There are a number of policy areas where additional complaints are possible. The U.S. Trade Representative’s Office (USTR) has been gathering detailed information on China’s practices for years and should file complaints on this basis, coordinating these efforts with key allies. And for those areas that are not well covered by WTO rules, such as state-owned enterprises, the United States should work with these allies to develop new rules. So far, the Trump administration has mainly relied on unilateral tariffs to open the Chinese market, but these are likely to hurt Americans, while not having much effect on Chinese trade practices. The multilateral route is a better approach to disciplining these trade practices and making China more market-oriented.

Disciplining China’s Trade Practices at the WTO: How WTO Complaints Can Help Make China More Market-Oriented

The Trump administration has argued that the World Trade Organization (WTO) has failed to address China’s “unfair” trade practices. While it is true that China’s economic rise poses a unique challenge to the world trading system, WTO dispute settlement has more potential to address China’s practices than the administration believes. If the Trump administration really does want the Chinese economy to be more market-oriented, it should make better use of WTO rules by filing more complaints against China. While it is often accused of flouting the rules, China does a reasonably good job of complying with WTO complaints brought against it.

Related Event

Chinas New Authoritarian Ideology

Online Policy Forum

China is not only a rising superpower, but it also presents an authoritarian political model, which may well become the 21st century’s main alternative—and challenge—to liberal democracy. Timothy Cheek and Lynette Ong describe this phenomenon in an online policy forum. Understanding it will be key to evaluating China’s ambitions and anxieties—and to devising the right policies to protect freedom.

Introduction

There is a growing bipartisan sentiment in Washington that Chinese trade practices are a problem, since these practices are unfair to American companies in a number of ways. But there is disagreement about the appropriate response. Can multilateral institutions be of use here? Or is unilateralism the only way?

The Trump administration believes that the international dispute settlement system of the World Trade Organization (WTO) offers no effective remedy for these practices, and prefers an approach that relies mostly on unilateral tariffs. The administration sees the issue as follows. China’s mercantilist state systematically discriminates against foreign products and foreign producers in China while forcing foreign companies to hand over their intellectual property (IP) as the price of access to China’s large and growing market. China engages in widespread cheating in its trade practices, including not only high tariffs, domestic content requirements, and other traditional forms of protectionism, but also rigged regulations that erect trade barriers by favoring Chinese companies and outright theft of foreign IP. And, Trump and his trade cohorts say repeatedly, there is virtually nothing the United States can do under current WTO rules to stop this predatory Chinese behavior.

Leading administration officials have referred to the WTO’s “abject failure to address emerging problems caused by unfair practices from countries like China”1 and its “inability to resolve disputes, limit subsidies or draw China into the market status that was envisioned when China joined the WTO”2; and they have declared that the WTO “is not equipped to deal with [the China] problem.”3 Since Trump became president, the United States has pursued only one new WTO complaint against China (although it has continued to litigate some cases brought by the Obama administration). According to the U.S. Trade Representative’s Office (USTR), in a report issued in January of 2018, “The notion that our problems with China can be solved by bringing more cases at the WTO alone is naïve at best, and at its worst distracts policymakers from facing the gravity of the challenge presented by China’s non-market policies.”4 A recent report by the USTR has gone so far as to call China’s entry into the WTO in 2001 under the terms adopted at that time a mistake.5

Even some scholars with no allegiance to Trump have their doubts about the sufficiency of WTO rules and the capacity of the WTO as an international institution to confront the unique challenge of an economy like that of 21st-century China. Harvard Law professor and former USTR official Mark Wu has written that “the WTO is struggling to adjust to a rising China” because of “China’s distinctive economic structure.” He notes, “The WTO dispute settlement system has effectively resolved certain disputes and will continue to do so,” but “the system has its limits.”6 He adds, “Overall, I contend that without major change China’s rise, should it continue, will contribute to a gradual weakening of the WTO legal order.”7

While it is true that China’s rise poses a unique challenge to the WTO-based world trading system, and there are limits to what can be done to counter China’s mercantilist and protectionist practices under existing WTO rules through dispute settlement, this paper makes the case that WTO dispute settlement has considerably more potential than the Trump administration thinks, and it offers, over the long term, a far more effective means of responding to protectionist Chinese trade policies than the current Trump policy of applying illegal unilateral tariffs on billions of dollars’ worth of Chinese products entering the U.S. market—and threatening hundreds of billions more. While WTO complaints alone cannot solve all of America’s commercial problems related to China, they can be a crucial part of the ongoing effort to encourage China to see that the best way for it to rise is not by the mercantilism and protectionism of state-managed trade but, instead, by becoming a market-oriented, rule-following, fully developed nation.

Supporting China’s membership in the WTO in 2001 was not a mistake by the United States. All 163 other members of the WTO, including the United States, are much better off because China is inside the rules-based global trading system and has not been left outside it. China has made great strides since 2001 toward full compliance with the rules of the WTO trading system.

And yet, even greater strides remain to be made. Today, China faces a choice: Will it continue to move toward free markets, or will it entrust the future of the Chinese people to an economic philosophy extolling state-devised and state-driven economic decisionmaking that limits foreign competition and tips the scales against foreign producers and their products? As China confronts this choice, WTO rules and disciplines offer one opportunity, and a much better one than some believe, for showing China the merits of making the right choice of a much freer market economy.

This paper proceeds as follows. First, it explains that while some of China’s specific practices may be a problem, its desire for economic development is natural and appropriate. Whatever polices are adopted with respect to Chinese trade should not try to limit China’s economic ambitions.

Second, it argues that for those practices that are protectionist or otherwise problematic, international trade rules should be utilized to steer China in a market-oriented direction. Despite any skepticism about China’s willingness to play by the rules, reviewing the cases brought against China makes clear that China’s track record in WTO compliance is actually quite good.

This paper then argues that the problems the United States and others have with China are just as much about the failure to utilize existing WTO rules as they are about China’s bad behavior. Uncovering China’s WTO violations is challenging but it can be done, and many potential complaints have been overlooked, in particular in relation to intellectual property protection, forced technology transfer, and subsidies. The paper explains these issues briefly in the main body, and then in more detail in Appendix 2.

The paper also cautions against condemning China for actions that are similar to what others do or are not as nefarious as they are portrayed. The case against China is weakened by hyperbole and exaggeration.

Finally, this paper considers gaps in existing rules and calls for an expansion into several new areas.

It will doubtless be insisted by those busy imposing unilateral tariffs that bringing WTO legal claims will require too much time and too much trouble and that, even if the United States prevails, a remedy is at best several years away. While there is some truth here, the current trade war will also require time and trouble and impose considerable economic costs on the United States as China retaliates, and then the United States ups its sanctions, and China responds again, and so on. What other untold and untoward consequences will there be from an abandonment by the United States of reliance on multilateral WTO remedies and thus of the international rule of law? Would not U.S. trade interests be better advanced by taking the time instead to seek and implement a binding and enforceable WTO judgment backed by the lawful threat of significant economic sanctions?

Despite the repetitions of the Trump administration insisting otherwise, the WTO remains the best hope for disciplining China’s errant trade practices. Rather than abandon the WTO in its trade relations with China, the United States should rely on the WTO more than it has so far. Ideally, in cooperation with other major trading countries, the United States should take action within the WTO to ensure that China complies with its WTO obligations, and in this way push China to fulfill its promise of a transition to a market economy.

In Defense of China’s Economic Ambitions

In recent years, there has been growing concern in the United States and elsewhere about China’s lofty economic ambitions. Through its “Made in China 2025” industrial policy, China, it is said, has set out clear goals for its eventual expansion into, and domination of, many advanced high-tech industries, such as robotics, advanced information technology, aviation, and new-energy vehicles.8 There is widespread, increasing, and legitimate concern in the United States that Americans will suffer as a result, as our own industries are harmed by unfair Chinese competition, and as Americans have to rely more and more on China for products, with a potential risk to our national security. Beyond this, the current American conventional wisdom seems to suggest that China’s economic rise may contribute to the decline of the United States.

