To combat the 2007-09 recession, the Federal Reserve implemented the Large Scale Asset Purchase program, more commonly known as quantitative easing (QE). The Fed intended to reduce the yields on certain long-term assets in the hope that this would spill over into the wider financial markets and so reduce other interest rates. According to the Fed, lower interest rates would cause investment and consumer spending to increase, thereby boosting output and employment.

This view of QE rests on shaky theoretical foundations. It requires us to accept an understanding of the term structure of interest rates that has been widely discredited in the economic literature and to make several implausible assumptions about the behavior of investors. The theory underlying the program is also difficult to justify empirically; in fact, there is virtually no credible evidence that QE led to persistent reductions in long-term yields via the channels identified by the Fed. The fact that QE was not accompanied by any substantial increase in bank lending further undermines the possibility that it stimulated economic activity.

Quantitative easing did have unintended consequences, however. Income was redistributed away from people on fixed incomes and toward better-off investors, while pension funds were forced to hold securities with greater default risk. Other problems may yet materialize: the distorted markets and excessive risk-taking encouraged by QE could lead to renewed economic instability, and the huge increase in the monetary base that QE entailed could cause inflation if the Fed loses control of excess bank reserves.

Had QE occurred earlier and focused on increasing the overall supply of credit, the financial crisis of 2007-08 and the subsequent recession might have been less severe. Any rise in inflation expectations could have been avoided by the Fed announcing that QE was temporary and would be reversed as soon as financial markets and the economy stabilized. However, the Fed was slow to respond to the developing crisis, and its exclusive focus on the interest rate channel of monetary policy was misguided. Ultimately, QE did little good and likely sowed the seeds for future economic problems.

Introduction

At its October 29, 2014, meeting, the Federal Reserve System’s Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) officially ended its Large Scale Asset Purchase (LSAP) program, more commonly known as quantitative easing (QE). Before that program unofficially began, on November 25, 2008, the Fed held just $490 billion worth of securities, all of which were Treasury obligations. By the program’s end, its holdings had risen to $4.3 trillion, comprising $2.5 trillion in Treasuries and $1.8 trillion in mortgage-backed securities (MBS). The program also more than doubled the average maturity of the Fed’s portfolio, raising it from about 5 years to more than 10 years.

The Fed had hoped the program would reduce longer-term yields. It held that spending on capital goods and consumer durables depends on interest rates; lower interest rates supposedly would cause investment and consumer spending to increase. That increase, in turn, would boost output and increase employment. This is how monetary policy is intended to work via the so-called “interest rate channel.”

This theory raises several important questions:

- Did QE actually work as intended?

- Did it have any noteworthy, unintended consequences?

- Can and should the Fed continue to conduct monetary policy with a large balance sheet?

- What challenges must the Fed meet in order to return to a more conventional balance sheet?

In this Policy Analysis, I offer answers to those and related questions.

Before QE: Sterilized Lending

To understand how and why QE began, one must first consider the Fed’s pre-QE responses to the subprime crisis. That crisis is generally considered to have begun on August 9, 2007, when the French bank and financial services company BNP Paribus suspended redemption of three of its investment funds. The Fed’s initial response to BNP’s announcement was anemic; for over a week it took no action at all. Then, on August 17, 2007, the Board of Governors lowered the Fed’s primary lending rate by 50 basis points — half a percent — while increasing its maximum loan term to 30 days, renewable by the borrower.

Another month passed before the FOMC made its own policy move. On September 18, the FOMC reduced its federal funds rate target by 50 basis points, to 4.75 percent. By April 30, 2008, a series of further reductions left the target at just 2 percent, where it remained until Lehman Brothers’ bankruptcy announcement on September 15, 2008.

In the meantime, the Board created several new emergency lending facilities. The first and most important of these, the Term Auction Facility (TAF), was announced on December 12, 2007.1 The TAF supplied funds to banks through a competitive auction. On the same day, the FOMC authorized temporary swap lines with the European Central Bank and the Swiss National Bank. That is, the Fed agreed to swap dollars for the dollar-equivalent amount of foreign currency.

In all, from the start of the crisis until Lehman Brothers’ failure, the Fed made loans to banks and others totaling more than $300 billion. According to then Fed chairman Ben Bernanke, these loans were intended “to short-circuit a possible downward spiral in financing markets.“2 However, the Fed “sterilized” this lending by selling an equal amount of government securities, thereby avoiding any increase in the total size of its balance sheet, and hence, in either total bank reserves or the monetary base.

In other words, rather than boosting the overall availability of credit or overall liquidity, the Fed merely shifted the existing supply of credit from the general market to a select group of firms. As I’ve noted elsewhere,3 by taking this step the Fed abandoned its long-standing policy of concerning itself only with the overall supply of credit, while leaving the allocation of credit to the private market.4 Indeed, the Fed conducted open market operations using short-term Treasury debt, rather than long-term Treasury debt or other public and private securities that the Federal Reserve Act allowed it to purchase, out of a desire to interfere with credit allocation as little as possible.

In announcing the TAF, the Board of Governors stated that “by allowing the Federal Reserve to inject term funds through a broader range of counterparties and against a broader range of collateral than open market operations,” it would “promote the efficient dissemination of liquidity when the unsecured interbank markets are under stress.“5 But just how sterilized lending could achieve this outcome was unclear even to some Board members.

At the January 29–30, 2008, FOMC meeting, St. Louis Federal Reserve President William Poole, who was aware that the TAF lending was being sterilized, observed that instead of changing “marginal” lending conditions, the TAF merely served to increase participating banks’ earnings.6 That is, banks were able to obtain funds through the TAF at a lower interest rate than they would have been able to obtain in the market. Poole’s remark prompted Richmond Federal Reserve President Jeffrey Lacker to ask whether TAF lending was, in fact, completely sterilized, what its distributional effects were, and how the Committee was supposed to determine whether it achieved its proclaimed objectives. In answer, New York Federal Reserve President William C. Dudley acknowledged that TAF lending was indeed completely sterilized. Furthermore, he conceded that he found it “hard to believe” that sterilized TAF lending could have resulted in any substantial increase in liquidity “in the system as a whole” because it was sterilized. Finally, Dudley admitted that it was essentially impossible to evaluate the TAF’s success, although he observed that the program didn’t appear to have “caused any great harm.“7 Boston Federal Reserve President Eric C. Rosengren, meanwhile, noted that the institutions that took part in the TAF were “overwhelmingly supportive.“8

Poole remained understandably skeptical. He replied:

We should not be surprised that banks like the TAF. It increases the bank’s profits because of the difference between the funding costs. The issue is whether the TAF improves the way the markets are functioning, not whether it’s feeding profits into the banks and whether they happen to like it.9

The discussion ended without any serious resolution of the question concerning how any amount of sterilized lending could possibly “short-circuit a possible downward spiral in financing markets” or otherwise promote the efficient dissemination of liquidity in the interbank market.10 That banks were using the TAF — and liked it — was deemed sufficient proof of its effectiveness.

Why was the Fed’s emergency lending completely sterilized? Oddly enough, that question never came up at any FOMC meeting. The evident reason, however, is that had the lending not been sterilized, the FOMC would have found it difficult, if not impossible, to continue to conduct monetary policy by targeting the federal funds rate (the interest rate at which depository institutions lend to one another excess reserves held at the Federal Reserve). Had the Fed’s lending not been sterilized, bank reserves would have increased by about $300 billion. Such a large increase in the supply of reserves would have driven the funds rate below the FOMC’s target. That is, in fact, what happened following Lehman Brothers’ bankruptcy, when the Fed, although still wedded to its former rate target, finally let its balance sheet grow.11 Prior to Lehman Brothers’ collapse, however, the FOMC did not entertain the possibility of providing additional liquidity (credit) in an effort to mitigate the liquidity crisis rather than sticking to a particular target for the federal funds rate.

