The Supreme Court has ruled that police officers are allowed to search cars without a warrant if they have probable cause to believe that a person has engaged in some form of criminal activity.94 However, officers are not permitted to routinely search people's cars for weapons, drugs, or contraband "just in case." Searching a suspected criminal's house, in most circumstances, requires police to first obtain a warrant.95

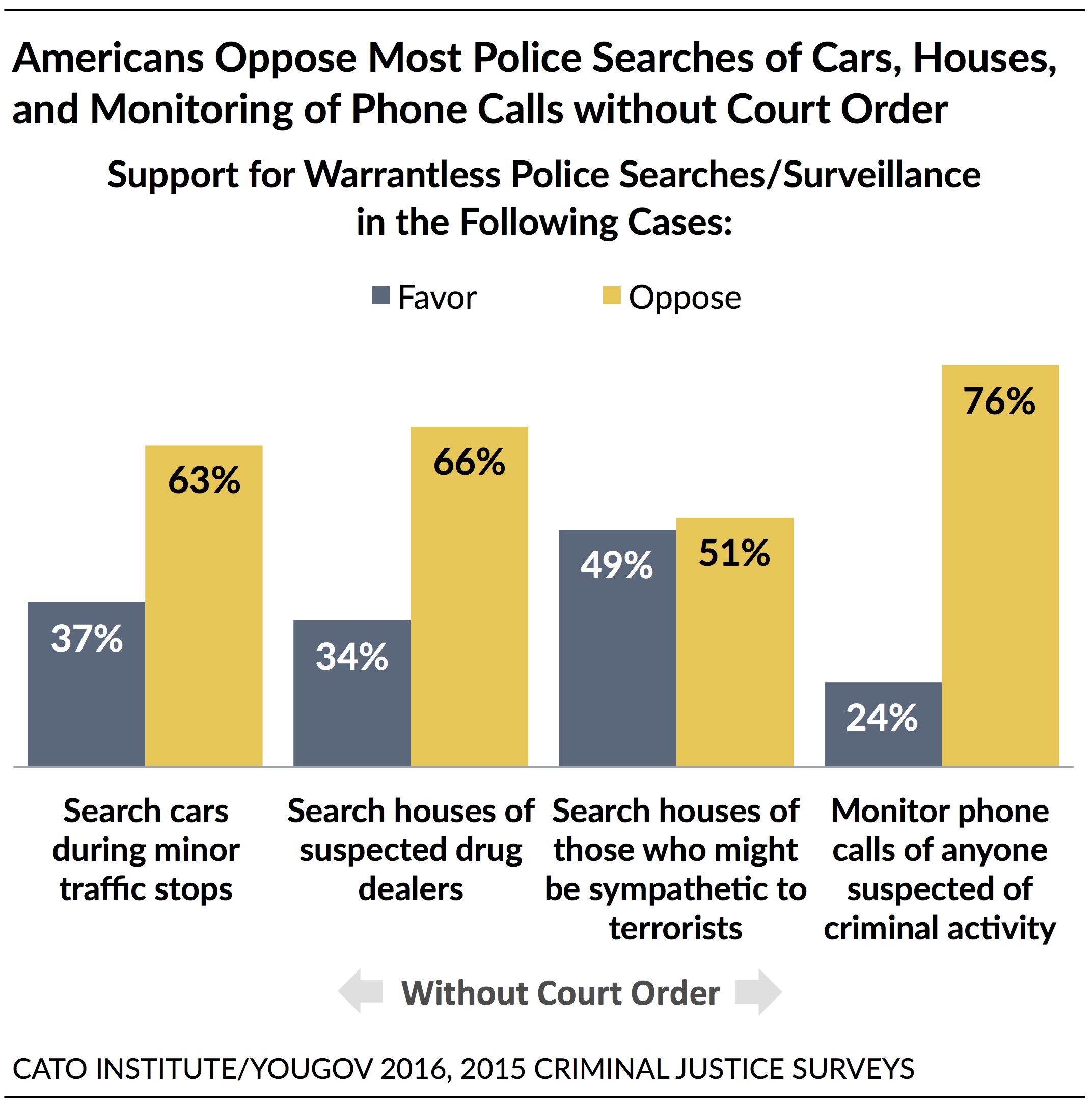

Would Americans tolerate police searches without probable cause or a warrant? The answer is no: majorities think law enforcement ought to meet a higher standard before subjecting even suspected criminals to additional scrutiny.

