The recent rise in American economic nationalism has accompanied the view that past restrictions on foreign competition were successful in achieving stated policy objectives: decreased imports, increased jobs, industrial revival, open foreign markets, and economic prosperity more broadly. Politicians and pundits use such assertions to justify new nationalist economic proposals, but they ignore a vast repository of academic analyses and contemporaneous reporting that show that American trade protectionism—even in the periods most often cited as “successes”—not only has imposed immense economic costs on American consumers and the broader economy, but also has failed to achieve its primary policy aims and fostered political dysfunction along the way.

This paper surveys academic literature from three periods of American history: from the founding to the United States’ entry into the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) in 1947; from the GATT’s early years to the creation of its successor, the World Trade Organization (WTO), in 1995; and the current WTO era. These surveys show that, contrary to the fashionable rhetoric, American protectionism has repeatedly failed as an economic strategy.

A renewed focus on international trade’s disruptions to the U.S. economy, while worthwhile, has spawned troubling suggestions that the U.S. government should be more willing to experiment again with protectionism to help American workers and the economy. This paper should help to counter such ideas. History is replete with examples of the failure of American protectionism; unless our policymakers quickly relearn this history, we may be doomed to repeat it.

Introduction

American economic nationalism has risen in recent years, both fueling and fueled by President Donald Trump’s election. With it has risen the view that protectionism has been an effective policy throughout the nation’s history. Trump and many others have perpetuated this view, which holds that past restrictions on foreign competition were successful in achieving their stated policy objectives: decreased imports, increased jobs, industrial revival, opened foreign markets, and American economic prosperity more broadly. These purported “successes” have been used to justify a new round of nationalist economic proposals.

This revisionist history, however, ignores a vast repository of academic analyses of and contemporaneous reporting on the periods and policies in question, which show the many failures of American trade protectionism. It relies instead on well-worn protectionist myths and the mere correlation of economic improvement with protectionist experimentation. But contrary to what often appears in the news and on the campaign trail, the actual scholarship paints a much different picture. It demonstrates that American protectionism—even in the periods most often cited as “successes”—has not only imposed immense economic costs on American consumers and the broader economy but also has failed to achieve its primary policy aims, fostering political dysfunction along the way.

This paper surveys academic literature from three periods of American history, demarcated by milestones in the evolution of the U.S. and multilateral trading systems: from the founding to the United States’ entry into the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) in 1947; from the GATT’s early years to the creation of its successor, the World Trade Organization (WTO), in 1995; and the current WTO era. These surveys show that, contrary to the fashionable rhetoric, American protectionism has repeatedly failed as an economic strategy.

Pre-GATT

U.S. history from the Founding through the early 20th century shows protectionism decreasing in effectiveness and increasing in costs for consumers and the economy more broadly. Multiple academic studies of the period between the Civil War and the Great Depression—often argued to be a golden era of American tariffs and industrial prosperity—show protectionism to have inhibited, rather than facilitated, industrial and broader economic growth. Instead, other economic factors—particularly rapid population expansion—drove American growth during this era. The protectionism of this era is also shown to have fostered modern American lobbying and rent seeking and, as a result, to have been closely associated with political corruption. Overall, however, pre–20th century U.S. trade policy provides few real economic lessons for modern policymakers because of the stark social, legal, and economic differences between that period and today.

From GATT to WTO

The findings from numerous studies of protectionist measures during the GATT period of general trade liberalization are unequivocal: U.S. protectionism not only produced far higher total economic costs than benefits but also, more often than not, failed even to achieve its intended objective, whether that be the rejuvenation of an ailing American industry and its workforce or the opening of new U.S. export markets. In particular, these studies show the high economic costs of U.S. protectionism. For example, studies of specific U.S. import restrictions between 1950 and 1990 found that the measures annually cost U.S. consumers an average of $620,000 in current dollars per job supposedly saved in the protected industry at issue. By contrast, at the current hourly U.S. manufacturing wage of $20.69, a typical factory worker makes a little over $41,000 per year.

Studies also found that protectionist measures failed in most cases to prevent further increases in imports or declines in U.S. jobs, finding only one instance—the bicycle industry—in which protectionist measures apparently resuscitated the industry in question. One analysis found that threats of retaliation through section 301 of U.S. trade law failed to achieve even partial success more than half the time, with actual retaliation working less than 20 percent of the time. Even the most heralded examples of American protectionist successes during this era—motorcycle safeguards that supposedly saved Harley-Davidson and the U.S.-Japan Semiconductor Trade Agreement—have been revealed to have imposed immense costs on U.S. consumers and companies for very little, if any, actual gains.

The outcomes would likely be worse if similar policies were implemented today, because of increased American integration into the global economy, the proliferation of global supply chains, the rise of other economic powers, and the creation of the WTO. Thus, protectionism today would yield even more pain for even less gain.

WTO

Following the advent of the World Trade Organization in 1995, American unilateral protectionism subsided and was relegated to relatively few trade barriers on politically sensitive goods and services dating back decades and to narrow administrative actions under U.S. “trade remedy” laws. The results of this protectionism, however, were no better than the previous eras’ and arguably much worse, given the U.S. participation in the WTO and further integration of the U.S. and global economies. Both created tangible ramifications (i.e., new prospects of retaliation and greater harms to import-dependent U.S. companies) that did not previously exist.

Macroeconomic studies continue to show that U.S. protectionism imposes significant harms on American consumers and the broader economy. Examinations of trade remedies in specific sectors—steel, high-tech goods, softwood lumber, paper, and tires—show massive consumer costs and the failure to revive the companies seeking protection. The U.S. antidumping law has repeatedly been found not only to hurt U.S. consumers and many large American exporters but also to only rarely improve the state of the protected industry. Instead, what often lies in the wake of protection is bankruptcy for the very firms that lobbied for protection. Other nontariff barriers, such as those on meat labeling, sugar, and maritime shipping, have proven no better and, in many cases, have led to foreign retaliation or the threat thereof.

General Conclusions

In recent years, academic work and political commentary have focused on whether the “free trade consensus” view in America may have underestimated the disruptions to the U.S. economy caused by heightened import competition. This discussion, while worthwhile, has spawned troubling suggestions from scholars, pundits, and politicians that the U.S. government should be more willing to experiment again with protectionism to help American workers and the economy, particularly the manufacturing sector. This paper should help disabuse them of such ideas.

With little doubt, the United States has struggled in recent years to adapt to significant economic disruptions, whether due to trade, automation, innovation, or changing consumer tastes. How we should respond to these challenges warrants discussion and consideration of various policy ideas. What should not be up for debate, however, is whether protectionism would help to solve the country’s current problems. History is replete with examples of the failure of American protectionism; unless our policymakers quickly relearn this history, we may be doomed to repeat it.

Survey

The following survey of the academic literature and contemporaneous reporting is broken down into three sections: from the nation’s founding to the GATT in 1947; the GATT period of 1947–1995; and the modern WTO period. The survey shows that American protectionism has repeatedly failed as an economic strategy, imposing far greater costs than benefits and frequently failing to achieve even its most basic objectives.

PRE-GATT Period (Founding to 1947)

The period of U.S. history from the nation’s founding through the early 20th century shows decreasing effectiveness of protectionism and increasing costs for consumers and the economy more broadly. Put simply, early to mid–19th century protectionism produced a mixed bag of results, while the protectionism of the late 19th and early 20th centuries was generally a small, but very real, failure. Multiple academic studies of the period between the Civil War and the Great Depression—often argued to be a golden era of American tariffs and industrial prosperity—show that protectionism inhibited, rather than encouraged, industrial and broader economic growth. Instead, other economic factors—particularly rapid population expansion—drove American growth during this era. The protectionism of this era is also shown to have fostered modern American lobbying and rent seeking and, as a result, to have been closely associated with political corruption. The historiography of this era will be examined in more detail later.

Despite certain political pronouncements to the contrary, pre–20th century U.S. trade policy provides few real lessons for today. First and most basically, the data available are limited. But more importantly, we live in a strikingly different world today than the one inhabited by supposed protectionist champions such as Alexander Hamilton and Abraham Lincoln. Trade among nations was far less developed; trade barriers were generally higher everywhere; national economies were much less diversified, reliant mainly on agriculture and only later on some basic manufacturing; communications and shipping were inefficient and costly; and there was no rules-based multilateral trading system for countries to commit to trade liberalization and for adjudicating disputes.1

Finally, tariffs were the United States’ only source of revenue, thus limiting legislators’ ability either to zero them out or to make them real and broad-based barriers to imports. This latter check is particularly noteworthy, as economic historian Douglas Irwin documented with respect to Alexander Hamilton’s 1791 “Report on Manufactures,” which many consider holy scripture of America’s protectionist history:

Although Hamilton’s proposals for bounties (subsidies) failed to receive support, virtually every tariff recommendation was adopted by Congress in early 1792. These tariffs were not highly protectionist because Hamilton feared discouraging imports, which were the critical tax base on which he planned to fund the public debt.… [Thus,] most of Hamilton’s proposals involved changes in tariff rates—raising some duties on imported manufactures and lowering some duties on imported raw materials.… Despite these tariff changes, Hamilton was not as much of a protectionist as he is sometimes made out to be. Although Hamilton’s moderate tariff policies found support among merchants and traders, the backbone of the Federalist party, disappointed domestic manufacturers soon came to embrace the much more draconian trade policies of the Republican party led by Jefferson and Madison.2

Today’s U.S. policymakers, by contrast, face no revenue constraints on their ability to use tariffs to achieve protectionist ends (though, as will be noted, they face many others). For these reasons, 19th century protectionism provides only limited lessons for the conduct of 21st century trade policy.

Nevertheless, because proponents of protectionism continue to cite this era as an example of protectionist success, it is worth reviewing the various reports and academic studies that have found significant costs to 19th century American protectionism and few unequivocal gains. These findings are summarized in the following sections.

The Early Years. Protectionism during the pre–Civil War era had mixed results. Irwin, for example, examined President Thomas Jefferson’s 1807–1809 embargo on almost all foreign trade and found that “the price of imported commodities rose by about a third as the number of ships entering U.S. ports fell to a trickle and imports became increasingly scarce.” He calculated that “the static welfare cost of the embargo was about 5 percent of [gross domestic product (GDP)],” thus inflicting “substantial costs on the economy during the short period that it was in effect.”3 In a subsequent study, Irwin and Joseph Davis found that the embargo, combined with the reductions in imports caused by the War of 1812, “did not decisively accelerate U.S. industrialization as trend growth in industrial production was little changed over this period.” Instead, they found that the trade restrictions “may have had a permanent effect in reallocating resources from trade-dependent industries (such as shipbuilding) to domestic infant industries (such as cotton textiles).” Put another way, “the United States emerged from the War of 1812 with a different allocation of resources between these two industrial sectors, but not more industrial production overall.”4 Irwin and Peter Temin then examined the antebellum tariffs on cotton textiles, which some researchers have credited with saving the U.S. textile industry. They found that data from 1826 to 1860 show that the industry could have survived even if the tariffs had been eliminated because “American and British producers specialized in quite different types of textile products that were poor substitutes for one another.”5

Other studies, it must be noted, have come to different conclusions about the benefits and costs of pre–Civil War American protectionism, finding that in some cases the benefits did indeed outweigh the costs. As economist Brad De Long noted: “The American South was a very large supplier in the world cotton market. Tariffs on manufactured imports may have raised America’s terms-of-trade enough to counterbalance (through a higher price of cotton in world markets) the deadweight loss from the tariff’s discouragement of valuable imports.”6 Hence, I offer the aforementioned note about the mixed results of pre–Civil War American protectionism (along with the disclaimer about how these results have almost no relationship to today).

