The Trump administration wants to increase the size of the U.S. Border Patrol by hiring 5,000 more agents beyond the approximately 20,000 current agents, in addition to filling roughly 1,500 job vacancies. Congress will likely lower the hiring standards for some applicants to help reach the president’s staffing goals. Reports allege that corruption and misconduct are serious personnel problems at Border Patrol, but little direct evidence is available to evaluate the extent of such problems.

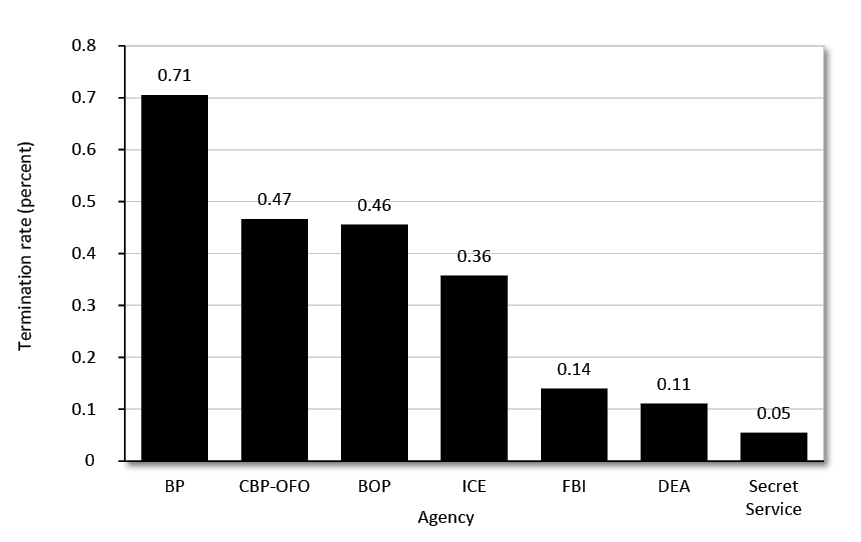

However, data from the Office of Personnel Management reveal that Border Patrol agents are more likely to be terminated for discipline or performance reasons than officers in other large federal law enforcement agencies (those with 5,000 or more officers). From 2006 to 2016, Border Patrol agents were twice as likely to be terminated for disciplinary infractions or poor performance as Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents and 49 percent more likely than Customs and Border Protection officers who work in the Office of Field Operations. Border Patrol agents were 54 percent more likely than guards at the Bureau of Prisons to be terminated for disciplinary infractions or poor performance, 6 times as likely as Federal Bureau of Investigation agents, 7.1 times as likely as Drug Enforcement Administration agents, and 12.9 times as likely as Secret Service agents.

INTRODUCTION

The Trump administration wants to hire 5,000 new U.S. Border Patrol agents to augment the roughly 20,000 current agents, in addition to filling about 1,500 job vacancies.1 Congress will likely lower some hiring standards to help reach that staffing goal.2 Border Patrol corruption and misconduct are likely serious problems, but there is little publicly available direct evidence of the extent of those problems.3

It is virtually impossible to assess the extent of corruption or misconduct in U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP), a subsidiary of the Department of Homeland Security that includes the Border Patrol, because most publicly available information is incomplete or inconsistent. This gap in knowledge is significant because corruption and misconduct erode public trust and can expose the country to serious threats. “Corruption” is the criminal misuse or abuse of an employee’s position; “misconduct” is delinquent behavior that can be, but does not have to be, related to the execution of official duties.

