Pandemics and epidemics generate some of the largest economic shocks catalogued by economic historians. Beyond the death toll, pandemics make societies poorer through a variety of mechanisms. The infected people who survive outbreaks tend to bear scars that affect their work capacity. Pregnant mothers infected during outbreaks also transmit the consequences in ways that affect their children’s health and schooling abilities. These, in turn, affect the children’s lifetime income. The voluntary measures that affected populations adopt to limit infections cause business failures that affect entrepreneurial capabilities (and thus economic growth) long after the pandemic is over. With such costs, it is unsurprising to find that pandemics such as the 1918 pandemic cause economic damage nearly as severe as each of the two world wars.

Economic Freedom and Resilience: New Evidence from the 1918 Pandemic

This essay presents new research that shows the importance of economic freedom—which is taken here as an indicator of institutional quality—in mitigating the damage of pandemics and epidemics.

Summary

Policymakers should consider that

-

the costs of epidemics and pandemics are a function of their pathological features and of the institutional environment in which they occur;

-

economically free countries impose fewer hurdles to entrepreneurs to try new solutions, so they experience a shallower and shorter economic contraction than less economically free countries;

-

once the pandemic fades, business activity can bounce back faster in freer countries; and

-

freer countries perform better on other dimensions of health outcomes.

However, during the COVID-19 pandemic, numerous economists and epidemiologists have proceeded as if the disease’s cost to society is fixed. This is incorrect. The cost of epidemics and pandemics is a function of their pathological features and of the institutional environment in which they occur. Scholars have greatly underrated the role of the latter. When epidemics and pandemics break out, people face tremendous uncertainty (i.e., about the degree of infectiousness of the disease, how to avoid contracting it, how to treat the infected, etc.), and this uncertainty leads to trial and error, which can be quite costly. Entrepreneurs must experiment and take risks to find out how to shift resources that were allocated according to pre-pandemic conditions to purposes that are fitted to pandemic conditions. This reallocation process has costs. Governments can impose parts of these costs through barriers to entrepreneurship, regulatory burdens, trade barriers, and insecure property rights (all of which lessen the profit incentives to try new solutions and to adapt and mitigate).

This essay presents new research that shows the importance of economic freedom—which is taken here as an indicator of institutional quality—in mitigating the damage of pandemics and epidemics. The logic is very simple: economically free countries impose fewer hurdles to entrepreneurs to try new solutions, so they experience a shallower and shorter economic contraction than less economically free countries. Once a pandemic fades, business activity can bounce back faster in freer countries. Moreover, freer countries perform better on other dimensions of health outcomes.

The 1918 Pandemic and Economic Freedom

While there were other pandemics during the 20th century, the 1918 influenza epidemic was the century’s deadliest. It killed at least 50 million people and infected close to half a billion (when the world’s population was roughly a fourth of what it is now). The disease was peculiar in that it disproportionately killed prime-age individuals unlike other influenza outbreaks, which tended to disproportionately kill the very young and the very old. Thus, in addition to the costs from people distancing voluntarily and limiting their activities, there were important reductions in production due to the high mortality rate in the workforce. As a result, the cost of that pandemic has been estimated at 6 percent of gross domestic product (GDP) per capita on average (for a sample of 43 countries), whereas World War I imposed an average cost (for the same sampled countries) of 8 percent of GDP per capita. However, in an article with Jamie Bologna Pavlik, I argue that this cost was heavily determined by the level of economic freedom enjoyed in different countries. There is good reason for holding that economic freedom is a key determinant of resiliency in the face of crises. Economist Christian Bjørnskov assembled a database of 212 macroeconomic crises for 175 countries from 1993 to 2010. His goal was to test whether economic freedom made the contractions that followed these crises shorter and shallower. He found that greater economic freedom was associated with smaller peak-to-trough ratios of GDP (i.e., his measure of the depth of the contraction) and a fewer number of years needed to return to pre-crisis GDP levels. As his results cover various countries, this gives weight to the idea that economic freedom mitigates the costs of crises.