Far more agreement exists, however, on the cronyism associated with early American protectionism and its effects on American lobbying and rent seeking. For example, economist Grant Forsyth found that the antebellum woolen textile industry in the United States was an early innovator in lobbying techniques that academics like James Buchanan and Gordon Tullock associate with the rise of 20th century pressure group lobbying and, as a result, with government growth. In particular, Forsyth found that the woolen textile industry built interstate, interindustry coalitions with key U.S. legislators and the media to achieve high tariffs that were otherwise unpopular in much of the nation—a stark change from the previous era of more limited, ad hoc lobbying and rent seeking. As a result, “the industry was not only successful in obtaining relatively high legislated tariffs by 1828, it also altered the traditional congressional avenues for obtaining information from aggrieved parties.”7

These findings are corroborated by the contemporaneous observations in Frank Taussig’s The Tariff History of the United States, which explores the history of American protectionism from the founding through the early 20th century.8 Not only did Taussig find typical consumer pains associated with protectionism—railroads paying twice as much for steel rails as they paid in England due to the 1870 tariff, for example—but he documented the cronyism that inevitably accompanied such policies. Vermont Congressman Rollin C. Mallary described the tariff bill of 1828 as giving “the manufacturer of iron all he asked, and more.”9 The Tariff Act of 1864, introduced and enacted in only five days, “contained flagrant abuses in the shape of duties whose chief effect was to bring money into the pockets of private individuals.”10 The Tariff Act of 1867 “was an intricate and detailed scheme of duties, prepared by the producers of the articles to be protected, openly and avowedly with the intention of giving themselves aid; and yet this scheme was accepted and enacted by the National Legislature without any appreciable change from the rates asked for.”11 Bad if not worse, the “whole cumbrous and intricate system—of ad valorem and specific duties, of duties varying according to the weight and the value and the square yard—was adopted largely because it concealed the degree of protection which in fact the act of 1867 gave.”12 American protectionism’s intentional complexity, as evidenced by the current antidumping law, persists to this day.

The Late 19th to Early 20th Century. Although the early years of American protectionism may have produced equivocal outcomes, several rigorous academic studies show that the inefficacy of U.S. trade barriers became more consistent and pronounced as the 19th century turned into the 20th. Such results stand in stark contrast to politicians’ and pundits’ continued insistence that the protectionism of that era caused, rather than merely coincided, with strong economic growth.

For example, while acknowledging questions about the economic effects of pre–Civil War protectionism, De Long found that protectionism in the post–Civil War period caused large and unequivocal harms to the U.S. economy. In particular, De Long found that “whatever Americans gained in faster mastery of technology as a result of protection in the late 19th century, they lost more because the higher price of—imported—capital goods made it more difficult and costly to build America’s transportation network and industrial base.” Further, he found that manufacturing tariffs “meant that the U.S. gave up the opportunity to export more high value-added agricultural products to Europe to boost its national income,” thus acting as a wealth transfer from Western farmers to Eastern industrialists. He concluded by rejecting outright the notion that post–Civil War tariffs, which lay heavily on capital goods needed for industrialization, were good for U.S. economic growth.13

Similarly, in a 2000 paper, Irwin reported that “(i) late nineteenth century growth hinged more on population expansion and capital accumulation than on productivity growth [driven by protectionism]; (ii) tariffs may have discouraged capital accumulation by raising the price of imported capital goods; (iii) productivity growth was most rapid in non-traded sectors (such as utilities and services) whose performance was not directly related to the tariff.”14 The last point warranted elaboration: “The mundane non-traded sectors, such as utilities, distribution, and other services, accumulated capital more rapidly than manufacturing, achieved higher rates of [Total Factor Productivity] growth than manufacturing, and boosted U.S.–U.K. relative labor productivity in such a way as to help the United States overtake the United Kingdom in per capita GDP. These non-traded sectors were a key feature of U.S. economic development during this period.” Irwin concludes that, contrary to conventional wisdom, trade protection was probably not a driver of late nineteenth 19th century U.S. economic growth. A separate study by Irwin bolstered this conclusion, finding that, while high 19th century tariffs on pig iron may have helped domestic producers, they harmed other manufacturers that relied on iron to produce machinery, bridges, and other downstream products. Moreover, 1890 tariffs on tinplate were not solely responsible for the industry’s development and imposed greater costs than benefits.15

The qualitative conclusions of Irwin’s 2000 paper were subsequently corroborated quantitatively by economist Yeo Joon Yoon. Applying a general equilibrium model focused on the postbellum U.S. economy, Yoon found that high manufacturing tariffs had an insignificant effect on U.S. growth, and that the single most important driver of growth between 1870 and 1930 was, by far, the expanding U.S. labor force. That demographic explosion accounted for almost half (47 percent) of all real GDP growth in the United States from 1870 to 1913.16

Smoot-Hawley. One of the most cited examples of American protectionism’s failures—the Smoot-Hawley tariff—might also be the most exaggerated, though the trade barriers did cause significant economic harms. Investigating Smoot-Hawley’s economic effects in his book Peddling Protectionism, Irwin found that the tariff slashed imports of dutiable goods and likely accounted for about one-third of the 40 percent reduction in U.S. imports between 1929 and 1932. The consensus among economists is that the tariff did not cause the Great Depression because its effect “was relatively minor in comparison to the powerful contractionary forces at work through the monetary and financial system”; but Smoot-Hawley made the Depression worse for the United States than it might otherwise have been, mainly by inciting protectionist retaliation against U.S. exports and creating a climate of economic nationalism around the world.17 On this last point, Irwin states:

Smoot-Hawley clearly inspired retaliatory moves against the United States, particularly—but not exclusively—by Canada. This retaliation had a significant effect in reducing U.S. exports. Even worse, Smoot-Hawley generated ill-will around the world and led to widespread discrimination against U.S. exports. Because discriminatory measures affect trade flows across countries more than non-discriminatory measures, U.S. exports were severely affected by them, and America’s share of world trade fell sharply in the early 1930s. Having helped poison international trade relations, the United States would spend the better part of the next two decades trying to dismantle the discriminatory trade blocs that had put U.S. exporters at such a significant disadvantage in major foreign markets.18

Others agree with Irwin’s general conclusions about Smoot-Hawley and the Great Depression but attribute more significant economic harms to the import protection. For example, in a 2003 quantitative assessment of the tariffs’ effect on the U.S. economy, New York Federal Reserve staff economists found that the tariffs were responsible for roughly 10 percent of the overall decline in economic output. Thus, “while the tariffs could directly account for only a small part of the Great Depression, they nonetheless had a significant, recession-sized impact, ‘small’ only in the context of the Great Depression.”19 Finally, it should be noted that some economists disagree, assigning far greater harms to Smoot-Hawley. George Mason University economist Thomas C. Rustici and colleagues, for example, argue that contemporary economic analyses dramatically understate the tariff’s harms because they ignore the impact of Smoot-Hawley on bank closings and the money supply. According to Rustici, Smoot-Hawley placed “enormous pressure on the central banking system and capital structure” and caused “the dramatic loss of export markets and declining farm income (due to foreign retaliation), rendering much agricultural capital useless.” This led to widespread agricultural bank failures, which created contagion effects. Trade uncertainty also crashed the secondary financial markets of each of the 10 largest world economies, creating “financial chaos.” As a result, the U.S. money supply dropped 29 percent between 1929 and 1933.20

Although Smoot-Hawley’s economic problems may be up for debate, its political ones are not. As Irwin summarized in Peddling Protectionism, the tariff bill “was a mass of private legislation carried out with little regard for national interest,” created by a political process that “gave congressional trade politics a deservedly bad name.” In particular, he noted the following:

By and large, the nation’s manufacturers were not clamoring for higher duties in 1928 or 1929, and the nation’s farmers, recognizing that higher import duties would have a limited effect on domestic prices, wanted some form of subsidy to relieve their financial woes. Refusing to consider subsidies, Republican politicians offered up a tariff in the hopes that it would placate farm interests and demonstrate that they were doing something to help agriculture. Once the door to a tariff change was opened, some groups—particularly small and medium-sized manufacturers—were only too happy to take up the offer and seek higher duties on imports for themselves. The process spun out of control and, as a result, the Smoot-Hawley tariff will forever be associated with logrolling, special interest politics, and inability of members of Congress to think beyond their own district. The episode illustrates that politicians are just as guilty as interest groups when it comes to using economic legislation to their benefit. The politicians were more interested in the appearance rather than the reality of helping farmers cope with low prices and high indebtedness.21

Given the economic and political harms, Irwin concluded that “the stigma of Smoot-Hawley is well deserved. It failed to achieve its domestic goal of helping farmers and it backfired against the United States around the world. It should always be remembered as a warning about the adverse consequences of poorly considered trade policies.”22

Unfortunately, it is not.

GATT to WTO

Following the failure of Smoot-Hawley, the imposition of the U.S. income tax, and World War II, the United States and much of the rest of the world began a period of gradual trade liberalization. In part, that was accomplished through the 1947 General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), the precursor to the World Trade Organization (WTO). In the United States, average tariffs on all imports dropped from 13.4 percent in 1942 to only 2.6 percent in 1995, when the WTO came into being.23 Nevertheless, U.S. protectionism did not disappear during this era; it just migrated into more discrete, hidden channels of administrative action, rather than taking the form of overt taxes levied by Congress.

The post-GATT, pre-WTO era offers us better analogies to the present: data and analyses are plentiful; trade was relatively developed and efficient; the multilateral trading system, anchored by GATT rules on tariffs and nondiscrimination, emerged; and tariffs were no longer the United States’ primary source of revenue. Furthermore, during much of this period, the U.S. government operated under the same general laws on trade negotiations and unilateral import restrictions as it does today. The latter category includes “trade remedy” laws addressing “unfair” product dumping and subsidization (the latter through “countervailing duties”), global safeguards against fairly traded import surges (“escape clause” relief), and foreign barriers to market access (“section 301”)—all of which will be discussed in this section and the next.

Numerous studies in the 1980s and early 1990s examined U.S. use of protectionism measures and are summarized here. The findings from these studies may be characterized as unequivocal. U.S. protectionism not only produced far higher total economic costs than benefits but also, more often than not, failed even to achieve its intended objective, whether that be the rejuvenation of an ailing American industry and its workforce or the opening of new U.S. export markets. In particular, we see the high economic costs, failed objectives, and empty successes.