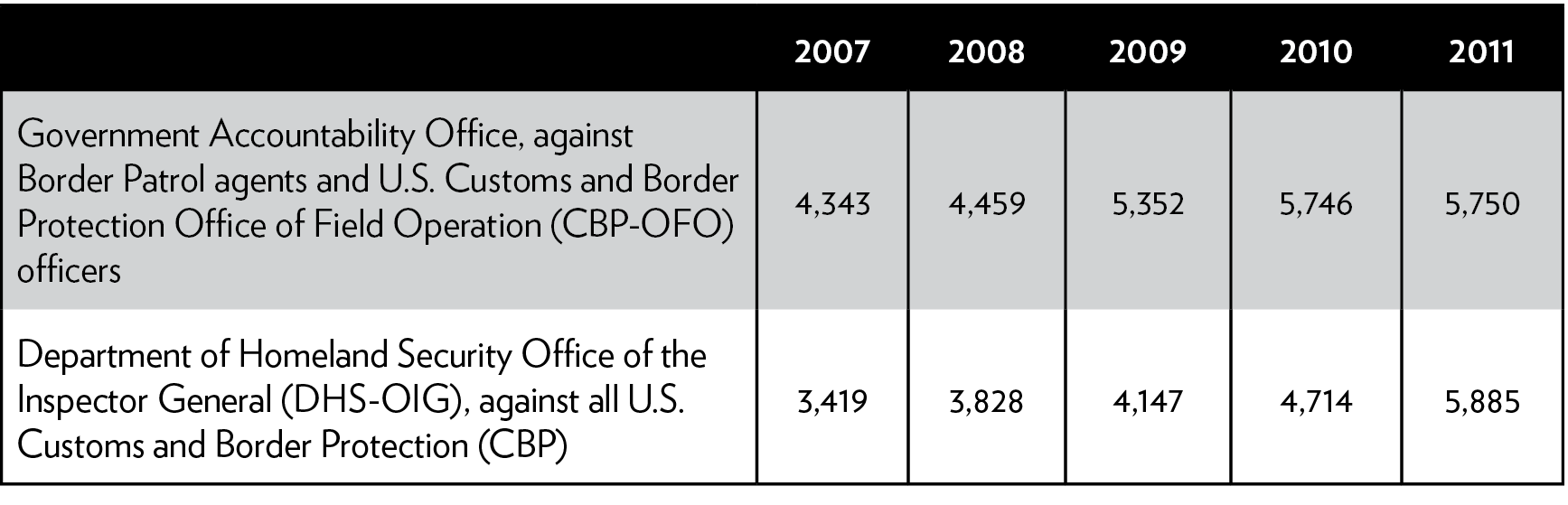

As evidence of poor data, consider a 2012 Government Accountability Office (GAO) report that showed 5,746 allegations of corruption and misconduct against Border Patrol agents and CBP Office of Field Operations (CBP-OFO) officers in 2010.4 However, testimony from the Department of Homeland Security Office of the Inspector General (DHS-OIG) shows 4,714 complaints against all CBP employees in the same year.5 These numbers show that the GAO found more allegations against the Border Patrol and the CBP-OFO, two components of the CBP, than the in-house watchdog of the DHS-OIG recorded against all of CBP.

Despite the high number of allegations recorded by the GAO, a mere 349 complaints were filed against all Border Patrol agents stationed in the southwest border sectors of the United States in 2010, according to the government’s answer to a Freedom of Information Act request (FOIA) filed by the American Immigration Council (see Table 1).6 Another FOIA filed by the same organization uncovered 2,178 complaints of misconduct from January 4, 2012, to October 22, 2015.7 A report by the American Civil Liberties Union of Arizona found only 142 civil rights complaints against Border Patrol agents in two of the nine southwest border sectors from 2011 to 2014.8 Corruption conviction data are just as incomplete or inconsistent. The answer to a FOIA filed by the Immigration Reform Law Institute revealed that just 158 CBP employees that 358 convictions were a result of investigations in CBP.9 The latter number includes both CBP employees and people from outside the agency who participated in their corruption or misconduct. To add more confusion, the GAO reported 2,314 indictments or arrests of CBP employees for corruption or misconduct from 2005 through 2012.10

Table 1

Source: U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO), “Border Security: Additional Actions Needed to Strengthen CBP Efforts to Mitigate Risk of Employee Corruption and Misconduct,” GAO-13-59 December 2012, pp. 12–13; Charles K. Edwards, acting inspector general, U.S. Department of Homeland Security, Testimony before the Subcommittee on Government Organization, Efficiency, and Financial Management, House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform, 112th Cong., 2nd sess., August 1, 2012, https://www.oig.dhs.gov/assets/TM/OIGtm_CKE_080112.pdf.