In reality, the fear that China’s rise will lead inevitably to America’s fall is overblown. Competition in the world economy is not a zero-sum game. The economic success of other countries does not lead to our economic failure. The United States has been through this before, with the industrialization of Japan and other countries in the decades following World War II. Not only have we lived to tell the tale, but we are actually better off as a result. As other countries have risen, Americans have prospered alongside them. Without a doubt, China poses challenges different from those confronted earlier. Yet, despite these unique challenges, with the right combination of U.S. policies and Chinese responses, China’s continued economic development can have the same benefits as earlier examples of development.

There is also this: It is far better for America that China should rise than that it not rise. The economic failure of China would reveal to both countries and to all the world the fact—apparently little understood by the current president of the United States—that the Chinese economy and the American economy are linked together and are in many ways interdependent.

And China has every right to rise. It is not forever fated to be a low-wage assembly line for the rest of the world. Like every other country, it has the right to climb the ladder of comparative advantage in pursuit of more value-added growth in an expanding global economy. While there are certainly reasons to be concerned about a great many aspects of China’s current statist approach to advancing its industries, there is nothing inherently wrong with China’s moving up the economic ladder. Furthermore, the United States benefits if the Chinese people prosper. The Chinese people and the American people alike will prosper most if both China and America are part of an open and rules-based global economy.

Just as we Americans are better off with the rise of Japanese car makers, we are better off with additional competition from Chinese companies in numerous sectors. If China begins to compete in high-tech goods, that will be disruptive to certain Americans, just as it was when foreign companies began competing with us in textiles and clothing, furniture, and other low-skill manufacturing sectors. But no matter how much some people may lament the decline of particular industries, few would suggest the American economy was better off in the past or would be better off without the innovation-inspiring benefit of that foreign competition. We could have an economy where Americans were sheltered from competition, but why would we want to? The lower-quality, more expensive products for consumers and the less innovative and thus less competitive sheltered industries that would be the result would not be worth the tradeoff. Furthermore, wealthier foreign customers are also in the United States’ interest. Japan, China, and others can now buy a lot more American goods and services than they could in the past. That is of great benefit to American workers and businesses.

A crucial point to recall is that China is industrializing at a time when others have already paved the way. Countries develop at uneven rates, the reasons for which are complex. For those that develop later, it is natural to look at what others have done before. It does not make sense for China to reinvent the wheel, or the automobile. To some extent, China can and should copy what others have done. As an example, it recently began developing a wine industry, with input from experts from Europe.9 If knowledge and expertise already exist, China and other latecomers should use it, whether the product is wine or semiconductors.

From the standpoint of the consumer, the additional competition is of great benefit. What is needed is to find the right balance between the spread of knowledge and the protection of intellectual property rights. WTO Members have tried to strike this balance under the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS Agreement). Intellectual property protection is, in a strict sense, an exception to free trade in that it limits free trade in ideas. However, this exception is thought to be justified by the need to provide incentives for the innovations that are often the products of new ideas.

At the same time, some behavior related to economic catch-up can be highly problematic. For example, where governments or corporations steal trade secrets from foreign competitors—as has been alleged with China—or where governments engage in classic forms of protectionism by imposing tariffs and by granting subsidies in violation of agreed-on global rules, such behavior is not acceptable. We do not want companies hacking into competitors’ networks, and protectionism undermines rather than promotes competition.

On the other hand, companies should be free to buy a competitor’s product and take it apart to see how it works. They should be able to hire people away from their competitors, even in foreign nations. They should even be able to buy their foreign competitors, a routine practice for which Chinese companies have been criticized. These are normal ways companies compete, and just as it is acceptable when American companies do these things, it should be acceptable when Chinese companies do the same.

International trade rules should push development toward this sort of productive competition and should discourage harmful practices. In essence, the rules should allow Chinese companies to look to foreign innovations as inspiration but force them to stay within mutually agreed-on legal boundaries of governmental and business behavior.

That is precisely what existing trade rules do. With regard to products, WTO rules prohibit discriminatory taxes and regulations, as well as product regulations that are overly trade-restrictive, food safety regulations that are not based on science, and certain kinds of subsidies. There are also detailed provisions on intellectual property protection and enforcement. Critics of WTO dispute settlement as a solution to problems with China underestimate how much its rules can help with China’s practices.

Part of the problem right now may be the limited number of enforcement actions taken against China. There have been some WTO complaints, but a wide range of Chinese practices that are supposedly of concern have not been challenged at the WTO. The lesson China might be drawing is that if its practices are not challenged it is because the rest of the world tacitly accepts them. Hence there is a compelling need to challenge Chinese actions when they are unfair to foreign products and foreign competitors in the Chinese marketplace and beyond.

The focus of this debate right now is China, but it will not end there. Development in other countries is in progress or is coming soon—Vietnam, India, and many African countries, to name just a few. As with China, it is good for Americans if these countries grow wealthier, but we are right to insist that they grow in ways that are consistent with agreed-on international rules and with fundamental fairness.

The controversy over China’s rise tells us that we must handle this development process appropriately. China’s rise has been dominated by rhetoric that exaggerates the problem and misunderstands the rules of the trading system. The trade rules that do exist can be useful, but they are not self-enforcing. They must be invoked by governments.

China’s 2025 plan is ambitious. It wants to be “globally competitive” and a “leader” in all of these high-tech industries. For the most part, this should not cause concern. We are all better off with more competition, and if China can become competitive in advanced technology sectors and lead the way on innovation, we all benefit.

The rhetoric China uses is interesting, but the more important issue is its actual trade practices. If Chinese companies compete with hard work and ingenuity, we should celebrate their success. But if China discriminates against foreign companies, or offers subsidies to its own companies or favors them in other ways, other governments should challenge those practices at the WTO. And if there are questionable practices not covered by the rules, other governments should coordinate an effort to get China to agree to new rules.

Yes, China has every right to rise, but every other member of the WTO has the right to insist that China must rise within the bounds of the global trade rules to which it has agreed. And where rules do not yet exist, we must find ways to negotiate and agree on them. The message we send China should be clear: we want you to continue to rise, but you must follow the same rules as other WTO Members, and you must work with us and with all other WTO Members to establish the additional rules that we need.

China’s Respectable Compliance Record in WTO Disputes

One of the reasons for the skepticism that exists about using WTO rules to challenge China’s trade practices is the idea that China “cheats” and therefore the rules are worthless. In fact, as this section of the paper demonstrates, China has a relatively strong record of compliance in the complaints that have been brought against it so far.