That the Fed’s sterilized lending program had little positive effect is evidenced by the fact that the financial crisis intensified. This raises a now-obvious question: Instead of merely reallocating credit, should the Fed have resorted to QE sooner, and might it have contained the crisis by doing so?12

The Fed was aware of the market’s need for additional credit long before Lehman Brothers’ failure. In their much-celebrated Monetary History of the United States, Milton Friedman and Anna Schwartz connected substantial reductions in the nominal quantity of money and credit to correspondingly large declines in economic activity, and declared it the Fed’s duty to act quickly to prevent such reductions by expanding the monetary base.13 Immediately following the stock market crash of 1929, for example, the Federal Reserve Bank of New York increased the monetary base by a combination of open market purchases and liberal discount-window lending. Friedman and Schwartz called those actions “timely and appropriate.” However, the Fed soon reversed course, allowing both the monetary base and the money supply to decline significantly between September 1929 and October 1930. Subsequently the Fed expanded the monetary base again, but not nearly enough to compensate for sharp increases in public cash withdrawals and banks’ excess reserve holdings. To avert panic and prevent the broad money stock from collapsing, the Fed needed to increase the monetary base, and hence the total size of its balance sheet, far more aggressively. It failed to do so and the Great Depression ensued.

Ben Bernanke and other FOMC members were well aware of Friedman and Schwartz’s arguments. Bernanke had famously concluded a speech he gave in honor of Friedman’s 90th birthday by declaring: “I would like to say to Milton and Anna: Regarding the Great Depression. You’re right, we did it. We’re very sorry. But thanks to you, we won’t do it again.“14

But “it” is, in fact, precisely what the Fed did during the months leading up to Lehman Brothers’ failure. Instead of expanding its balance sheet to combat and prevent an incipient collapse of credit, the Fed resolved to keep it, and the monetary base, unchanged. And although its decision to do so may have been defensible (even on Friedman and Schwartz’s own terms) for the weeks immediately following the BNP Paribus crisis, it was no longer so by the end of 2007, let alone by March 14, 2008, when the Fed judged the overall state of the credit market sufficiently bad to warrant its taking on $29 billion in toxic assets for the sake of rescuing Bear Stearns. Yet more crucial months would pass before Lehman Brothers collapsed and the Fed finally allowed its balance sheet to grow.

Rather than heed Friedman and Schwartz’s advice to expand the Fed’s balance sheet, the FOMC was so wedded to its federal-funds-rate targeting procedure that it engaged in policies that even its members judged to be of doubtful efficacy and that ran contrary to the Fed’s longstanding practice of not engaging in credit allocation. As a consequence, the Fed lost a crucial opportunity to combat a collapse in credit before that collapse took on epic proportions following Lehman Brothers’ failure. Even then, the FOMC remained obstinately committed to its “no expansion” policy for some days following the decision to let Lehman Brothers fail.

Enter Quantitative Easing

Why did the FOMC finally allow the monetary base to grow? The answer is that it did so because after Lehman Brothers’ bankruptcy announcement it found itself lending on a scale that it could no longer sterilize. Quantitative easing thus began not as the culmination of an intense discussion about the relative efficacy of sterilized lending and alternative approaches to managing the crisis, but as an unplanned and unavoidable consequence of the fact that the Fed found itself making loans and purchasing assets in amounts that greatly exceeded the value of its Treasury holdings.

The Fed’s limited ability to sterilize its emergency lending came up at an FOMC meeting held the day after Lehman Brothers’ announcement. Bernanke worried that, if the Fed proved unable to sterilize its loans to the European Central Bank and other central banks, those loans would increase banks’ excess reserves and thereby further lower the federal funds rate. Bernanke suggested that the FOMC might nonetheless maintain its federal funds rate target using a new instrument of control: interest payments on bank reserves. If the foreign central banks drew extensively on their credit lines, he noted, “it would begin to affect some of these balance sheet constraint concerns that we have. I think that is not an entirely separate issue, but it is certainly one that we are looking at in terms of trying to get interest on reserves and those other kinds of measures.“15 Bernanke’s stand explains the Fed’s otherwise perplexing decision to begin rewarding banks for holding excess reserves on October 6, 2008 — that is, in the middle of a severe credit crunch, and just shy of three years ahead of the originally scheduled date for the introduction of this new monetary control instrument.

One other step was also taken to avoid expanding the supplies of money and credit. At the October 28–29, 2008, FOMC meeting, Dudley revealed that, in its determination to keep the supply of reserves from increasing, the Fed had taken the extraordinary step of offsetting additions to the supply of reserves “by having the Treasury issue supplemental financing program [SFP] bills and placing the proceeds on our balance sheet.” Unlike other Fed liabilities, Treasury deposits at the Fed are not part of the monetary base. Hence, SFP bills allowed the Fed to expand its balance sheet without expanding that base and, hence, without increasing the total supply of credit in the market. Dudley warned, however, that “the capacity to continue to drain reserves via SFP bills was unlikely to be a long-term solution because the Treasury would ultimately be constrained by the debt limit ceiling.“16 In fact, in spite of the new program, the monetary base increased by about $390 billion between the week ending September 10 and the week ending October 29.17

Although, strictly speaking, QE effectively began as soon as the Fed allowed its balance sheet to grow, during this initial, unofficial phase, the FOMC continued to treat monetary policy as a matter of setting a target federal funds rate. It did so in spite of the fact that the chosen target was no longer achievable. In the course of the previously mentioned FOMC meeting, Kansas City Federal Reserve President Thomas Hoenig anticipated the eventual transition to official QE policy:

I look at all of the things we have done over the last month, and the ramping up of the liquidity facilities has really exceeded even our ability to sterilize. So we have had, in effect, a funds rate that is well below our target. We have excess reserves in that period that were over $280 billion when they are normally $2 billion, and that was before we added more swap lines and more liquidity into the market. Frankly, I think we are at a point now where the liquidity mechanisms that we’re trying to use, not our interest rate targeting, are really our monetary policy. As we go forward, perhaps we need to think about how we are going to conduct monetary policy under a quantitative easing environment (emphasis added).18

The FOMC’s obsession with its federal-funds-rate operating procedure appeared to be out of touch with reality. For example, at the October 28–29 meeting, Chairman Bernanke recommended a 50-basis-point reduction in the Committee’s target rate, from 1.5 percent to 1.0 percent, suggesting “that it will be at least moderately beneficial both in terms of psychology and in terms of reducing the cost of funding and giving some additional support to funding markets.“19 He appeared oblivious to the fact that the actual federal funds rate had averaged just 82 basis points during the two preceding weeks, and that it had fallen to just 67 basis points the day before he made his proposal. Yet Hoenig opposed Bernanke’s proposal in favor of keeping the target at 1.5 percent. The reason for his opposition is not clear. Perhaps he was trying to make it more evident to his fellow FOMC participants that interest-rate targeting was dead. In any event, all of the voting members supported Bernanke’s recommendation.

The Fed’s new target rate was nevertheless just as meaningless as the former one had been. Between the October FOMC meeting and that of December 15–16, the funds rate averaged just 33 basis points, and was never above 62 basis points. Moreover, it averaged just 13 basis points during the nine days prior to the December meeting. At that meeting the FOMC decided to set, not a specific rate target, but a 0 to 25 basis points rate-target range.20 Bernanke was, in fact, on the verge of giving up on rate targeting altogether. He began the discussion by noting:

We are at this point moving away from the standard interest rate targeting approach and, of necessity, moving toward new approaches. Obviously, these are very deep and difficult issues that we are going to have to address collectively today and tomorrow. I want to say that, although we are certainly moving in a new direction and the outlines of that new direction are not yet clear, this is a work in progress. The discussion we’re having today is a beginning. It’s not a conclusion. Everyone can rest assured that this conversation is going to continue for additional meetings, and today we’re not going to be setting in stone an approach that will be used indefinitely (emphasis added).21

Bernanke was, however, reluctant to abandon funds-rate targeting altogether, noting that, although interest payments on reserves weren’t doing the trick, “we should continue to work to improve our control of the effective funds rate.… We should not give up on that.“22

The FOMC meeting transcripts for this period reveal a confused, if not bewildered, monetary policymaking body. The Fed was forced to expand the monetary base to provide banks and the financial market generally with much-needed credit (liquidity). However, because it had not thought about alternative approaches to conducting monetary policy during a financial crisis, the Committee continued to operate as if its funds-rate operating procedure was relevant. It embraced QE only when the funds rate went to zero and it could no longer keep up the fiction of targeting the funds rate.

Now the FOMC faced a new challenge: deciding how QE was supposed to work.

