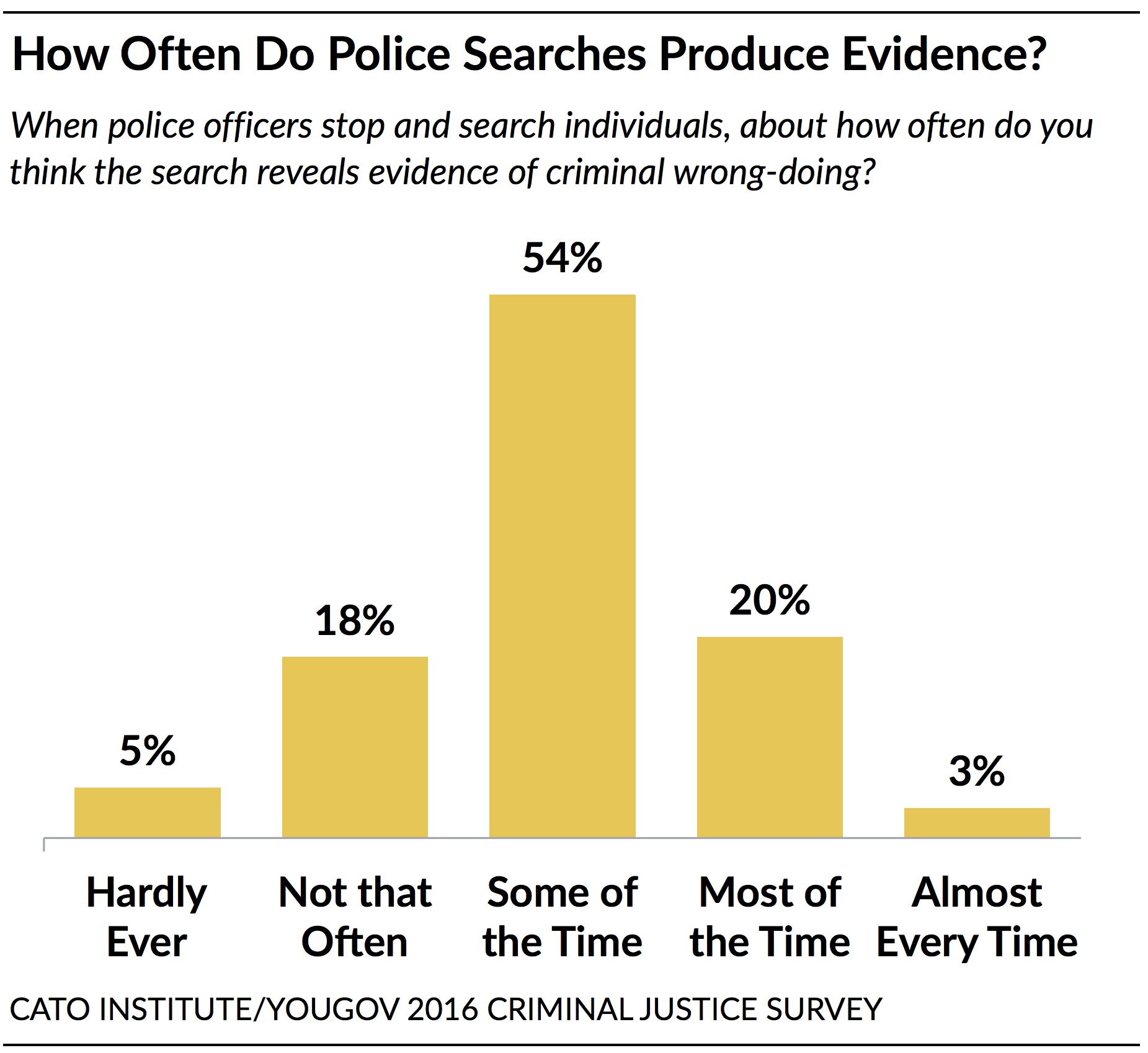

Americans believe that police stops and searches of individuals usually reveal useful information to fight crime. More than three-fourths (77%) of Americans believe police searches reveal useful information at least "some of the time" (54%), including 20% who say "most of the time" and 3% who say "almost every time." Only 23% think police searches rarely yield evidence of criminal wrongdoing, including 18% who say it's "not that often," and 5% who say "hardly ever."