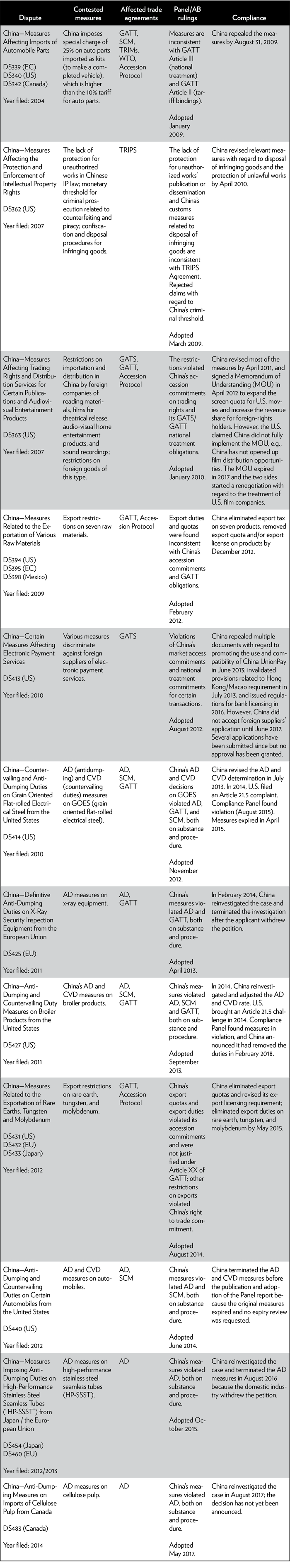

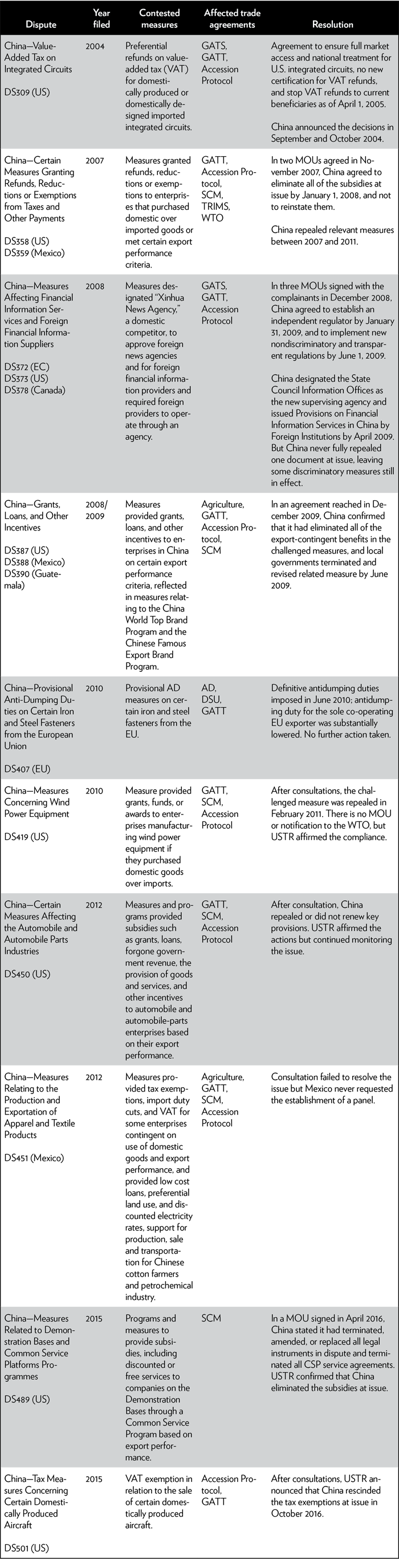

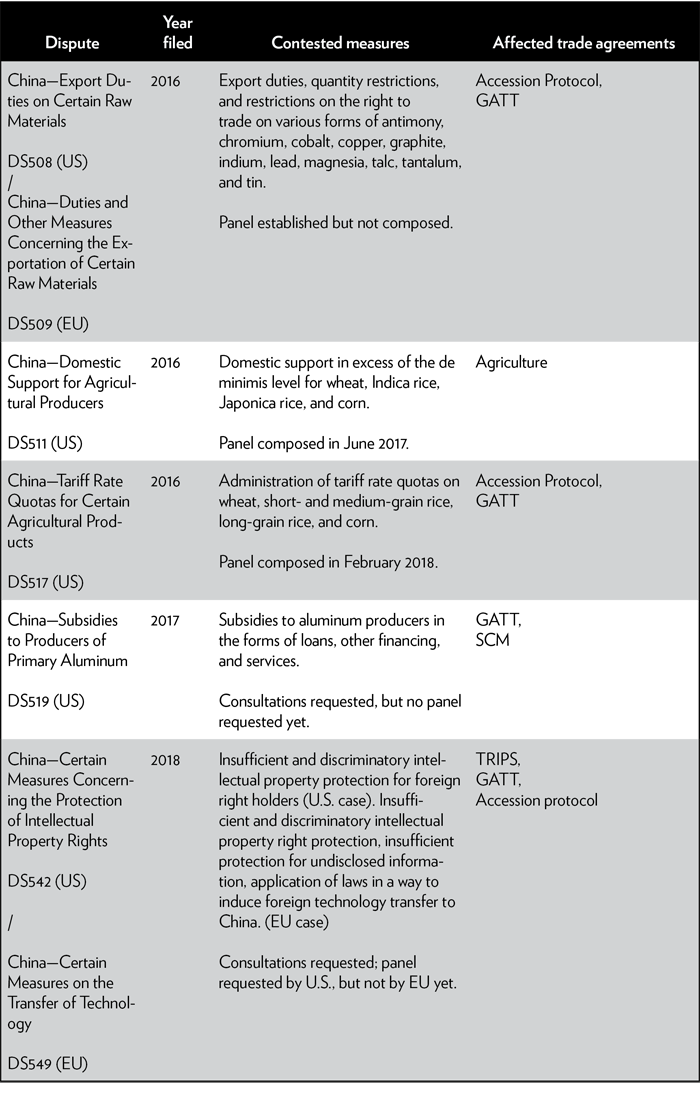

China joined the WTO in 2001. The first complaint against it was brought in 2004, with governments perhaps letting China gain some experience within the system before challenging it in dispute settlement. From 2004 to 2018, 41 complaints were brought against China, on 27 separate issues, or “matters” in WTO-speak—legal claims of actions inconsistent with WTO obligations, sometimes with multiple countries complaining about the same matter, resulting in more complaints than matters. (Appendix 1 provides details on these complaints and China’s responses.) During that time, China was second only to the United States in the number of complaints it faced.

Of the 27 matters litigated against China, 5 are still pending, 12 were litigated all the way through, and 10 were resolved through some kind of settlement, or not pursued after the measure was modified. These cases addressed a wide range of issues: export restrictions, subsidies, intellectual property protection, discriminatory taxes, trading rights, services, and trade remedies.

In all 22 completed cases, with one exception where a complaint was not pursued, China’s response was to take some action to move toward greater market access. This was done either through an autonomous action by China, a settlement agreement, or in response to a panel or appellate ruling.

In the cases where there was a WTO ruling, there was sometimes a dispute about compliance with the ruling (as happens with other countries as well), and China’s compliance came only after the follow-up complaint procedure provided for in WTO law (Article 21.5 of the WTO’s Dispute Settlement Understanding). In other cases, the complainants have disputed whether China has complied but have not brought an Article 21.5 complaint to push it to comply.

The overall picture of China’s response to WTO complaints looks very much like the situation of other governments that face such challenges: China has made efforts to comply, although some issues are still contested. The actual extent of Chinese compliance with WTO judgments has been questioned; in some instances it has been seen by some as only “paper compliance.”10 But there are no cases where China has simply ignored rulings against it, as has happened with some other governments. For example, the United States has not complied with the WTO ruling in the cotton subsidies complaint brought by Brazil, and the European Union (EU) still does not allow hormone-treated beef to be sold there even after losing a complaint brought by Canada and the United States.

The lesson here is that bringing WTO complaints against China works. It does not work perfectly in all cases, but that is no different from the situation in other countries. As Mark Wu, despite his reservations about the efficacy of WTO dispute settlement with respect to China, has acknowledged, thus far the WTO “has served its purpose effectively as a forum to enforce China’s trade obligations. On the numerous occasions when the WTO has ruled against China, the Chinese government has willingly complied with the judgment and usually altered its laws or regulations to comply with WTO rules.”11

Uncovering China’s Disguised Protectionism and WTO Violations

One reason why some question the suitability of WTO dispute settlement for resolving trade disputes with China is the lack of transparency in Chinese governance. A recurring refrain from the United States is the difficulty of discerning what the Chinese government is doing, either directly or indirectly. When has the Chinese government taken an action—what in trade law is called a “measure”—that falls within the scope of the jurisdiction of the WTO treaty and thus of WTO dispute settlement? All too often it is difficult to tell, and all too often the Chinese government makes it more difficult with the opacity of its administrative regime.

Hence, one reason for the current reluctance of the Trump administration to pursue WTO remedies instead of simply imposing punitive tariffs is the sheer labor that often goes into proving that there is indeed a Chinese measure that can be challenged in the WTO.

Yet, WTO rules make this task easier than some think, for two reasons. First, the rules set out a broad scope for the measures that can be challenged. The concept of measures is not limited solely to statutes and regulations; it also includes “the acts or omissions of the organs of the state, including those of the executive branch.”12 This standard covers a wide range of Chinese national and local government behavior, as well as governmental behavior that is intermingled with that of Chinese state-owned enterprises and the still-growing Chinese private sector.

Second, WTO rules contain numerous reporting requirements, under which the Chinese government must disclose its policies. If it does so, the United States will have the information it needs to bring the complaints. If it does not, China will be in violation of these reporting requirements.

In addition, the USTR has been gathering evidence of questionable Chinese trade practices for years, and the Section 301 report presents a substantial amount of it. There may be a few issues where more evidence would be useful, but there is no shortage of detail on how the Chinese government has behaved. The task now is to take that evidence and turn it into WTO complaints.