Quantitative Easing Theory: Federal Open Market Committee Discussions

A correct assessment of the success of QE depends on a correct understanding of how it was supposed to work. Given the way in which the FOMC stumbled into QE, it is hardly surprising that theoretical explanations of the policy evolved over time, with the justifications for QE taking shape in the course of the FOMC’s deliberations. Because transcripts of FOMC meetings are only available through 2009, Chairman Bernanke’s speeches and Federal Reserve staff papers are also used here to determine how QE was supposed to promote recovery.

The matter of precisely how the FOMC might conduct monetary policy without targeting the federal funds rate was first broached at the same October 2008 FOMC meeting at which Hoenig anticipated an official retreat from rate targeting. The main topics of discussion were how QE would work, whether the Fed should depart from its historical practice of purchasing only Treasuries, and, if it did so, what other assets it should purchase.

Although several views were offered concerning how QE worked, nearly all appealed to the so-called “interest rate channel” perspective on monetary policy. According to Bernanke, quantitative easing was “a way to bring down returns on assets and create stimulus even if the policy rate is down to zero.“23 Precisely how QE was supposed to bring down long-term yields was a matter of considerable disagreement.

The discussion of QE resumed at the December 15–16, 2008, FOMC meeting. The staff made a presentation of alternative ways the FOMC might conduct monetary policy “whether or not the Committee chooses to cut its target rate to zero.“24 Bernanke discussed two approaches the Fed would rely upon. First, it would make policy more effective through its communications (this was referred to as “forward guidance”). Second, it would stimulate the economy “by use of the balance sheet” — that is, by acquiring assets without reference to the funds target. He suggested that while the latter alternative resembled Japan’s “quantitative easing” during the 1990s, it was not the same thing. The theory behind Japan’s quantitative easing, he said,

was that providing enormous amounts of very cheap liquidity to banks…would encourage them to lend and that lending, in turn, would increase the broader measures of the money supply, which in turn would raise prices and stimulate asset prices, and so on, and that would suffice to stimulate the economy.… I think that the verdict on [Japan’s] quantitative easing is fairly negative. It didn’t seem to have a great deal of effect, mostly because banks would not lend out the reserves that they were holding. The one thing that it did seem to do was affect expectations of policy rates because everyone understood it would take some time to unwind the quantitative easing. Therefore, that pushed out into the future the increase in the policy rate.25

“What we’re doing,” Bernanke insisted, “is fundamentally different from the Japanese approach.“26 Unlike the Bank of Japan in the 1990s, the Fed would focus on the asset side of its balance sheet. The intent was not simply to enhance bank liquidity and to thereby encourage growth of the money stock. Such liquidity was, according to Bernanke, merely a byproduct of the Fed’s turn to unsterilized lending. The Fed’s goal was to reduce yields on particular long-term assets. The Fed’s unsterilized lending, like the sterilized lending that preceded it, was aimed not at enhancing the aggregate supply of credit available to the market, but at allocating credit to specific segments of the market that the Fed deemed most “credit constrained.” Unlike sterilized lending, U.S.-style QE would increase the supply of reserves at banks, but this would not increase the overall supply of credit, or the supply of money, so long as banks held new reserves as excess reserves. The Fed would employ its new tool of interest on reserves to assure this outcome.

Janet Yellen, who was then the president of the San Francisco Federal Reserve and now is the Reserve Board chair, echoed Bernanke’s opinion that Japanese-style QE had no effect on banks’ behavior or asset prices. She noted that, while the quantity of money affects the price level in the long run, “most evidence suggests that variations in the base have only insignificant economic effects in the short or medium term under liquidity trap conditions” — that is, when nominal interest rates are already at the zero lower bound and cannot be pushed lower by further injections of cash into the banking system.27

Yellen also raised the topic of the Fed’s acquiring assets other than short-term Treasury securities. Specifically, she suggested that the Fed should purchase large quantities of MBS “to boost activity in the mortgage and housing markets.” She further supported a policy of lending and asset purchases where “each credit facility program and asset purchase decision is judged on its own merits, according to whether it improves the availability of credit or lowers its cost, thus stimulating the economy.“28

Then Fed Board vice chairman Donald Kohn also supported a policy of aggressive credit allocation. He suggested that the FOMC needed “to rely on other methods to change relative asset prices — longer-term rates relative to short-term rates, private rates relative to government rates, nominal rates relative to expected inflation — and that is where the communications and the size and the composition of the asset portfolio come in.” Despite this endorsement of credit allocation, Kohn was uncomfortable with it: “I wish we didn’t have to be there. But I don’t see any evidence that the private sector is going to start lending anytime soon on its own.“29

Other Committee members, however, opposed the Fed’s involvement in selective bond buying. Lacker argued that the FOMC “should strive to maintain as much distance as possible from credit allocation.” Moreover he suggested that, to the extent that it was doing something other than targeting the funds rate or some monetary aggregate, it “really isn’t doing monetary policy.“30 Observing that the Fed’s emergency lending had, up to that point, been through lending programs initiated by the Board of Governors rather than the FOMC, Plosser feared that unless there was greater clarity about the new operating regime it might “look as though we have lost control of monetary policy or that the FOMC, which sets the target funds rate, and the Board of Governors, which largely is controlling the liquidity provisioning, are at odds.“31 (Recall that both the TAF itself and the decision to sterilize its lending came from the Federal Reserve Board, not the FOMC.) Plosser preferred that the Fed purchase Treasury securities, including long-term Treasuries, rather than purchase riskier assets as authorized by Section 13(3) of the Federal Reserve Act.32 Aiding specific markets was, in Plosser’s opinion, the Treasury’s responsibility.33

Hoenig, Chicago Federal Reserve President Charles Evans, and Minneapolis Federal Reserve President Gary Stern also questioned the efficiency of directed bond buying. Stern specifically expressed the fear that, if credit allocation went too far, it would “interfere with what would otherwise be normal and healthy market adjustments.“34

Despite such opposition, the strategy of targeting specific assets prevailed. The consensus view was that expanding the monetary base per se would not be effective. Most members appeared to accept the view that the marked expansion of reserves associated with QE would not be accompanied by a similarly marked increase in bank lending or the money supply. Consequently, QE could not work via the “old Milton Friedman idea” of the portfolio balance mechanism — that is, by increasing the public’s holding of money relative to other assets.35 Rather, U.S.-style QE would stimulate the economy by reducing yields on particular assets. Exactly how this would work to stimulate the economy was not spelled out beyond Yellen’s suggestion that targeted bond buying “improves the availability of credit or lowers its cost, thus stimulating the economy.“36 That is, it would somehow reduce long-term yields and, thus, stimulate aggregate demand. Although Bernanke insisted that, in agreeing on this program, the Committee was “not going to be setting in stone an approach that will be used indefinitely,“37 the FOMC would, in fact, limit its quantitative easing for the duration of the program to a small set of assets — long-term Treasuries, agency debt, and agency MBS (that is, MBS issued by government-sponsored entities such as Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac).

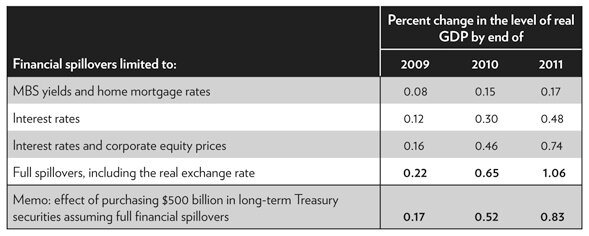

At the March 2009 FOMC meeting, the discussion moved on to the question of the required magnitude of what were now referred to as “large scale asset purchases” and, therefore, to questions about the response of asset yields and real output to such purchases. Two extreme proposals were under consideration.38 Option A would have the Fed purchase $500 billion in MBS and $300 billion of longer-term Treasuries, while option B would have it purchase $750 billion in MBS. According to estimates made by the board staff, a $500 billion purchase of long-term Treasuries would reduce the 10-year Treasury yield by 20 to 100 basis points, but a $500 billion purchase of agency MBS would have a larger effect on real GDP.39 According to staff member David Reifschneider, the evidence suggested

that these reductions spill over to yields on corporate bonds and other long-term instruments; if so, these interest rate movements should spark higher equity prices and a lower real exchange rate. In turn, household spending, business investment, and net exports should strengthen in response to lower borrowing costs, higher wealth, and greater international price competitiveness.40

But some Committee members found the staff estimates unpersuasive. Plosser asked why a purchase of MBS amounting to a little less than 10 percent of the market value of such securities would increase output by considerably more than a purchase of Treasuries constituting about 25 percent of the market. He wondered how the Fed could anticipate such large spillover effects from its MBS purchases while simultaneously justifying such purchases on the grounds that the MBS market was “dysfunctional.” He also asked how it could be that the Fed’s purchase of Treasuries was expected to cause the spread between corporate bond yields and Treasuries to rise, while its purchase of MBS was expected to causes the spread between them and corporate bonds to decrease.

