencies, such as the United Nations Capital Development Fund and the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), as well as commercial enterprises, including Citi, Visa, and MasterCard. The BCTA lists as members 24 nation-states in the developing world and 21 international organizations. The BTCA claims it wants to eliminate cash in less-developed countries to expand financial inclusion for the world’s poor. However, it does not shy away from aggressive government measures that would compel people to abandon cash. For instance, one BTCA report advocates “measures to encourage or require government entities, private businesses, and individuals to shift away from cash, sometimes in the form of policies that disincentivize cash usage” (emphasis added).8

As we shall see, even at their most cautious and scholarly, the arguments for phasing out cash or confining it to small denominations are, when not entirely mistaken, extremely weak. The proponents fail to provide a credible case that countries doing so would enjoy benefits that exceeded costs, or even that their governments would reap net revenue gains. Nor are the advocates of negative interest rates able to demonstrate that such a policy is needed, much less that it would work. Finally, these proposals raise grave political-economy concerns that advocates hardly ever address or even recognize. In short, they appreciably oversell any advantages from restricting cash and ignore or understate the severe disadvantages.

The remainder of this policy analysis consists of four sections. The first will explore the costs and benefits of the underground economy: What is the underground economy’s size and composition, and how much overall use of cash does it account for? Will phasing out cash generate any significant revenue for the government or produce a net welfare gain for the economy? And how will suppression of the underground economy affect the poorer and disadvantaged? The second section discusses seigniorage: that is, government revenue from issuing cash. How much seigniorage will governments lose from phasing out cash, and why shouldn’t they allow the private issue of currency? What will be the effect on foreign users of U.S. dollars? The third section looks at negative interest rates as a tax on money. Are government-imposed negative interest rates needed? Would that policy be more effective than alternatives for achieving the same goal, and would it avoid additional downsides that would make negative rates risky or dangerous? The final section will take up the broader public-choice aspects of phasing out cash. Does the underground economy, in addition to its economic benefits, provide essential political safeguards for a free polity, and would the suppression of cash require or facilitate significant restrictions on liberty?

The Underground Economy: Costs and Benefits

The Role of Cash in the Underground Economy

Rogoff asserts that the “overall social benefits to phasing out currency are likely to outweigh the costs by a considerable margin.”9 But in order to demonstrate these net gains, one must do a genuine economic welfare analysis and consider the policy’s impact upon the well-being of all who are affected. For the moment, we will focus on the potential gains and losses for the United States, its residents, and other users of U.S. currency. As of the end of 2016, not counting currency held in bank vaults, there was roughly $4,200 in cash per person in the United States, 80 percent of it in $100 bills. Estimates of how much of total U.S. currency is held abroad vary between 45 and 60 percent.10 If most of the U.S. currency held abroad is in the form of $100 bills, then U.S. residents, on average, must be holding around 12 of them. Yet a 2014 study from the Boston Federal Reserve, based on surveys with admittedly small sample sizes, suggests that only 1 in 20 adult U.S. consumers holds $100 bills.11 So the obvious inference is that the bulk of these domestically held high-denomination bills must be lodged in the U.S. underground economy.

However, the evidence for this inference is not as reliable as it may seem at first. As Lawrence H. White has pointed out, “people who agree to answer survey questions have every incentive to under-report their holdings, whether acquired lawfully or otherwise. It stands to reason that ordinary citizens who hoard cash . . . are the very people who are least likely to divulge the true size of their hoards to strangers, no matter what assurances of anonymity they receive.”12 A 2017 study from the San Francisco Federal Reserve finds that “cash was the most, or second most, used payment instrument regardless of household income” (emphasis added) and that it is even used to make 8 percent of all payments of $100 or more.13 Although what exact denominations are used in these payments is unknown, such ongoing use of cash for these large transactions at least suggests that high-denomination bills may still provide vital and completely licit economic services. As for eliminating smaller denomination notes, cash still remains the dominant means of payment in the United States, accounting for 31 percent of all transactions by volume. A 2017 European Central Bank study finds that reliance on cash throughout the Eurozone is even more striking. Europeans, for instance, use cash to make 32 percent of payments of 100 euros or more.14

No one denies that a lot of cash circulates within underground economies, which are composed of both criminal activity and activity that is unreported but otherwise legal. But what should be emphasized at the outset is that however large that amount, whether for the United States or any other country, extensive use of cash in the underground economy cuts both ways in arguments about phasing out cash. A greater relative amount of cash within an economy can not only indicate a larger underground sector, but likewise implies that the economy is more heavily reliant on the use of cash, making any phase-out that much more traumatic. In addition, any benefits from suppressing cash depend on how much underground activity constitutes truly predatory criminal acts and how much is beneficial production that merely evades taxes or other regulations but nonetheless increases welfare.15 I am unaware of any detailed attempt by the opponents of cash to tease out these proportions.

Alleged Gains in Revenue and Welfare

Instead of undertaking a detailed welfare analysis, advocates of phasing out cash tend to tout potential revenue gains—often as their sole quantitative evidence. Rogoff, for instance, relies on Internal Revenue Service estimates of the unpaid U.S. taxes from legally earned but unreported income in 2006 and extrapolates forward to approximate a net tax gap of $500 billion in 2015. Assuming that half of those unpaid taxes derive from cash transactions, he deduces that the elimination of large-denomination notes could close the gap by at least 10 percent. Rogoff thus puts the potential gains to the national government at $50 billion annually (or less than 0.3 percent of GDP), along with approximately another $20 billion gain for state and local taxation. He points out that “this calculation does not take into account the efficiency costs of tax evasion.”16

Peter Sands, a senior fellow at Harvard’s Kennedy School, in a working paper written with student collaborators and entitled “Making It Harder for the Bad Guys: The Case for Eliminating High Denomination Notes,” also extols potential revenue gains. “Given the scale of cash-based tax evasion,” he writes, “you only have to assume a fairly modest impact on behavior to generate a substantial increment to tax revenues.” Yet Sands offers few hard estimates of how significant those gains would be. When he does, the estimates are more limited in scope than Rogoff’s and the projected gains are smaller. For instance, looking at only “under-reporting on non-farm proprietor income and under-reporting of self-employment tax” in the United States, Sands projects a revenue increase of $10 billion.17

Taxes do more than simply transfer funds from taxpayers to the government. They also discourage people from doing whatever is being taxed. If this inhibits otherwise productive activity, the tax will impose additional economic losses as well as generate tax revenue. Economists refer to these net losses as “deadweight loss,” because there are no offsetting gains to the government. Thus, the downside of these alleged revenue gains from restricting cash is the potential deadweight loss from taxing and discouraging underground economic production. A genuine analysis of economic welfare would have to give some weight to the social costs of forcing what is productive unreported activity from a marginal tax rate of zero into marginal rates as high as 30 to 40 percent.