Start Bringing the WTO Complaints

Four promising areas of WTO complaints against China are general intellectual property protection and enforcement; trade secrets protection; forced technology transfer; and subsidies. This section provides a brief overview of each, with additional details on possible legal claims included in Appendix 2.

Quite rightly, President Trump and his administration are, in their unfolding trade strategy, targeting Chinese transgressions against U.S. intellectual property rights. Intellectual property is a major engine of the American economy. According to the most recent numbers from the U.S. Department of Commerce, intellectual property accounts for 38.2 percent of the U.S. GDP; U.S. IP-intensive industries provide 27.9 million jobs directly and an additional 17.6 million jobs indirectly through their supply chains, and these jobs pay 46 percent more than jobs in non-IP-intensive industries.13 (By contrast, the U.S. steel industry employs 143,000 workers, and there are 76,000 workers in the U.S. coal industry.14)

Unquestionably, pervasive intellectual property violations are a threat to millions of U.S. jobs in critical innovative U.S. industries. The U.S. International Trade Administration has estimated that U.S. IP-intensive industries doing business in China have lost about $48 billion in sales, royalties, and license fees to various forms of encroachment on their intellectual property rights. These U.S. firms have spent $4.8 billion to address possible Chinese IP infringements. An improvement in intellectual property protection and enforcement in China to levels comparable to those in the United States would likely translate into 923,000 new jobs in the United States.15 And these most recent numbers are from 2011—before the recent intensification of China’s mercantilist industrial strategy.

After 17 years in the WTO, China still falls far short of fulfilling its WTO obligations to protect copyrights, trademarks, patents, and other intellectual property rights. Millions of Chinese live on the illegal gains of widespread counterfeiting of U.S. and other foreign products. The Chinese, for example, are “addicted to bootleg software.”16 According to the Business Software Alliance, about 70 percent of the software used in China, valued at nearly $8.7 billion, is pirated.17 The annual cost to the U.S. economy worldwide from pirated software, counterfeit goods, and the theft of trade secrets “could be as high as $600 billion.”18 China “remains the world’s principal IP infringer,” accounting, for example, for 87 percent of the counterfeit goods seized upon entry into the United States.19

Before taking unilateral action outside the WTO in response to widespread Chinese IP infringements, the United States should take a closer look at the substantial rights it enjoys under the WTO’s TRIPS Agreement for protecting U.S. intellectual property against theft and other abuses, in particular those obligations related to the domestic enforcement of these protections. Potential remedies in the WTO exist and should not be ignored, and these remedies can be enforced through the pressure of WTO economic sanctions.

A more specific obligation related to intellectual property is that American companies have, in effect, been forced to turn over their technology to Chinese partners—in some cases by revealing their trade secrets—in exchange for being allowed to do business in China and have access to the booming Chinese market. Here, Article 39 of the TRIPS Agreement, which establishes a WTO obligation for the “Protection of Undisclosed Information,”20 can help. The United States was among the leaders in advocating the inclusion of Article 39 in the TRIPS Agreement, but the United States has, to date, not initiated an action in WTO dispute settlement claiming a Chinese violation of this WTO obligation.

Beyond intellectual property, there have been long-standing though somewhat vague allegations from U.S. industry groups that China forces foreign companies who wish to operate in China to make investments through joint ventures, and to then transfer their technology to their Chinese partners. As they describe it, transferring technology to Chinese companies is often a condition for the ability to make an investment there. Specific details of these arrangements are difficult to uncover. The companies involved may be reluctant to complain because they fear having their investment permission revoked by the Chinese government. All the same, in response to the USTR’s request for comments under Section 301 regarding China’s trade practices, a wide range of organizations have identified forced technology transfer as a concern. There is a specific provision of China’s WTO Accession Protocol that addresses the issue of forced technology transfer. The United States should invoke it as the basis of a WTO complaint.

Finally, one of the most frequently raised concerns about Chinese trade practices is the Chinese government’s provision of subsidies to both state-owned enterprises and private companies. These subsidies are offered through a variety of programs, including the Made in China 2025 initiative and its specific implementing measures. Fortunately, the WTO has extensive and detailed rules on subsidies that can be used to challenge China’s behavior. WTO Members have brought several complaints against Chinese subsidies already, including an ongoing case related to agriculture subsidies (see Appendix 1), and there are additional complaints still to be brought.

Don’t (Always) Believe the Hype

While there are many justified complaints about China, it is important to examine each allegation objectively. There is a tendency these days to demonize China for everything it does, even when its practices are similar to those of other countries. Certainly there are some Chinese trade practices that merit criticism, but the case against China is weakened when unsupported claims are included.

For instance, some people see China’s antitrust investigations into the practices of foreign companies as “predatory regulatory interventions” in the market. The famous “China Shock” economists David Autor, David Dorn, and Gordon Hanson have put forward an antitrust case against Qualcomm from 2015 as an example.21 But was this case really an example of Chinese protectionism?

Qualcomm’s practices in China were covered by the provision of China’s anti-monopoly law related to “abuse of a dominant market position.” In early 2015, after a 14-month-long investigation, China’s National Development and Reform Commission found that Qualcomm abused its market dominance in wireless telecommunication technology and three related baseband chipset markets. Specific violations included setting unfairly high patent royalties, charging for expired patents, tying Standard Essential Patents (SEPs) to non-SEPs, forcing cross-licensing without considering the value, and adding other unfair terms in licensing agreements.22 In a settlement, Qualcomm agreed to a fine of $975 million.

Was there anything “predatory” about China’s behavior? When considering this question, keep in mind that Qualcomm has also been the subject of antitrust investigations in other countries for similar practices. In 2009, the South Korea Fair Trade Commission fined Qualcomm $200 million for the abuse of its dominant position in the chip market.23 That same year, the Japan Fair Trade Commission found that Qualcomm used its dominance in SEPs to coerce certain Japanese manufacturers of semiconductor integrated circuits to cross-license for free.24 And in 2015, the EU started investigating Qualcomm’s abuse of its dominant position in the LTE baseband chipset market by providing financial incentives to its buyers in order to secure an exclusive contract to squeeze out competitors. As a result, the EU imposed a $1.2 billion fine.25

In the United States, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) filed a complaint in federal court in 2017 charging Qualcomm with violating U.S. antitrust law. Specifically, the FTC challenged several Qualcomm practices, including collecting royalties that were beyond what was fair, reasonable, and nondiscriminatory for its patented chips, forcing cross-licensing without considering the value of cross-licensed patents, and using its monopoly in chip supply to force phone manufacturers to agree to Qualcomm’s preferred license terms.26 The case is currently pending in district court.

A second example is the frequent accusation that China is “stealing” U.S. intellectual property, a constant refrain in the U.S. media.27 Stealing and theft are strong accusations, and they do not always accurately describe the situation. In some instances, Chinese government or private-sector agents hack into U.S. corporate networks to take confidential business secrets. But other situations that have been lumped into the “theft” accusations look much less nefarious.

A recent White House report titled “How China’s Economic Aggression Threatens the Technologies and Intellectual Property of the United States and the World” talks about “state-sponsored IP theft through physical theft, cyber-enabled espionage and theft, evasion of U.S. export control laws, and counterfeiting and piracy,” but also identifies “technology-seeking, state-financed foreign direct investment” as one form of “economic aggression.” Along the same lines, the USTR Section 301 report on China’s unfair practices states, “The Chinese government directs and unfairly facilitates the systematic investment in, and acquisition of, U.S. companies and assets by Chinese companies, to obtain cutting-edge technologies and intellectual property and generate large-scale technology transfer in industries deemed important by state industrial plans.”28

Theft and purchasing are, in fact, very different. Theft is an unacceptable practice that governments should make every effort to curtail. Company purchases by willing buyers and sellers, by contrast, are generally positive events, with both sides benefiting. There may be situations where a sale to a foreign company raises national security concerns, but there is nothing inherently wrong with the practice. Also, less advanced economies trying to learn from their more advanced counterparts is not exactly new and was advocated by Alexander Hamilton for the United States.29

The lesson here is that we should not jump to conclusions about the propriety of government behavior simply because China is the one doing it. Objectivity is crucial here, and baseless claims can undermine legitimate efforts to bring reform to China.

