| Blackstone's Ratio: Is it more important to protect innocence or punish guilt? |

| When crimes occur, societies often cannot know for certain if a suspect is guilty or innocent. Consequently, societies must grapple with what type of "mistakes" they will tolerate more—sometimes punishing or scrutinizing innocent people or sometimes allowing guilty people go free.73 The American system, grounded in the British Common Law, has long erred on the side of protecting innocence. Thus we presume an accused person's innocence until they are proven guilty. As the preeminent English jurist William Blackstone wrote,"[B]etter that ten guilty persons escape, than that one innocent suffer."74 This principle can also be found in religious texts and in the writings of the American Founders.75 Benjamin Franklin went further arguing "it is better a hundred guilty persons should escape than one innocent person should suffer."76 Other notable historical figures have worried more about punishing the guilty. For instance German chancellor Otto von Bismarck is believed to have remarked: "it is better that ten innocent men suffer than one guilty man escape."77 Che Guevara and 20th century communist movements in China, Vietnam, and Cambodia, also employed similar reasoning. 78 The survey posed dilemma to the American people, asking respondents which of the following scenarios they believe would be worse:

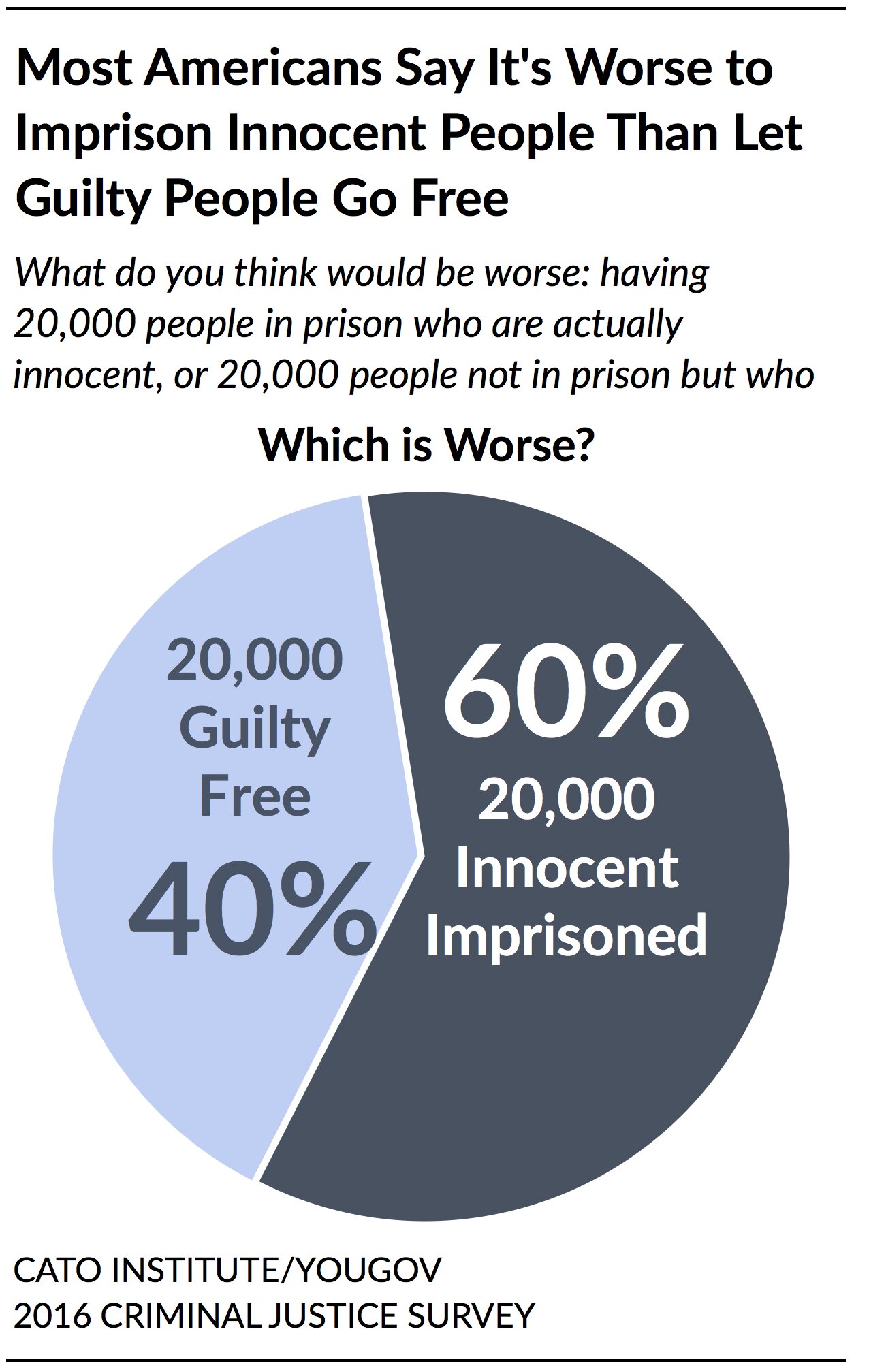

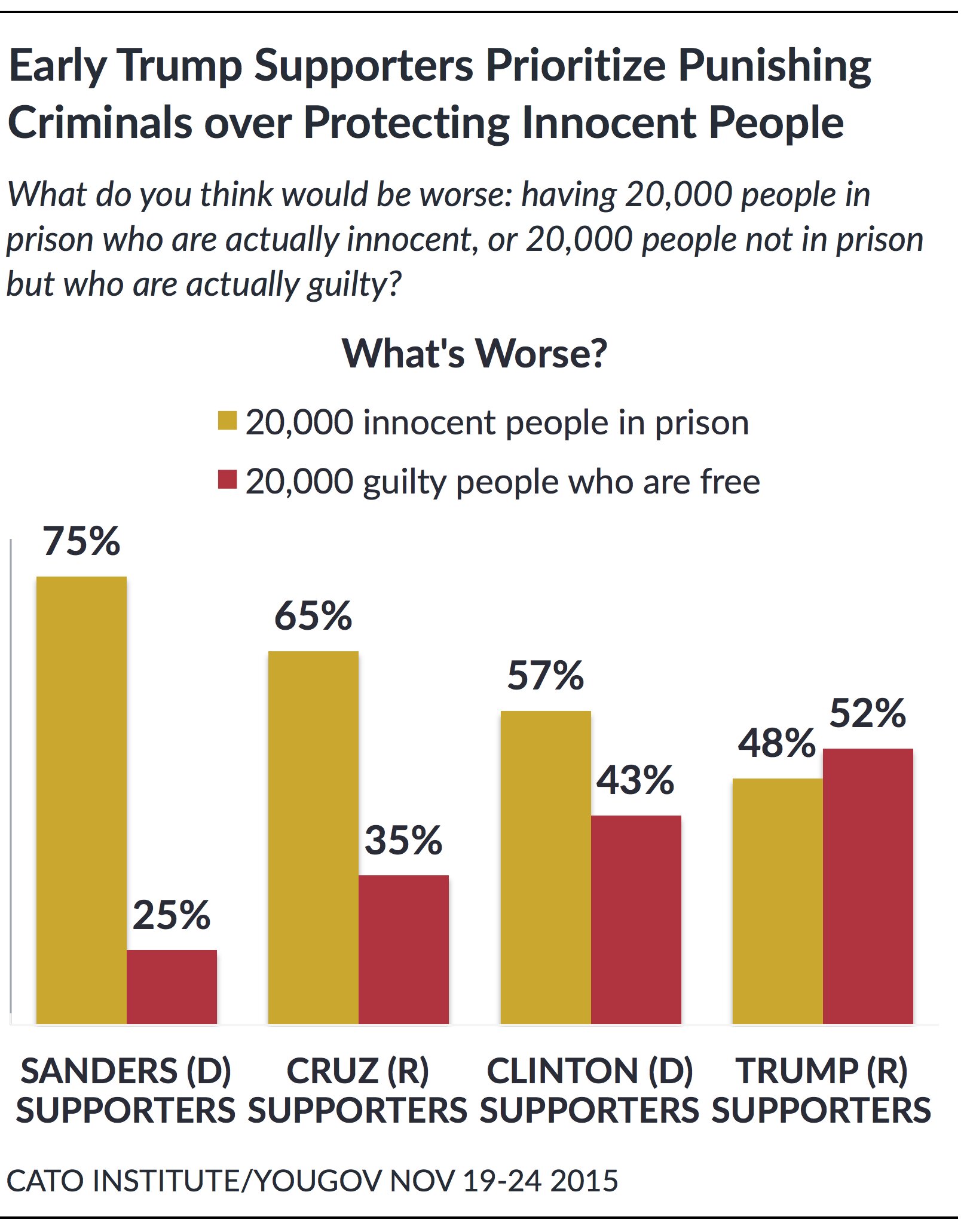

The survey found that a majority (60%) of Americans say it would be worse to have 20,000 innocent people in prison, while 40% say it would be worse to have 20,000 people who are actually guilty but not in prison. Strikingly, Donald Trump's early core supporters (from November 2015) stand out with a majority (52%) who say it's worse to not punish the guilty. They are distinct from other Republican voters. For instance, a majority (65%) of Ted Cruz's