Staff members’ answers to those questions were not reassuring. According to Joseph Gagnon, Treasury debt had increased a lot since the estimates had been made in December, so that “the range we get, which is quite large — 20 to 100 basis points — would need to be shifted down some.… We just don’t know within a big range where the answer is.” With regard to the anomalous behavior of the corporate/Treasury spread, Gagnon said: “The thought was that the Treasury purchases would be taking a safe haven out of the market and then that would lower Treasury yields more than other assets, so it would widen spreads. For MBS purchases, it seemed to us that just generally you’re helping remove private sector assets, so it should help all private sector assets relative to Treasuries.” When Plosser expressed continued puzzlement, saying, “It’s just a funny distortion, it seems to me,“41 Reifschneider responded tellingly:

Whether there are spillover effects from MBS into Treasuries or into high-grade corporates — there’s a huge uncertainty about that.… I think the way to interpret the model simulation results is that buying large amounts of securities, whether it’s Treasuries or MBS, has at least a fighting chance of bringing down the level of long-term rates. And if you can do that, and if that spills over into the stock market, the exchange rate, that sort of thing, then you potentially get a major stimulus to the real economy (emphasis added).42

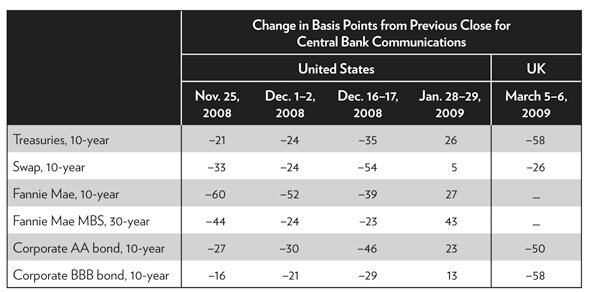

Throughout the rest of the discussion it was evident that board staffers disagreed among themselves about the magnitude of both the direct and spillover effects on bond yields and, hence, on its potential effects on output. According to staffer Trish Moser, the effects on long-term rates were likely to occur when the purchase was announced rather than when the securities were purchased:

It seems — both from our MBS purchase program and from the UK’s announcement — that a huge amount of the interest rate effect happens on announcement, not on execution. It doesn’t grow over time as the purchases get bigger and bigger and bigger. Boom — the rates fall. But that announcement effect happens because of the assumption that the central banks are going to keep buying for a while, not that they’re just going to do it for a month or two and then stop the program and go away.43

To sum up: The Federal Reserve Board staff maintained that, by purchasing a large quantity of security X, the Fed would reduce the yield on X by an uncertain amount roughly determined by the size of the purchase relative to the total size of the market for X. The decline in X’s yield would then spill over to the broader securities market. Why? The answer given was that the yields on X and yields on other securities had been correlated historically. The staff admitted that the extent of these spillover effects was itself difficult to determine. However, estimates of the announcement effects of LSAP already undertaken suggested that the effects might be large and that most of the effects would occur on the announcement rather than from the purchases per se. In other words: we don’t know if QE will work, but it might, and we don’t know what else to do anyway.

Quantitative Easing Theory: Initial Quantitative Easing Purchases

Informed only by these vague and highly uncertain conclusions, the FOMC voted for a “combined alternative” involving the purchase of $750 billion of MBS and $300 billion of Treasuries. The total purchase was thus larger than originally contemplated. This appears to have been motivated by the belief that most of the yield effects would occur on the plan’s announcement — the larger the announced purchase, the larger the “announcement effect” — and by the committee’s generally very pessimistic economic outlook. Yellen shared this pessimism:

I think we’re in the midst of a very severe recession — it’s unlikely to end any time soon. The optimal policy simulations would take the fed funds rate to −6 percent if it could, and because it can’t, I think we have to do everything we possibly can to use our other tools to compensate [emphasis added].44

Yellen and the Committee were unduly pessimistic; the recession officially ended just three months later, in June.

The Friedman portfolio-balance effect, which suggests that QE works by increasing the real money stock (a possibility that had been set aside at earlier FOMC meetings), came up again at the August 2009 meeting. Lacker noted that the Bank of America was holding enormous reserves that it was “planning to shift … into cash equivalents, like Treasuries and agencies, that are higher yielding and have a lower cost to carry.“45 He asked how far long-term yields would have to fall to get banks to not do this, and instead continue to hold excess reserves. Bernanke responded: “This is how quantitative easing works. You induce banks to substitute away from reserves, but they have to hold reserves in the end.“46

Bernanke’s answer was not entirely correct, however. It is true that neither individual banks nor the banking system as a whole can reduce the total quantity of bank reserves. But individual banks and the banking system can reduce the outstanding quantity of excess reserves by purchasing Treasuries or by making additional loans, and thereby causing the supply of deposits to grow. If all banks undertook the actions that Lacker expected the Bank of America to take, there would have been a massive increase in the money supply.

Board staffer Brian Sack later remarked that Lacker’s Bank of America example was “basically describing the portfolio balance effect.“47 However, as we’ve seen, the FOMC dismissed Friedman’s version of the portfolio-balance effect: the idea that QE could work by increasing the money supply. Indeed, the Fed took steps to encourage banks to hold excess reserves to prevent the money supply from increasing. The only sort of portfolio balance effect that Bernanke was prepared to entertain was the sort he had described briefly at the December 2008 FOMC meeting and that he and others later described in more detail.48 This version of the portfolio-balance effect required banks to hold large quantities of excess reserves rather than increasing the supply of money, the goal being to prevent the money supply from expanding rapidly because that would result in higher-than-desired inflation.

The effectiveness of LSAP was a topic of debate within the FOMC throughout 2009, with some members revising their own views over time. For example, at the April 2009 meeting Yellen claimed that that there was “compelling evidence that purchases of longer-term Treasury securities worked to bring down borrowing rates and improved financial conditions more broadly,” and that, having “tested the waters,” it was time for the Fed “to wade in by substantially increasing our purchases of Treasury securities.“49 By the June meeting she had changed her mind:

Initially I was an enthusiast for long-term Treasury purchases. I thought the purpose of it was not only to improve liquidity and market functioning, but also to influence yields to push them down.… On theoretical grounds, I believe there’s a very strong case that they should have some effect, but it has been awfully hard to identify exactly what that effect is, and I think that we’re beginning to run into costs of pursuing that further… I would say the benefits don’t merit the costs, but I wouldn’t want to see Treasuries taken off the table if conditions were to deteriorate and attitudes were to change.50

Yellen did not explain why she changed her mind. What is clear, however, is that despite declining 51 basis points on March 18, 2009, compared with the previous day, the 10-year Treasury yield was 121 basis points higher on June 24 than it had been on March 18. Private yields were also generally higher. Quantitative easing did not seem to be having the desired effect.

Quantitative Easing Theory: Subsequent Elaboration

As we’ve seen, throughout its 2008-09 deliberations the FOMC developed only a very sketchy theoretical rationale for the Fed’s large-scale asset purchases. That rationale was, however, more fully developed in an influential 2011 paper by Joseph Gagnon, Mathew Raskin, Julie Remache, and Brian Sack.51 Gagnon is a former Federal Reserve Board economist now at the Peterson Institute; the others are economists at the New York Federal Reserve.