Both Sands and Rogoff attempt to slip around this requirement by noting that tax evasion also distorts economic output. As Rogoff explains, “if taxes can be avoided more easily in cash-intensive businesses, then too much investment will go to them, compared to other business that have higher pre-tax returns.”18 In other words, more efficient investments are supplanted by less efficient ones, resulting in a deadweight loss. This is correct as far as it goes. But in order for it to be relevant to a welfare analysis of phasing out cash, either one of two conditions, or some combination of the two, must hold. First, any increase in government revenue must finance a genuine public good whose benefits must offset and exceed the increased deadweight loss from the heavier taxes. Second, the increased deadweight loss from taxing underground activity must be offset by decreased deadweight loss from existing taxes.

The second condition depends on Rogoff’s observation that “if the government is able to collect more revenue from tax evaders, it will be in a position to collect less taxes from everyone else.”19 In other words, the changes in the tax burden from eliminating large-denomination notes must be approximately revenue neutral—a strong assumption. Either of these conditions appears naively at odds with the politics of taxation.

The assumption of revenue neutrality ignores a host of other complications. As will be discussed below, phasing out cash will probably reduce the revenue that governments gain from issuing cash in the first place (seigniorage). As a result, it is not clear how large the tax gains would be, if there are any at all. Moreover, when government, through its central bank, increases the amount of cash in circulation, it causes the price level to be higher than it otherwise would have been. Any resulting inflation reduces the purchasing power of cash already in circulation and people’s real cash balances. This implicit tax on cash balances currently bears more heavily on underground, cash-intensive businesses. Phasing out cash not only changes both the level and type of taxation that these unreported, productive activities would pay, but also could subject them to burdensome regulation that imposes costs without generating revenue. A genuine welfare analysis should carefully assess all of these complications.

The Impact on the Vulnerable

Even if there are net government revenue gains from phasing out cash, the losses from eliminating more than just $100 bills would fall disproportionately on the poor. As one friend has written me, the advocates

should try waiting in line in Chinatown to buy vegetables while an old lady gropes in her purse for a few crumpled dollars and counts out her small change, or at Safeway where she painstakingly unfolds a coupon clipped from a free newspaper. This is how she budgets, she knows she can only spend what she has in her purse, when it is empty she stops spending. Tell her to go on line to check her balance, or top up her account and she will look at you as though you are from Mars. Take her cash away from her and you have locked her out of the modern economy, her local shops, her daily routine. Do that to her and millions like her, especially in the third world, and you will have idiotically vindicated the populists’ assertion that the elites are out of touch and clueless how the majority of mankind lives.20

Leaving in circulation small-denomination notes or coins will help somewhat, though not forever, as inflation steadily erodes their real value. Back in 1950, a $5 bill had purchasing power about equal to that of a $50 bill today, and even as recently as 1980, at the end of the Great Inflation, it had the purchasing power of about $15.

Rogoff, to his credit, recognizes the downside for the poor and advises that “any plan to drastically scale back the use of cash needs to provide heavily subsidized, basic debit card accounts for low-income individuals and perhaps eventually smartphones as well” (emphasis added). If the government takes the less costly option of merely providing 80 million free, basic electronic currency accounts for low-income individuals, he estimates that the public cost will be $32 billion per year.21 Of course, that represents another cost that will erode any gains in tax revenue and must be included in the overall welfare analysis.

Phasing out cash would particularly affect the poor who also happen to be illegal immigrants. Indeed, Rogoff champions his scheme as “far more humane and effective” than “building huge border fences.” But to the extent that phasing out cash does constrain the number of illegal immigrants, it represents additional deadweight loss for the U.S. economy. After all, employers pay wages high enough to attract illegal immigrants, in spite of all the other obstacles illegal immigrants face, and the resulting contribution to output increases the consumption of other Americans.22 Rogoff argues that “countries have a sovereign right to control their borders,” while also stipulating that he “strongly favor[s] allowing increased legal migration into advanced countries.”23 But this has little practical bearing on our welfare analysis: the only circumstance under which this particular consequence of phasing out cash might not generate an overall negative effect is if it brings about even greater cost reductions in the enforcement of immigration restrictions.

The Size and Composition of the Underground Economy

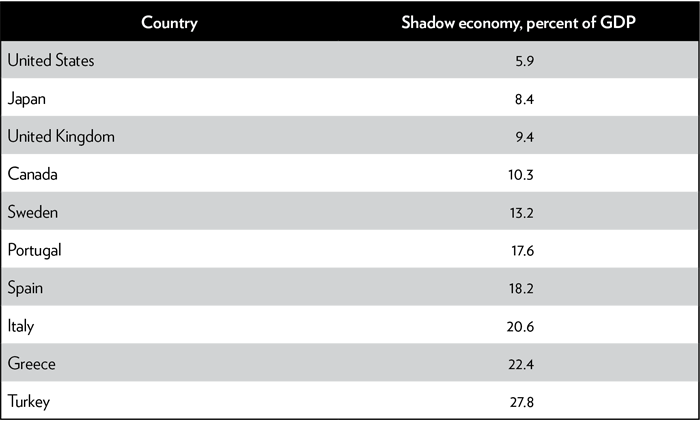

The relative size of the underground economy in other countries, whether rich or poor, is almost universally larger than in the United States. There is a vast literature on this topic using several techniques for estimating the size of the underground economy, but a widely cited pioneer in this field is Friedrich Schneider. His measures cover what he refers to as the “shadow economy,” which is limited to only unreported activity that is otherwise legal. Some of Schneider’s most recent size estimates, as a percentage of GDP in 2015, are shown in Table 1.24

Table 1

Estimated size of the shadow economy

The high percentages for some of these countries (including developed countries such as Greece, Italy, Spain, and Portugal, to say nothing of less-developed countries) suggest that many ordinary citizens earn their living in the underground sector. Schneider’s unweighted average for 28 European Union countries is 18.3 percent, which is generally conceded to stem from higher tax levels and more burdensome regulation in Europe.25

The obvious economic conclusion from these estimates is that the deadweight loss in Europe from inhibiting the shadow economy would therefore be considerably larger than in the United States. But Rogoff instead touts “the benefits of phasing out paper currency” in Europe “in terms of higher tax revenues.” In fact, he has gone so far as to concede that “the case for pushing back on wholesale cash use is weaker for the United States than for most other countries, first because perhaps 40 to 50 percent of all U.S. dollar bills are held abroad, and second because the U.S. is a relatively high tax-compliance economy thanks to its reliance on income taxes for government revenue.”26 This concession introduces an unrecognized tension in the case for phasing out cash: if doing so is less of a priority for the United States than for other countries with higher levels of tax evasion, then in essence restrictions on cash are least needed where they are least onerous to implement and most needed where their imposition would be premature or dangerous. After all, the most serious levels of tax evasion occur in less-developed countries, such as Brazil and India. Even in some relatively advanced economies, such as Greece and Italy, the underground economy exceeds 20 percent of GDP. Phasing out cash in an economy in which unreported transactions lift the economy’s total output by as much as one-fifth is clearly drastic, even if the transition is slow.