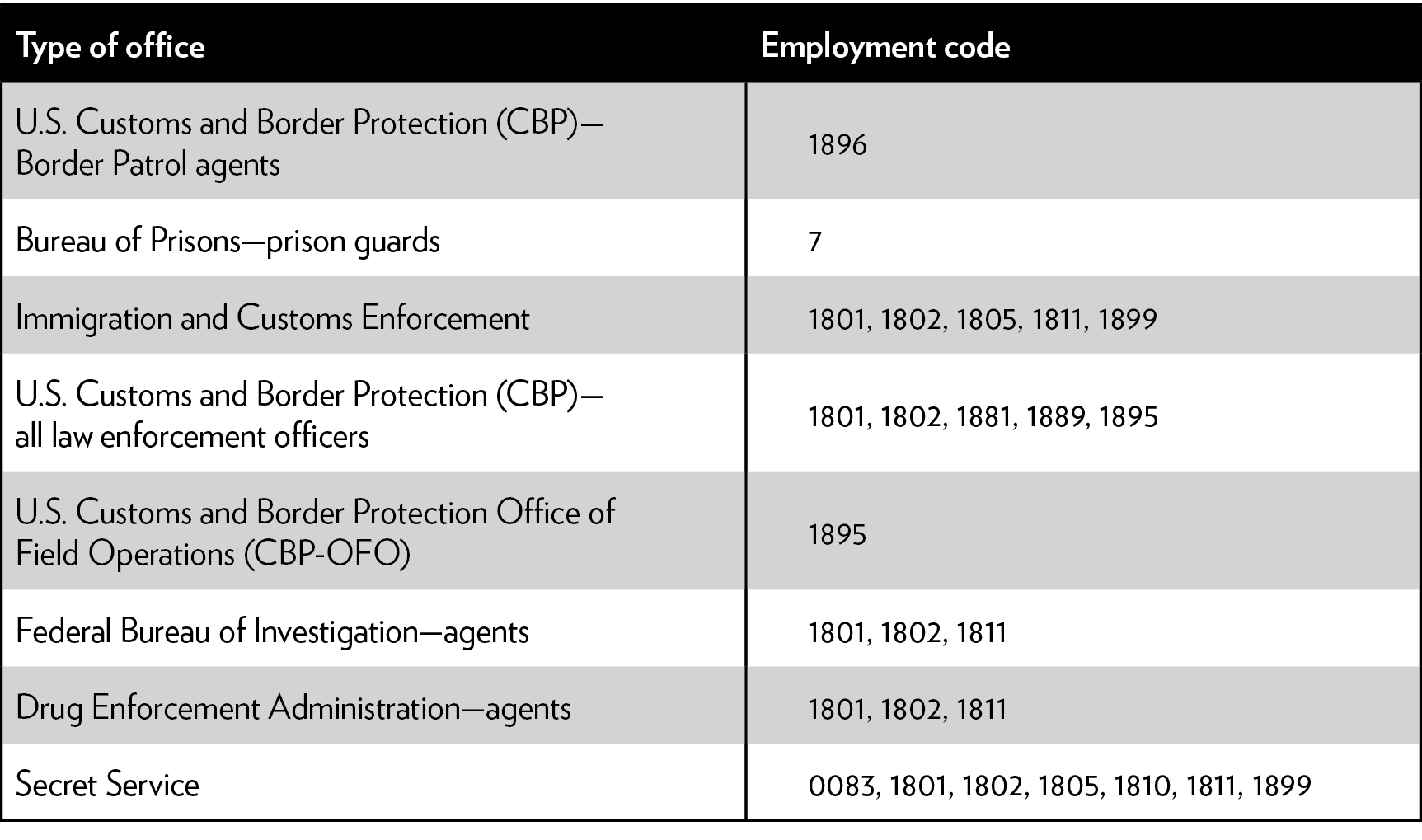

One way to address this confusion is to look at U.S. Office of Personnel Management (OPM) data that indicate serious discipline or performance issues in CBP and Border Patrol. Although the termination rate for performance or discipline is not a direct measure of corruption or misconduct, it does include former employees who were fired for those and other reasons if the government records it properly. Terminations for discipline and performance issues indicate personnel problems at Border Patrol that are related to and even extend beyond misconduct and corruption.

DISCIPLINE AND PERFORMANCE TERMINATIONS IN THE BORDER PATROL

OPM records the total number of federal employees per agency, their specific occupations, the number of separations for each year, and the reason for each separation.11 Termination for disciplinary or performance issues is “based on misconduct, delinquency, suitability, unsatisfactory performance, or failure to qualify for conversion to a career appointment. [This] [i]ncludes those who resign upon receiving notice of action based on performance or misconduct.”12

Figure 1

Discipline or performance termination rate for federal law enforcement officers, 2006–2016

Sources: Office of Personnel Management, “FedScope Separations Cube, Fiscal 2006–2016”; and Office of Personnel Management, “FedScope Employment Cube, Fiscal Years 2006–2016.”

Note: BOP = Bureau of Prisons; BP = Border Patrol; CBP-OFO = Customs and Border Protection Office of Field Operations; DEA = Drug Enforcement Administration; FBI = Federal Bureau of Investigation; ICE = Immigration and Customs Enforcement.

The Border Patrol agent termination rate for discipline or performance is much higher than for law enforcement officers at other large federal law enforcement agencies (Figure 1).13 From 2006 through 2016, Border Patrol agents were twice as likely to be terminated for discipline or performance as Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agents and 49 percent more likely than CBP-OFO officers. Border Patrol agents were 54 percent more likely than guards at the Bureau of Prisons to be terminated for discipline or performance, 6 times as likely as Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) agents, 7.1 times as likely as Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) agents, and 12.9 times as likely as Secret Service agents. The 2006–2016 termination rate for Border Patrol agents was 2.2 times greater than the rate for all other federal law enforcement officers. The termination rate for Border Patrol agents was 2.8 times greater than the rate for federal law enforcement officers who do not enforce immigration laws.