Gagnon and his coauthors assume that long-term yields are determined according to the so-called “Expectations Hypothesis” of the term structure of interest rates. According to this hypothesis, the yield on a long-term asset reflects the short-term interest rates that are expected to prevail over the course of the asset’s holding period plus a constant risk premium. For Treasury securities, the authors observe that the “most important component of the risk premium” is the term premium — that is, the premium arising from the fact that an unexpected change in current interest rates alters the price of longer-term securities more than that of short-term securities. The risk of a capital loss, or market risk, is therefore greater for long-term securities.52

The authors claim that large-scale purchases of longer-term Treasury securities can reduce Treasury yields by reducing the term premium.53 Specifically, they observe that when the Fed purchases longer-term Treasuries it shortens the duration of the remaining government debt held by the public. Duration, like maturity, is a measure of the sensitivity of an asset’s price to an interest-rate change — the longer the duration, the greater the change in price, and hence the greater the market risk. Although duration and maturity are identical only in the case of zero coupon bonds — that is, bonds that have no periodic interest (or coupon) payments — they are positively related. Fed purchases of long-term Treasuries should therefore reduce the risk premium on outstanding Treasury securities. Specifically, removing a considerable amount of high-duration assets from the market reduces the average duration of remaining assests in the market and thereby reduces the risk premium.

The authors claim, further, that the portfolio effects of targeted QE should

also spill over into the yields on other assets. The reason is that investors view different assets as substitutes and, in response to changes in the relative rates of return, will attempt to buy more of the assets with higher relative returns. In this case, lower prospective returns on agency debt, agency MBS, and Treasury securities should cause investors to seek to shift some of their portfolios into other assets such as corporate bonds and equities and thus should bid up their prices. It is through the broad array of all asset prices that the LSAPs would be expected to provide stimulus to economic activity.54

Importantly, the authors reject Bernanke’s suggestion that QE might work by signaling the Fed’s intention to “pursue a persistently more accommodative policy stance than previously thought.“55 They claim that such signaling is best accomplished, as it has been in the past, through FOMC statements indicating the likely future path of the Fed’s funds rate target.

The authors appear to have influenced Bernanke’s own understanding of QE theory, as reflected in his later statements on the topic, including that contained in his speech at the Kansas City Federal Reserve’s 2012 symposium at Jackson Hole, Wyoming. Bernanke explained the “portfolio balance” channel as follows:

One mechanism through which such purchases are believed to affect the economy is the so-called portfolio balance channel.… The key premise underlying this channel is that, for a variety of reasons, different classes of financial assets are not perfect substitutes in investors’ portfolios.… Imperfect substitutability of assets implies that changes in the supplies of various assets available to private investors may affect the prices and yields of those assets. Thus, Federal Reserve purchases of mortgage-backed securities (MBS), for example, should raise the prices and lower the yields of those securities; moreover, as investors rebalance their portfolios by replacing the MBS sold to the Federal Reserve with other assets, the prices of the assets they buy should rise and their yields decline as well. Declining yields and rising asset prices ease overall financial conditions and stimulate economic activity through channels similar to those for conventional monetary policy.56

Bernanke, however, also allows here for the possibility that LSAP might improve the broader economy by signaling an enduring change in the Fed’s policy stance:

For instance, they can signal that the central bank intends to pursue a persistently more accommodative policy stance than previously thought, thereby lowering investors’ expectations for the future path of the federal funds rate and putting additional downward pressure on long-term interest rates, particularly in real terms. Such signaling can also increase household and business confidence by helping to diminish concerns about “tail” risks such as deflation. During stressful periods, asset purchases may also improve the functioning of financial markets, thereby easing credit conditions in some sectors.57

Quantitative Easing Theory: A Critical Appraisal

Could QE reduce yields enough to produce a large increase in spending? This section critically assesses the theories offered in defense of the claim that this was likely.58

The Portfolio-Balance Channel

The presence of a portfolio-balance channel of the sort described by Bernanke, as well as Gagnon and his coauthors, depends crucially on an assumption that many, if not most, economists — possibly including most of those taking part in the FOMC’s post-2008 deliberations — might have scoffed at prior to the crisis. This is the assumption that bond markets are sufficiently “segmented” to allow purchases of particular assets to alter those asset’s specific yields.59

Financial markets are segmented only if investors prefer certain securities over others with very similar, if not identical, financial characteristics. For example, for the MBS market to be segmented, substantial numbers of investors must prefer to hold MBS even when otherwise identical securities (OIS) — that is, securities with the same degree of market and default risk — offer a somewhat higher yield. A preference for holding MBS must then be due to something other than their risk characteristics. If this is the case, however, there will be a spread between the yields on the two securities such that investors become indifferent about which security they hold. Let’s call this spread the “maximum yield difference” (MYD). Different investors may, of course, have different MYDs. For investors with no special preference for MBS, the MYD will be zero.

How does a large Fed purchase of MBS alter the yields on MBS and OIS? The answer depends on conditions just prior to the purchase. Because bond prices are very flexible, it’s reasonable to suppose the spread between OIS and MBS yields is somewhere between its lower bound of zero (where it would be if a majority of investors, considered in total investment terms, were indifferent between holding MBS or OIS), and some positive, but presumably not large, value.60 For the sake of simplicity, let’s suppose that investors’ MYDs are uniformly distributed between 0 and 1 percentage point. The equilibrium spread could then be anywhere within that range, depending on the distribution of wealth among the investors. However, for the sake of our thought experiment, let’s assume that it is exactly 50 basis points.

Now imagine that the Fed purchases a large quantity of MBS. The purchases increase the demand for MBS relative to the outstanding supply, raising their price and reducing their yield. The OIS-MBS spread therefore rises above 50 basis points, disrupting the initial equilibrium and causing MBS holders whose MYD is larger than 50 basis points to trade MBS for OIS. These trades will, in turn, cause the price of MBS to fall and their yield to rise and the price of OIS to rise and their yield to fall. Assuming that the pool of market participants does not change, this process will continue until the equilibrium spread returns to 50 basis points.

How much lower will yields be in the new equilibrium? That depends on a number of things, not the least of which is the relative sizes of the markets for MBS and OIS. If the market for OIS is small relative to the MBS market, the decline in yields would be relatively large because the increase in demand for OIS will be large relative to the size of the market, resulting in a relatively large increase in its price and a corresponding large reduction in its yield. If, on the other hand, the market for OIS is large relative to the MBS market, the decline in yields would be relatively small because the increase in demand for OIS would be relatively small. Indeed, if the OIS market is very large relative to the size of the MBS market, the effect on both yields would be tiny.

Of course, this example is very rudimentary. In contrast, real-world financial markets are very complicated. There are a myriad of securities differing along many dimensions, including maturity, degree of default risk, call provisions, amount of collateral, tax burden, and so on. Nevertheless the same principles hold. There always exists an MYD beyond which an investor will switch from one security to another with a higher yield, and this MYD is generally unlikely to be very large for securities with similar, but not identical, characteristics. Consequently, even very large Fed purchases of some particular security or group of securities can only be expected to produce modest changes in equilibrium yields if the amount of the purchase is small relative to the size of the entire market.61 The effectiveness of such purchases depends, then, not on their absolute size, but on the size of the asset purchase relative to the size of the entire market.

So what happens when we move from our simple thought experiment to the real world and we consider not only the Fed’s purchase of MBS, but Treasuries and agency debt as well? Compared to its pre-crisis asset purchases, the Fed’s purchases were enormous. Nevertheless they were quite modest relative to the overall size of the domestic — let alone the international — financial markets. For this reason several analysts doubted that QE could possibly have any significant effect on long-term yields via the portfolio-balance channel.62

Gagnon and his coauthors’ alternate portfolio-balance theory also depends on implausible assumptions. Specifically, they suggest that the effect on the term premium “may arise because those investors most willing to bear the risk are the ones left holding it. Or, even if investors do not differ greatly in their attitudes toward duration risk, they may require lower compensation for holding duration risk when they have smaller amounts of it in their portfolios” (emphasis added).63 In order for the first part of the authors’ conjecture to be correct, the remaining investors would have to be those having a high tolerance for market risk. While that might be the case, it is not obvious that it would be. On the contrary, it seems more likely that the investors who are most risk-adverse (that is, those who have the least tolerance for risk) would remain in the default-risk-free Treasury and agency-debt markets. They might also remain in the MBS market because of the Fed’s proclivity to support the market and the fact that most newly issued MBS were guaranteed by Freddie Mac, Fannie Mae, and Ginnie Mae and, hence, essentially by the government.