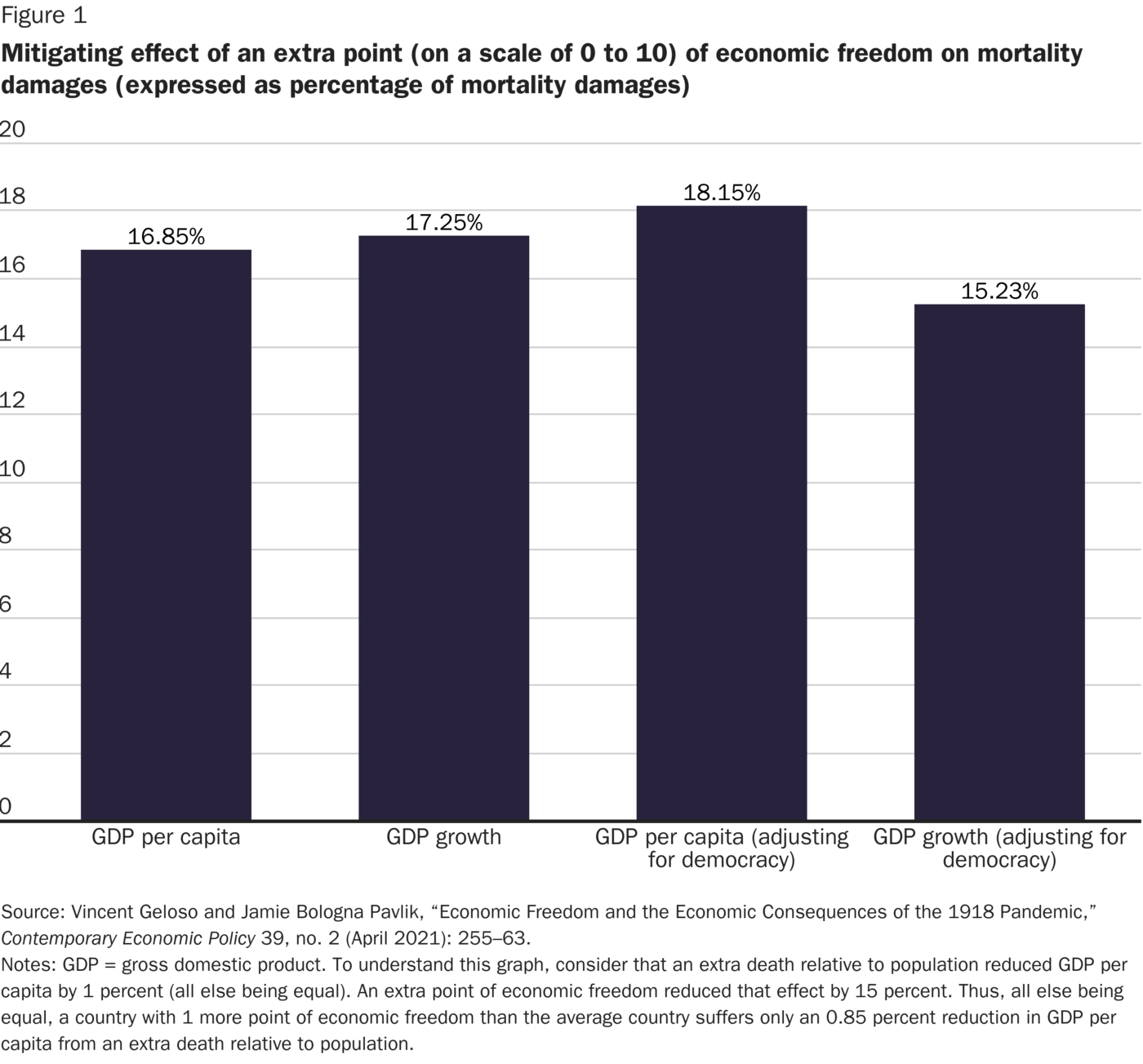

Using a new index of economic liberty that focuses on property rights, trade openness, regulatory burdens, and sound money, Bologna Pavlik and I extended Bjørnskov’s logic to the 1918 pandemic. We looked at economic growth data between 1901 and 1929 and used the mortality rate from the pandemic as a measure of the size of the exogenous shock it imposed. The greater the mortality rate, the greater the contraction. We also accounted for the effect of World War I and attempted to control for country-fixed effects and the role of democracy. As Figure 1 shows, our economic specifications showed that an extra point of economic freedom (on a scale of 0 to 10) mitigated between 15 percent and 18 percent of the economic damage (either on income levels or on economic growth rates) of an additional death relative to the population.