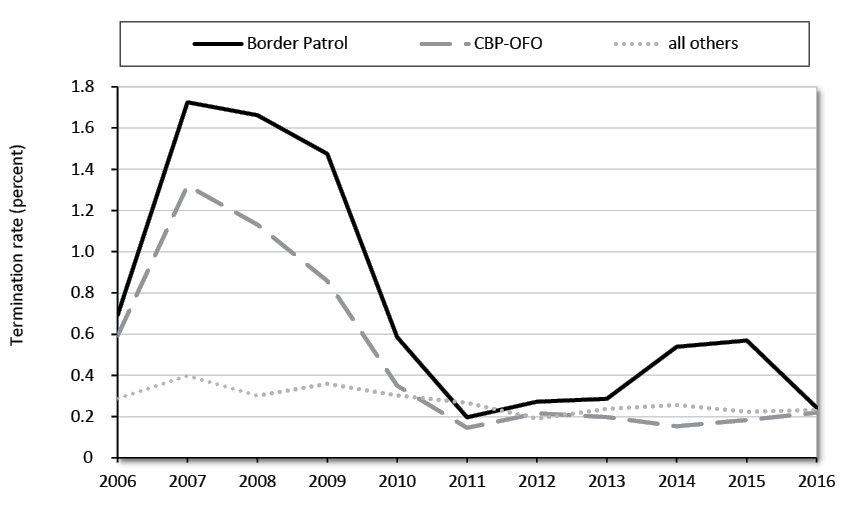

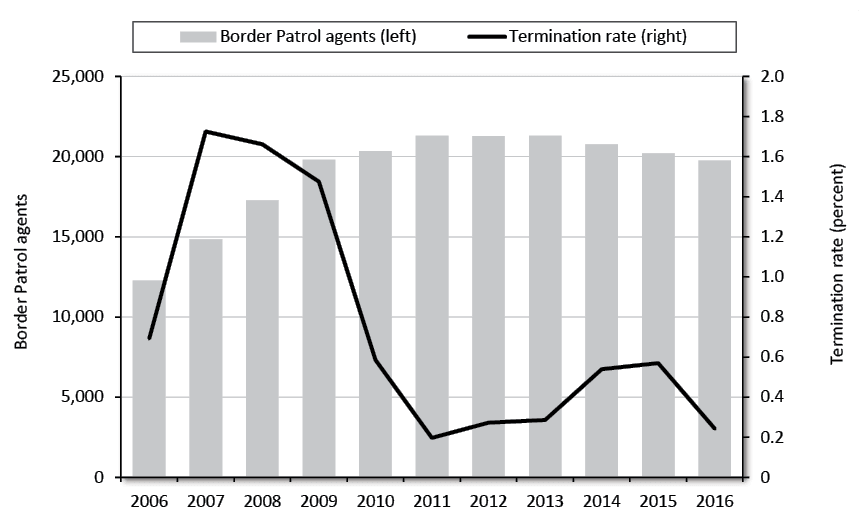

With the exception of 2011, in all years between 2006 and 2016 Border Patrol agents were more likely to be terminated for discipline and performance issues than were law enforcement officers from the other federal law enforcement agencies (Figure 2). Although the initial increase in the Border Patrol termination rate coincides with the surge in the number of new agents, it fell after 2007 and then rose after 2011. Yet, the number of agents continued to climb through much of that period (Figure 3). The termination rate peaked at 1.73 percent in 2007, dipped to 0.20 percent in 2011, and then surged to 0.57 percent in 2015 before coming back down to 0.24 percent in 2016.

Only 33.9 percent of all CBP employees were Border Patrol agents from 2006 to 2016, but they account for 49.4 percent of all CBP terminations for discipline and performance.14 The Border Patrol’s termination rate may actually undercount the extent of personnel problems. From 2006 to 2016, only 26 percent of CBP employees convicted or charged with corruption were actually terminated while 67 percent resigned according to data released by the Immigration Reform Law Institute.15

Figure 2

Termination rate for federal law enforcement officers by component or agency, 2006–2016

Note: CBP-OFO = Customs and Border Protection Office of Field Operations.

Figure 3

Number of Border Patrol agents and termination rate, 2006–2016

Source: Office of Personnel Management, “FedScope Separations Cube, Fiscal Years 2006–2016”; and Office of Personnel Management, “FedScope Employment Cube, Fiscal Years 2006–2016.”

OPM rules specify that government employees who resign upon receiving notice of legal action based on performance or misconduct are to be recorded as terminations.16 It is unclear whether the Immigration Reform Law Institute data are complete, whether they accurately describe how the employment of those CBP employees ended, or both. Adding further confusion, in 2015 CBP reported 7,920 disciplinary outcomes for CBP employees but only 3.4 percent were terminated and 83 employees resigned or retired before disciplinary action.17

The Border Patrol termination rate in-creased 2.4 fold from 2006 to 2008, while the number of agents climbed by only 41 percent. Meanwhile, the termination rate for CBP-OFO officers almost doubled while their numbers increased by only 9.7 percent. From 2006 to 2016, the termination rate for Border Patrol agents and CBP-OFO officers is highly correlated. Because Border Patrol and CBP-OFO were components of the same agency, it is likely that the same factors that influenced the termination rates for Border Patrol agents also influenced the termination rates for CBP-OFO officers.

THE SOURCE OF THE BORDER PATROL’S PERSONNEL PROBLEMS

The high termination rate at the CBP and the Border Patrol indicates serious personnel problems, which could be caused by the same institutional deficiencies that incentivize corruption and misconduct. The first potential deficiency is that understaffed and disorganized internal affairs departments have overlapping investigatory authority and document cases poorly. If that is the case at the CBP, it is difficult to both monitor agents and to quantify the extent of misconduct and corruption. The second potential deficiency is the rapid and recent expansion of Border Patrol agents.18 Initially, a high relative termination rate can be a sign of effective internal affairs, but the Border Patrol has had high termination rates for years. An effective internal affairs operation boosts terminations in the short run through better detection of performance and discipline problems, but the rates should eventually fall as internal affairs begins to deter such behavior.

At CBP, three different offices in DHS share competing and overlapping internal investigative authority, and this poor organization hampers internal affairs investigations. The Office of the Inspector General of the Department of Homeland Security (DHS-OIG), which oversees the entire department, has the power to investigate any case involving a CBP employee. If DHS-OIG declines to investigate, then the Immigration and Customs Enforcement Office of Professional Responsibility (ICE-OPR) can review the case and investigate. If both DHS-OIG and ICE-OPR decline to pursue a case, then CBP’s own internal affairs body—the Office of Professional Responsibility (CBP-OPR)—can investigate.19 And before August 2014, CBP-OPR could only review cases for administrative violations and did not have the authority to investigate criminal misconduct.20

These three offices also do not consistently share information or necessarily cooperate with independent investigatory agencies such as the FBI.21 Ronald Hosko, former assistant director of the FBI’s criminal investigative division (which also investigates government corruption), described DHS-OIG as “a troubled place” that regarded “sharing information as misconduct.” He added that DHS-OIG “fought us at every turn. I believe it was a deliberate attempt by senior people in DHS and in the inspector general’s shop to avoid cooperating with the FBI.”22