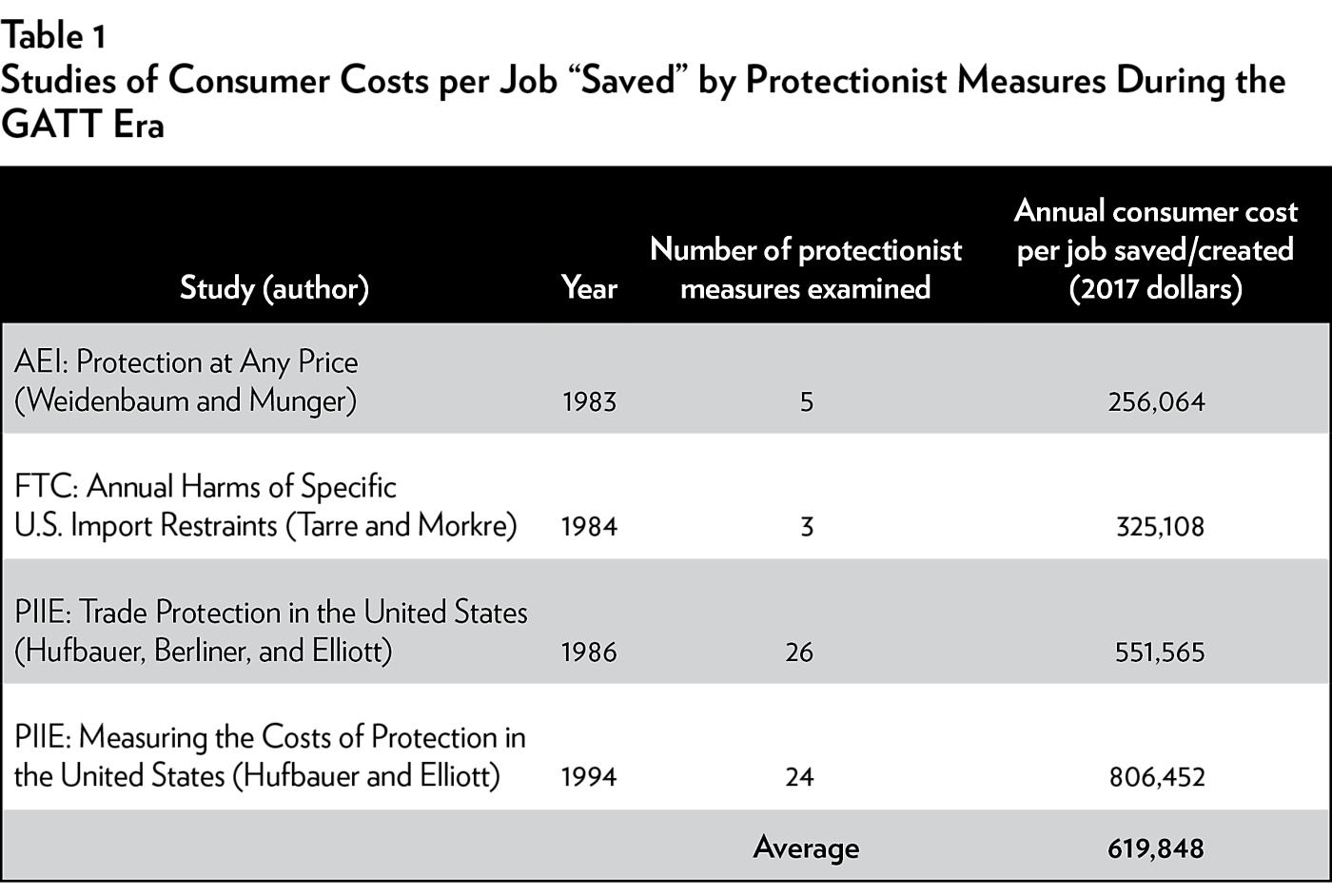

High Economic Costs. The American Enterprise Institute (AEI), the Peterson Institute for International Economics (PIIE), the U.S. Federal Trade Commission (FTC), and the Federal Reserve Bank of New York each studied specific U.S. import restrictions imposed between 1950 and 1990. They found that, on average, the measures annually cost U.S. consumers $620,000 (2017 dollars) per job supposedly saved in the industry at issue (see Table 1). By contrast, at the current hourly U.S. manufacturing wage of $20.69, a typical factory worker makes a little over $41,000 per year.

Failed Objectives. The PIIE studies also found that the protectionist measures at issue failed, in most cases, to prevent further increases in imports or declines in U.S. jobs; other studies during the period—from PIIE, the U.S. International Trade Commission (ITC), the U.S. Congressional Budget Office (CBO), and the Brookings Institution—found only one instance, the bicycle industry, in which protectionist measures actually resuscitated the industry in question. A separate PIIE analysis of section 301 of the U.S. Trade Act of 1974 found that U.S. attempts to open foreign markets through threats of unilateral retaliation failed more than half the time, with actual retaliation under the law even less effective.

Empty Successes. Indeed, even the most heralded example of American protectionist successes during this era—motorcycle safeguards that supposedly saved Harley-Davidson and the U.S.-Japan Semiconductor Trade Agreement—have been revealed through intensive examinations and contemporaneous reporting to have imposed immense costs on U.S. consumers and companies for very little, if any, actual gains.

Each of these factors is detailed in the following sections.

The High Economic Costs of Protectionism During the GATT Era

As noted, many studies of U.S. trade policy during the mid-20th century found that specific import barriers imposed massive costs on consumers and the economy more broadly, especially when compared to the jobs supposedly saved or created in the protected sectors at issue.

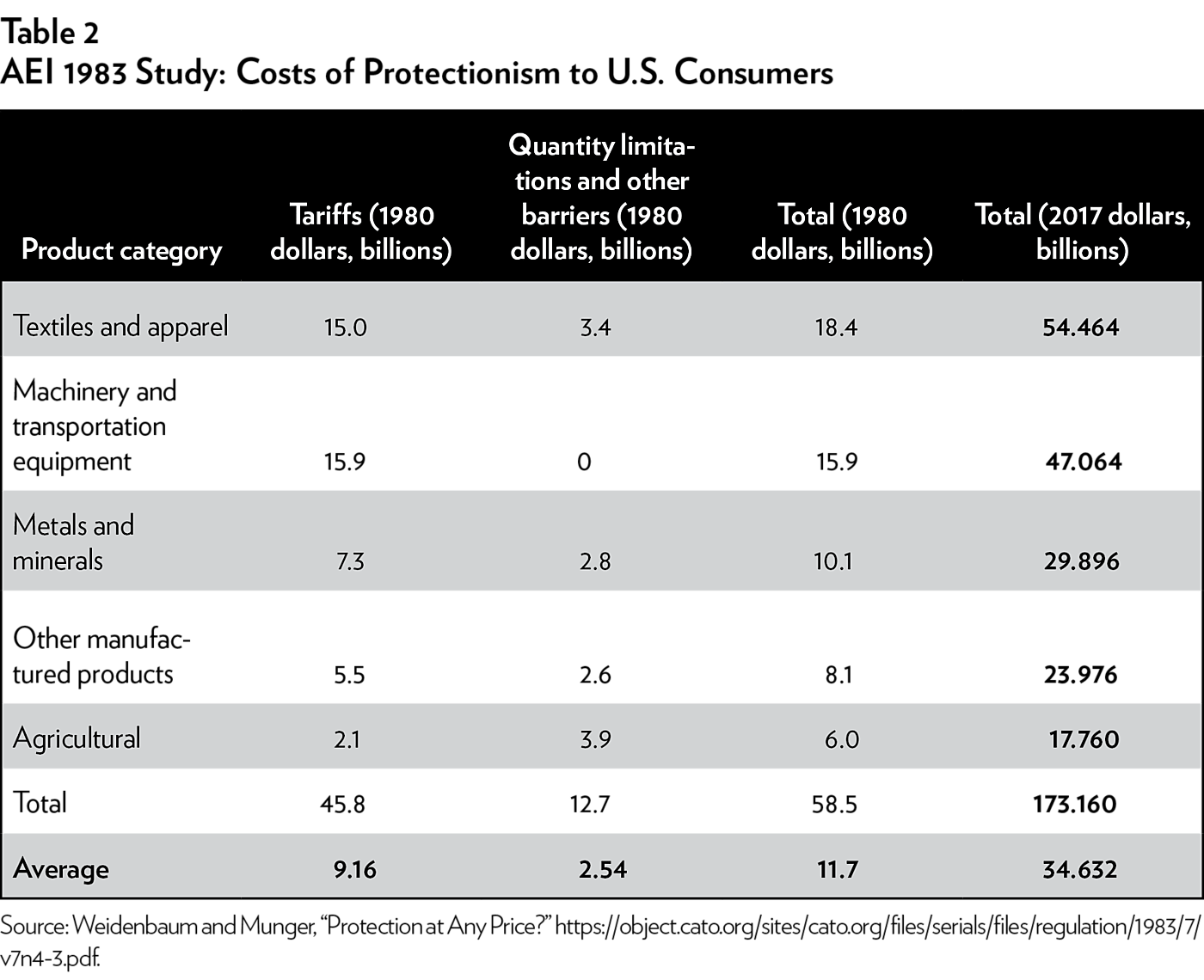

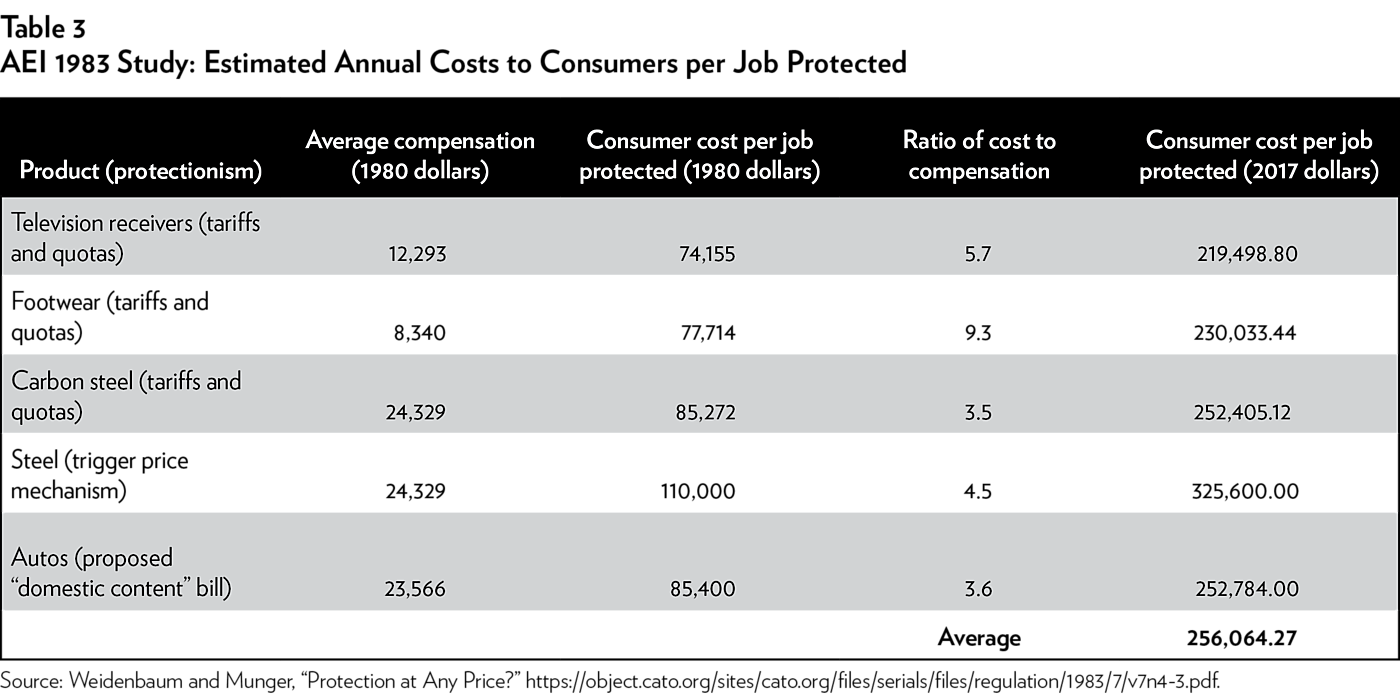

For example, the 1983 study by AEI’s Murray Weidenbaum and Michael Munger estimated that U.S. protectionism in five broad sectors—textile and apparel, machinery and transport equipment, metals and minerals, other manufactured products, and agriculture—imposed at least $58.5 billion ($173.2 billion in 2017 dollars) in direct costs on U.S. consumers in 1980. That amounts to “an implicit per-capita tax of $255 that year—or $1,020 for the average family of four—to protect a variety of domestic industries.” The authors surmise that these costs are conservative because they did not account for the protection’s innumerable “dynamic costs” to the economy in the form of decreased capacity, innovation, and productivity “that occur when firms are insulated from market forces.”24 The authors also calculated the costs borne by consumers to protect American jobs in specific industries, such as televisions, footwear, and steel. They found that the protectionist measures at issue annually inflicted between 3.6 and 9.3 times more costs on consumers per job supposedly “saved” by the protectionism than the actual compensation paid to the protected workers at issue. The details of the Weidenbaum-Munger study are shown in Tables 2 and 3.