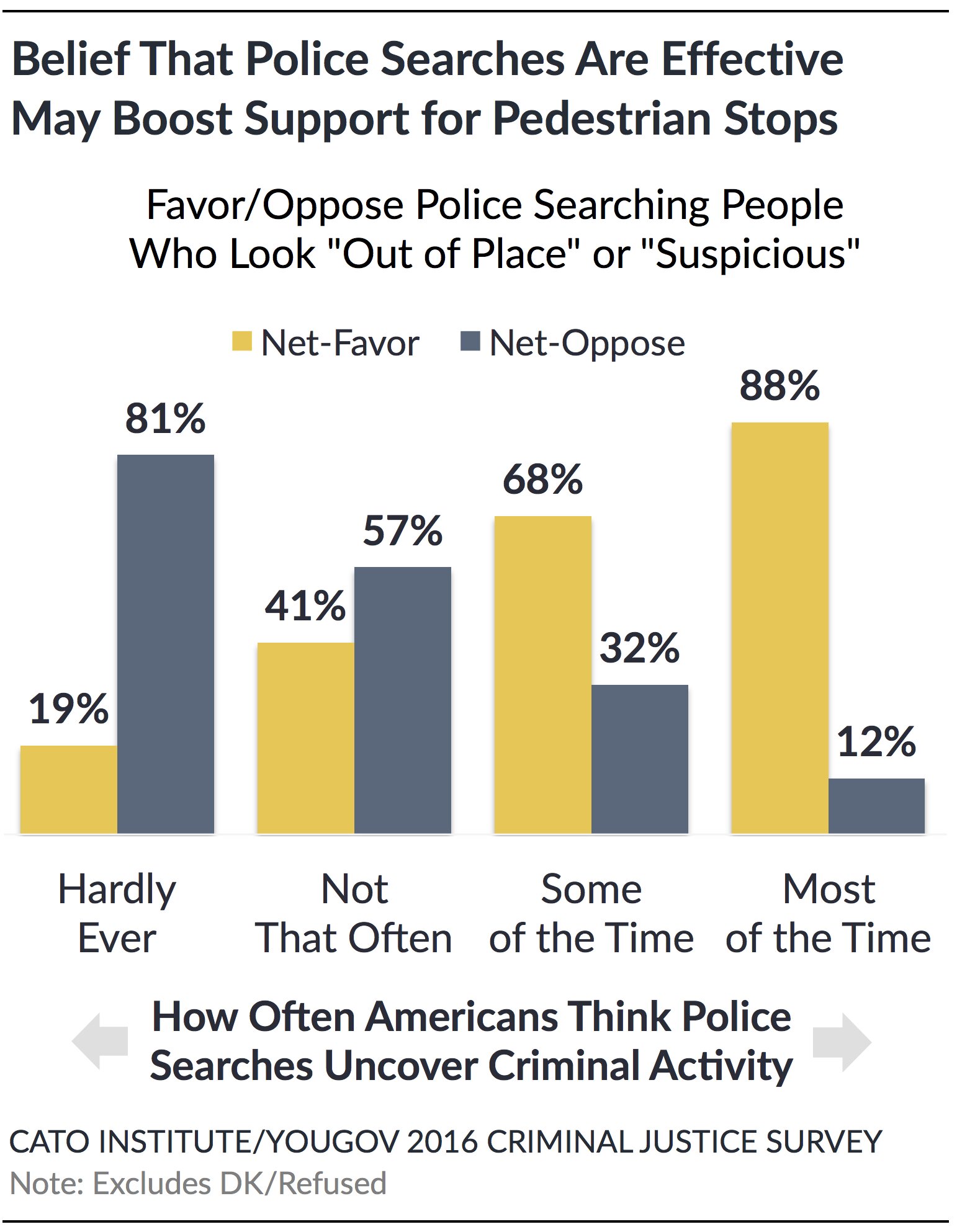

Among those who think searches reveal useful evidence most of the time, 88% favor police conducting searches of people who the officer thinks looks suspicious, while 13% oppose. However among those who think searches reveal evidence "not that often," only 41% support giving police more latitude and 57% are opposed.

In short, Americans appear more likely to allow officers to use greater discretion when deciding whom to stop and search if they believe searches reliably uncover evidence of criminal wrongdoing. However, some research suggests police stops and searches may not be particularly efficacious.93 These data provide some indication that if this were generally known, the public might oppose giving police such latitude in conducting stops and searches.

Notes:

92 There is evidence that pedestrian and vehicle searches may not be very efficacious. For instance, the NYCLU finds that the NYPD's Stop and Frisk program uncovered wrongdoing in about 12% of the over 2 million pedestrian stops since 2010 and Eith and Durose find that about 8.4% of vehicle searches uncovered evidence of criminal activity in 2008. See Christopher Dunn and Sara LaPlante, "Stop and Frisk 2012 NYCLU Briefing," New York Civil Liberties Union, May 2013, http://www.nyclu.org/files/publications/2012_Report_NYCLU_0.pdf. Christine Eith and Matthew R. Durose, Contacts between Police and the Public, 2008, edited by Bureau of Justice Statistics (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Justice, 2011), https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/cpp08.pdf.