Gagnon and his coauthors’ second claim — that QE can reduce bond yields by reducing assets’ average duration — is simply wrong. An investor’s aversion to market risk is what economists refer to as a “deep parameter” — something that is in an investor’s DNA, if you will. Duration risk is solely a function of the asset’s duration — the higher the duration, the greater the risk. To see why assets’ average duration is irrelevant, assume a market for otherwise identical zero-coupon bonds with maturities of 1 to 30 years in which all of the investors have the same tolerance for market (duration) risk. Now assume the Fed purchases all of the bonds in the market with maturities of 10 to 15 years. These purchases would reduce the remaining assets’ average duration. But would the purchases alter the term premiums on bonds with maturities of 16 to 30 years? Of course not; the duration of the bonds with maturities of 16 to 30 years hasn’t changed. Consequently, neither has their duration risk. Investors’ tolerance for market risk has not changed, either. The term premium — that is, the spread between a 1‑year and a 30-year bond (the 30-year bonds term premium) — would be exactly the same as it was before the purchases. Quantitative easing can only reduce term premiums if participants who are the least averse to market risk stay in the market, while those who are most adverse to market risk leave.64 But there is no reason this will necessarily happen. Indeed, as the thought experiment above illustrates, it is at least as likely that investors who are least risk-tolerant will remain. In those circumstances, the term premium could actually go up.

The Signaling Channel

According to the signaling channel, QE is another way for the Fed to supply “forward guidance” — an alternative, that is, to having the FOMC declare that the funds rate will remain near zero for “an extended period,” or until some particular date or event. Intriguingly, the signaling channel is based on assumptions that are inconsistent with those underlying the portfolio channel. The portfolio-balance theory requires the long-term and short-term markets to be segmented — that is, populated by investors with relatively high MYDs. The signaling-channel theory, by contrast, requires long-term yields to be consistent with the Expectations Hypothesis, which presupposes perfect substitutability across the term structure. In other words, the market must be populated by investors whose MYD is zero. Consequently, both theories cannot be right; if one of the channels is effective, the other cannot be.65

At least three requirements must hold for the signaling channel to work. First, market participants must interpret QE announcements as a signal that the FOMC intends to leave the federal funds rate target at zero for a longer period of time than the participants had previously anticipated. That is, the FOMC’s quantitative easing policy must alter market participants’ expectation for the time path of the policy rate. Second, the FOMC’s commitment with respect to the time path of the policy rate must be credible — that is, market participants must believe the FOMC will not renege on the commitment.66 If either of these conditions is not met, QE cannot reduce long-term yields through the signaling channel.

Finally, the signaling mechanism also requires that the Expectations Hypothesis holds. That is, long-term yields must reflect nothing apart from the expected path of short terms rates and a constant risk premium. Because the Expectations Hypothesis has been massively rejected over a variety of sample periods and monetary policy regimes, and through the use of alternative tests and data, serious doubts have been raised concerning the practical relevance of the signaling channel.67 Nor is the empirical failure of the Expectations Hypothesis surprising: it is well known that interest rates are essentially unpredictable beyond horizons of a few months. It is therefore difficult to believe that rational economic agents would continue to price long-term debt based on expectations of the path of short-term interest rates that are virtually certain to be proven wrong.

The Fed’s QE policy was based on the shakiest of theoretical foundations. Bernanke came close to admitting as much in an interview he gave last January at the Brookings Institution, when he said, “The problem with QE is it works in practice, but it doesn’t work in theory.“68 But even this admission on Bernanke’s part begs an important question: did QE actually work in practice? It is to that question that I now turn.

Empirical Evidence on the Effects of Quantitative Easing

This section reviews empirical evidence concerning the effectiveness of both the signaling and portfolio-balance channels of QE.

The Portfolio-Balance Channel: Event Study Evidence

Most of the studies that claim to find evidence that QE reduced long-term yields are what are known as “event studies.” Such studies calculate the change in a variety of long-term yields from prior to an announcement to a period after the announcement. The announcement effect is usually measured from the day before the announcement to the day of the announcement. According to this approach, if QE is effective, bond yields should decline substantially when large-scale asset purchases are announced.

Several economists have questioned the reliability of such studies on the grounds that QE announcements occur in FOMC policy statements that also contain other news capable of influencing bond yields.69 As Columbia University economist Michael Woodford notes, “Each statement always contains a summary of the FOMC’s view of the outlook for real activity and inflation, and a statement indicating greater perceived downside risk or less worry about inflation on the horizon.“70 The evidentiary value of the event-study announcement effects depends on whether non-quantitative-easing FOMC announcements are properly controlled for.

My own detailed analysis of 53 QE announcements commonly used in the event-study literature found that for all but 11 of them, the reported “QE announcement effect” is either statistically insignificant or due to something other than the QE announcement.71 Of the remaining 11 announcements, only the one that followed the November 25, 2008, meeting, declaring that the Fed would purchase $600 billion in agency debt and MBS, contained no other news. The remaining 10 announcements contained additional news that could have contributed to the observed announcement effects.

As for that November 25, 2008, announcement, it actually occurred before the U.S. bond market opened, which means that the measured effects could have reflected developments both before and after the announcement. Using data on millisecond transactions for on-the-run 10-year Treasury bonds during a 24-hour period before and after the announcement, I found that the 10-year yield declined by only 5 basis points in the 45 minutes after this announcement. It is therefore unlikely the 25-basis-point reduction in the 10-year yield occurring that day was entirely attributable to QE news.

In short, the announcement effects reported in the QE event-study literature do not offer convincing evidence of the effectiveness of QE.

The Portfolio-Balance Channel: Other Evidence

Another strand of the empirical literature on the effectiveness of QE focuses on whether it reduces long-term yields by shortening the maturity (or duration) of the debt held by the public. The methodology used in this literature is somewhat novel: the researchers investigate the relationship between the maturity (or duration) of the public’s holding of debt and (a) long-term bond yields or (b) estimates of the term premiums before the adoption of QE. The researchers then use these estimates to infer the effect of QE on yields or term premiums.72

Gagnon and his coauthors, who introduced this approach in their 2011 paper, investigate the relationship between several measures of the average maturity of the public’s holding of government debt and both the 10-year Treasury yield and an estimate of the term premium on 10-year Treasuries conditional on a variety of economic variables. The data are monthly, covering a sample period from January 1985 through June 2008. From their estimate of that relationship, the authors infer that the announced purchase of $1.75 trillion in debt by the Fed should have reduced the 10-year Treasury term premium by between 32 and 82 basis points.

I carried out my own analysis of the authors’ research and found two important errors.73 First, they make a serious analytical error in calculating their series on the public’s holding of government debt. Specifically, they subtract foreign official holdings of agency and private debt from the public’s holding of government debt; this is the logical equivalent of subtracting apples from oranges. Mathematically it can be done only because these incomparable measures are expressed in dollars. As it happens, the foreign official holdings of agency and private debt became very large toward the end of the authors’ sample period, which means their measure of the public’s holding of Treasury debt turns negative beginning in November 2007. Of course, the public’s holding of debt cannot, in reality, be negative.

Second, the authors fail to account for the fact that their measure of bond term premiums and their measure of public debt both trended down over their sample period. It is well known that two time series will be positively correlated when they trend in the same direction and negatively correlated when they trend in opposite directions, even if there is no fundamental relationship between them.

Employing 3 different measures of bond yields and 10 measures of public debt used in the literature, I found that when the authors’ public debt measure is corrected and the trends are accounted for, there is no statistically significant relationship between either the term premium or the 10-year Treasury yields and any of the 10 public debt measures used. I did find a statistically significant relationship between two of the debt measures and the yield curve slope measure used by James D. Hamilton and Jing Cynthia Wu in their 2012 paper, but the estimated effects were small — much smaller than the announcement effects reported in the event-study literature.74 Hence, these estimates suggest that the Fed’s LSAP had, at best, a modest effect on term spread.

Empirical Evidence: Signaling Effects

Bernanke, Yellen, and others have suggested that QE announcements provide forward guidance about the policy rate. This so-called signaling channel has also been investigated using the event-study methodology. However, it is difficult to determine whether QE announcements reduced yields via the signaling channel because it is difficult to know what market participants’ expectations for the time path of the funds rate were prior to QE or FOMC path announcements. It is also hard to know whether market participants believed the various commitments to be credible.