Put simply, the protectionist measures in these five industries imposed financial costs on U.S. consumers that far exceeded any possible financial benefit to the protected workers at issue. Furthermore, “the difference between the compensation paid and the total implicit transfer from consumers goes partly to the owners of the protected firms and partly to sheer waste (because resources are used to produce goods domestically that could be produced more cheaply elsewhere).”25

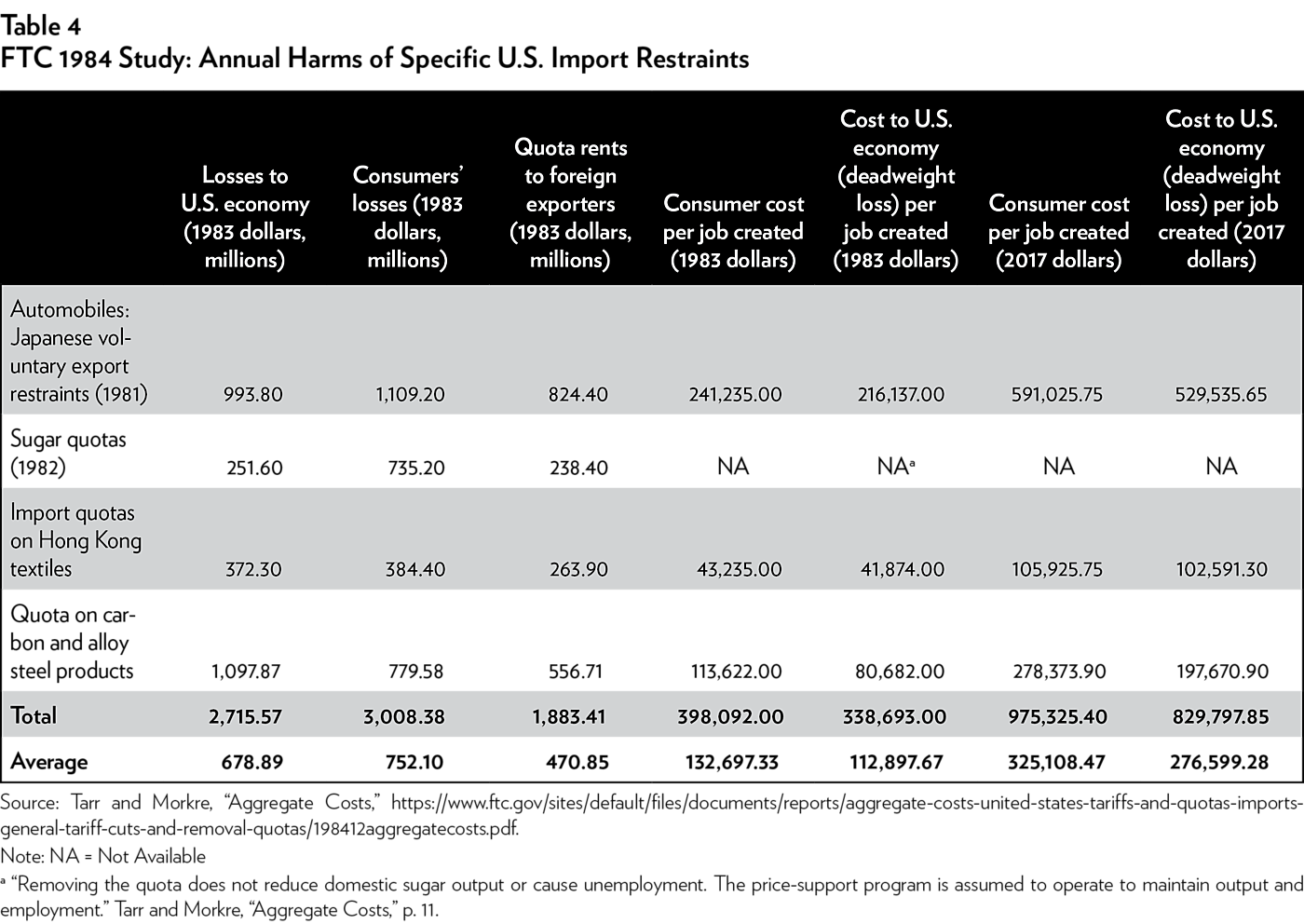

A 1984 study by the Federal Trade Commission found that the annual costs to the U.S. economy (i.e., consumer losses offset by domestic producer and government gains) from all tariffs plus quotas on automobiles, textiles, steel, and sugar amounted to $12.7 billion in 1983 dollars. The authors deemed this estimate “conservative” because, among other things, their analysis ignores the social and economic costs of rent seeking and does not identify all U.S. import quotas. The authors also found that, if these trade barriers were removed, the costs of adjustment (unemployment benefits for affected workers, idled capacity, etc.) would total approximately $760 million: thus, the cost of protectionism to the U.S. economy outweighed the cost of adjustment by 61 to 1. Even worse, the “[a]djustment costs are a one-time cost. The benefits to consumers and the economy continue year after year, however.”26 (See Table 4 for study details.)

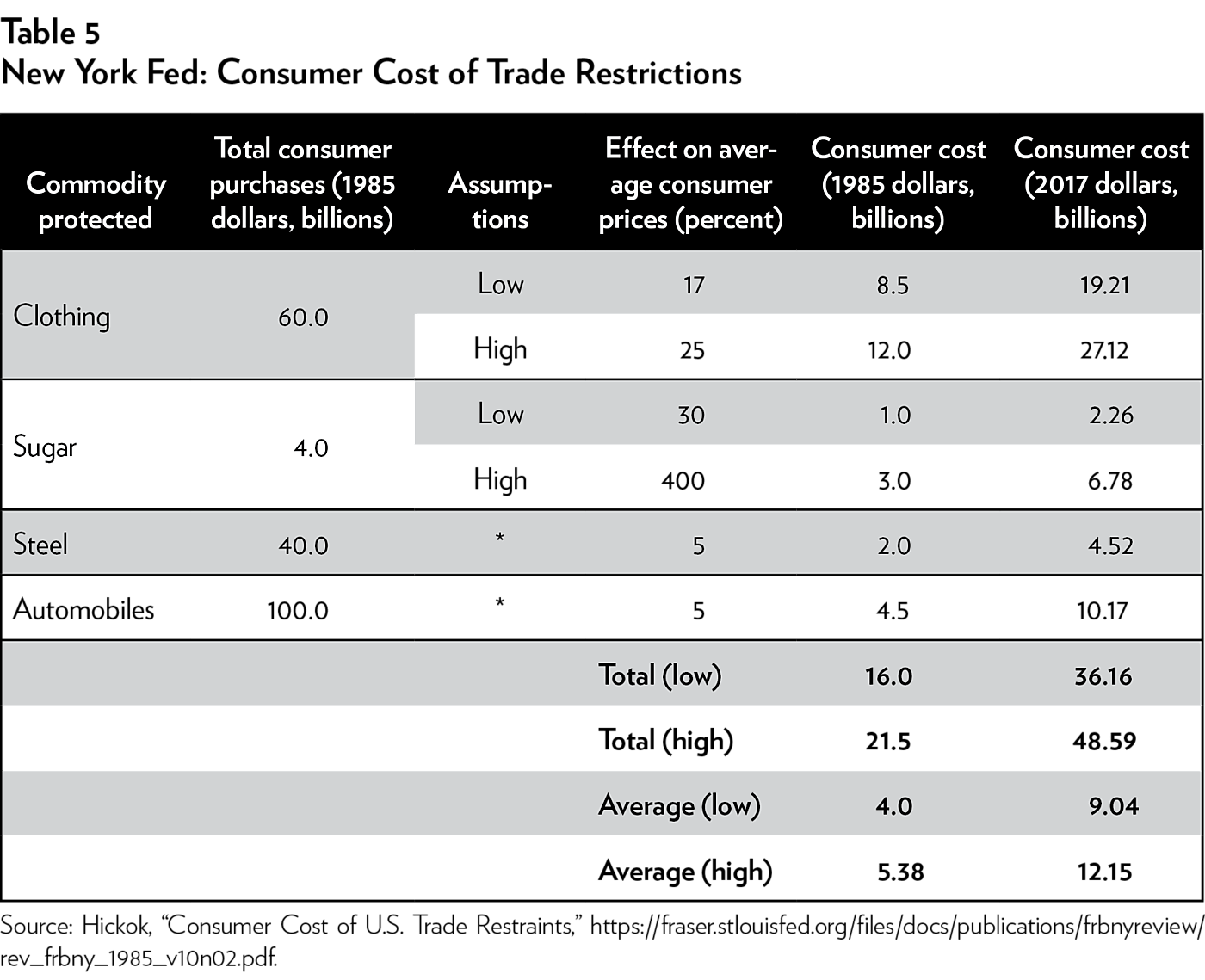

A 1985 New York Fed study came to similar conclusions, finding that, although the United States’ average tariff rate was only 4.4 percent on industrial products in 1984, U.S. trade restrictions on clothing, sugar, automobiles and steel forced U.S. consumers to spend $16 billion (1985 dollars) more on those products that year. (See Table 5.)

Perhaps even more distressing than this high overall cost, however, was the restrictions’ regressive income distribution effect. The effective price increases on clothing, sugar, and automobiles caused by the import restraints were conservatively calculated as generating the equivalent of a 23 percent “income tax surcharge” (i.e., a tax added to the normal income tax) for the lowest income (under $10,000/year) American families in 1984. And this tax gradually decreased as family incomes increased, ultimately resulting in a meager 3 percent surcharge for the richest American families (over $60,000/year).27