We then broke down the effects into the subcomponents of the economic liberty index. Property rights and regulatory burdens yielded the most consistent effects. The security of property rights speaks to the ability of entrepreneurs to appropriate the gains of their efforts and risk-taking, while regulatory burdens speak to the costs of undertaking these efforts. In other words, economically free countries made it more rewarding to experiment with solutions to adapt to the pandemic, which in turn eased the suffering the pandemic induced.

Featured Video

Generalizability of Results

There are good reasons to believe that our results are conservative. Richer and quite economically free countries make up the index of economic freedom that we used. There was no exceptionally unfree country in our samples. Thus, our results are based on very small variations of economic freedom. It is likely that including less free countries in our sample would have reinforced our findings by allowing us to see the effects of being dramatically less free.

Another reason for believing that the result is robust is that the finding appears generalizable for more pandemics than the 1918 one. Alongside Rosolino Candela, I collected data about excess mortality based on crude mortality rates in all the major pandemics since 1850 (i.e., 1857–1858, 1889–1890, 1918–1920, 1957–1959, 1968–1970, and 2009–2010). We used the same index of economic freedom to see if economic freedom minimized the damages of each pandemic. We found that our crude measure—for lack of alternatives—of mortality did predict consistent and significant contractions in economic activity. However, we also found that economic freedom had a positive effect on economic growth during pandemics.

Protective Effects of Economic Growth

Certain diseases, such as those associated with epidemics and pandemics, can be mitigated effectively through coercive measures applied by governments to limit contagion. These diseases can be labeled “diseases of commerce” because they spread mainly because of exchanges between people. Other diseases, such as typhoid fever, cardiovascular diseases, and diarrhea are more sensitive to income levels and can be termed “diseases of poverty.”

While several liberal Western democracies, such as Australia and New Zealand, deployed fairly draconian tactics to fight COVID-19, it’s fair to say that less economically free countries have greater ability to deploy extreme coercive measures to fight contagion. Economically liberal countries are arguably more vulnerable to diseases of commerce.

Featured Report

Economic Freedom of the World

Economic Freedom of the World seeks to measure the consistency of the institutions and policies of various countries with voluntary exchange and the other dimensions of economic freedom. The report is co‐published by the Cato Institute, the Fraser Institute in Canada and more than 70 think tanks around the world.

Even so, “state capacity” to impose extreme coercive measures comes with a serious institutional trade-off. Governments with such capabilities can also easily disregard property rights. Their greater coercive capacity may allow for more aggressive pandemic mitigation, but this ability comes with lower levels of economic freedom and thus slower economic growth. In other words, freer countries have fewer coercive tools to deal with pandemics, but the economic growth they enjoy allows them to combat other diseases better. Moreover, diseases of poverty have accounted for the bulk of human deaths historically, and given its strong association with economic growth, economic freedom reduces this source of mortality dramatically.

In an article with Kelly Hyde and Ilia Murtazashvili, I documented this trade-off using two key diseases during the 19th century and the first half of the 20th century—smallpox, which is a disease of commerce, and typhoid fever, which is a disease of poverty. We found that economically freer nations have no statistically significant advantage in dealing with smallpox. However, these nations had a significant and considerable advantage than less free nations in terms of reducing typhoid fever. Given that the deaths from typhoid fever were many times more numerous than those from smallpox, economic freedom was essentially combating the most damaging disease.

Conclusion

These findings point to the crucial importance of economic freedom to resiliency. A significant test of any economic system is its ability to adjust to unexpected exogenous shocks, such as natural disasters and pandemics. As F. A. Hayek said, an economic system’s superiority relative to others is determined by whether it “leaves room for the unforeseeable and unpredictable.” This ability is what scholars like Mark Pennington and Peter Boettke call “robust political economy.” Economically free countries, by securing property rights, allow entrepreneurs to profit from their decisions. This ability to appropriate gains from exchange and innovation creates powerful incentives to learn and rapidly adjust. Limiting regulatory burdens also makes entrepreneurial activity easier to undertake. Combined, these forces make it easier to withstand shocks.

This is the underappreciated point of the COVID-19 pandemic. A pandemic is rife with uncertainty, and adjustment requires the discovery of new information. This discovery is fastest in systems that decentralize decision-making by allowing entrepreneurs, workers, medical personnel, and consumers to experiment with solutions. Their solutions, when observed by others, can then be further improved. The pace and potency of this discovery process depends on the incentives offered to these individuals. Such incentives, as documented in the cases of earlier pandemics, appear to be stronger in economically free countries.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.