Bear in mind that Schneider’s estimates ostensibly include only underground activity that is unreported but otherwise legal. He attempts to exclude criminal activity. Yet governments frequently classify as crimes productive exchanges that enhance people’s well-being. This makes the dividing line between criminal and legal underground activity hazy. Thus, Schneider’s estimates include the output produced by illegal immigrants, while excluding that from the trade in illegal drugs. But here again, the only reason that drug cartels generate huge profits is that they supply products that consumers demand. An economist, despite paternalistic disapproval of such preferences, should include in a complete welfare analysis the lost consumer surplus from any further hindrance to serving those preferences. Indeed, Rogoff does mention legalization of marijuana as a simpler approach for at least that part of the illegal drug trade.27

With respect to crime that represents bona fide predatory acts, such as extortion, human trafficking, violence associated with the drug trade, and terrorism, any gains from phasing out currency are particularly difficult to quantify and establish. Almost all estimates of the scale of such crime include the drug trade broadly defined, rather than isolating the costs of predatory acts. For instance, a 2011 report from the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime approximated total global money laundering in 2009 arising from all crime (excluding tax evasion) at $700 billion, of which half was attributed to illegal drugs, whereas less than 5 percent ($31.6 billion) was attributed to human trafficking.28 And Schneider, in his most recent analysis of cross-border financial flows from crime, concludes that only half of that $31.6 billion associated with human trafficking involved actual cash rather than other means of money laundering, such as wire transfers, security deals, and shell corporations.29 Keep in mind also that these estimates encompass the entire world.

Schneider concludes that “a reduction of cash can reduce crime activities as transaction costs rise, but as the profits of crime activities are still very high, the reduction will be modest (10–20% at most!),” with the bulk of this reduction coming out of the drug trade.30 In his working paper, Sands devotes most of its 63 pages to detailing how such criminal enterprises—which he lumps together in a category he calls “financial crime”—can or might employ high-denomination notes. But when he gets to actual numbers, Sands concedes that there is scant empirical evidence: “it is impossible to be definitive about the scale of impact on tax evasion, financial crime and corruption.”31 Rogoff similarly relies upon anecdotal evidence to buttress his claim that eliminating cash would curtail such activities. As for corruption and bribery, he admits that these are really serious problems only in poorer countries—precisely where he also concedes that a premature elimination of cash would have devastating economic consequences. With regard to terrorism, Rogoff concludes that eliminating cash would have, at best, minor effects.32

Seigniorage: Government Revenue from Cash

Measuring Seigniorage

One major cost that opponents of cash take seriously is the lost government revenue from issuing cash—what economists refer to as seigniorage. Each dollar of currency put into circulation by the government’s central bank helps to finance government expenditures, either directly or indirectly. There are two ways of measuring the resulting revenue. They are referred to as monetary seigniorage and opportunity-cost seigniorage. Monetary seigniorage measures the government’s expenditure gain as the total value of new currency issued over a particular period of time. Opportunity-cost seigniorage measures the government’s gain as the ongoing interest the government would have had to pay if it had financed those same expenditures through borrowing from the public by issuing debt securities rather than through issuing currency.

In long-run equilibrium, these are just two ways of estimating the same seigniorage, since the present value of the future stream of interest that government does not have to pay should equal the total value of the cash issued. But to arrive at total lost seigniorage, one must employ both measures, because phasing out cash would both diminish future increases in currency and require the government to replace some existing currency with more government interest-bearing debt. Monetary seigniorage gives the best estimate of the expected lost revenue from future increases in currency, whereas opportunity-cost seigniorage tells us how much it would cost to eliminate existing currency.

Between 2006 and 2015, the federal government averaged 0.4 percent of GDP annually in monetary seigniorage from printing new notes and spending them. That comes to just under $70 billion in 2015. To phase out all existing currency by replacing it with interest-earning Treasury securities would increase the U.S. national debt by nearly 7.5 percent. Assuming a real interest rate of 2 percent on the additional debt, the lost opportunity-cost seigniorage would amount to $28 billion.33 Thus the combined annual cost of eliminating both existing and future U.S. currency would be $98 billion per year, or more than 0.5 percent of GDP. Notice that this already exceeds Rogoff’s projected minimum of $70 billion in total revenue gains to both the federal and state governments—which would, of course, have already been eroded by his estimate of a minimum of $32 billion to subsidize debit-card accounts for the poor.

Several factors could cause the calculation of lost seigniorage for the U.S. government to be either lower or higher than $98 billion. The real interest on government debt could be lower, as it has been since the financial crisis. It could be higher if, for whatever reason, market participants cease to view Treasury securities as riskless. If the future demand for new currency on the part of the public falls, then seigniorage would decline anyway, and therefore less of the loss could be attributed to phasing out cash. The estimated loss also does not include any seigniorage arising from the reserves that banks hold on deposits at the Fed and can easily be converted into vault cash.

The magnitude of seigniorage arising from bank reserves could change drastically in either direction depending on what happens to the banking system’s aggregate reserve ratio and the interest the Fed continues to pay on those reserves. But probably the most important potential mitigating factor is how much cash is ultimately phased out. If the U.S. government eliminates only $100 bills and continues to provide the remaining 20 percent of currency, lost seigniorage falls to $77 billion, or even less if the Fed replaces $100 bills with more small-denomination notes in response to public demand.34 On the other hand, Rogoff’s most drastic proposal—ultimately phasing out all denominations above $5, comprising 98 percent of the value of all cash—leaves little room for any increased substitution of small denominations to offset the lost seigniorage. In short, no matter how you play with these offsetting numbers from the increased taxes and lost seigniorage from phasing out cash, they do not seem to render significant net revenue gains.

True, some other developed countries, lacking a foreign demand for their currency, have much lower rates of seigniorage than the United States. According to Rogoff’s estimates, monetary seigniorage from future issues of cash (and ignoring the interest cost of eliminating existing cash) for Canada and the United Kingdom amounts to only 0.18 percent of GDP in both countries. Therefore, government losses in those countries if they phased out cash would be less severe than in the United States.35

But for other developed countries, rates of seigniorage are as high or higher than for the United States, either because of foreign demand or greater domestic currency usage. Whereas in the United States the ratio of currency in circulation to GDP in 2016 was only 7.4 percent, it was 10.1 percent in the Eurozone, 11.1 percent in Switzerland, and 18.6 percent in Japan. The resulting rates of monetary seigniorage as a percentage of GDP (again ignoring the opportunity cost of phasing out existing cash) are 0.55 percent for the Eurozone, 0.60 percent for Switzerland, and 0.40 percent for Japan.36 Eliminating only the 500-euro note could therefore cost as much as 17 billion euros annually in lost seigniorage. This is not surprising, given that a European Central Bank survey found that 32 percent of respondents usually pay with cash for transactions of 100 euros and above, as noted above. If Japan were to eliminate only its 10,000 yen note, which is worth about $90 and represents a remarkable 88 percent of the value of its cash in circulation, the government would lose about 19 trillion yen in seigniorage annually.37