CBP’s Joint Intake Case Management System (JICMS) is supposed to be a central clearinghouse for allegations of misconduct and corruption, but it does not include all allegations made by the DHS-OIG, FBI, ICE, or other law enforcement agencies because these agencies track their cases in different databases.23 Additionally, JICMS did not identify excessive use of force allegations and other types of misconduct.24 CBP further complicates this mess by distinguishing between “mission-compromising” and “non-mission-compromising” corruption.25 The former includes drug and immigrant smuggling and the latter includes sexually assaulting detainees and murder.26 CBP also changed the definition of “complaints” in a way that reduces the number of excessive force complaints against Border Patrol officers.27

Corrupted investigators could also make the data suspect. After the release of the previously mentioned GAO report, at least four corruption investigators in DHS-OIG’s McAllen Field Office in Texas were convicted of falsifying documents related to criminal investigations of CBP corruption.28 And additional evidence shows that CBP-OPR agents coached Border Patrol agents accused of misconduct on how to avoid prosecution.29 How many others have escaped detection and how many cases they may have disrupted over the years may never be known. James Tomsheck, former head of CBP-OPR, said that it is “conservative to estimate that 5 percent of the [Border Patrol] force” is corrupt.30

Many argue that misconduct and corruption in CBP and Border Patrol originated with the rapid hiring of new Border Patrol agents as the patrol doubled its size between 2002 and 2010.31 The number of CBP-OFO officers barely expanded, but their termination rate is highly correlated with that of Border Patrol agents. That correlation suggests that the rapid hiring of Border Patrol agents is not responsible for the high termination rate.

At the same time as the hiring surge, Congress reorganized numerous federal agencies in response to 9/11. The Border Patrol was designated as a component agency inside CBP, which was a new agency within the newly created cabinet-level Department of Homeland Security.32 Previously, the Border Patrol had been part of the Immigration and Naturalization Service. The reorganization left the CBP with no internal affairs investigators because they had been transferred to ICE in 2003.33 CBP is the largest law enforcement agency in the United States but it has struggled to rebuild its internal affairs capacity since the reorganization.

In fact, CBP-OPR is tiny relative to other law enforcement internal affairs agencies.34 In 2015, it had 218 internal affairs investigators for a workforce of about 60,000 employees, including over 47,000 law enforcement officers, a ratio of 271 to 1.35 By contrast, the New York Police Department (NYPD) has one internal affairs investigator for about every 65 sworn officers, and the older internal affairs division at Customs before the 2003 reorganization had one internal affairs investigator for every 136 employees.36 The CBP Integrity Advisory Panel, a body that made recommendations in 2016 to ensure agency accountability, said that CBP should have approximately 550 to 565 full-time internal affairs investigators.37 It would require 729 internal affairs investigators if it were to have the same ratio of law enforcement officers to investigators as the NYPD.

IMPROVING BORDER PATROL DISCIPLINE AND PERFORMANCE

Border Patrol agents have unique powers that other law enforcement agents do not, such as the power to conduct checkpoint stops without reasonable suspicion and to act without fulfilling warrant requirements within 100 miles of any land or maritime border.38 Therefore, Border Patrol agents should be more tightly monitored to reduce discipline and performance problems as well as to better measure, and eventually reduce, misconduct and corruption. The following reform recommendations will help achieve these goals.

Establish a Border Patrol Hiring Freeze

Congress should not increase the number of Border Patrol agents until CBP has fully implemented every recommendation of the CBP Integrity Advisory Panel. The most critical recommendation is hiring enough CBP-OPR investigators so that the office is both entirely operational and has substantially reduced its backlog of cases.39 As previously mentioned, of the about 60,000 CBP employees, about 47,000 of them are law enforcement officers. CBP-OPR should have at least the same degree of internal affairs oversight as the NYPD, which would require 729 full-time investigators or 1 for every 65 CBP law enforcement officers.40 The Trump administration’s 2018 budget request asks for an additional 60 (35 full-time equivalent) CBP-OPR investigators, which is not enough to correct the ratio, especially if the proposed 5,000 additional Border Patrol agents are hired alongside them.41

Reorganize Internal Affairs at DHS

All three internal affairs offices that can investigate the CBP and the Border Patrol—DHS-OIG, ICE-OPR, and CBP-OPR—need to have clear jurisdictions. Specifically, they must be either reorganized or combined to form a more effective internal affairs group. The Homeland Security Studies and Analysis Institute wrote: “The reliance upon external organizations for CBP’s internal corruption investigations contravenes the conventional federal law enforcement model for internal affairs. That model calls for the placement of the internal investigative functions within the agency that bears the strongest institutional interest in deterring and detecting corrupt behavior. The Secret Service, Transportation Security Administration, Coast Guard, and ICE maintain internal criminal investigative capabilities within their respective organizations. CBP, which operates in a high threat and corruption prone border environment, requires these same capabilities.”42

Increase CBP-OPR Accountability and Improve Border Patrol Culture

CBP-OPR should be reorganized, fully staffed, and incentivized so that it can deter and detect misconduct and corruption.43 To ease CBP-OPR’s vital task, Border Patrol agents need to cooperate with investigators rather than cover up or manage misconduct outside of official channels.44 This requires breaking the “code of silence” or “Green Code”—the unofficial agency norm of refusing to do or say anything that could incriminate another Border Patrol agent.45 Border Patrol agents who fail to report misconduct or corruption should be terminated, while those who do report it should be rewarded. Mandatory body cameras for all Border Patrol agents would help create a culture of honesty.