Vehicle Searches Americans acutely concerned about drug prohibition might support police using minor traffic stops to routinely check cars for illegal drugs and other contraband. Although this practice is unconstitutional, some might reason: if one isn't breaking the law, one should have nothing to worry about.96 Do Americans think police should use minor traffic stops to routinely check cars for illegal activity—just in case?

No. A solid majority of Americans—63%—say police officers should not be allowed to routinely search cars for drugs during minor traffic stops, unless they get a court order. A third say police should take the opportunity to check for drugs even without a court order.

Majorities across demographic and political groups oppose police using minor traffic stops to routinely check cars for drugs. However, African Americans (70%) are more opposed than Hispanics (56%) and Caucasians (64%). Similarly, majorities of partisans oppose such a policy, although Democrats (68%) and non-partisan independents (71%) are more opposed than Republicans (54%). Liberals (18%) and Libertarians (26%) are the least supportive of such a practice, compared to Conservatives (37%) and Communitarians (61%). Communitarians stand out with a strong majority (61%) favoring routine vehicle searches.

Americans who believe the "war on drugs" has been worth the costs to taxpayers and those who strongly oppose legalizing marijuana stand out with majorities (56% and 56% respectively) who say police should use minor traffic stops to routinely search cars for drugs. This data indicate being strongly committed to the Drug War may foster support for unconstitutional practices.

Home Searches What about searching a person's home? If a police officer suspects a person deals drugs, do Americans think police ought to obtain a court order before entering the house to search for drugs or other illegal activity?

Yes. A strong majority 66% of Americans oppose police searching the homes of individuals suspected of dealing drugs without first obtaining a court order. A third say police should not have to get a court order first. This indicates that for most Americans, suspected law-breaking does not justify warrantless searches.

Strong majorities across demographic and political groups agree that police ought to get a warrant before searching a suspected drug dealer's house (including whites (69%, blacks (68%), Hispanics (54%), Democrats (63%), independents (72%), Republicans (62%). However, women are about 15 points more likely than men to approve of such warrantless home searches of suspected drug dealers (41% vs. 26%). Similarly, high school graduates (40%) are about twice as likely as post-graduates (19%) to approve.

Libertarians (81%) and Liberals (79%) are the most opposed to warrantless home searches of suspected drug dealers compared to 70% of Conservatives and 54% of Communitarians. In fact, Communitarians are more than twice as likely as Libertarians and Liberals to support such warrantless searches (46% vs. 20%).97

Americans who strongly oppose legalizing marijuana (47%) are about 20 points more likely than those who strongly support doing so (25%) to favor warrantless searches of suspected drug dealers' homes. Some Americans seem willing to sacrifice rule of law and due process to fight the Drug War. Reformers may wish to keep in mind that those committed to drug prohibition may not respond to constitutional arguments criticizing warrantless searches.