Gaps in the Rules

Instead of a China trade policy consisting mostly of confrontation, the United States should rely more on negotiation. Unquestionably, the existing WTO rules are not adequate in all respects to deal with the unique challenges presented by China to the rules-based trading system. The remedy for the inadequacy of rules, however, is not abandoning those rules, but the adoption of more and better rules. The understandable frustrations of the United States and other WTO Members with the statist, mercantilist, and clearly protectionist aspects of a great many of China’s trade policies should not cause us to discard the rules-based trading system we have endeavored so long to establish as a crucial part of the liberal international order. Rather, it should cause us to redouble our efforts to reinvigorate the rules-based trading system by negotiating new rules to discipline protectionist actions and encourage China to adopt the market-based approaches that alone can secure long-term economic success for the Chinese people.

Ideally, these negotiations should be multilateral and should include China. As things stand now, China seems to see little benefit to any such negotiations: imposing unilateral and illegal tariffs on its products will not encourage it to sit down at the global negotiating table. Instead, China will retaliate with tit-for-tat tariffs and other trade restrictions of its own. But engaging China in WTO dispute settlement could—as has happened in other instances with other countries in the past—help inspire it to negotiate rather than litigate. What’s more, the likelihood of achieving this result would be greatly enhanced if the United States were joined as co-complainant by the EU, Japan, Canada, and others with similar concerns about Chinese trade practices. This, of course, would require a U.S. trade strategy of working in concert with our long-standing allies on trade instead of alienating them.

If China chooses not to participate in multilateral negotiations, then it should be given an incentive to do so by negotiations that proceed without China. The aim here should not be to “isolate” or to “contain” China, but to start a negotiating process in which China will eventually enlist for its own sake economically. These negotiations should be conducted within the legal framework of the WTO, in part so that China will have an automatic right to join in new rulemaking if it wishes to do so and if it agrees to abide by the new rules that are made.

Something akin to this trade-negotiating approach—albeit outside the legal framework of the WTO—was employed by the United States and 11 other Pacific Rim countries in the negotiation of the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP). The idea of the TPP was in part to set up a common standard of enabling rules for free markets over and above those already in the WTO treaty and—through the proven success of such a standard—give the Chinese government reason to join. Unfortunately, one of the first acts of the Trump administration was to pull out of the TPP, which has since been concluded successfully without the United States—but also without the combined economic presence the TPP would have had in the Pacific had President Trump not withdrawn.

A potential list of matters for negotiation is not difficult to compile:

- Chinese accession to the WTO Government Procurement Agreement, promised by China long ago when it became a member of the WTO

- negotiation of a bilateral investment agreement between the United States and China, which could become a template for new multilateral rules

- the United States’ return to the TPP, coupled with an invitation to China to join as well

- negotiation of new disciplines on subsidies for state-owned enterprises, building on the innovations in the TPP that were negotiated by former president Obama and then abruptly abandoned by President Trump

- negotiation of disciplines on forced localization of servers and other aspects of digital trade and digital trade in services

- negotiations on the vast array of trade in services in which the United States has a huge economic stake and a comparative advantage but limited market access in China, perhaps by rebooting the negotiations on services trade in Geneva in which the Trump administration has shown scant interest

- negotiations on stricter enforcement of intellectual property rights and on more explicit disciplinary measures on the transfer of technology and the sharing of trade secrets.

But there can be no negotiations if there is not first a willingness to negotiate. And, for all his talk of trade deals, President Trump has shown little interest in the give-and-take of actual international trade negotiations. Instead, he seems to be interested only in the take-it-or-leave-it of his personal version of “the art of the deal.” With some smaller countries, this may seem to him and his supporters to work. But this approach will not work for long. It will not work with all countries. And take-it-or-leave-it most certainly will not work with China, which has at least as much leverage over the fate of the American economy as the United States has over that of the Chinese economy. In truth, the fate of the two economies is in many ways one and the same, for the two are interdependent—a powerful reason for both the United States and China to choose to negotiate more and better rules on which they and all other WTO Members can agree.

Conclusion

The Trump administration may be skeptical about the value of filing WTO complaints against China, preferring the immediacy and contentiousness of unilateral tariffs. But if they are looking for effective approaches to addressing Chinese protectionism and other trade practices, WTO disputes are the better avenue. China has responded to U.S. tariffs with its own tariffs, rather than with market opening. By contrast, China has responded to previous WTO complaints with market opening. The WTO dispute process is not perfect, but it is a tried-and-true approach to this problem. Its biggest flaw is that it is underutilized. The Trump administration should work with U.S. allies to use the WTO dispute process to press China to fulfill its promises and become more market-oriented.

Appendix 1: China’s Response to WTO Complaints Filed against It

| Litigated cases | (12 matters / 19 complaints) |

| Resolved/abandoned cases | (10 matters / 15 complaints) |

| Recent pending cases | (5 matters / 7 complaints) |

Source: Office of the U.S. Trade Representative, the European Commission, and China’s Ministry of Commerce press releases; WTO website; and authors’ correspondence with government officials.

Note: The agreements under which complaints have been brought are: General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT); General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS); Agreement on Subsidies and Countervailing Measures (SCM); Understanding on Rules and Procedures Governing the Settlement of Disputes (DSU); Agreement on Trade-Related Investment Measures (TRIMs); Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS); Agreement on Implementation of Article VI of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade 1994 (AD); Agreement on Agriculture (Agriculture); Agreement Establishing the World Trade Organization (WTO); China’s Accession Protocol (Accession Protocol).

Appendix 2: Elaboration of Possible WTO Complaints against China

General Intellectual Property Enforcement

The WTO obligations in the Agreement on the Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights—the so-called TRIPS Agreement—are unique among WTO rules.30 Most WTO rules are “don’ts” imposing negative obligations. Don’t discriminate. Don’t apply tariffs higher than you promised. In contrast, the WTO rules on intellectual property rights are “do’s” imposing affirmative obligations. Do respect intellectual property rights. Do enforce them. Yet this affirmative aspect of WTO intellectual property rules has been largely unexplored in WTO dispute settlement. In particular, and despite widespread intellectual property violations in many other parts of the world in addition to China, no WTO Member has yet to challenge another Member with a systemic failure to enforce intellectual property rights.

Part III of the TRIPS Agreement is titled “Enforcement of Intellectual Property Rights.”31 Part III, comprising Articles 41 through 61, clearly consists of affirmative obligations. Section 1 of Part IV relates to “General Obligations” and consists of Article 41. Article 41.1 provides:

Members shall ensure that enforcement procedures as specified in this Part are available under their law so as to permit effective action against any act of infringement of intellectual property rights covered by this Agreement, including expeditious remedies to prevent infringements and remedies which constitute a deterrent to further infringements. These procedures shall be applied in such a manner as to avoid the creation of barriers to legitimate trade and to provide for safeguards against their abuse.32

This “shall” be done by all WTO Members; it is mandatory for compliance with their WTO obligations. But what does this obligation mean by requiring that effective actions against infringements must be “available”? Is this obligation fulfilled by having sound laws on the books, as is generally the case with China? Or must those laws also be enforced effectively in practice, which is often not the case with China? Precisely how demanding is this obligation in requiring real enforcement of intellectual property rights?

The Appellate Body has already been more than suggestive of the answer to this question. The WTO jurists have said that “making something available means making it ‘obtainable,’ putting it ‘within one’s reach’ and ‘at one’s disposal’ in a way that has sufficient form or efficacy.”33 Thus, simply having a law on the books is not enough. That law must have real force in the real world of commerce. This ruling by the Appellate Body related to the use of the word “available” in Article 42 and to a legal claim seeking fair and equitable access to civil judicial procedures under Section 2 of Part IV, which relates to “Civil and Administrative Procedures and Remedies.” The same reasoning would apply equally to the enforcement of substantive rights under the “General Obligations” in Article 41 in Section 1 of Part IV of the TRIPS Agreement.