Increase GAO Audits

The GAO should frequently audit CBP-OPR to guarantee that its officials are faithfully performing their duties. In addition, the GAO should employ a Forensic Audits and Investigative Services (FAIS) team that focuses on fraud, waste, and abuse to expose Border Patrol corruption and misconduct.46 FAIS should undertake undercover special investigations to help identify misconduct and corruption. Also, the GAO should produce security and vulnerability assessments of CBP and Border Patrol practices to reduce the risk of corruption and misconduct.47 The mere knowledge that FAIS is watching the CBP and the Border Patrol will boost discipline, improve performance, and reduce corruption.

Improve Data

The public should have access to clear and consistently collected data on terminations for discipline, performance, corruption, and misconduct in all federal agencies. The government should publish clear information on misconduct and corruption in CBP and all of its components at regular intervals that includes the number and nature of complaints, investigations, arrests, indictments, terminations, convictions, and all other relevant information that concerns CBP employees. The collection and reporting of these data should be centralized at one office in CBP. Furthermore, OPM should certify that all CBP employees who resign upon receiving notice of action based on performance, discipline, or misconduct are actually recorded as terminations for performance or discipline.

Strengthen Post-Hire Investigations and Polygraph Tests

This process should be identical to the five-year period reinvestigations performed on employees of the FBI, Central Intelligence Agency, Defense Information Agency, and National Security Agency, and should include all on-board CBP employees. Polygraph tests are not inherently effective at detecting liars but the tests do create stress that can expose misconduct or corruption and, in some cases, lead to confessions.48 CBP officials testified in 2010 that they do reinvestigate employees once every five years but that budget shortfalls created a backlog of an estimated 19,000 reinvestigations by the end of that year.49 The CBP should conduct such reinvestigations in a timely and consistent manner.

Impose a 24-Month Evaluation Period for New Border Patrol Agents

Border Patrol agents currently have a 12-month evaluation period during which they can be terminated should disciplinary, performance, or other integrity concerns arise. However, only about 6 of those 12 months cover a new Border Patrol agent in field training while the other 6 months cover classroom training.50 New Border Patrol agents gain full civil service protections after 12 months. That period is too short for supervisors to identify potential integrity issues. The Homeland Security Advisory Committee notes that “one of the most effective anti-corruption measures is to weed out relatively new law enforcement officers before they become problems.”51 OPM has the authority to extend the evaluation period to 24 months for sensitive law enforcement and national security positions and it should do so for Border Patrol agents and other law enforcement officers in the CBP.52 Extending the evaluation period to 24 months before the attachment of full civil service protections allows for observation of about 18 months of fieldwork so that supervisors can better weed out troublesome agents.

Investigate Misconduct Allegations in a Timely Manner

Complex disciplinary and investigation processes at the CBP mean that allegations can languish for long periods of time before they are resolved—151.6 days from incident to decision in 2010.53 The time from the incident to its resolution should be shortened through streamlined organization and the hiring of more investigators.54 CBP employees suspected of corruption should be rotated out of critical security positions until the incident is resolved.

Increase Public Oversight

Many local police departments have civilian review boards to oversee complaints against individual officers. Border Patrol operates continuously in local communities, so those residents should have a direct say in reviewing complaints made by other residents against agents stationed in their communities. Furthermore, all Border Patrol labor contracts should be made public and scrutinized for provisions that inhibit prevention, detection, and punishment of corruption and misconduct. Last, Congress should reduce, curtail, or rescind the Border Patrol’s power to conduct checkpoint stops and conduct searches without warrants within 100 miles of any land or maritime border.55

Table 2

Office of Personnel Management employment codes for federal law enforcement officers

Source: Office of Personnel Management, “Handbook of Occupational Groups and Families,” May 2009, https://www.opm

.gov/policy-data-oversight/classification-qualifications/classifying-general-schedule-positions/.

CONCLUSION

The termination rate of Border Patrol agents for discipline and performance is greater than for law enforcement officers at other federal law enforcement agencies. Even worse, the termination rate for discipline and performance reported in this analysis may be an underrepresentation of personnel problems at Border Patrol. A high relative termination rate could be a sign of effective internal affairs but not in the case of Border Patrol, which is inadequately overseen. If the recommendations made here are enacted, Border Patrol termination rates should rise initially before falling, as deterrence replaces detection as the primary means of reducing personnel problems. Congress should seek to remedy these serious personnel problems in the federal government’s largest law enforcement agency before hiring new agents or further lowering hiring standards.

NOTES

- Department of Homeland Security (DHS) Office of Inspector General, “Special Report: Challenges Facing DHS in Its Attempt to Hire 15,000 Border Patrol Agents and Immigration Officers,” OIG-17-98-SR, July 27, 2017, p. 2; Stephen Dinan, “Panel Advances Polygraph Waiver for Border Patrol, Could Speed Hiring for Thousands of Agents,” Washington Times, May 17, 2017, http://www.washingtontimes.com/news/2017/may/17/panel-advances-polygraph-waiver-border-patrol-coul/; Kevin K. McAleenan,“Request for Approval: Executive Order Hiring Surge Plan,” Memorandum for the Deputy Secretary, U.S. Customs and Border Protection, February 17, 2017, p. 6.

- Eric Katz, “Senate Panel Clears Reform to Speed Hiring of Some Border Agents,” Government Executive, May 17, 2017, http://www.govexec.com/management/2017/05/senate-panel-clears-reform-onboard-some-border-agents-more-quickly/137930/.