International Users of U.S. Dollars

For the United States, one flip side of lost seigniorage would be the negative effect on those using the approximately 50 percent of dollars held abroad. Yet advocates of phasing out cash have so far ignored this effect on countries that have completely dollarized, using only U.S. dollars instead of a domestic currency (Panama, Ecuador, El Salvador, East Timor, the British Virgin Islands, the Caribbean Netherlands, Micronesia, and several small island countries in the Pacific), or partially dollarized (including Uruguay, Costa Rica, Honduras, Bermuda, the Bahamas, Iraq, Lebanon, Liberia, Cambodia, and Somalia, among others). The dollar once helped bring the Zimbabwe hyperinflation to an end, but it seems unlikely that the U.S. government would provide basic debit-card accounts or smartphones to poor foreigners who rely on dollars. Indeed, it is unclear how this could even be accomplished in less-developed countries lacking adequate banking sectors. This is another factor that has not been adequately considered by those who advocate phasing out cash. As Pierre Lemieux, in a critical review of Rogoff’s The Curse of Cash, succinctly puts it, “the economist venturing into normative matters would normally attach the same weight to a foreigner’s welfare as to a national’s.”38

Rogoff realizes that “some would argue that large U.S. notes are a powerful force for good in countries like Russia, where paper dollars give ordinary citizens refuge from corrupt government officials.” But he goes on to claim that “for every case where dollar or euro paper currency is facilitating a transaction that Americans might somehow judge morally desirable, there are probably many more cases where they would not, for example, human trafficking in young Russian and Ukrainian girls to France and the Middle East” (emphasis added). He therefore concludes that “foreign welfare should be thought of as a wash.”39 Rogoff does not, however, provide any quantitative evidence to back up this conclusion. And, in the absence of such evidence, we should take seriously the harm that could occur to those using dollars as a sanctuary from oppressive and corrupt governments if cash was phased out.

Given that we have only guesses based on anecdotes about alternative uses of dollars abroad, it certainly is appropriate to quote a contrasting view from a correspondent who has commented on this debate:

Based on my experience with overseas relatives, $100 bills are also favored by ordinary citizens seeking a refuge from their own country’s unstable currency. They have no use for smaller bills, as they don’t use dollars for ordinary transactions. Dollars, for them, are a way of protecting their savings from the vagaries of the local currency. They aren’t familiar with all the denominations of US currency and would not be confident that smaller bills were genuine but they know what a $100 bill looks like and are comfortable with it.40

Seigniorage itself arises, as pointed out above, from an implicit tax on people’s real cash balances, with an associated deadweight loss. Yet the fact that people continue to demand and use hand-to-hand currency, both domestically and abroad, demonstrates that it still brings net benefits. (For the United States, the only exception is pennies and nickels, which cost more to manufacture than their face value and therefore generate negative seigniorage.) After all, many alternatives to cash exist already—checks, debit cards, credit cards, Automated Clearing House transactions, mobile payment devices—and at the margin people are taking considerable advantage of them. In the future, entrepreneurs will undoubtedly come up with innovations and cost cuts that make these alternatives even more attractive. But to prematurely force people into digitized electronic payments by eliminating nearly all cash, rather than allowing this transition to proceed through a spontaneous market process, will produce further welfare losses.

The only theoretical objection to such a market transition would be the alleged existence of what economists call “network externalities.” White succinctly explains the basic argument:

Each individual sticks with cash so long as his trading partners do, and vice-versa. Cash is then the inferior of two alternative equilibria, to which the economy has been “locked in” by historical accident. Intervention can establish the digital-payments equilibrium that everyone agrees is better but has been blocked by the need for everyone to switch together.41

This is the implicit rationale of the BTCA in its advocacy of government compulsion to shift people in less-developed economies out of cash into digitized payment mechanisms. USAID administrator Rajiv Shah asserted in 2012: “It took the credit card industry fifty years to gain traction in the United States. But this slow rate of adoption teaches us that collective action is necessary to drive transformational change.” Yet as White asks, “On what basis does Shah know that the experienced rate of adoption was too slow?”42 Shah would need to know that the benefits of a government-financed and coerced transition would have exceeded the costs. But rather than offering any numbers or studies, he just assumes net gains. In fact, the validity of the negative externality justification for phasing out cash has never been explicitly demonstrated.43

Moreover, as unconvincing as this theoretical justification is for poor countries heavily reliant on cash, it is not actually applicable to developed countries with highly sophisticated banking and clearing systems.44 Rogoff predicts that “the use of cash in the U.S. in legal tax-compliant transactions will be well under 5 percent ten years from now and probably only 1–2 percent twenty years from now, and that is assuming no change in government policy on cash” (emphasis added).45 Consider the case of Sweden, the country that has moved closest to a cashless economy. Although the government has phased out the 500- and 1,000-krona notes (worth about $60 and $120, respectively), which became invalid by the end of June 2018, a close look reveals that Sweden’s shift toward digital payments has also been driven extensively by a market response to public preferences. Sweden’s central bank is contemplating the issue of its own electronic currency, but a publicly available e-krona would be a redundancy since private providers already fulfill this demand where it is truly cost effective.46

Summers and Sands offer a particularly revealing riposte to those opposed to getting rid of $100 bills. They ask if “liberty was constrained by the US decision in the 1960s to stop printing $1,000 bills or to stop issuing bearer bonds? Surely it is not a government’s obligation to provide every means of payment or store of value that someone might choose to use.” The obvious difference, as Sands elsewhere admits, is that in the case of the $1,000 note (along with $500, $5,000, and $10,000 notes, all last printed in 1945 and then withdrawn from circulation beginning in 1969) “the amounts outstanding were already so small by the time they were formally eliminated, as to make [the] impact negligible.”47 Summers and Sands, in contrast, want to eliminate the $100 notes precisely because people use a lot of them, because Summers and Sands consider those users to be the wrong kind of people.

The Case for Privately Issued Currency

A more fundamental issue is why governments monopolize the issue of currency at all. Why not permit banks to issue their own currency, as they did in the past? This was advocated by none other than Milton Friedman in one of his later writings.48

Indeed, a full and complete welfare analysis might arrive at the opposite conclusion of those who want to phase out cash: there may be too little currency in circulation rather than too much. After all, government already biases people’s decision against use of paper currency with its monopoly, which generates seigniorage well above costs. This creates an unrecognized distortion inefficiently encouraging alternatives to hand-to-hand currency.49 White has pointed out that “we can withdraw all the denominations that the Federal Reserve and the Treasury issue so long as we let competing private financial institutions issue dollar-redeemable notes and token coins in any denominations they wish.” Scottish banks still issue their own banknotes, with a 100 percent reserve requirement. These banknotes are not legal tender in England or even Scotland, but neither are Bank of England notes in Scotland, and yet the quantity of Scottish banknotes circulating as of 2006 amounted to 2.8 billion pounds. Kurt Schuler has discovered that, within the United States, Congress has already inadvertently repealed the legal restrictions on private banknotes. In all likelihood, federal authorities would come down hard on any bank that tried to take advantage of this unintended legal loophole, and the private minting of coins is still prohibited. Moreover, debit cards have made bank deposits nearly as easy to spend as banknotes once were. Yet if economists opposed to cash were more willing to promote such an enhancement of monetary freedom rather than further restrict it, then as White states, “we will have a market test and not mere hand-waving regarding which denominations are worth having in the eyes of their users.”50

Negative Interest Rates as a Tax on Money

The second main argument for phasing out currency is that it would facilitate imposition of negative interest rates. The idea that a negative return on money might sometimes be desirable is not entirely new. It dates back at least to the work of the German economist Silvio Gesell in the 1890s and was flirted with during the Great Depression by Irving Fisher and John Maynard Keynes.51 In its current incarnation, the potential need for imposing negative interest rates is grounded in New Keynesian macroeconomic theory, which assigns to monetary policy a major role in preventing or dampening business cycles.