early core supporters say it's worse to imprison the innocent.79 People who care more about punishing guilty people also tend to be less concerned about due process. Americans who say it's worse to allow guilty people go free than to imprison innocent people are about 15-30 points more likely to support warrantless police stops and searches in a variety of situations.80 This dilemma (to prioritize protecting innocence or punishing guilt) informs contemporary debates over law enforcement and reform. Take for instance New York City's Stop and Frisk program which failed to uncover wrongdoing in 88% of the over 2 million pedestrian stops since 2010. 81 Was this policy worth it? Observers with the same set of facts have reached dramatically different conclusions.82 Individuals have different value priorities that lead them to prioritize either protecting the innocent or punishing the guilty. Law enforcement reformers across the political spectrum might consider how their audience makes this trade-off. |

Notes:

73 This dilemma is analogous to Type 1 and Type 2 errors found in empirical research. In this case, Type 1 errors would mean convicting innocent people of crimes they didn't commit or subjecting them to added scrutiny despite their innocence, and Type 2 errors would mean failing to convict guilty people of crimes they did commit and allowing them to go free unpunished.

74 Alexander Volokh, "n Guilty Men," University of Pennsylvania Law Review 146 (1997): 173-216.

75 Alexander Volokh, "n Guilty Men," University of Pennsylvania Law Review 146 (1997): 173-216; John Adams made similar arguments in defending British soldiers after the Boston Massacre, "[W]e are to look upon it as more beneficial, that many guilty persons should escape unpunished, than one innocent person should suffer," (p. 176).