- Andrew Becker, “Crossing the Line: Corruption at the Border,” The Center for Investigative Reporting, August 14, 2014, http://bordercorruption.apps.cironline.org/.

- U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO), “Border Security: Additional Actions Needed to Strengthen CBP Efforts to Mitigate Risk of Employee Corruption and Misconduct,” GAO-13-59, December 2012, p. 9. CBP-OFO officers enforce immigration and customs rules at ports of entry. Border Patrol enforces those rules between ports of entry.

- GAO, “Border Security,” pp. 12–13; Charles K. Edwards, acting inspector general, U.S. Department of Homeland Security, Testimony before the Subcommittee on Government Organization, Efficiency, and Financial Management, House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform, 112th Cong., 2nd sess., August 1, 2012, https://www.oig.dhs.gov/assets/TM/OIGtm_CKE_080112.pdf.

- Daniel E. Martinez, Guillermo Cantor, and Walter A. Ewing, “No Action Taken: Lack of CBP Accountability in Responding to Complaints of Abuse,” Special Report, American Immigration Council, May 2014, p. 4.

- Guillermo Cantor and Walter A. Ewing, “Still No Action Taken: Complaints against Border Patrol Agents Continue to Go Unanswered,” Special Report, American Immigration Council, August 2017, p. 7.

- James Lyall, Jane Yakowitz Bambauer, and Derek E, Bambauer, “Record of Abuse: Lawlessness and Impunity in Border Patrol’s Interior Enforcement Operations,” American Civil Liberties Union of Arizona, October 2015, p. 5.

- Lana Shadwick, “New Data Challenge Left’s ‘Lawless’ Border Patrol Conspiracy Theory,” Breit-

bart, December 29, 2016, http://www.breitbart.com/texas/2016/12/29/new-data-challenge-lefts-lawless-border-patrol-conspiracy-theory/. - Edwards, Testimony before the Subcommittee on Government Organization, Efficiency, and Financial Management.

- GAO, “Border Security,” p. 10.

- A “separation” is when a federal worker’s employment with the government ends. OPM records a cause for each separation. Such causes include retirement, resignation, termination for discipline or performance, and others. For simplicity’s sake, this analysis uses the word “termination” to mean a separation for discipline or performance.

- Office of Personnel Management, “FedScope Separations Cube, Fiscal Year 2015,” p. 14.

- “Large” is defined as an agency that had at least 5,000 law enforcement officers at any time during 2015.

- Author’s calculations, based on data in Office of Personnel Management, “FedScope Separations Cube, Fiscal Years 2006–2016”; and Office of Personnel Management, “FedScope Employment Cube, Fiscal Years 2006–2016.”

- Author’s calculations, based on data in Shadwick, “New Data Challenge Left’s ‘Lawless’ Border Patrol Conspiracy Theory.”

- Office of Personnel Management, “FedScope Separations Cube, Fiscal Year 2015,” p. 14.

- Author’s calculations, based on data in Office of Human Resources Management, “CBP Discipline Overview: Fiscal Year 2015,” May 4, 2017, pp. 2, 5.

- The hiring surge for Border Patrol agents after 9/11 required the lowering of standards and could be responsible for many corruption and misconduct problems since then. However, there is little compelling evidence that more recent hires are actually more likely to be convicted of misconduct or corruption and much evidence that the Border Patrol has always been afflicted with high rates of employee misconduct. Homeland Security Studies and Analysis Institute, “U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) Workforce Integrity Study,” December 15, 2011, p. 28; Stephen Engelberg and Deborah Sontag, “Blind Eye: How the Immigration System Handles Discipline—A Special Report. Behind One Agency’s Walls: Misbehaving and Moving Up,” New York Times, December 21, 1994, http://www.nytimes.com/1994/12/21/us/blind-eye-immigration-system-handles-discipline-special-report-behind-one-agency.html?pagewanted=all&pagewanted=print.

- CBP-OPR was known as CBP Internal Affairs until 2016. For simplicity’s sake, this analysis refers to it as CBP-OPR even when discussing events that occurred when it was known as CBP Internal Affairs.

- Homeland Security Advisory Council (HSAC), “Interim Report of the CBP Integrity Advisory Panel,” June 29, 2015, p. 7; Homeland Security Studies and Analysis Institute, “U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) Workforce Integrity Study,” p. 15.

- HSAC, “Interim Report,” p. 10; Garrett M. Graff, “The Green Monster,” Politico Magazine, November/December 2014, http://www.politico.com/magazine/story/2014/10/border-patrol-the-green-monster-112220?paginate=false; Mark Binelli, “10 Shots across the Border,” New York Times Magazine, March 3, 2016, https://www.nytimes.com/2016/03/06/magazine/10-shots-across-the-border.html.

- Binelli, “10 Shots across the Border.”

- DHS Office of Inspector General, “CBP Use of Force Training and Actions to Address Use of Force Incidents (Redacted),” OIG-13-114 (Revised), September 2013, p. 6.

- Ibid., pp. 5–6.

- Graff, “The Green Monster”; Binelli, “10 Shots across the Border.”

- Ibid.

- Office for Civil Rights and Civil Liberties, “Quarterly Report to Congress, Third and Fourth Quarters, FY 2014,” Department of Homeland Security, February 23, 2014, p. 4.