The reasoning is as follows: When an economy sinks into recession, with its fall in output and rise in unemployment, the central bank should alleviate the downturn by stimulating the economy’s aggregate demand for goods and services. It can do so by using its monetary tools to lower interest rates. Normally, all this requires is an expansionary monetary policy in which new money that is injected into the economy, along with the concomitant fall in interest rates, drives up spending. But if interest rates are already extremely low, the public and the banks, rather than spending any newly created money, will tend to hold it and allow their cash balances to accumulate. In economic jargon, the demand for money can become highly “elastic.” This problem is alternately termed the “zero lower bound” or a “liquidity trap,” and it allegedly constrains the ability of central banks to use traditional monetary policy, with its short-term effect on interest rates, to bring about a rapid economic recovery.

Central banks can already charge a negative interest rate on the reserves that commercial banks and other financial institutions hold as deposits at the central bank. The central banks of Denmark, Switzerland, Sweden, the Eurozone, and Japan have started to do so. The practice, in turn, can put pressure on private banks to charge negative rates on their own depositors. If the monetary authorities push negative rates down too far, however, the public can just flee into cash, with its zero nominal return. Banks can also do the same thing by replacing their deposits at the central bank with vault cash. Elimination of cash would close off this way of avoiding negative rates, making negative rates truly comprehensive and effective and thereby spurring increased spending.

The term “negative interest rates” actually obscures somewhat the nature of what is contemplated. Reserve requirements on banks used to be common, but several central banks today—although not yet the Federal Reserve—have abandoned them. They have done this in part as a response to the observation of economists that required reserves are an indirect tax on banks, which makes the banks hold more non-interest-earning assets than they otherwise would. So, another way of thinking about negative rates on reserves is as a direct, rather than indirect, tax on banks. If the negative rates can be extended to the general public, they in effect become a direct tax on the public’s cash balances, or more precisely, their monetary balances, since most cash would be gone. In fact, Rogoff frequently describes negative rates as a tax on money. The one exemption from this near-universal levy that he considers is for “accounts up to a certain amount (say, $1,000–$2,000).”52

If negative interest rates were to be imposed long enough, governments could generate revenue and partly offset the seigniorage lost from restricting cash.53 Inflation, of course, already imposes an implicit tax on real cash balances. Negative rates thus reverse the causal chain of traditional monetary theory, which focuses on the money stock. To the extent monetary expansion increases spending, it causes higher inflation with its implicit tax on money. Negative interest rates, in contrast, would directly tax money in order to cause increased spending with higher inflation. I explore the importance of this difference below.

The growing scholarly literature on the zero bound has reached no consensus about whether it is a pressing problem for standard monetary policy. We therefore need to address four questions about directly taxing money with negative rates. First, is the policy needed? Second, will the policy work? Third, is the policy more effective than alternatives for achieving the same goal? And fourth, does the policy avoid additional downsides that would make it risky or dangerous?

Let us see why affirmative answers for all four questions are largely unconvincing.

Is the policy needed?

Are negative interest rates needed? If we take a long look back over the last three quarters of a century, even the most enthusiastic proponents of negative rates can identify only three cases when negative rates arguably might have helped: the Great Depression, Japan’s Lost Decade, and the financial crisis of 2008. Although the persistence of low interest rates, low inflation, and slow growth after the recent crisis still raise the specter of the zero lower bound, there is little agreement among economists about the causes and seriousness of those prolonged trends. Among competing explanations, Lawrence Summers’s secular stagnation thesis does leave room for a more aggressive monetary policy, although Summers has rejected the abolition of cash as a potential remedy.54 But those who contend that slow growth results from declining innovation, including Tyler Cowen and Robert Gordon, give monetary policy almost no role.55 And Steve Hanke, applying the concept of regime uncertainty, suggests the possibility that activist monetary policy might even be part of the problem.56

A more germane issue is whether the zero bound constrains monetary policy at all. Allegedly, very low interest rates make money demand so elastic that any increases in the money stock are locked up in people’s cash hoards and banks’ reserves, rather than being spent. Yet Milton Friedman and Anna Schwartz, in their classic Monetary History of the United States, demonstrated that during the Great Depression, when massive banking panics caused the total money supply to collapse, the Federal Reserve made no effort to counteract the decline by increasing that segment of money it directly controlled: the monetary base. The surviving banks did increase their reserves, but the major reason for the fall in the broader money supply was the widespread disappearance of bank deposits.57 Ben Bernanke, in 2000 and again in 2002, when discussing Japan’s experience with low interest rates, pointed out that by merely increasing the monetary base, a central bank could ultimately buy up everything in the entire economy—except that before it manages to do so, people will certainly start spending and drive up inflation. This scenario is sometimes referred to as a “helicopter drop,” from a thought experiment first suggested by Friedman, and it supposedly failed to work when the Federal Reserve, under Bernanke’s leadership, engaged in quantitative easing.58

A close examination of the Fed’s quantitative easing, however, discloses that Bernanke’s policies never involved authentic monetary expansion. Because of concerns about inflation (as Bernanke divulges in his memoirs), the Fed sterilized its bailouts of the financial system during the early phase of the financial crisis, selling off Treasury securities to offset any effect on the monetary base. When the Fed finally orchestrated its large-scale asset purchases in October 2008, it did so mainly by borrowing the funds in one of three primary ways: through a special supplementary financing account from the Treasury; through short-term, collateralized loans from financial institutions known as reverse repos; and most important, through paying interest on bank reserves for the first time. When the Fed thus borrows money and then reinjects it back into the economy, it is not in any real sense creating new money.59

Interest-earning reserves, in particular, encouraged banks to raise their reserve ratios rather than expand their loans to the private sector. This newly implemented monetary tool (acting as a substitute for minimum reserve requirements) therefore ended up lowering the money multiplier at the same time the Fed was increasing the monetary base. Looked at from another angle, the Fed became the preferred destination for a lot of bank lending, borrowing from the banks by paying them interest on their reserves in order to purchase other financial assets. Almost the entire explosion of the monetary base constituted this kind of de facto borrowing. In this way, the later phase of Bernanke’s policies transformed the Fed into a giant government intermediary that merely reallocates credit. Such financial intermediation can have no more effect on the broader monetary aggregates than can the pure intermediation of Fannie Mae or Freddie Mac. In short, quantitative easing hardly entailed massive money printing, as so many have characterized it.60

Other central banks that dabbled in so-called quantitative easing did so later than the Fed, and with similar impediments. The European Central Bank (ECB), being particularly concerned about inflation at the outset of the financial crisis in late 2007 and early 2008, initially conducted an even tighter monetary policy than the Fed. Only with the European debt crisis did the ECB in 2010 begin its first round of quantitative easing, at a time when it was still continuing its long-standing policy of paying interest on reserves.61 When the ECB initiated its second round of quantitative easing in January 2015, it was applying negative rates, but only on excess reserves. And it did not drop the positive interest on its required reserves to zero until March 2016.62 By then, the newly imposed Liquidity Coverage Ratio of the Basel III international banking regulatory framework had already gone into effect. The Liquidity Coverage Ratio is more complicated than reserve requirements, but it, too, can induce banks to hold more reserves than they otherwise would.63 In sum, it is far from true that, after the financial crisis, genuine monetary expansion was tried and failed. Instead, it was not actually tried.