In the past, the United States has challenged successfully certain parts of the overall Chinese legal system for intellectual property protection in WTO dispute settlement.34 Despite its overall concerns about enforcement by China of U.S. intellectual property rights, the United States has not challenged the Chinese system as a whole in the WTO on the basis of a failure to fulfill the specific enforcement obligations in Part III of the TRIPS Agreement. Instead of resorting to the illegality of unilateral tariffs and other arbitrary sanctions outside the legal framework of the WTO, the Trump administration should initiate a comprehensive legal challenge in the WTO, not merely to bits and pieces of particular Chinese IP enforcement, but rather to the entirety of the Chinese IP enforcement system as a whole.

Such a systemic challenge would put the WTO dispute settlement system to a test, to be sure. It would, what’s more, put both China and the United States to the test of their commitment to the WTO and especially to a rules-based world trading system. A systemic IP case against China in the WTO would involve a perhaps unprecedented amount of fact gathering. It would necessitate an outpouring of voluminous legal pleadings. It would, furthermore, force the WTO Members and WTO jurists to face some fundamental questions about the rules-based trading system. Yet it could also provide the basis for fashioning a legal remedy that would in the end be acceptable to both countries and could therefore help reduce a significant obstacle to mutually beneficial U.S.-China relations.

China has denied the allegations by the United States of systemic Chinese violations of U.S. intellectual property rights, saying, “We want to emphasize that the Chinese government has always set a great store by [intellectual property] protection and made achievements that are for all to see.”35 There have in fact been some improvements in some respects in IP protection since China joined the WTO in 2001. Yet widespread infringements continue and, in some of the innovative industrial sectors targeted by China strategically, seem to be increasing. China cannot expect the United States and other WTO Members to continue to respect all their trade obligations to China if China does not respect all its trade obligations to the United States and other Members of the WTO.

As it grows economically, China is growing as a force in world trade and thus in the WTO. China values its membership in the WTO, in part because China is aware of the considerable benefits it derives from membership. Professing its ongoing commitment to the WTO and to international trade based on accepted international rules, China has also insisted, correctly, that, “any trade measures that are taken by WTO Members must conform to WTO rules.”36 But this admonition applies not only to measures taken in retaliation against perceived trade violations; it applies also to the measures that are taken that give rise to those retaliatory measures.

Trade Secrets

A more specific obligation related to intellectual property is that American companies have, in effect, been forced to turn over their technology to Chinese partners—in some cases by revealing their trade secrets—in exchange for being allowed to do business in China and have access to the booming Chinese market.

Evidently ignored so far by the United States is Article 39 of the TRIPS Agreement, which establishes a WTO obligation for the “Protection of Undisclosed Information.”37 The United States was among the leaders in advocating the inclusion of Article 39 in the TRIPS Agreement, but the United States has, to date, not initiated an action in WTO dispute settlement claiming a violation by China of this WTO obligation.

Article 39 is a major innovation in intellectual property protection under international law. It is “the first multilateral acknowledgement of the essential role that trade secrets play in industry”38 and “the first multilateral agreement to explicitly require member countries to provide protection for . . . ‘trade secrets.’”39 One commentator on the Uruguay Round of multilateral trade negotiations that concluded the WTO treaty observed, “The inclusion of trade secrets under the TRIPS has been hailed as a major innovation.”40

Before the enactment of the TRIPS Agreement, “the protection of trade secrets was not considered part of intellectual property protection, but rather of generic unfair competition rules.”41 With the adoption of the TRIPS Agreement, “undisclosed information” was for the first time listed among the different forms of intellectual property in a global agreement. It is among the intellectual property rights that must be enforced under Part III of the TRIPS Agreement.42 Yet, a quarter century later, Article 39 has never been used. There is no WTO jurisprudence whatsoever on Article 39.

This is not because Article 39 does not provide protection. On the contrary, Article 39 specifies that “Members shall protect undisclosed information. . . .”43 This is a mandatory obligation for every WTO Member. “Undisclosed information” is not defined in so many words in Article 39; however, the circumstances in which information lawfully under the control of a private party can be protected against disclosure, acquisition, or use without its consent are spelled out in detail in the obligation. Information is protected under Article 39 if it is secret, has commercial value, and has been protected against disclosure.44

Under Article 39.2, information is secret if “it is not, as a body or in precise configuration and assembly of its components, generally known among or readily accessible to persons within the circles that normally deal with the kind of information in question.”45 This is capacious language that provides coverage for virtually all kinds of trade secrets occurring in modern global commerce. The secret—that is, “undisclosed”—information must have commercial value “because it is secret.”46 Thus, there must be a commercial value in keeping it secret. This, too, is language for the purpose of protecting contemporary trade secrets.

This requirement that the undisclosed information must have been protected against disclosure means that it “has been subjected to reasonable steps under the circumstances, by the person lawfully in control of the information, to keep it secret.”47 Article 39 gives no examples of what such “reasonable steps” might be, and there is no WTO case law to offer any guidance. This said, “the law can only protect secrets if they are protected by their holder.”48 Generally, under national legal systems that provide for protection of trade secrets, “secrets must . . . be kept within a company: only those persons that need to know the information in order to make use of it for the benefit of the company may have access to it; others are excluded.”49 Furthermore, “the higher the value of the secret is, the more sophisticated and costly the expected protection by its holder should be.”50Steps taken accordingly would seem to be among the “reasonable steps” for the purposes of Article 39.

Under Article 39, disclosure, acquisition, or use of undisclosed information without consent is prohibited only if it is done “in a manner contrary to honest commercial practices.”51 Footnote 10 to Article 39 states, “For the purpose of this provision, ‘a manner contrary to honest commercial practices’ shall mean at least practices such as breach of contract, breach of confidence and inducement to breach, and includes the acquisition of undisclosed information by third parties who knew, or were grossly negligent in failing to know, that such practices were involved in the acquisition.”52 Importantly, the inclusion of the phrase “at least” in this TRIPS footnote indicates that the practices specified in the footnote are not the only practices that may be “contrary to honest commercial practices.” Here, too, there is a broad scope for protection in Article 39.

Article 39 provides that the protection of undisclosed information by WTO Members is to be “in the course of ensuring effective competition as provided in Article 10bis of the Paris Convention (1967),” which is referenced in the TRIPS Agreement.53 Under Article 10bis, “Any act of competition contrary to honest practices in industrial or commercial matters constitutes an act of unfair competition,”54 and “the countries of the (Paris Convention) Union are bound to assure to nationals of such countries effective protection against unfair competition.”55

It could be argued—and some developing countries did indeed argue during the Uruguay Round—that the protections afforded by Article 10bis are sufficient to protect trade secrets. However, many countries at the time had neither sufficient laws nor efficient administrative procedures in place to protect trade secrets. Nor were trade secrets recognized as intellectual property in other international law. It was, therefore, “necessary to single out the trade secrets as property rights, so as to assure the broadest protection.”56 The inclusion of Article 39 in Part II of the TRIPS Agreement, relating to “Standards Concerning the Availability, Scope and Use of Intellectual Property Rights,” makes crystal clear that undisclosed information within the ambit of Article 39 is an intellectual property right that must be enforced under Part III of the TRIPS Agreement, relating to “Enforcement of Intellectual Property Rights.”

A specific focus of any action by the United States in WTO dispute settlement related to the failure of China to protect trade secrets will be the continuing shortcomings of the Anti-Unfair Competition Law of China (AUCL), which, as the USTR pointed out in its Special 301 Report for 2018, include “the overly narrow scope of covered actions and actors, the failure to address obstacles to injunctive relief, and the need to allow for evidentiary burden shifting in appropriate circumstances, in addition to other concerns.”57 As the USTR observes in the 2017 update of the AUCL, “despite long-term engagement from the United States and others—including from within China—China chose not to establish a standalone trade secrets law, and instead continued to seat important trade secrets provisions in the AUCL, an arrangement which contributes to definitional, conceptual, and practical shortcomings relating to trade secrets protection.”58

Those who would rather apply the broad illegal brush of unilateral tariffs instead of the sharp legal stiletto of a precise claim in WTO dispute settlement will protest that Article 39 has never been tested in a WTO dispute. This is true. Yet similar protests were heard 10 and 20 years ago against bringing legal claims in WTO dispute settlement under the Agreement on Technical Barriers to Trade and the Agreement on the Application of Sanitary and Phytosanitary Measures, which have both since been proven to be reliable tools for upholding and enforcing WTO obligations. Not having been tested is not the same as having been tried and found wanting. Until proven otherwise, a legal claim of a failure to protect “undisclosed information” under the novel obligation in Article 39 of the TRIPS Agreement must be seen as a potentially positive means to the end of protecting trade secrets.