76 Benjamin Franklin, "Letter from Benjamin Franklin to Benjamin Vaughn (Mar. 14, 1785)," The Works of Benjamin Franklin 11, ed. John Bigelow (1904), quoted in Alexander Volokh, "n Guilty Men," University of Pennsylvania Law Review 146 (1997): 173-216.

77 John W. Wade, "Uniform Comparative Fault Act," The Forum 14, no. 3 (1979): 379-405.

78 Communists employed similar reasoning during the uprisings in Jiangxi, China in the 1930s: "Better to kill a hundred innocent people than let one truly guilty person go free," and during uprisings in Vietnam in the 1950s: "Better to kill ten innocent people than let a guilty person escape." Phillip Short, Pol Pot: Anatomy of a Nightmare (New York: Henry Holt, 2006), pp. 299, 496. Similarly in Cambodia, Pol Pot's Khmer Rouge adopted a similar policy: "better arrest an innocent person than leave a guilty one free." Henri Locard, Pol Pot's Little Red Book: The Sayings of Angkar Chang Mai (Chiang Mai: Silkworm Books, 2005), pp. 208-209. Maria C. Werlau, "Che Guevara Forgotten Victims," The Free Society Project, 2011, http://cubaarchive.org/home/images/stories/che-guevara_interior-pages_e….

79 Results are from the November 2015 Cato Institute/YouGov National Survey, conducted November 19 to 24, 2015.

80 For instance, roughly 7 in 10 Americans who prioritize protecting the innocent oppose police conducting routine vehicle searches during minor traffic stops or home searches of suspected drug dealers without a court order, while those who prioritize punishing wrongdoing are about evenly divided.

81 NYCLU, "Stop-and-Frisk Data," New York Civil Liberties Union, 2016, http://www.nyclu.org/content/stop-and-frisk-data.

82 For instance, the NYCLU has presented the Stop and Frisk error rate as evidence that the program has over-stepped, while a Breitbart writer touted the exact same set of facts as evidence of the program's success. Milo Yiannopoulos, "Milo Talks Who Illegal Immigration Hurts, and Who Stop & Frisk Helps," YouTube, 2016, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-2qHRMW7284.