Will the policy work?

Will negative interest rates work? As Stephen Williamson, formerly at the St. Louis Fed, points out in a review of Rogoff’s The Curse of Cash, the results of early trials with negative rates have not been promising, noting “the central banks that have experimented with negative nominal interest rates . . . appear to have produced very low (and sometimes negative) inflation.”64 But I agree with Rogoff; these early experiments have been too few and too tentative to provide definitive conclusions. They have been almost entirely confined to negative rates on bank reserves, and usually only excess bank reserves. The Bank of Japan even grandfathered in excess reserves acquired before the new policy, paying banks a positive return of 0.1 percent on those reserves. To determine how well negative rates might work, we must take up more theoretical issues.

The advocates of negative interest rates believe that, with a few minor adjustments, “cutting interest rates in negative territory (e.g., from −1.0% to −1.5%) works pretty much the same way as interest rate cuts in positive territory (e.g., from 1.5% to 1.0%).”65 But on the contrary, this symmetry clearly does not hold at the operational level. To the extent that central banks affect interest rates in positive territory, they do so with open-market operations or their equivalent, resulting in changes to the monetary base and bank reserves. But the very reason the zero bound is considered a problem is that these tools presumably do not work as well, if at all, in negative territory. Negative rates, in contrast, can be imposed and managed simply by taxing bank reserves. They therefore require no concomitant open-market purchases or sales and therefore place no automatic market constraints on how far down the monetary authorities push negative rates.

At first glance, this operational asymmetry would seem to make taxing money more powerful than open-market operations. Yet the operational asymmetry between the two leads to an asymmetry in how they bring about changes in spending. Unlike open-market operations that affect the supplyof money, negative interest rates affect the demand for money. They are designed to increase money’s velocity by motivating people to spend more rapidly. In contrast to constant money growth, which can generate sustained inflation, any increase in velocity induced by plunging into negative rates should have only a level effect, generating at best a one-shot rise in the price level. Admittedly, if the rate at which money balances are taxed continually rises, the central bank could, in theory, produce sustained inflation. But none of the advocates of taxing money appear to have in mind a policy that continually pushes negative rates lower and lower.

This difference suggests that negative rates should have weaker effects than monetary growth has. Rogoff expects that negative rates might need to be in place for a year or two for them to achieve even this limited effect on spending.66 A sustained velocity boost does occur during hyperinflations, but that is only because the government, starved for tax revenue, continually increases the rate of monetary growth to maintain the real level of its seigniorage after each jump in velocity. Once monetary growth is under control, the velocity boost always ceases. To be truly effective at increasing the rate of inflation, rather than just an unsustained spending bulge, a negative-rate policy would likewise require accompanying monetary expansion. But if monetary expansion is doing the real work anyway, why is a tax on money needed at all?

This leads to the most plausible argument that advocates of negative interest rates can make. By acknowledging that, yes, monetary expansion does the real work, they can contend that negative rates will simply make issuing money through open-market operations more effective. In other words, any increase in the monetary base required to stimulate spending will be more modest with negative interest rates than without them. While this is likely true, the crucial question is how much more modest. The evidence so far from the experience with negative rates on bank reserves has hardly been encouraging. Even if it had been, that result would ironically undermine the urgency of taxing money generally. The question thus remains: Why couple negative rates on bank reserves with such an encompassing and extreme policy as eliminating cash when the effectiveness of negative rates is unproven? If the primary concern is that banks would pile up reserves in the form of vault cash, there are far less encompassing options for discouraging that, such as limiting or imposing negative rates on vault cash.

There are other perspectives from which to challenge the efficacy of negative interest rates. Williamson offers a critique based on the “neo-Fisherian” approach of John Cochrane. Although an expansionary monetary policy is generally thought to push interest rates down in the short run, to the extent that the policy increases the rate of inflation, it does the opposite in the long run, increasing nominal interest rates. This long-run impact is known as the Fisher effect. As people expect higher inflation, they drive nominal rates up to keep real interest rates roughly constant. Williamson believes that “central bankers have the sign wrong.” Invoking the Fisher effect, he contends that a negative “nominal interest rate reduces inflation, even in the short run” (emphasis added).67 I believe that the neo-Fisherians get the causality backwards—running from the nominal interest rate to the rate of inflation rather than the other way—except in the case of taxing money holdings, in which the negative rate can indeed be entirely divorced from what is happening to the money stock.

The confusions about the symmetry between positive and negative interest-rate policies, as well as the misconceptions about quantitative easing mentioned above, stem from the current focus on interest rates as the sole target and indicator of central bank policy. As George Selgin has incisively expressed it, “It seems to me that in insisting that monetary policy is about regulating, not money, but interest rates, economists and monetary authorities have managed to obscure its true nature, making it appear both more potent and more mysterious than it is in fact.”68 However one ultimately resolves these captivating theoretical debates about the channels through which monetary policy actually works, they certainly call into question whether taxing money will achieve the macroeconomic goals prophesized for it.

Is the policy more effective than alternatives?

Are negative interest rates more effective than alternatives for achieving the same goal? We noted above, when explaining the apparent impotence of quantitative easing, that so long as the central bank expands the monetary base with newly created money rather than recycling funds through financial intermediation, it can eventually hit any inflation target it chooses. Unfortunately, when Bernanke invoked Friedman’s helicopter drop, he coupled the projected monetary expansion with either a tax cut or some government expenditure to distribute the money. Subsequently, many economists have accepted a requirement for some coordination with fiscal policy.69 But this assumption is simply wrong—and a misinterpretation of Friedman, who, in his classic chapter on “The Optimum Quantity of Money,” never linked his helicopter drop with any fiscal initiative—nor is there any reason that it has to be linked.70 Although we can imagine circumstances in which the desired expansion would exceed the supply of government securities available for open-market purchases, central banks can purchase, and have purchased, other financial assets or made other types of loans. The Fed has already purchased mortgage-backed securities, and other central banks have extended their acquisitions still more broadly, some even purchasing equities. Although far from ideal, such limited, and hopefully temporary, expansion of central-bank involvement in credit markets would be less invasive than an untested, all-embracing tax on money.71

A host of other ways of dealing with the zero bound have been proposed. Among them are communicating future central-bank policy in what is called “forward guidance” (another policy that, like negative rates, attempts to influence the demand rather than the stock of money); a higher inflation target; pure fiscal policy; Martin Feldstein’s plan to stimulate spending with a value-added tax; Silvio Gessel’s stamp tax on money; and dual-currency schemes that set up a managed exchange rate between cash and central-bank liabilities. These proposals have spawned a vast literature that need not detain us. For those interested, Rogoff systematically reviews these alternatives in The Curse of Cash, where he persuasively argues that none are simultaneously attractive and effective.72 Forward guidance, for instance, is unobjectionable, but by itself is not potent. In the final analysis, neither phasing out cash nor the other assorted alternatives that Rogoff dismisses would be both as simple to implement and as powerful in their effect as a straightforward monetary injection.