It will certainly be said as well that proving a legal claim of illegal infringement of undisclosed information under Article 39 in WTO dispute settlement will not be easily accomplished. This also is true. As the complainant, the United States will have the burden of proving this and all its legal claims against China in a WTO dispute. First of all, in challenging the enforcement of the Chinese law, the United States, with respect to each alleged infringement of a trade secret, will have to show to the satisfaction of a WTO panel that there is in fact “undisclosed information” that composes a trade secret. Moreover, the United States will have to prove each particular instance of the illegal infringement of specific trade secrets.

All of this will necessarily involve the accumulation and submission of a veritable mountain of evidence—not easy in any case and certainly not easy in a case against a WTO Member with such an opaque and elusive economic and administrative system. Knowing this, the EU nevertheless recently filed a request for consultations with China in the WTO on China’s regulations on the import and export of technologies that includes a TRIPS Article 39 claim.59 In contrast, thus far, the United States has not invoked Article 39. Without question, China presents a formidable climb in the fact gathering for winning a WTO case. But the United States has climbed this mountain successfully before in a series of complicated WTO complaints it has brought against China and won. Why does the Trump administration seem to have so little confidence that the world-class legal advocates at the USTR can climb it again?

Forced Technology Transfer

There have been long-standing, though somewhat vague, allegations from U.S. industry groups that China forces foreign companies that wish to operate in China to make investments through joint ventures, and to then transfer their technology to their Chinese partners. Specific details on these arrangements are difficult to uncover. The companies involved may be reluctant to complain because they fear having their investment permission revoked by the Chinese government. All the same, in response to the USTR’s request for comments under Section 301 regarding China’s trade practices, a wide range of organizations have identified forced technology transfer as a concern.

As an example, the law firm of Stewart & Stewart has explained, “Technology transfer requirements are routinely included in joint venture contracts between foreign investors and domestic firms, especially state-owned firms, in China’s automotive sector.”60 In this regard, it noted, “BMW Holdings of the Netherlands agreed to license certain technology and operational know-how to a joint venture it formed with state-owned Shenyang JinBei Automotive Industry Holdings Co., Ltd. (now known as Brilliance) to produce automobiles in China.”61

In considering a possible WTO legal complaint, the specific role of the government here is crucial. Which Chinese government agencies or entities were involved, and how exactly did they pressure the foreign company to agree to transfer technology? These kinds of details will be crucial for a successful complaint. The Chinese actions seem to violate the spirit of WTO rules, but do they violate the letter of the law as well? There are at least two good legal avenues for a WTO complaint.

First, China is bound not only by the WTO obligations that bind all other WTO Members, but also by special rules to which it agreed as part of its accession agreement when it joined the WTO. These rules are contained in China’s Accession Protocol and Working Party Report, and are commonly described as “WTO-plus” obligations.

As part of these extra obligations that apply solely to China, Section 7(3) of

China’s Accession Protocol includes an

explicit reference to conditioning investment approval on technology transfer:

Without prejudice to the relevant provisions of this Protocol, China shall ensure that . . . any other means of approval for . . . investment by national

and sub-national authorities, is not conditioned on: whether competing domestic suppliers of such products exist; or performance requirements of any kind, such as local content, offsets, the transfer of technology, export performance or the conduct of research and development in China.62

This undertaking is further elaborated in Paragraph 203 of the Working Party Report, which was incorporated into the Protocol:

The allocation, permission or rights for . . . investment would not be conditional upon performance requirements set by national or sub-national authorities, or subject to secondary conditions covering, for example, the conduct of research, the provision of offsets or other forms of industrial compensation including specified types or volumes of business opportunities, the use of local inputs or the transfer of technology. Permission to invest . . . would be granted without regard to the existence of competing Chinese domestic suppliers. Consistent with its obligations under the WTO Agreement and the Draft Protocol, the freedom of contract of enterprises would be respected by China.63

Pursuant to these provisions, then, national and subnational Chinese government entities may not condition approval for investments on technology transfer. Section 7(3) makes clear that China “shall ensure” that “approval for . . . investment” is “not conditioned on . . . the transfer of technology.” Paragraph 203 reiterates this language.

If a complainant can prove that this is happening, the complaint is likely to succeed. The complainant, however, has the burden of proof in WTO dispute settlement. Thus, the task of a complainant is to present sufficient facts to a WTO panel to document the actions of Chinese authorities in conditioning investment approval on technology transfer.

Beyond these specific WTO-plus commitments, there is also a general provision that could apply. As described above, the transparency obligations of GATT Article X include a related provision that requires appropriate administration of a Member’s laws. GATT Article X:3(a) provides, “Each (Member) shall administer in a uniform, impartial and reasonable manner all its laws, regulations, decisions and rulings of the kind described in paragraph 1 of this Article.” Under this provision, a successful claim would need to show that China’s actions constitute the “administration” of particular laws, regulations, etc. Then, the claim would need to persuade a panel that the administration of the laws, regulations, and the like has been done in a manner that is not “uniform, impartial and reasonable.” All three requirements could be the basis for a claim, although “impartial” and “reasonable” would perhaps be the easiest to satisfy.

Recently, both the United States and the EU filed requests for consultations with regard to certain Chinese measures on intellectual property protection. For its part, the United States did not challenge any measures directly related to forced technology transfer. Rather, it focused on licensing contracts related to intellectual property and how they discriminate against foreign patent holders and fail to provide adequate protection in accordance with the TRIPS Agreement.64 While the provisions cited here do result in technology transfer against companies’ will, the specific action of forced technology transfer in the process of joint ventures is not referred to in the complaint. Along the same lines, but slightly different, the EU, in its request, included a challenge to China’s application of its laws designed to “induc[e] the transfer of foreign technology to China,” which it alleged was in violation of China’s obligation to provide “impartial and reasonable application and administration of its laws” under GATT Article X:3(a) and Paragraph 2(A)2 of the Accession Protocol.65 However, the EU did not invoke Section 7(3), even though it appears to be the provision that covers this issue most directly.

Subsidies

One of the most frequently raised concerns about Chinese trade practices is the Chinese government’s provision of subsidies to both state-owned enterprises and private companies. These subsidies are offered through a variety of programs, including the Made in China 2025 initiative and its specific implementing measures. Fortunately, the WTO has extensive and detailed rules on subsidies that can be used to challenge China’s behavior. WTO Members have brought several complaints against Chinese subsidies already, including an ongoing case related to agriculture subsidies (see Appendix 1), and there are additional complaints still to be brought.

The WTO Agreement on Subsidies and Countervailing Measures (SCM Agreement) deems subsidies to exist when there is a government “financial contribution” (or income/price support) that confers a “benefit.” But simply finding that a subsidy exists is not enough, as not all subsidies violate WTO rules. In terms of the legal obligations, there are two main categories of subsidies in the SCM Agreement: prohibited and actionable.

The “prohibited” category applies to certain particularly trade-distorting subsidies where the subsidies are “contingent” upon either export performance (export subsidies) or the use of domestic over imported goods (domestic content subsidies). These rules are very strict. If a subsidy meets the terms of either of these, it violates the rules without any need to show an effect on the foreign competitor, and there is a shorter time frame for the offending government to come into compliance when it is found to be providing these subsidies. Thus, for a program such as Made in China 2025, to the extent that any of the subsidies are contingent upon export performance or the use of domestic content, they are in violation of WTO obligations.

Importantly, a de facto connection between the subsidy and export or domestic content will be sufficient. To take an example, there have been reports that China is using subsidies to give an advantage to domestic makers of batteries that are being used in electric vehicles. According to an article in the Wall Street Journal: “Foreign batteries aren’t banned in China, but auto makers must use ones from a government-approved list to qualify for generous [electronic vehicle] subsidies. The Ministry of Industry and Information Technology’s list includes 57 manufacturers, all of them Chinese.”66

For those unfamiliar with WTO rules, this situation may seem too complex to confront. However, the SCM Agreement rules are designed to deal with just this kind of subtle, disguised protectionism. Domestic content subsidies are prohibited even where the contingency is not specified in law.67 If a complainant can show that the connection between the subsidies and the use of domestic goods exists on a de facto basis, the measure will be found in violation. Whether a challenge succeeds will depend on the specific facts of the case. In the electric vehicles example described above, the complainant could look for, inter alia, evidence that the electric vehicle companies that have received subsidies only use batteries on the government lists or that they switched to using the batteries on the lists after the lists were published.