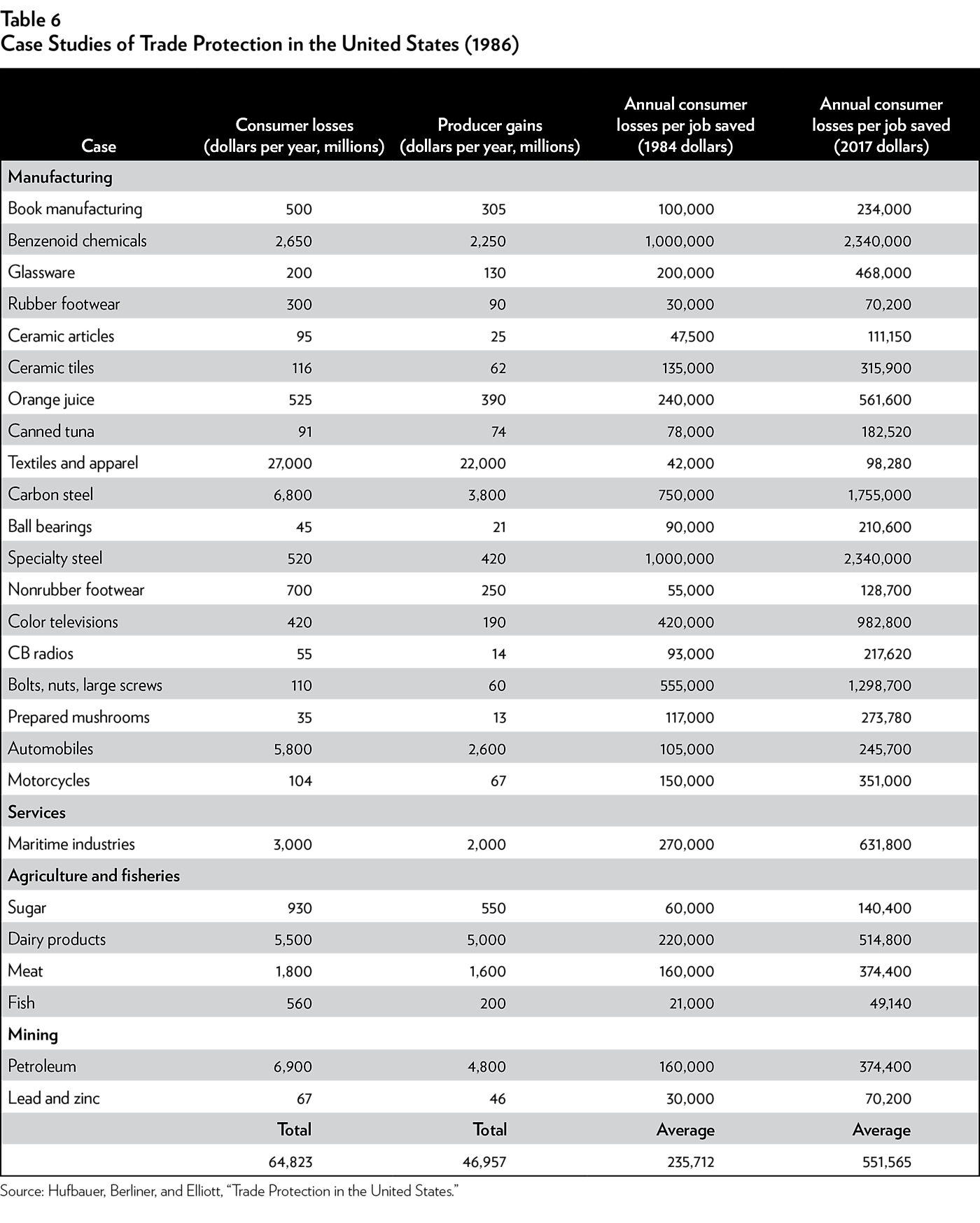

A 1986 PIIE study by Gary Hufbauer, Diane Berliner, and Kimberly Ann Elliott examined 31 cases of U.S. protectionist measures—including antidumping and countervailing duty actions, safeguards, quotas, and “voluntary” restraints—against specific imports.28 The study found that in 1984, total annual consumer losses topped $100 million (1984 dollars) in all but 6 of the 26 cases that permitted conclusive analysis. (See Table 6.) The most significant losses resulted from textile and apparel protection, while smaller but still significant losses were found for carbon steel, automobiles, and dairy products. Most of the protectionist rents accrued to domestic producers, though in some cases preferred foreign exporters also benefited. Furthermore, although the protectionist measures may have saved some jobs in the industries, these “savings” came at a huge cost: in 18 of 31 cases, the annual consumer cost per-job-saved was $100,000 or more. These costs exceeded $500,000 (1984 dollars) per job in benzenoid chemicals; carbon steel; specialty steel; and bolts, nuts, and screws. As tabulated in 2016 by AEI economist Mark Perry, these costs more than doubled in terms of 2016 dollars, with protection costing well over $2 million per job in some cases.29

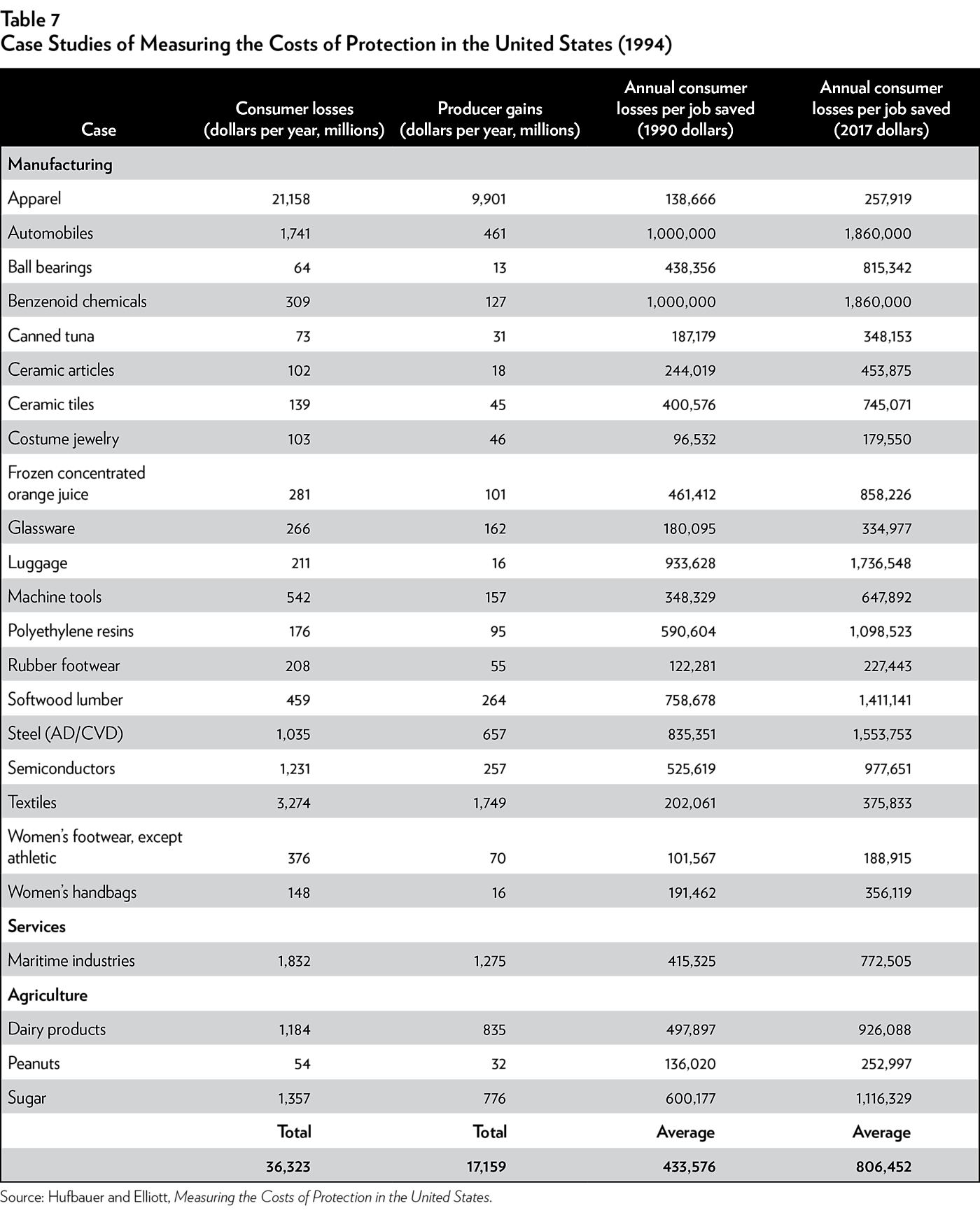

Hufbauer and Elliott revisited and updated their analysis in 1994, finding similar results.30 In particular, they calculated that the potential consumer gains from eliminating all U.S. import restrictions would total approximately $70 billion—around 1.3 percent of U.S. GDP in 1990. Put another way, import restrictions were harming the U.S. economy to the tune of $70 billion, almost half of which ($32 billion) was due to consumer losses in the 21 sectors that benefited from especially high protection—sectors that accounted for less than 5 percent of domestic consumption and 1.5 percent of total U.S. employment in 1990. By contrast, producers in these sectors gained about $16 billion in benefits from protection, while the government gained another $6 billion in tariff revenue. As a result, the “net national welfare gain from liberalization in these sectors amounts to an estimated $10 billion” (in 1990 dollars). As with the 1986 version of their study, Hufbauer and Elliott found consumer losses topping $100 million in all but three of the highlighted sectors, with annual consumer losses per job saved exceeding $200,000 per job in all but six sectors. In 2017 dollars, such losses again almost double, often topping $500,000 per job saved and even exceeding $1.5 million per job in several cases. (See Table 7.)

Regardless of the author, the trade measure, or the time period examined, these studies all found the same results of American protectionism: high consumer costs that far outweighed benefits to protected producers and workers. As summarized by the St. Louis Fed in 1988:

The empirical evidence is clear-cut. The costs of protectionist trade policies far exceed the benefits. The losses suffered by consumers exceed the gains reaped by domestic producers and government. Low-income consumers are relatively more adversely affected than high-income consumers. Not only are there inefficiencies associated with excessive domestic production and restricted consumption, but there are costs associated with the enforcement of the protectionist legislation and attempts to influence trade policy.31

The Failed Objectives of Protectionism During the GATT Era

Beyond the harms to U.S. consumers and the economy overall, American protectionism often failed to achieve its intended objectives, whether halting imports, boosting jobs, helping a beleaguered industry recover and thrive, or opening protected foreign markets.

Import Penetration and Jobs. Of the 21 protected U.S. industries examined in the aforementioned 1994 PIIE study, only 2 (softwood lumber and sugar) actually saw declining imports during the years in which they received import protection. These 21 industries faced, on average, a 9.4 percent annual increase in imports over the periods examined.32 Furthermore, only 6 of the 21 industries (ball bearings, benzenoid chemicals, ceramic tiles, frozen concentrated orange juice, polyethylene resins, and dairy products) experienced an increase in domestic employment; overall annual employment in these industries actually declined by 1.14 percent each year. The authors therefore concluded that “[d]espite the import-dampening effects of the trade barriers in these sectors, the value of imports tends to continue increasing, while employment usually declines on average.”

Protectionism during this period, therefore, not only imposed large costs on the U.S. economy but also did not stem import penetration or job losses in the overwhelming majority of the industries examined. These findings were consistent with the authors’ previous work on protectionism, in which they concluded:

Special protection as practiced in the United States cannot, for the most part, be faulted for freezing the status quo. Instead, it should be criticized for providing rather little assistance to workers and firms that depart the troubled industry; for imposing huge costs on consumers; for not promoting a smooth transition to the realities of international competition; and for engendering widespread opposition to trade liberalization.33

Industrial Revival. Import protection also proved incapable of helping protected firms adjust and thrive during the GATT period. For example, a 1982 U.S. ITC study assessed whether import relief—in particular, “escape clause” safeguards on fairly traded imports—affected adjustment in the five largest U.S. industries that both experienced import injury and received protection prior to 1975: bicycles, sheet glass, stainless steel flatware, watches, and carpets. The report concluded that only one of these industries—bicycles—modernized its production, improved its performance, and became more competitive with imports after receiving escape clause relief from import competition. For three industries—carpets, flatware, and sheet glass—protection was an unequivocal failure: all three experienced “contraction,” with shipments, employment, and capital stock all lower in 1977–80 than during the period before they received import protection (1955–61). (The results for one industry—watches—were inconclusive because of product variation and contemporaneous changes in the market. But the ITC nevertheless concluded that any possible benefits from protection were small and that “contraction predominated because only one of the seven firms supporting the petition stayed in the industry.”) Furthermore, the ITC found that many nontrade factors, such as competition from new domestic substitutes, caused much of the injury experienced by the protected industries. As a result, the ITC concluded that import protection simply “slowed the decline of the contracting industries,” rather than helping them adjust and subsequently flourish.34

Other contemporaneous studies came to similar conclusions. A 1986 report from the CBO considered the effects of trade protection in revitalizing domestic firms in four cases—textiles and apparel, steel, footwear, and automobiles—between the 1950s and 1970s. The authors found that, indeed, U.S. trade barriers limited imports and increased protected firms’ output, employment, and profits above what they would have been without protection. However, “[i]n none of the cases studied was protection sufficient to revitalize the affected industry.” The steel, footwear, and textile and apparel industries repeatedly sought new import protection after their previous protection expired, and the automobile industry succumbed to imports of the small cars that were the source of their “competitive difficulties.” Furthermore, the protection did not significantly increase the companies’ incentive to invest in cost-saving technologies that would improve their long-term competitiveness—even when the protected companies had the capital available to make such investments. The authors concluded that, because the system of trade restraints was unable to save protected industries, the U.S. government should consider policies other than import protection—such as encouraging investment in less labor intensive industries, aiding displaced workers, or ending “special treatment for trade-impacted industries”—when crafting new U.S. trade policies.35

In 1986, Robert Lawrence and Paula DeMasi examined the effect of escape clause relief (tariffs, quotas, or “orderly marketing arrangements”) on 16 U.S. manufacturing industries, representing nearly all industries that secured such protection between 1950 and 1983.36 The results were damning: only 1 of the 16 industries—again, the bicycle industry—expanded after the protection lapsed, 11 contracted, and the remaining 4 were inconclusive at the time. Furthermore, 8 of the 12 industries whose “temporary” escape clause relief had expired actually went back to the government for more protection. Even the “successful” bicycle industry experienced serious disruption, particularly for workers: each of the three largest bicycle manufacturers closed its plant and moved to other states in the 1950s; and of the four unionized companies, two closed plants in 1956, and the remaining two closed plants in the 1970s.37 Thus, the bicycle industry may have benefited from import protection, but many workers in the industry certainly did not.