- GAO, “Border Security”; and “Former Special Agent in Charge of the Department of Homeland Security’s Office of Inspector General Sentenced to More Than Three Years in Prison,” Department of Justice, Office of Public Affairs, December 15, 2014, https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/former-special-agent-charge-department-homeland-securitys-office-inspector-general-sentenced.

- Andrew Becker, “2010 Border Patrol Fatal Shooting Comes under Renewed Scrutiny,” Huffington Post, October 4, 2014, http://www.huffingtonpost.com/andrew-becker/2010-border-patrol-fatal-_b_5643247.html.

- Jeremy Raff, “The Border Patrol’s Corruption Problem,” Atlantic, May 5, 2017, https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2017/05/not-one-bad-apple/525327/.

- Joshua Breisblatt, “Spike in Corruption Followed Last Hiring Surge at CBP and ICE,” American Immigration Council, April 25, 2017, http://immigrationimpact.com/2017/04/25/spike-corruption-followed-last-hiring-surge-cbp-ice/; “U.S. Border Patrol Fiscal Year Staffing Statistics (FY 1992–FY 2016),” U.S. Customs and Border Protection, January 3, 2017, https://www.cbp.gov/document/stats/us-border-patrol-fiscal-year-staffing-statistics-fy-1992-fy-2016.

- GAO, “Border Security,” p. 2; Alan D. Bersin, commissioner, U.S. Customs and Border Protection, U.S. Department of Homeland Security, Testimony before the Ad Hoc Subcommittee on Disaster Recovery and Intergovernmental Affairs of the Senate Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs Committee, 112th Cong., 1st sess., June 9, 2011, https://www.hsgac.senate.gov/subcommittees/disaster-recovery-and-intergovernmental-affairs/hearings/border-corruption-assessing-customs-and-border-protection-and-the-department-of-homeland-security-inspector-generals-office-collaboration-in-the-fight-to-prevent-corruption; and Chad C. Haddal, “Border Security: The Role of the U.S. Border Patrol,” CRS Report for Congress no. 7-5700, Congressional Research Service, August 11, 2010, p. 2.

- HSAC, “Interim Report,” pp. 6–7.

- HSAC, “Interim Report,” pp. 6–7, 9; and DHS Office of Inspector General, “CBP Needs Better Data to Justify Its Criminal Investigator Staffing,” OIG-16-75, April 29, 2016, p. 1.

- DHS Office of Inspector General, “Investigation of DHS Employee Corruption Cases,” Fiscal Year 2015 Report to Congress, November 23, 2015, p. 13.

- DHS Office of Inspector General, “Investigation of DHS Employee Corruption Cases,” Fiscal Year 2015 Report to Congress, November 23, 2015, p. 13; HSAC, “Interim Report,” p. 8n11; and Homeland Security Studies and Analysis Institute, “U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) Workforce Integrity Study,” p. 17n42.

- Homeland Security Advisory Council (HSAC), “Final Report of the CBP Integrity Advisory Panel,” March 15, 2016, p. 11.

- Lori Johnson, “Preserving the Excessive Force Doctrine at Our Nation’s Borders,” Holy Cross Journal of Law and Public Policy 14, no. 89 (2010).

- HSAC, “Final Report,” p. 11.

- Ibid., pp. 11–12.

- Department of Homeland Security, “Congressional Budget Justification,” FY2018, vol. I, p. CBP-O&S-10.

- Homeland Security Studies and Analysis Institute, “U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) Workforce Integrity Study,” pp. 14–15.

- HSAC, “Final Report,” pp. 15–18.

- Graff, “The Green Monster”; Binelli, “10 Shots across the Border”; and Full Measure Staff, “Crossing the Line,” Full Measure News, November 20, 2016, http://fullmeasure.news/news/cover-story/crossing-the-line.

- Homeland Security Studies and Analysis Institute, “U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) Workforce Integrity Study,” pp. 8–9; Jorge A. Vargas, “U.S. Border Patrol Abuses, Undocumented Mexican Workers, and International Human Rights,” San Diego International Law Journal 2, no. 1 (2001); and Andrew Becker, “Border Agency Report Reveals Internal Struggles with Corruption,” The Center for Investigative Reporting, January 29, 2013, https://www.revealnews.org/article/border-agency-report-reveals-internal-struggles-with-corruption.

- Government Accountability Office, “GAO’s Forensic Audits and Investigative Service Team,” GAO WatchBlog, April 24, 2014, https://blog.gao.gov/2014/04/24/introduction-to-gaos-forensic-audits-and-investigative-service-team/.

- Ibid.

- HSAC, “Final Report,” p. 19.

- Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs, Anti-Border Corruption Act of 2010, S. Rep. No. 111-338 (2010).

- Richard M. Stana, director, Homeland Security and Justice Issues, Testimony before the Subcommittee on Management, Investigations, and Oversight of the House of Representatives Homeland Security Committee, 110th Cong., 1st sess., June 19, 2007, http://www.gao.gov/new.items/d07997t.pdf.

- HSAC, “Final Report,” p. 17.

- Ibid.

- Homeland Security Studies and Analysis Institute, “U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) Workforce Integrity Study,” pp. 10–11, 12.

- Ibid., pp. 10–11, 72.

- Jesus A. Osete, “The Praetorians: An Analysis of U.S. Border Patrol Checkpoints Following Martinez-Fuerte,” Washington University Law Review 93, no. 3 (2016).

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.