Does the policy avoid additional downsides?

Do negative interest rates avoid any additional downsides that would make them risky or dangerous? Although some people have raised concerns about the effect of negative rates on lending generally and on the viability of such financial institutions as banks, pension funds, and money market funds, these concerns mostly derive from negative rates imposed only on bank reserves, with cash still widely available.73 Far more complex is a world with all but the smallest denominations of currency eliminated and most money held as deposits at financial institutions or in some other electronic form. Presumably, in this world the tax on money would impinge on nearly all lenders and borrowers across the board, except those with small exempt accounts or those who are holding the remaining cash and coins. James McAndrews, formerly of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, foresees such ubiquitous complications as “redesigning debt securities; in some cases, redesigning financial institutions; adopting new social conventions for the timeliness of repayment of debt and payment of taxes; and adapting existing financial institutions for the calculation and payment of interest, the transfer and valuation of debt securities, and many other operations.”74

No one to my knowledge has systematically worked out how financial intermediation would function in this world, either in the short term or long run. It is even unclear whether nominal interest rates generally would turn negative. In the range of positive rates, lenders and borrowers respond to inflation’s implicit tax on cash balances by raising market-determined nominal rates. What is to prevent the same outcome from an explicit tax on money that is more akin to a near-universal service fee for deposit balances? Indeed, since the tax on money could be entirely independent of what is happening to the total money stock, it is conceivable that the central bank simultaneously orchestrates a monetary expansion that adds inflation’s implicit tax on cash balances on top of the explicit tax.75 This is a broad topic too daunting for this policy analysis, and outside of a few stray observations about how certain financial practices or institutions might adapt, very little literature has taken up the challenge.76

Negative interest rates in a cashless economy end up giving an unelected regulatory body discretionary power to tax money. All things considered, it is hard to be consoled by Rogoff’s almost self-contradictory complacency: “One’s gut instinct is that shifting to electronic currency will be a fairly smooth process, though it is simply not possible to definitely rule out the possibility that it will upset social conventions and expectations and lead to an outcome that is quite different than planned. This is the kind of ‘known unknown’ that government must plan for in making a transition.”77 Such reliance on government planning to resolve any unexpected difficulties brings us to our next subject.

The Political Economy of a War on Cash

Let us grant for a moment that the phasing out of all but small-denomination notes would accomplish what proponents claim: a marked reduction in crime, particularly bona fide predatory acts. Would it still be desirable? Not necessarily. We must consider whether that benefit offsets the harm to those who use cash for perfectly legitimate or benign reasons. We have already seen above that no one has quantitatively estimated the welfare loss to these users of cash. But there are further political-economy considerations that go beyond a strict cost–benefit analysis. Even when gains appear to be greater than losses, we should still hesitate about policies that punish or severely inconvenience the perfectly innocent.

Lemieux trenchantly points out: “Criminals are probably more likely than blameless citizens to invoke the Fifth Amendment against self-incrimination, or the Fourth Amendment against ‘unreasonable search and seizures.’ . . . But that is not a valid reason to abolish these constitutional rights.” These are necessary institutional constraints on state power, which not only protect the innocent but proscribe barriers that protect a free society more generally. And as Lemieux goes on to argue, the underground economy itself is another such constraint: “As regulation increases, more people—consumers, entrepreneurs, unfashionable minorities—move to the underground economy. Thus, government cannot regulate past a certain point.”78 Cash, in other words, enables people not only to escape harmful or misguided government intrusions, but also, in an indirect but effective way, to express their political concerns. As Frédéric Bastiat put it, “The safest way to make laws respected is to make them respectable.”79

Indeed, one could argue that the underground economy is often a more effective check on government abuses than voting itself. Voting encounters well established free-rider problems, fostering rational ignorance about political choices, all of which is amplified by confronting voters with, at best, a packaged bundle of usually unrelated policies. The underground economy, in contrast, allows citizens to focus their grievances on particular government interventions that they understand from firsthand experience. And the fact that the risk associated with their illegal or unreported transactions imposes a real cost dramatically demonstrates their genuine preferences, in stark contrast to pulling a lever or checking a box in a voting booth, which is virtually costless and inconsequential on an individual basis. Would alcohol prohibition in the United States have been repealed without widespread evasion by countless Americans? Would the United States be belatedly moving to marijuana legalization without the escape mechanism of the underground economy?

Harold Demsetz recognizes this “equilibrating process” fostered by the underground economy. He describes it as a system of internal checks and balances in which “current developments seem to be making underground sectors more important.”80 Obviously none of these considerations excuse human trafficking and other forms of violence or brutality that are also within the underground economy. But as noted above, those in favor of restricting cash offer no more than emotionally charged impressions about the magnitude of these acts compared to harmless or beneficial uses of cash. One should be very cautious about drastic government impositions that indiscriminately impinge on almost the entire population, no matter how deplorable the outrages they are intended to curb. Careful consideration should be given to alternative legal remedies that do not cast their web so widely.

Perhaps no issue illustrates these public-choice concerns more strikingly than the threat to financial privacy. Willem H. Buiter and Ebrahim Rahbari casually shrug off this cost, stating that it “has to be seen against the cost that the anonymity of currency presents to society. Even though hard evidence is hard to come by . . . [i]n our view, the net benefit to society from giving up the anonymity of currency holdings is likely to be positive” (emphasis added).81 We can overlook the problems inherent in making policy recommendations based on purely subjective speculations rather than concrete data. We can also ignore the obvious failure, even on a strict cost-benefit basis, to factor in the possibility of increased cybercrime.82 What is most troubling here is the lack of concern Buiter and Rahbari show for the huge quantity of personal financial information that cash’s abolition would make readily available to political authorities. Increased government surveillance constitutes an institutional danger for any free society. We should therefore be very wary of schemes that enhance state intrusion into the remaining spheres of anonymity, despite whatever advantages these spheres may give criminals.