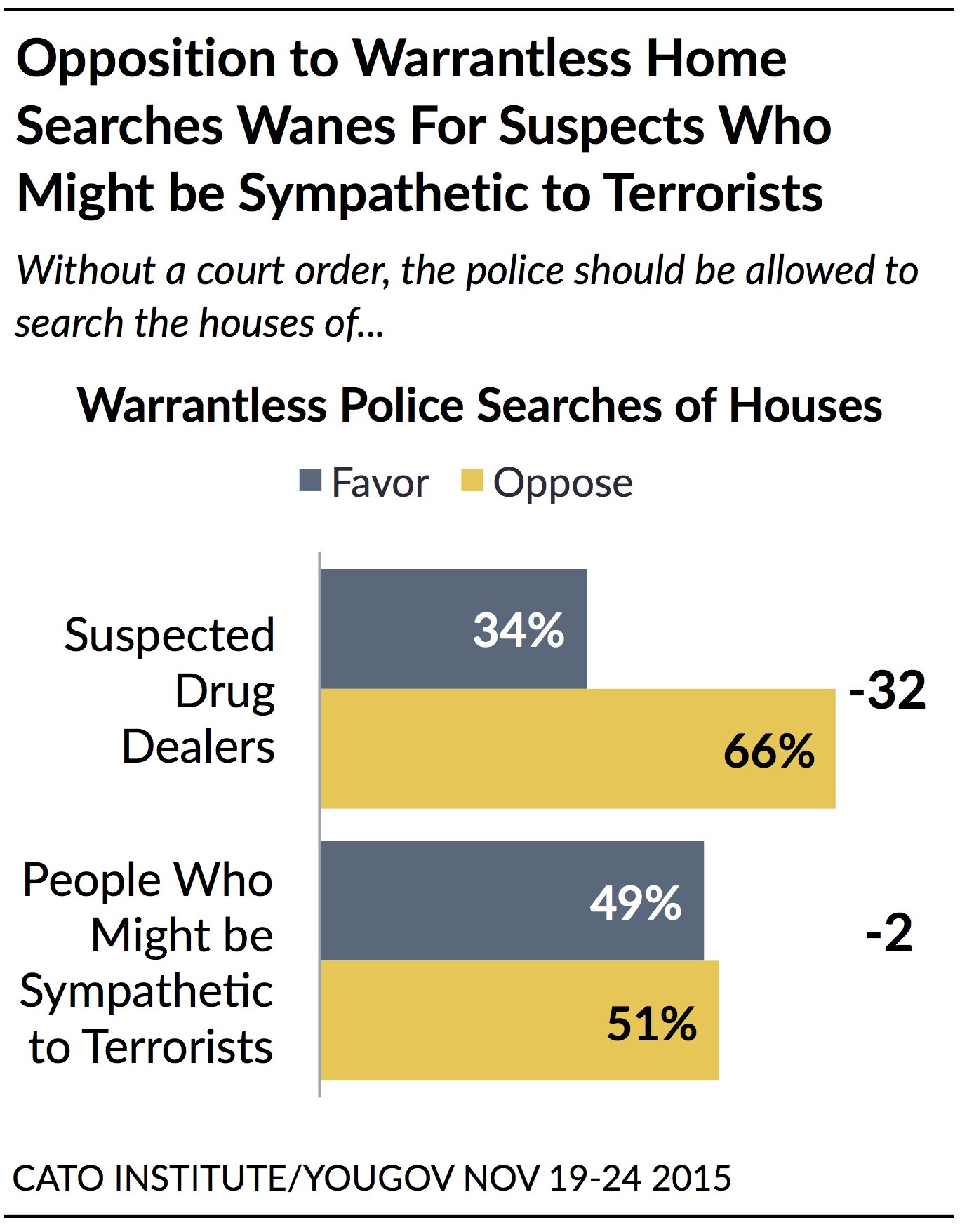

Americans may be willing to make exceptions regarding search warrants depending on their emotional reaction to the suspect. In a survey conducted several days after the November 2015 Paris attacks, 51% said police ought to obtain a court order before searching the home of a person who might be sympathetic to terrorists.98 This share is 15 points lower than the 66% in that same survey who said the police should first obtain a court order before searching the home of suspected drug dealers.

A majority of men (58%), non-evangelicals (54%), college graduates (60%), white Americans (54%) and black Americans (52%) oppose warrantless searches of people's homes who police believe might be sympathetic to terrorists. However, a majority of women (56%), evangelicals (56%), high-school graduates (64%), and Hispanics (63%) favor such warrantless searches. Differences in educational attainment appear to largely underlie the ethnicity gap on this question.