A subsequent Brookings Institution survey from Lawrence and Robert Litan reiterated these findings and came to similar conclusions in new cases of U.S. government protection for the domestic textile, television, and automobile industries. In the latter two cases, the authors found that import protection may have contributed to the domestic industry’s decline. For example, voluntary export restraints on Japanese automobiles strengthened American producers’ domestic market power and induced them to raise prices. This, in turn, reduced domestic demand for both cars and labor, and thus actually reduced U.S. automobile employment in 1983 by 31,000.38 Other industry-specific studies came up with similar results. With respect to televisions, a 2016 Quartz report showed how U.S. trade barriers not only strengthened competitors in Taiwan and Korea, but also undermined American television tube manufacturers and diverted investment away from the flat panel displays that would later come to dominate the television industry.39 A 1987 study from Robert Crandall on “The Effects of U.S. Trade Protection for Autos and Steel” found that this protection limited imports but actually harmed the industries’ long-term position. For example, it discouraged improvements in product quality and encouraged cannibalistic overinvestment and too-rich labor contracts that “simply postpone[d] part of the necessary adjustment to the loss of competitiveness.” As a result, Crandall concluded, “The experience with the auto and steel industries raises serious questions about the effectiveness of quotas as a means to revitalize an industry.”40

Indeed, even the supposed “success stories” of 1980s protectionism—Harley-Davidson motorcycles and U.S. semiconductors—were anything but: Harley’s revival had little to do with protection from Japanese motorcycle imports, and the U.S.-Japan semiconductor agreement failed to encourage new production or investment. Both episodes also produced the typical consumer harms.

Motorcycles. The 1983–87 escape clause safeguard, which established maximum tariffs of 45 percent on heavyweight motorcycle imports, is credited with saving Harley-Davidson and even today serves as an example of American protectionist success. Subsequent analyses and contemporaneous reporting, however, tell a much different story—one of consumer pain and very little actual gain to Harley. For example, the aforementioned 1986 PIIE analysis of U.S. trade barriers found that the tariffs imposed significant economic harms. Because of higher prices, U.S. consumers paid approximately $150,000 ($351,000 in 2017 dollars) per U.S. motorcycle manufacturing job allegedly saved by the tariffs in 1984. Thus, even assuming the tariffs saved U.S. jobs (an unlikely assumption, as shown next), they cost a small fortune to do so.

Even more damning, however, is the fact that the tariffs played a very small role, if any, in Harley’s resurgence. First, import competition had weakened even before the tariffs were imposed—Harley made large bikes with 1000cc and 1300cc engines, while Japanese competitors (the main target of the safeguard) focused on smaller motorcycles with engines under 1000cc. Second, the targeted Japanese exporters easily avoided the new tariffs. Because only motorcycles with 700cc engines or larger were affected by the tariffs, Japanese manufacturers Honda, Suzuki, and Yamaha just developed, produced, and shipped motorcycles with engines between 695cc and 699cc. Kawasaki escaped the tariffs by shifting more assembly activities to its U.S. plant.41 Third, the United States exempted motorcycles from Germany, Italy, the United Kingdom and elsewhere, thus permitting brands from those countries to compete freely in the U.S. market.42 Finally, contemporaneous reporting from the 1980s showed that a complete overhaul of Harley-Davidson’s management, manufacturing, and marketing policies—not tariffs—was responsible for the company’s resurgence.43 The overhaul included, ironically, Harley’s adoption of Japanese manufacturing techniques.

U.S. motorcycle sales data from 1983 to 1987 demonstrate the futility of the import protection that supposedly saved Harley-Davidson. Harley’s annual sales of motorcycles below 1100cc (i.e., the types covered by the tariffs) averaged 27.89 percent of the company’s total sales in 1983 and about the same share, 27.58 percent, in 1987. Japanese firms, by contrast, shifted sales to smaller motorcycles: 700–1099cc models dropped from a 53.98 percent share of their 1983 sales to below 28 percent in 1984–87, while their annual sales of 450–699cc models increased from 43.38 percent of total sales in 1983 to over 60 percent from 1984–87.44 These and similar data led economists Taiju Kitano and Hiroshi Ohashi to conclude that “the safeguard provided by the U.S. government until 1987 explains merely 6 percent of Harley-Davidson’s sales recovery.” The main reason was that the tariff increases did little to shift American consumers from Japanese motorcycles to Harleys—something that any serious hog rider in America probably could have told you without the fancy analysis.

Semiconductors. The 1986 Semiconductor Trade Agreement (STA) between the United States and Japan has also been lauded as an example of the virtues of American protectionism and managed trade. It too, however, has been oversold. Under the STA, the Japanese government agreed to stop its producers from “dumping” dynamic random-access memory (DRAM) and erasable programmable read-only memory (EPROM) chips—enforced through production limits and export restraints that kept chip prices above U.S.-determined levels—and to guarantee foreign producers 20 percent of the Japanese market. In exchange, the United States suspended ongoing antidumping and section 301 investigations of Japanese memory chips.45

The STA’s economic harms were significant. The 1994 PIIE analysis of import barriers found that, in 1989, the STA generated a net national welfare loss of $974 million ($1.81 billion in 2017 dollars) and cost U.S. consumers over $525,000 ($977,651 in 2017 dollars) per manufacturing job potentially saved. After the STA took effect, domestic semiconductor prices “skyrocketed,”46 and a “full-fledged shortage of DRAMs was widely felt in the United States and Europe by early 1988.”47 As a result, U.S. semiconductor users, particularly up-and-coming computer manufacturers like Apple that were dependent on DRAMs, were crippled; they were less able to compete with Asian and European makers of IBM “clones” because those manufacturers could obtain cheaper DRAMs.48 The computer manufacturing industry was hurt so badly that it actually shed one job for every U.S. semiconductor job supposedly gained from the STA.49 For American consumers, the increase in the price of DRAMs added up to almost $100 for a personal computer selling for $600 or $700 in 1988.50

At the same time, the biggest beneficiary of the STA was not U.S. semiconductor manufacturers (though two players did enjoy extra profits). Rather, it was Japanese producers who, because of the STA, charged much higher prices for semiconductors in both the United States and elsewhere. According to one Brookings Institution study, Japan’s manufacturers earned $1.2 billion in extra DRAM profits in 1988 alone and another $3–4 billion on all products in 1989—most of which was paid by U.S. consumers and computer manufacturers.51 Other studies found similar gains for Japanese producers, in part because of collusive behavior among them.52

By contrast, U.S. producers, even as they benefited from artificially high prices and U.S. government subsidies,53 did not increase production capacity.54 All but one U.S. chipmaker left the DRAM market within a decade. And the STA prevented neither industry recessions (1989–91 sales were “extremely weak”) nor declining U.S. market shares (which shrunk from 83 percent to 70 percent between 1986 and 1992).55 One reason is that U.S. firms found ways to avoid the STA by importing not individual EPROMs and DRAMs but rather assembled circuit boards that weren’t subject to the deal.56 As a result, “[f]or most U.S. chip makers, the main impact of the price hikes was vastly greater profits strengthening their Japanese competitors.”57 Longer term, the STA actually helped “accelerate the entrance of Korean companies onto the world DRAM scene as with Japanese companies, the supernormal profits that were obtainable in the years immediately after the [STA] allowed Korean firms such as Hyundai, Samsung, and LG to reap unexpected returns and gain a foothold at the lower end of the semiconductor technology ladder.”58 Those companies still thrive today in the global semiconductor market.

Indeed, even the much-heralded Japanese market share targets were not the success that some now proclaim. For example, although foreign semiconductor exports to Japan in 1992 did hit the 20 percent market share targets set forth in the STA, economist Craig Parsons found that this “achievement” was caused by broader macroeconomic trends, not the agreement itself.59 Other reports at the time noted that Japanese firms achieved the target by dumping the semiconductors they were forced to buy into Tokyo Bay.60 Overall, “there is little consensus on whether the STA was effective in increasing the foreign market share.”61

Finally, the STA had significant political ramifications at home and abroad. It encouraged collusion among Japanese producers and restored the Japanese government’s control over the sector, with U.S. help. It led to the creation of a new and powerful lobbying group in the United States—composed of injured downstream user industries—that would go on to mold U.S. trade policy to their own ends.62 It also demonstrated, once again, the folly of U.S. industrial policy: a 1987 U.S. Department of Defense report, for example, argued that DRAMs were central to the future of U.S. global technology leadership, and that the loss of DRAM capacity would destroy U.S. firms’ ability to compete in other high-tech sectors. Other industrial policy fans predicted that the STA would encourage new U.S. entrants in the DRAM market. Neither prediction proved accurate. Motorola purchased prefabricated semiconductor dies from Toshiba, assembled them in Malaysia, and imported them under Motorola’s name to avoid duties; U.S. Memories, a consortium to expand domestic DRAM production, was “stillborn and collapsed in January 1990 owing to insufficient financial support and an unwillingness of other major buyers … to commit to future purchases.”63 Indeed, American companies were actually exiting the DRAM market, having already discerned that their future was not in the “high-volume, low-profit commodity” but in advanced microprocessors, specialty chips, and design.64 Government policymakers foresaw none of this.65

As I will discuss in the next section, other U.S. high-tech industries benefiting from similar import protection and industrial policies—such as flat panel displays and supercomputers—suffered similar fates.

Market Opening and Section 301. Finally, protectionism—or the threat thereof—proved relatively ineffective in opening foreign markets to U.S. exports during this era, even though the World Trade Organization did not yet exist to provide an external check on American (or other countries’) unilateralism. The clearest example of this inefficacy is U.S. actions under section 301 of the Trade Act of 1974. At the time, section 301 gave the United States almost unlimited discretion to retaliate unilaterally against foreign countries where the rights of the United States under any trade agreement were being denied, or a foreign government act, policy, or practice contradicts any trade agreement or “is unjustifiable and burdens or restricts United States commerce.” The U.S. experience with section 301, which fell into disuse upon the advent of the WTO dispute settlement system, is particularly valuable in light of Trump administration statements that, given the law’s successes during the Reagan administration, they might revive it.

That experience, however, should caution against a return to the Reagan-era policy of reciprocity and retaliation. In a comprehensive analysis of every section 301 investigation between 1975 and 1994—91 cases targeting foreign actions against U.S. goods, farm products, services, and intellectual property—Thomas Bayard and Kimberly Ann Elliott found that section 301 produced, at best, mixed results in terms of achieving its ultimate objective of removing the targeted foreign trade barrier. Of the 72 cases that permitted analysis, the authors found that U.S. negotiating objectives were “successful” less than half the time (35 cases, or a 48.6 percent “success ratio”). The successes occurred most often when the targeted country was dependent on the U.S. market for its exports (something which is less likely today due to the diversity of global economic growth) and during a small window of time between 1985 and the passage of the 1988 Trade Act, which remains in force today. By contrast, the United States has won more than 85 percent of the disputes it has litigated at the WTO since 1995, achieving compliance in almost all of those,66 and has favorably settled many other WTO complaints before litigation began.67

Furthermore, Bayard and Elliott’s definition of “success” in section 301 cases was rather kind to U.S. negotiators: “success” did not require the complete removal of the trade barriers at issue and an actual increase in American exports; it meant, simply, cases in which “U.S. negotiating objectives—that is, improved market access for U.S. exporters of goods and services, reduced export subsidies … and improved protection for intellectual property rights (IPR)—were at least partially achieved.”68 Thus, cases such as those of Japanese leather quotas—which did not remove the quotas but resulted in lower Japanese tariffs on other U.S. exports—were counted as a “partial success.”69 Furthermore, “success” could mean new access for specific firms but not actual liberalization of the targeted market as a whole. Thus, “market shares may only have been reallocated to benefit U.S. firms at the expense of third parties. In such cases, the result might not be considered a success for U.S. trade policy more broadly defined.”70 Perhaps for this reason, the authors generously concluded that all section 301 actions combined may have increased U.S. exports by only 1 percent annually.71 Finally, the authors passed no judgment on the value of the U.S. negotiating objectives at issue. Thus, a “success” in their analysis could include the partial “achievement” of questionable trade objectives (e.g., those under the STA), which resulted in no actual trade liberalization overall. Most people would hardly call that a real success.