Rogoff’s treatment of the effect on privacy is at least more nuanced and sensitive than that of Buiter and Rahbari.83 Nonetheless, consider the battery of ancillary coercive regulations that Rogoff thinks might be vital to ensure the success of his proposal. In addition to aggressive inducements to get people to turn in their cash (expiration dates for large notes, a maximum allowable size for cash payments, and charges on large deposits of small bills), his supplemental interventions include restricting anonymous cryptocurrency transactions to small transactions; “pull[ing] the plug on money market funds, which in the current environment remain a regulatory end-around”; lowering cash limits on anti-money-laundering regulations; preventing casinos from money laundering of euros; discouraging the use of prepaid cards for transactions involving large sums of money; and banning “large-scale currency storage” or imposing taxes on storage over a certain amount.84

If this barrage of interventions proves insufficient, Rogoff is certain that the government will be “vigilant about playing Whac-a-mole as alternative transaction media come into being” in order to make any alternative currencies impossible for financial institutions to accept and difficult for ordinary retail establishments to use. He predicts that “[t]o the extent that new approaches to financial transactions are developed to evade government efforts to root out their sources, they will be met with a stiff hand.” After all, “it is hard to stay on top of the government indefinitely in a game where the latter can keep adjusting the rules until it wins.” Rather than considering this government capacity a chilling concern, Rogoff enthusiastically embraces it.85

Several governments have engaged in what Canadian economics blogger J. P. Koning has called “aggressive demonetizations.” These are compulsory currency swaps, designed to rein in the underground economy by forcing tax evaders, money launderers, and others holding large sums of cash to either face government scrutiny or find their cash hordes stranded.86 Although not intended to eliminate large-denomination notes permanently, aggressive demonetizations offer instructive lessons about the pitfalls of eliminating cash. The most noteworthy case occurred when Prime Minister Narendra Modi of India announced on November 8, 2016, that the country’s two highest denomination notes (the 500 rupee and the 1,000 rupee, worth about $7.50 and $15, respectively) would cease to be legal tender at midnight. People were given slightly less than two months to exchange these notes, with restrictions, for new ones. Modi’s decree applied to 86 percent of the value of cash in circulation, and even introduced a new higher-denomination, 2,000-rupee note. But after Indians had to queue up for hours to receive the new notes, which were in short supply, and after the poor in particular experienced chaotic economic disruption, even the Indian government’s annual economic survey had to euphemistically concede that, in the short term, the experiment entailed “inconvenience and hardship.”87

More recently, even the most enthusiastic academic supporters of India’s currency swap have been forced to concede that it has probably “failed in achieving its primary goal,” in the words of Jagdish Bhagwati of Columbia University and his former students, Vivek Dehejia and Pravin Krishna. That goal was to penalize tax evaders, bribe takers, criminals, and terrorists, all of whom were assumed to be holding large hoards of old notes, which they would be afraid to exchange for fear of attracting government attention. This would also have provided seigniorage to the government, which would have been able to replace the unreturned notes with new issues of currency. Yet the Reserve Bank of India announced in September 2017 that 99 percent of the discontinued notes had been returned, eliminating the projected significant loss for holders of this alleged “black money.” Admitted holders of black money also had the option of converting their notes into deposits at a 50 percent tax, but that, too, has brought the government only trivial amounts of revenue. In short, Bhagwati, Dehejia, and Krishna have been forced to admit that “there is scant evidence that the policy had much if any impact on counterfeiting or terror finance.” On top of that, the former head of the Reserve Bank of India has concluded that the demonetization caused a noticeable fall in GDP growth.88

Aggressive demonetizations that were still more disruptive include Saddam Hussein’s 1993 recall of the Swiss dinar in Iraq, the North Korean won swap of 1999, and the Burmese kyat swap of 1985.89 Not to be outdone, Venezuela’s President Nicolás Maduro announced on December 11, 2016, that the 100-bolívar note, accounting for 77 percent of the country’s cash, would cease to be legal tender within 72 hours and would eventually be replaced by new notes of higher denomination. But this was clearly going to be such a serious blow to an economy already reeling from hyperinflation that the Venezuelan government repeatedly postponed the currency exchange and now appears resigned to never fully implementing it.90 These experiences, despite differing from plans to phase out cash in developed countries, should serve as a warning about potential government mismanagement and high-handedness. Nonetheless, several opponents of cash initially praised the goals behind India’s approach, predicting that, despite these short-run costs, the long-run benefits may prove worthwhile.91

The United States has already experienced the unfortunate consequences of two crusades to stamp out behavior considered by some to be illicit: alcohol prohibition and the ongoing war on drugs. These crusades have shared some of the same justifications that are made for phasing out cash. And just as the war on drugs has extended outside the borders of the United States, inflicting untold damage, advocates hope the elimination of hand-to-hand currency will become an international campaign as well. What guarantees do we have that this war on cash will not have results similar to those of these other crusades? When commenters have raised these objections, they are often dismissed as alarmists. But this dismissal is belied by the enormous range of discretionary powers the opponents of cash are cavalierly willing to grant to the state.

Conclusion

In the final analysis, it is the advocates of restricting hand-to-hand currency who bear the burden of proof for such an extensive reshaping of the monetary system, no matter how cautiously or slowly implemented and no matter whether all cash is eliminated or just large-denomination notes. Yet they have failed to demonstrate any bountiful gains from their proposals. They offer no genuine and comprehensive welfare analysis based on people’s subjective preferences. They ignore or significantly understate the clear benefits from much underground production. They cannot provide any good quantitative evidence about how much of the underground economy constitutes harmful criminal acts, nor to what extent predatory activity would actually be curtailed by phasing out cash. They cannot even show that there will be net revenue gains for governments. And their attempts to prove that cash is less efficient than electronic alternatives violate some of the basic precepts of welfare analysis.

With regard to macroeconomic stability, the proponents of restricting cash fail to grasp all the implications of the fact that negative interest rates would essentially entail a comprehensive tax on money holdings. Here again they are unable to make a convincing case that the policy is even needed, much less that it would work. Simply put, the problem of the zero lower bound vanishes once one thinks about monetary policy in terms of money rather than interest rates. In short, none of the arguments favoring restrictions on cash withstand close scrutiny.

Above all, the proposals to reduce or eliminate cash entirely ignore any political-economy considerations. Advocates are far more optimistic than is justified about the overall benevolence and competence of governments, particularly in developed countries, and unreflectively adopt what Demsetz has characterized as the nirvana approach to public policy.92 Their analysis thereby ignores the public-choice dynamics of the myriad regulations their proposals require, and they remain blissfully willing to rely entirely upon the farsightedness of policymakers, having apparently learned no cautionary lessons from the numerous policy failures of the past and around the world today.

Notes

Acknowledgements: I have received helpful comments and suggestions from David R. Henderson and George Selgin, but any remaining errors are my own.

1. Kenneth S. Rogoff, “Blessing or Curse? Foreign and Underground Demand for Euro Notes,” Economic Policy 26 (April 1998): 263–303, https://scholar.harvard.edu/files/rogoff/files/ep_1998.pdf; and Sylvia Nasar, “Crime’s Newest Cash of Choice,” New York Times, April 26, 1998, http://www.nytimes.com/1998/04/26/weekinreview/ideas-trends-crime-s-newest-cash-of-choice.html.