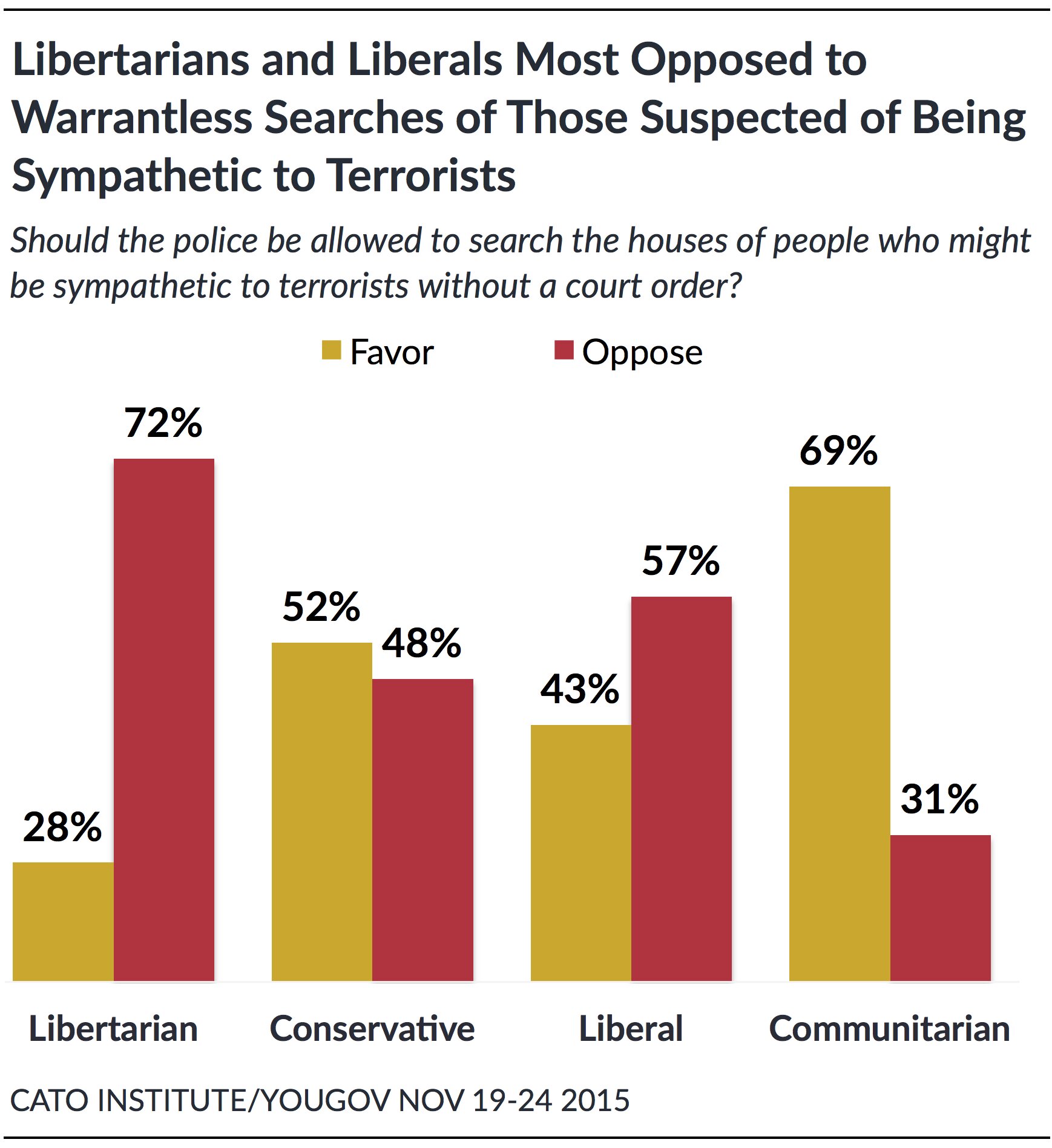

Although partisans largely agree, there are striking ideological differences. Libertarians are most opposed (72%) to warrantless searches of people who police suspect might be sympathetic to terrorists. This share is 15 points higher than Liberals (57%) opposed. In contrast, a slim majority (52%) of Conservatives favor such warrantless searches while 48% oppose. Communitarians stand out as most comfortable with such warrantless searches with 69% in support and 31% opposed.98

Although the United States demands equality before the law, reformers should keep in mind that the public may tolerate disparate treatment depending on their emotional reaction to the suspect.

Interestingly, by June 2016, opposition rebounded to 62% saying the police ought to obtain a court order before searching the home of a person who might be sympathetic to terrorists.

Notes:

94 Probable cause could include contraband in plain view, overt smell of an illegal substance, or if a drug dog identifies drugs.

95 Police may not need a court order to search a house if police have probable cause to believe a crime is contemporaneously being committed, such as they hear gunshots in a house or hear someone screaming for help.

96 This is the "nothing to hide" argument. For instance, consider Sen. Trent Lott's reaction to the debate over the collection of Americans' phone records in 2006: "What are people worried about? What is the problem? Are you doing something you're not supposed to?" "BellSouth Denies Giving Records to NSA," CNN.com, May 15, 2006, http://www.cnn.com/2006/POLITICS/05/15/bellsouth.nsa/. For further discussion see Daniel J. Solove, "'I've Got Nothing to Hide' and Other Misunderstandings of Privacy," San Diego Law Review 44 (2007): 745-772.

97 See Appendix A for an explanation of ideological clusters.

98 Results from the November 2015 Cato Institute/YouGov National Survey, conducted November 19 to 24, 2015.

99 See Appendix A for an explanation of ideological clusters.