More damning for today’s supporters of American trade unilateralism, however, was the U.S. record of retaliation under section 301. Of the 12 cases examined in which the United States imposed some form of unilateral retaliation (tariffs, suspension of preferential access, etc.) under section 301, the authors deemed only 2 “successes”; the other 10 involved failures. Retaliation under section 301 was therefore associated with the achievement of U.S. negotiating objectives only 17 percent of the time it was used.72 Perhaps more important, American “unilateralism” was not very “unilateral” at all; instead, it was almost always in concert with multilateral trade rules under the GATT. “There were only five cases potentially subject to GATT rules that provoked U.S. moves toward retaliation in the absence of GATT dispute settlement procedures.”73 Use of the GATT, moreover, was a successful strategy. “In every case where a GATT panel found a violation or evidence of nullification and impairment, changes in the offending policy were made.”74 For this and other reasons, the authors found that, despite the “successes” of section 301 unilateralism during the Reagan years, that period cannot serve as a “good predictor” of its efficacy in the WTO era. The far broader and more precise trade rules and successful, binding dispute settlement system of the WTO stand in stark contrast to the earlier GATT period.75

WTO Era

Since the advent of the World Trade Organization in 1995, American unilateral protectionism has further retreated, relegated to relatively few trade barriers on politically sensitive goods and services dating back decades (even to Smoot-Hawley) and narrow administrative actions under U.S. “trade remedy” laws (i.e., the antidumping, countervailing duty, and safeguard laws). The results of this remaining protectionism, however, are no better than the results experienced during the previous eras discussed. Arguably, the costs are much higher because U.S. participation in the WTO and further integration of the U.S. and global economies have created tangible ramifications (i.e., new prospects of retaliation and greater harms to import-dependent U.S. companies) for protectionism that did not exist in the pre-WTO periods. Macroeconomic studies of U.S. protectionism continue to show that it imposes significant harms on American consumers and the broader economy. Examinations of trade remedies in specific sectors—steel, high-tech goods, softwood lumber, paper, and tires—again show massive consumer costs and the failure to revive the companies seeking protection. The U.S. antidumping law, including measures against Chinese imports, also has repeatedly been found not only to hurt U.S. consumers and many large American exporters but also to improve only rarely the state of the protected industry. Instead, what often lies in the wake of this protection is the bankruptcy of the very firms that lobbied for it. Other nontariff barriers, such as those on meat labeling, sugar, and maritime shipping, have proven no better, and many cases have led to foreign retaliation or the threat thereof.

The Same Old Problems. Although more limited than in previous periods, U.S. barriers to imported goods and services continue to impose significant harms on consumers and the economy more broadly. These harms have been tracked over the last 20 years in periodic reports from the U.S. ITC. The reports have consistently found that barriers to the importation of goods and services are a net drag on the economy. In the most recent report (December 2013), the ITC found that, although the U.S. economy was relatively open, “significant restraints on trade remain in certain sectors,” such as cheese, sugar, canned tuna, textiles and apparel, and certain “high-tariff manufacturing sectors.”76 It is no coincidence that many of the same import barriers highlighted in the ITC report were examined during earlier periods. Protectionism, like any government program, is often difficult to terminate and can persist for decades despite a long record of failure.

Removal of these restraints, the ITC found, would increase U.S. economic welfare by $1.13 billion per year, while imports and exports would expand by about $6.2 billion annually. The highest-cost import barriers in the report were sugar tariff rate quotas ($276.6 million per year), textile and apparel tariffs ($483.4 million), cigarette tariffs ($139.5 million), and footwear and leather product tariffs ($114.8 million). Unsurprisingly, the biggest beneficiaries of any such liberalization (i.e., the groups now bearing the costs of the current regime) would be U.S. consumers: “Consumers benefit because they can continue to buy the same quantity of the good at a lower price and have money remaining for other uses. Producers who use the product as an input become more competitive in both domestic and foreign markets.”77 A 2006 study from the Department of Commerce made the same point with respect to the consumer pain of sugar tariff rate quotas; it found that each job saved in the highly protected sugar production industry cost the U.S. economy over $800,000 and caused three confectionery manufacturing jobs to disappear.78

Importantly, the ITC’s analysis does not quantify either import restraints for services or those resulting from trade remedies or other administrative import restrictions. The report does make note of services barriers and qualitatively assesses U.S. restrictions on commercial banking, telecommunications, shipping (primarily the Jones Act), and air transport services. Other studies have found that service barriers—just as with goods (which have been examined a great deal more)—impose high costs without providing significant benefits to the protected sectors. Most notably, the Jones Act has been found to increase U.S. shipping and energy costs; hurt water-bound U.S. markets, such as Puerto Rico, Alaska, and Hawaii; inhibit the quick resolution of national emergencies, such as the Deepwater Horizon spill; and actually undermine American shipping capabilities.79

The ITC report also ignores administrative protectionism like trade remedies; this is not a mistake but rather at the direct instruction of the U.S. Trade Representative,80 which is a good indication of the political import such measures have under current U.S. trade policy. Fortunately, as shown in the next sections, others have sought to examine these measures—to quantify their benefits and (mainly) their costs.

For example, in his book High-Tech Protectionism, AEI’s Claude Barfield examined the effects of U.S. antidumping actions in four industries: supercomputers, flat-panel displays (FPDs), semiconductors, and steel. His conclusions will sound familiar. The harms imposed by the semiconductor cases have already been addressed, but it is important to note that, despite (or perhaps because of) the failure of the Semiconductor Trade Agreement, one U.S. semiconductor producer continued to seek DRAM import protection through the U.S. antidumping law into the early 2000s, without much success. As Barfield noted, “Any economic analysis of the competitive realities of the worldwide semiconductor industry in the late 1990s—whether conducted as a part of a sunset review or for de novo antidumping proceedings—would lead directly to the conclusion not only that this particular antidumping duty order was unwarranted but also that the entire rationale behind antidumping actions for this industry is flawed and inevitably results in a reduction of world economic welfare.”81

Antidumping duties on FPDs produced similar unintended consequences. The 63 percent duties on imported FPDs from Japan caused the domestic price of computers to spike, with Compaq estimating that “the duty added $1,000 to the cost of building a computer in the United States.” Even worse, the duties “impelled both U.S. and Japanese companies to move out of the United States, causing job losses at a number of sites in this country.” Compaq moved to Scotland; Toshiba stopped building laptops at its American plant; Apple moved production to Ireland; Sharp moved to Canada; and IBM moved several of its assembly operations to offshore locations. Meanwhile, the United States never did establish a healthy FPD industry, even with generous government research and development subsidies and hollow-yet-familiar warnings that FPDs were the key to U.S. high-tech dominance.82 High antidumping duties imposed in 1996 on supercomputers similarly failed: duties targeted “vector” computers at the precise moment that such products were sliding into oblivion (losing out to nonvector computers), and the competition between Cray and Japan’s NEC—the two main players in the antidumping case—was ending due to industry consolidation and new market entrants like Sun Microsystems.83

Another industry to note is softwood lumber. The 1996 U.S.-Canada Softwood Lumber Agreement (SLA)84 suspended a U.S. countervailing duty investigation of Canadian lumber and, in exchange, imposed producer-specific import quotas and special fees for any imports above those levels. According to a 2000 Cato Institute analysis, the deal increased U.S. lumber prices by $50 to $80 per thousand board feet. As a result of these increased construction costs, the price of a new home in the United States increased by $800 to $1,300, thus pricing approximately 300,000 American families out of the housing market. The SLA also hurt major U.S. lumber-using companies (particularly construction firms and retailers like Home Depot), even though workers in such companies outnumbered U.S. logging and sawmill workers by more than 25 to 1.85 And, as with other forms of protection, the SLA neither solved the longstanding U.S.-Canada lumber dispute (which dates back to the 1980s) nor restored the U.S. industry. When the most recent SLA expired in 2016, the industry immediately petitioned for new import protection. At the same time, the logging and wood products industries’ workforce continued to shrink, going from approximately 660,000 workers in 1996 (80,000 logging, 580,000 wood products) to under 450,000 today (51,000 logging, 392,000 wood products).86

No U.S. industry has benefited more from protection than the steel industry. In the 1990s and early 2000s, for example, approximately 150 steel antidumping orders were in place, covering almost 80 percent of all steel imports during the period. The industry also received protection against global imports through the George W. Bush administration’s 2001 imposition of global safeguard tariffs ranging from 8 percent to 30 percent on a wide range of steel products. As with other bouts of protectionism, the costs of these actions were massive, while gains were minimal. Estimates of the economic costs of U.S. trade remedy protection against steel imports range from approximately $60 million per year to well over $2.7 billion—or $450,000 per job saved in 2001 ($596,000 in 2017 dollars). And given that U.S. steel-consuming industries employ between 40 and 60 workers for every 1 steelworker, every job allegedly saved in the steel industry was far outnumbered by job losses in steel-using industries.87

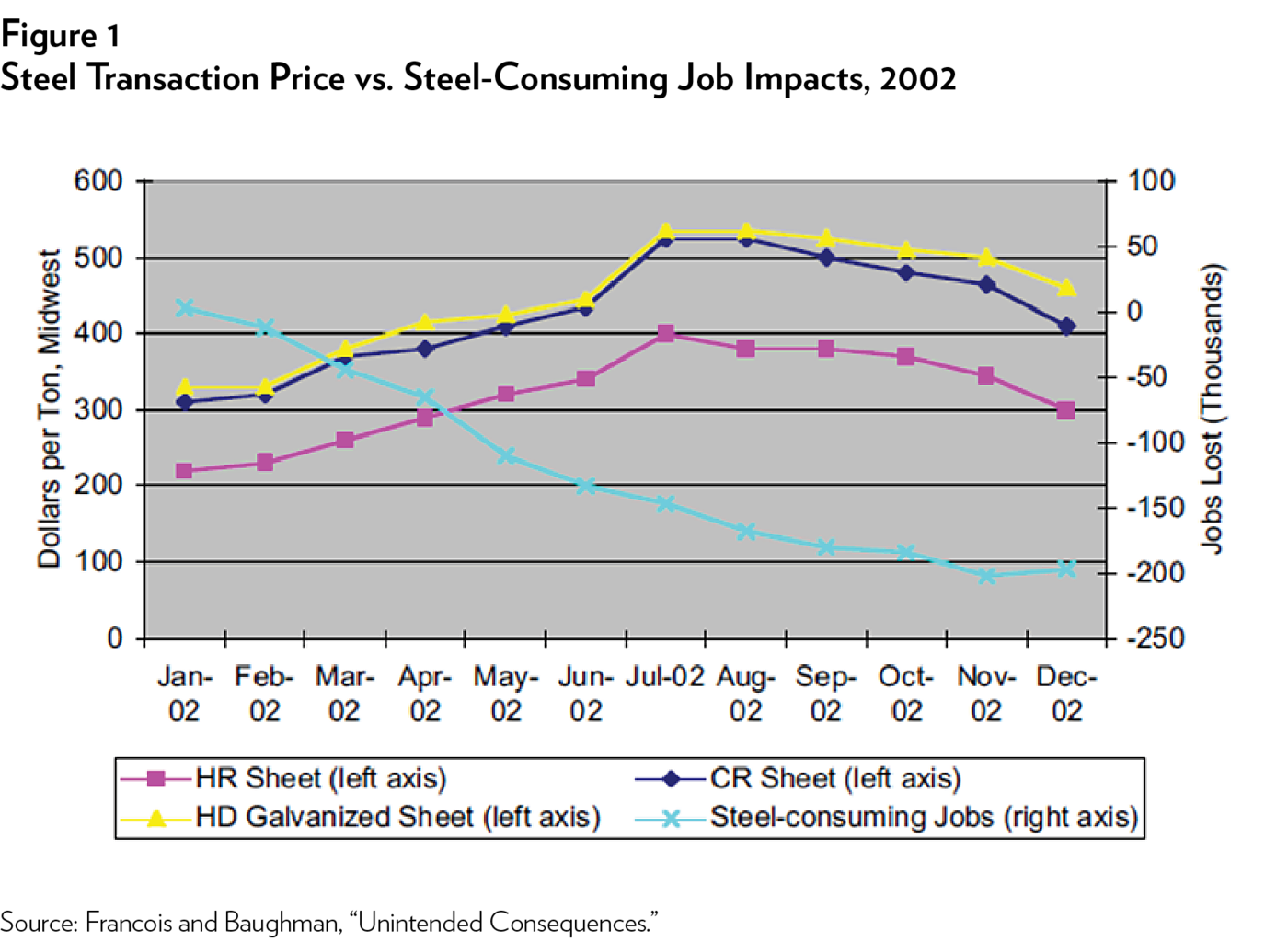

A 2003 study of steel safeguards found that the tariffs were a major contributor to domestic shortages and skyrocketing steel prices in 2002, thus putting U.S. steel-consuming manufacturers at a severe disadvantage relative to their foreign competition and crippling their profits. The authors estimated that because of higher steel prices in 2002, approximately 200,000 Americans—50,000 in downstream manufacturing—lost their jobs, with heavy losses in “rust belt” states, such as Ohio, Michigan, Illinois, and Pennsylvania.88 By contrast, only 187,500 Americans worked in the entire steel industry at that time. (See Figure 1.)