The second category is “actionable” subsidies, which require a showing of an “adverse effect” on a foreign competitor. Under Article 5 of the SCM Agreement, adverse effects may arise through the use of a subsidy when that subsidy results in:

- injury to the domestic industry of another Member

- nullification or impairment of benefits accruing directly or indirectly to other Members under GATT 1994, in particular the benefits of concessions bound under Article II of GATT 1994

- serious prejudice to the interests of another Member68

The “injury” in subparagraph (a) is the same type of injury that is the basis for countervailing duty determinations, as made clear in a footnote to that provision. The “serious prejudice” in subparagraph (c) is defined further in Article 6.3, which identifies the following examples, inter alia, of serious prejudice: displacement or impedance of imports in the market of the subsidizing country or a third-country market; and significant price undercutting or significant price suppression, price depression, or lost sales in the same market. Both of these provisions can provide the basis for claims against subsidies, but they can be challenging to prove, requiring specific evidence of how a particular market has been affected by subsidies. Meeting the burden of proving such claims is especially challenging with respect to China, but past experience shows it can be done.

In addition, subparagraph (b) sets out a potentially broad, but mostly unexplored, type of actionable subsidy claim. There has been a long-standing GATT/WTO remedy for “nullification or impairment” that occurs even in the absence of a violation, generally referred to as a “non-violation” claim. These claims have a higher burden of proof, which makes them difficult to win, and they also have a weaker remedy, which makes winning them less valuable.69 However, by incorporating the nullification or impairment language into SCM Agreement Article 5(b), the WTO drafters may have given this remedy more teeth. There is little existing precedent for such claims, but the language is broad enough to make it worth exploring creative complaints under it.

As an example, China recently introduced tax exemptions and tax reductions for Chinese semiconductor producers, to last for a period of 10 years. For the first two to five years, the taxes will be eliminated completely.70 Subsequently, the taxes will be cut in half, through the 10th year.71

These tax exemptions and reductions clearly constitute “specific subsidies” under Articles 1 and 2 of the SCM Agreement, since they target a particular Chinese industry. The more difficult question is whether they cause “adverse effects to the interest of other Members” under Article 5. There is an argument that, because of their substantial size and the overall design of China’s policies in this sector, the tax exemptions and reductions given by China to its semiconductor industry cause adverse effects under Article 5(b).

According to footnote 12 to Article 5(b), nullification or impairment is “used in this Agreement in the same sense as it is used in the relevant provisions of GATT 1994, and the existence of such nullification or impairment shall be established in accordance with the practice of application of these provisions.” Where a measure is inconsistent with a provision of the GATT, Article XXIII:1(a) applies, and nullification or impairment is presumed. In addition, however, Article XXIII:1(b) gives rise to a cause of action when a member, through the application of a measure, has “nullified or impaired” “benefits” accruing to another Member, “whether or not that measure conflicts with the provisions” of the GATT 1994 (so-called non-violation complaints). The concept of nullification or impairment as an independent basis for a claim, even where there is no violation, has been elaborated in only a few GATT/WTO disputes. One panel offered detailed explanations, and the Appellate Body discussed the issues briefly, which can be summarized as follows.

The text of Article XXIII:1(b) establishes three elements that a complaining party must demonstrate in order to make out a claim under Article XXIII:1(b): (1) application of a measure; (2) a benefit accruing under the relevant agreement; and (3) nullification or impairment of the benefit as the result of the application of the measure.72

In the case of the Chinese tax exemptions and reductions, the application of the measure is clear and the benefits accrue on the basis of the tariff concessions made by China as part of its accession and through further commitments made under the recent Information Technology Agreement (ITA) expansion with regard to semiconductor products.73

The issue here is whether the semiconductor tax exemptions and reductions nullify or impair the benefits of China’s tariff concessions. There is a strong argument that this is the case, due to the fact that the competitive relationship between Chinese chipmakers and U.S. chipmakers has been upset by a very substantial subsidy.

Importantly, in order to prove an Article 5(b) adverse effects claim, there is no need to show lost sales. In this regard, the GATT EEC–Oilseeds I panel concluded: “In the framework of GATT, contracting parties seek tariff concessions. . . . The commitments they exchange in such negotiations are commitments on conditions of competition for trade, not on volumes of trade.”74 Instead of an effect on the volume of trade, a claim of “nullification or impairment” is based on “upsetting the competitive relationship” between domestic and imported products.75 Thus, in the present case, even though the immediate effects of the subsidy on trade flows between the United States and China are not known, the United States may still argue that its producers have been put at a competitive disadvantage relative to their Chinese competitors.

In this case, the benefits in question accrued to the United States on the date of China’s original tariff schedule taking effect after accession, and the date of the ITA expansion being incorporated into China’s schedule. The subsidy (i.e., the tax exemptions and reductions) was announced on March 30, 2018, and was to be effective from January 1, 2018. Since the tax exemptions and reductions were announced on a date subsequent to the tariff concession, the United States is entitled to rely on a presumption that it did not anticipate the introduction of the subsidy and its consequent upsetting of the expected competitive relationship between U.S. and Chinese chipmakers.76

Elaborating on this standard, in EEC–Oilseeds I, a GATT panel considered that nullification or impairment would arise when the effect of a tariff concession is “systematically offset by a subsidy programme”:

The Panel considered that the main value of a tariff concession is that it provides an assurance of better market access through improved price competition. Contracting parties negotiate tariff concessions primarily to obtain that advantage. They must therefore be assumed to base their tariff negotiations on the expectation that the price effect of the tariff concessions will not be systematically offset. If no right of redress were given to them in such a case they would be reluctant to make tariff concessions and the General Agreement would no longer be useful as a legal framework for incorporating the results of trade negotiations.77

This standard was reiterated by a WTO panel in the U.S.–Offset Act dispute: “This would suggest, therefore, that the EEC–Oilseeds panel considered that non-violation nullification or impairment would arise when the effect of a tariff concession is systematically offset or counteracted by a subsidy programme.”78

Examining the semiconductor tax exemptions and reductions under the standard of “systematic offsetting/counteracting” makes clear that the measure has caused nullification or impairment, for the following reasons.

First, the amount of subsidy provided is of great importance. Here the amount of subsidy is the amount of government revenue forgone, which is a complete rebate from a corporate income tax of 25 percent, for two to five years, covering a wide swath of semiconductor manufacturers, plus a 50 percent rebate from income tax through to the 10th year. This large tax rebate serves to completely undermine the promise of lower tariffs, which was a substantial concession that could have been of great benefit to foreign producers, and indicates that the subsidy is counteracting the competitive benefit accruing to the United States under China’s promises.

The U.S. semiconductor industry is the leading global provider of semiconductors and semiconductor manufacturing equipment, accounting for 50 percent and 47 percent shares of the world market, respectively. More than 80 percent of U.S. production is exported, with China its biggest export market. Moreover, China’s growing demand for semiconductors is met mainly by imports, including 56.2 percent from the United States.79 These trade figures make it clear that the United States will be hit hard and put at a competitive disadvantage by these Chinese subsidies relative to what it enjoyed previously. Any competitive edge that U.S. chipmakers had because of tariff reductions on their exports to China will be offset by the Chinese grant of subsidies in the form of tax breaks to domestic Chinese chipmakers.

Secondly, the systematic nature of the Chinese measures can be seen through the broader context of the measure. The Chinese government, motivated by economic and national security goals, has publicly asserted its desire to build a semiconductor industry that is far more advanced than today’s and less reliant on the rest of the world.80 The strategy aims at making China the world’s leader in Integrated Circuit (IC) manufacturing by 2030.81 Therefore, the intention of the Chinese government is clear: it wants to promote domestic production, either for domestic use or export.