Woodford suggests that “the most logical way to make such commitment achievable and credible is by publicly stating the commitment, in a way that is sufficiently unambiguous to make it embarrassing for policymakers to simply ignore the existence of the commitment when making decisions at a later time” (italics in the original).75 He goes on to suggest that “the ‘cleanest’ test of the effects of forward guidance” (that is, of the signaling channel) is the reaction to the FOMC announcements made on August 9, 2011, and January 25, 2012: on the former date, the FOMC announced that the funds rate would remain exceptionally low “at least through mid-2013”;76 on the latter, the FOMC extended the period to “at least through late 2014.“77 Woodford evaluated the effectiveness of these announcements using the high-frequency response of U.S. dollar overnight index swap rates immediately following them. The one-month U.S. dollar overnight index swap rate is considered to be the market’s expectation for the overnight federal funds rate one month in the future.

The problem, of course, is that Woodford’s analysis suffers from the same problem that he identified as affecting all event studies; namely, that FOMC policy statements contain other news, which makes it difficult, if not impossible, to know whether the immediate response was due to the forward guidance news or other news in the announcement.78 What’s more, the high-frequency response only measures the immediate response. In order for the signaling channel to influence long-term yields, however, the effect must be persistent. In other words, the high-frequency response provides no information about the persistence of the supposed announcement effect, which is critical for QE to be effective via the signaling channel.

Michael Bauer and Glenn Rudebusch further investigated the effectiveness of the signaling channel by using several term-structure models to decompose daily changes in the 10-year Treasury yield on specific announcement days into “path” and “term-premium” components.79 They found that the change in the path, which they attribute to the signaling effect of QE, is about twice as large as the term-premium component. This finding is interpreted as evidence that QE worked through the signaling channel. But, again, Bauer and Rudebusch’s analysis is plagued by the same problems that affect all event studies. Just as importantly, their results are specific to the models they used to generate them and can only be considered relevant if long-term yields are indeed determined in accordance with the Expectations Hypothesis — that is, as a sum of the expected short-term interest rate over the asset’s holding period plus a constant risk premium.

An alternative way of investigating the signaling channel is to see how forward guidance announcements affected FOMC participants’ expectations for the path of the funds rate. If those announcements had little effect on FOMC participants’ expectations, it is difficult to see how they could have had a large effect on market participants’ expectations.

In 2012, the FOMC began periodically releasing FOMC participants’ “judgment of the appropriate level of the target federal funds rate” for the ends of particular, specified years.80 That new policy made it possible to see how QE or other forward guidance announcements changed FOMC participants’ fund rate expectations.

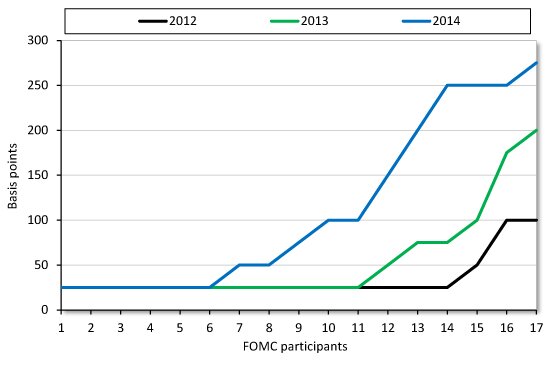

How did the two announcements that Woodford suggests provide the cleanest test of forward guidance affect FOMC participants’ expectations for the path of the funds rate?81 Figure 1 Figure 1, “FOMC Participants’ Expected Path of the Funds Rate (as of January 2012)” shows FOMC participants’ expectations for the funds rate reported in the January 2012 FOMC minutes for the end of 2012, 2013, and 2014. The participants’ expectations are rounded to the nearest 25 basis points. In spite of the FOMC’s apparent commitment to keep the funds rate between zero and 25 basis points, “at least through late 2014,” 35 percent of the participants expected the funds rate to be above this “exceptionally low level” by the end of 2013, while 65 percent expected it to be above that level by the end of 2014 — in most cases, significantly so.82 Apparently these forward-guidance announcements did not yield a consensus among FOMC participants. It is therefore difficult to see how they could have had a large effect on market participants’ expectations for the funds rate.

Source: Minutes of the Federal Open Market Committee meetings.

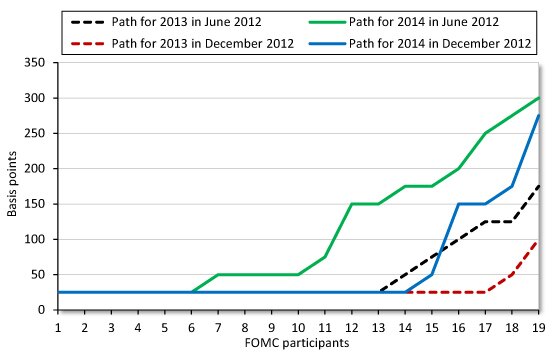

On September 13, 2012, the FOMC further extended its forward guidance to “at least through mid-2015,” and announced “QE3”: specifically, the FOMC’s intention to increase the Fed’s “holdings of longer-term securities by about $85 billion each month through the end of the year.“83 Figure 2 Figure 2, “Change in FOMC Participants’ Expectations (between June and December 2012)” shows the effect of this announcement on FOMC participants’ expectations for the funds rate between June 2012 and December 2012. These announcements had a large effect on FOMC participants’ expectations of the path of the funds rate. The number of participants who believed that the funds rate would be higher than 25 basis points by the end of 2013 fell from 6 to 2; for 2014 the number fell from 13 to 5. These are substantial changes in the expectations for the funds rate. Nevertheless, 26 percent of the participants still believed that the funds rate would be higher than 25 basis points by the end of 2014. The FOMC switched from time-dependent forward guidance to state-dependent forward guidance at its December 2012 meeting, announcing that the funds rate would remain exceptionally low “as long as the unemployment rate remains above 6.5 percent.“84 Nevertheless, two members at the December 2012 meeting believed the funds rate would be 50 basis points or higher by the end of 2014, and all but one of the participants expected the funds rate to be higher than 25 basis points by the end of 2015.

Source: Minutes of the Federal Open Market Committee meetings.

Finally, at its January 2013 meeting, the FOMC announced it would continue to purchase MBS and Treasuries at the pace of $85 billion a month. This extension of QE3 had virtually no effect on FOMC participants’ expectations for the fund rate for 2014 or 2015. The February 2013 FOMC minutes show that the participants’ expectations for the funds rate for 2014 and 2015 are nearly identical to those for December 2012.

The fact that these announcements did not produce a consensus for FOMC participants’ expectations, and that the effect on FOMC participants’ expectations was often weak, suggests that these QE- and forward-guidance announcements may not have had a large effect on market participants’ expectations for the path of the funds rate. By extension, therefore, these announcements are unlikely to have had much effect on long-term yields.

There is yet another simple way to investigate the effectiveness of forward guidance and, hence, the signaling channel of QE. This method comes from noting that if the behavior of long-term yields were largely determined by QE and forward guidance, one would expect to find a number of discrete downward jumps in the time-series of long-term yields corresponding to dates of the most important QE- or forward-guidance announcements. Discrete jumps in long-term yields should occur because, as Gagnon and his coauthors note, “a credible announcement that the Federal Reserve will purchase longer-term assets at a future date should reduce longer-term interest rates immediately. Otherwise, investors could make excess profits by buying the assets today to sell to the Federal Reserve in the future.“85 This should happen for credible forward-guidance announcements as well. Hence, there should be a marked downward shift in long-term yields corresponding to important QE- and forward-guidance announcement dates. On the other hand, if these announcements did not change market participants’ expectations for the path of the funds rate, or if market participants did not find these announcement credible or believed the Fed’s actions would have little or no effect on long-term yields, there would be no marked downward shift in long-term yields.86

Source: Minutes of the Federal Open Market Committee meetings.