The steel safeguards were challenged at the WTO and eventually removed in 2003 following adverse dispute settlement rulings; the antidumping duties remained. Yet despite decades of protection and billions of dollars in government subsidies, Barfield noted in 2003 that “the U.S. steel industry has dramatically shrunk, with employment down by two-thirds … capitalization only one-tenth its former valuation,” and 12 different bankruptcies between 1998 and 2000 alone.89 These exact same dynamics continue today: As of October 2016,90 191 of 373 antidumping and countervailing duty orders in place were on iron and steel products. Yet the industry continued to clamor for more import protection and government assistance.91 Both points testify to the duties’ failures (and the steel industry’s political connections).

The failure of trade remedy laws to revive ailing domestic manufacturers is not unique to steel. For example, although U.S. paper-makers benefit92 from 19 different antidumping and countervailing duty orders on a wide range of paper products,93 petitioning firms have still declared bankruptcy,94 and the workforce has steadily declined since 1995 (640,000 to 370,000).95 A 2017 review of all U.S. antidumping investigations against Chinese imports between 1998 and 2006 revealed that the duties reduce Chinese imports and increase prices of subject merchandise in the U.S. market, but these effects “dissipate approximately 2 years after the antidumping decision” and imports from other countries simply increase to replace the declining Chinese imports. Such results “cast doubt on the effectiveness of antidumping actions against China as mechanisms for protecting U.S. producers.”96 Previous studies of U.S. antidumping protection found similar effects (or lack thereof).97

The failures of steel and paper industry protection are also indicative of a larger problem plaguing U.S. trade policy in recent years: the imposition of painful antidumping duties on imports of upstream manufacturing inputs used by large and globally integrated U.S. manufacturers. According to my colleague Daniel Ikenson, writing in a 2011 paper, four-fifths (130 of 164) of U.S. antidumping duties imposed between 2000 and 2009 targeted intermediate goods (i.e., inputs consumed by U.S. producers in the process of adding value to make their own downstream products).98 Ikenson did not quantify the precise economic harms caused by these duties but showed that in dozens of these cases the import restrictions hurt downstream industries that annually export over $100 billion and/or employ over 1 million U.S. workers. Furthermore, he found that in 35 of the 99 antidumping orders imposed on manufacturing inputs, the entire petitioning domestic industry consisted of just one firm, while “the ensuing trade restrictions affected dozens or hundreds of downstream firms in numerous industries.” Ironically, Ikenson found that one of the most victimized industries under this regime was U.S. semiconductor manufacturers (whose “costs are inflated by antidumping duties on barium carbonate, tetrahydrofurfuryl alcohol, and ‘high and ultra-high voltage ceramic station post insulators’”)—the same industry that sought antidumping protections decades earlier. Ikenson’s analysis led him to conclude that a “law … originally rationalized as a tool to protect consumers and competition” has had precisely the opposite effect.

Most recently, President Barack Obama’s imposition of “special” safeguard duties on Chinese tire imports—at 35 percent in 2009, 30 percent in 2010, and 25 percent in 2011—again demonstrates the costs of protectionism. According to a 2012 PIIE study, the tariffs imposed $1.1 billion in additional costs on U.S. tire consumers in 2011. Even under the most generous assumptions regarding the tariffs’ effect on U.S. tiremaking jobs, the cost per manufacturing job saved (a maximum of 1,200 jobs) was at least $900,000 that year. Furthermore, the primary recipients of these rents were not U.S. workers, but foreign producers in countries such as Thailand, Indonesia, and Mexico that were not subject to the safeguard and thus increased shipments to the United States in place of Chinese imports. Overall, the tariffs cost approximately 2,531 American jobs, as the United States lost far more jobs in retail and other industries than it potentially preserved or created in tire manufacturing. Finally, in response to the tire tariffs, the Chinese government retaliated against U.S. exporters of chicken parts, costing that industry approximately $1 billion.99

Other forms of U.S. nontariff barriers to imports have created similar problems. For example, in 2009, the United States implemented mandatory Country of Origin Labeling (COOL) that imposed burdensome new requirements on most meat imports, including those from Canada and Mexico.100 Many U.S., Canadian, and Mexican ranchers and meat-packers share grazing land across borders and have integrated supply chains, meaning that for them, compliance with the onerous COOL system was virtually impossible. As such, the USDA estimated in 2015 that the COOL regime imposed $2.6 billion in implementation costs on U.S. producers, meatpackers, and retailers ($1.3 billion for beef alone); resulted in economic welfare losses totaling $8.07 billion for the U.S. beef industry and $1.31 billion for the pork industry; and despite some “small” economic benefits for consumers in the form of increased information, would “result in an estimated $212 million reduction in consumers’ purchasing power” by 2019.101

The COOL case also exposed U.S. exports to potential retaliation from foreign governments. In December 2008, Canada and Mexico challenged the COOL regime at the WTO, arguing that the COOL standard deviates from international labeling standards, does not fulfill a legitimate regulatory objective, and would exclude all beef or pork produced from livestock exported to, but slaughtered in, the United States.102 In May 2015, the WTO Appellate Body ruled against the United States in its final appeal and agreed with Canada and Mexico about the discriminatory effect of the original and since-modified COOL regimes. The WTO subsequently authorized the two complainants to impose over $1 billion in retaliatory duties on U.S. exports to their markets, but the United States finally repealed the COOL system in early 2016 before those duties were imposed.103

The New Era of Integration and (Potential) Retaliation. The COOL and steel safeguards cases also illustrate new and important ramifications for U.S. protectionism that were mostly absent from previous periods. The WTO, combined with a substantial increase in U.S. integration into the global economy, has made foreign government responses to American protectionism more painful than before. The WTO not only expanded and clarified the WTO members’ multilateral obligations—covering, for example, subsidies, services, investment, and nontariff barriers—but also provided a new, binding dispute settlement system to challenge U.S. protectionism and to retaliate in cases of noncompliance. As already noted, this system has provided impressive benefits for the United States as a complainant, but it has also provided similar benefits for trading partners frustrated by American trade barriers. And with U.S. exports increasing from only 7 percent of GDP in 1985 to around 13 percent today,104 such retaliation also could be far more painful than if it had occurred during the Reagan era or earlier.

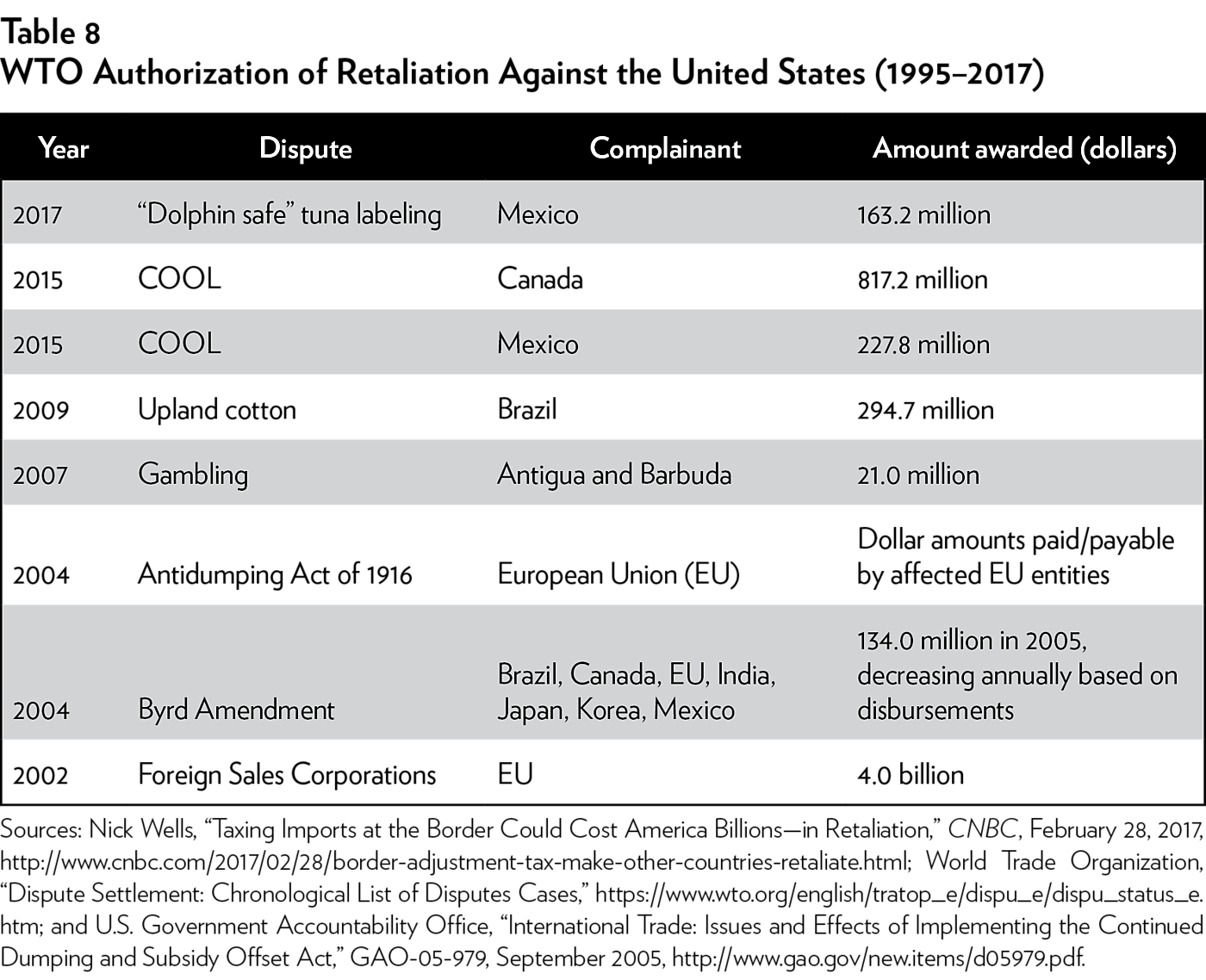

As shown in Table 8, the WTO has authorized retaliation against the United States—which typically involves additional duties on U.S. exports to the complaining member’s territory—in eight different disputes. Such retaliation, or the potential threat thereof in other disputes, has encouraged U.S. compliance in most cases—a trend followed by other WTO members, such as China and the EU, including when the United States is the complainant.105 As such, the WTO has proven to be an effective check on the protectionism of not only the United States, but also most other WTO members.