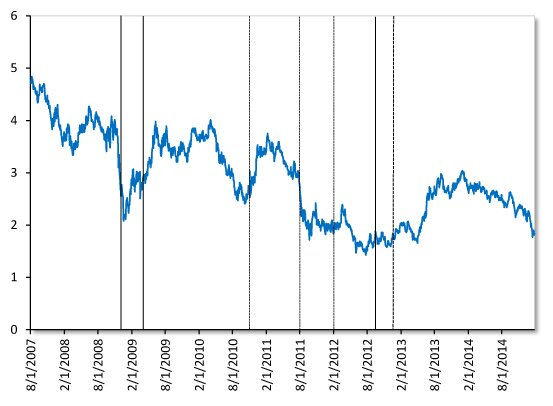

Figure 3 Figure 3, “Ten-year Treasury Yield” shows the daily 10-year Treasury yield from August 1, 2007, through January 27, 2008. The vertical lines denote important QE- and forward-guidance announcements (November 25, 2008; March 18, 2009; November 3, 2010; August 9, 2011; and January 25, September 13, and December 12, 2012). There are only two dates that appear to be associated with a sharp and persistent drop in the 10-year Treasury yield: November 25, 2008, and August 9, 2011. This behavior is misleading for the November 25, 2008, announcement because, as noted above, the millisecond transaction data for on-the-run 10-year Treasury bonds that I examined indicate that there was no immediate reaction to this announcement. This makes it unlikely that the observed decline in the 10-year yield was caused by the announcement. Moreover, 65 basis points of the 190-basis-point drop in the 10-year Treasury yield between October 31 and December 30 occurred before the November 25 announcement.

A detailed look at the August 9, 2011, announcement shows that most of the decline in the 10-year Treasury yield occurred before the announcement. The Treasury yield declined by 61 basis points from July 27 to August 8, fell by an additional 20 basis points to 2.2 percent on August 9, and then fluctuated around that level for the next four weeks before declining further. All in all, Figure 3 provides little, if any, evidence that these important QE- and forward-guidance announcements had much effect on the 10-year Treasury yield.

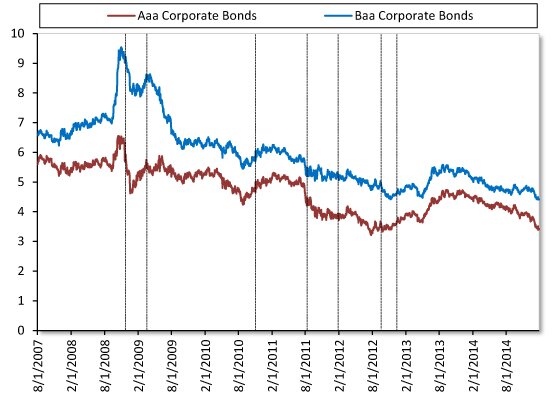

That said, the effect on Treasury yields, while interesting, is not especially relevant. The yields that are most likely to influence spending decisions are those on private securities. Figure 4 Figure 4, “Aaa and Baa Corporate Bond Yields” shows the same analysis as above applied to Aaa and Baa corporate bonds. The results indicate that there was no immediate, persistent reduction in either yield following any of the seven announcements. Moreover, like the 10-year Treasury yield, the corporate yields had begun declining significantly during the days prior to the announcements.

Source: Minutes of the Federal Open Market Committee meetings.

In short, there is virtually no evidence that the seven important QE announcements generated immediate, substantial, and persistent declines in long-term yields, as should have happened if the purchases served to reduce market participants’ expectations regarding the future course of the federal funds rate. In fact, there is no evidence that QE worked to reduce long-term yields at all — whether via signaling effects or via the portfolio-balance channel. That is to say, there is no credible evidence that QE worked as Bernanke and others thought it would.87

The Bearing of QE on Output and Employment

Quantitative easing was supposed to increase spending (aggregate demand) and thereby increase output and employment through the interest rate channel of monetary policy. That is, lower long-term yields were supposed to stimulate spending on capital goods and consumer durables. Many argue — with some justification — that QE might instead have been far more effective if the increase in the monetary base that it entailed had been allowed to lead to a corresponding increase in the money supply. Such a policy closely resembles the one that Friedman and Schwartz say could have averted the Great Depression. By easing credit conditions, it would have boosted general spending.

But as we’ve seen, the Fed took steps to prevent the supply of credit from increasing substantially in response to QE, out of a concern that a significant increase in lending would have inflation consequences, and because they had faith in the alternative interest rate channel. The trouble is that the interest rate channel can only work if QE actually lowered long-term yields and those reduced long-term yields in turn resulted in a significant increase in aggregate demand.

How important, then, are yields as a determinant of overall spending? The popular answer before 1980 was “not very.” The then-dominant Keynesian view was that monetary policy was ineffective because the interest rate channel — the only one Keynesians took seriously — was weak. Indeed, the lack of response of aggregate demand to changes in interest rates was the principal reason why, prior to the early 1980s, Keynesian economists insisted that monetary policy could do little to affect either output or inflation.

Of course, economists changed their tune after the Fed, under the leadership of Paul Volcker, tamed the double-digit inflation of the late 1970s and early 1980s. Volcker’s monetary policy, which explicitly aimed to reduce inflation by reducing the growth of the money supply, was followed by a remarkable and permanent reduction in inflation and by back-to-back recessions (January-July 1980 and July-November 1982). Monetary policy, once viewed as totally ineffective, was suddenly thought to be very effective. In a 2010 paper, I pointed out that this remarkable epiphany occurred despite the fact that none of the reasons for believing monetary policy was ineffective had changed.88

The Keynesian belief that monetary policy was ineffective rested on empirical studies that found investment and other spending were unresponsive to changes in interest rates. That evidence was supported by industry surveys showing that the interest rate was relatively unimportant for investment decisions. Consumer spending can also be insensitive to changes in interest rates, in part because some consumer rates, such as the interest rates on credit cards, tend to remain unchanged even when market rates change.89 The Keynesians went wrong, not in assuming that the interest rate channel was weak, but in ignoring other channels by which monetary policy might influence aggregate demand.

Ironically, Bernanke had himself noted the ineffectiveness of the interest rate channel of monetary policy in a highly cited paper, “Inside the Black Box.“90 He and coauthor Mark Gertler explained that the effectiveness of monetary policy depended on what they called the “credit channel” — that is, on its ability to fuel additional bank lending.91 Elsewhere, Bernanke had also noted that Japan’s QE policy didn’t seem to have a great deal of effect, primarily because the banks would not lend out the reserves that they were holding.92

Yet in rationalizing and implementing QE, both Bernanke and Yellen relied on the interest-rate-channel approach, and hence on the assumption that overall spending is sensitive to changes in interest rates.

In fact, QE was unlikely to stimulate aggregate demand so long as banks were content to impound the additional credit provided by the Fed’s asset purchases as excess reserves. It may seem incredible that the same policy that failed to work in Japan could have had an important measurable effect in the United States merely because the increase in excess reserves was accomplished by purchasing longer-term Treasuries, agency debt, and MBS rather than shorter-term Treasuries. Financial markets are highly competitive and efficient, after all. They most closely resemble the perfectly competitive markets of economic textbooks. Given their size and efficiency, it is difficult to believe that the distributional effects of the FOMC’s quantitative easing policy could have had a significant effect on either relative yields or the level of the entire interest rate structure. The fact that so many people apparently have come to believe that QE was effective is a testament to the idea that people will believe something if it is repeated often enough — especially if it is repeated by those in authority. Logic and evidence appear to have taken a back seat to the blind faith of the public, and the Fed itself, in the power of central banking.

Quantitative Easing’s Unintended Consequences

Although QE did not have the consequences its proponents intended, it did have unintended consequences. This was bound to be the case: changes in policy alter the perceived state of the economy, and people are bound to respond to such changes in some fashion.

Some unintended consequences are relatively easy to predict. For example, a monetary policy directed at keeping interest rates on low-risk securities near zero for a long period of time — over seven years and counting — is sure to cause people to seek higher yields by purchasing more risky assets. The Fed’s decision to purchase large quantities of longer-term Treasuries, for example, encouraged pension funds to hold riskier securities in order to generate the returns necessary to meet their present and expected future obligations.93 I anticipated this result when the LSAP was announced, and suggested it be referred to as the “force pension funds to hold more risky portfolios” policy.