Introduction

In the wake of the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, the United States launched an international war on terrorism defined by military intervention, nation building, and efforts to reshape the politics of the Middle East. As of 2017, however, it has become clear that the American strategy has not delivered the intended results.

After 15 years of considerable strategic consistency during the presidencies of George Bush and Barack Obama, Donald Trump now takes the reins, having made a more aggressive approach to ISIS a central plank first of his campaign and, potentially, of his presidency. Noting that America faces a "far greater threat than the people of our country understand," he has vowed to "bomb the sh— out of ISIS"1 and promised to defeat "Radical Islamic Terrorism, just as we have defeated every threat we have faced in every age before."2

At the same time, however, Trump has also broken sharply from Republican orthodoxy on Iraq and Afghanistan. He refers to "our current strategy of nation-building" as a "proven failure." Additionally, he has downplayed the role of democracy promotion, suggesting, for example, that the Obama administration "should never have attempted to build a democracy in Libya."3

Whatever President Trump decides to do, a dispassionate evaluation of the War on Terror to date should inform his policies.

In this policy analysis, we argue that the War on Terror has been a failure. This failure has two fundamental — and related — sources. The first is the inflated assessment of the terrorist threat facing the United States, which led to an expansive counterterrorism campaign focused on a series of actions that have very little to do with protecting Americans from terrorist attacks. The second source of failure is the adoption of an aggressive strategy of military intervention. This is due in large part to the faulty assessment of the terrorism challenge. But it also stems from the widespread belief among Washington, D.C., elites in the indispensable nature of American power and the utility of military force in international politics. Together, these factors have produced an American strategy that is both ineffective and counterproductive.

The inescapable conclusion of our analysis is that the staggering costs of the War on Terror have far outweighed the benefits. A recent study by Neta Crawford at Brown University puts the cost of the War on Terror (both money spent to date and required for future veterans’ benefits) at roughly $5 trillion — a truly astonishing number.4 Even if one believes American efforts have made the nation marginally safer, the United States could have achieved far greater improvements in safety and security at far less cost through other means. It is not hyperbole to say that the United States could have spent its money on almost any federal program aimed at saving lives and produced a vastly greater return on investment.5

A careful reading of the lessons from the past 15 years indicates that the United States should abandon the existing strategy in the Middle East for three reasons. First, military intervention and nation building efforts, even at current "light footprint" levels, cause more problems than they solve, including spawning more anti-American sentiment and creating, rather than diminishing, the conditions that lead to terrorism.6 Second, in contrast to the dire picture painted by many observers, including President Trump, the terrorism threat is too small to justify either the existing strategy or more military intervention. Finally, given the first two arguments, the costs of a forward-deployed strategy to fight terrorism are simply too high.7

Our analysis proceeds in four parts. In the first section we review the main objectives of the War on Terror and the key components of U.S. strategy designed to achieve them.8 In section two we document the failure of U.S. policies to achieve the goals articulated by both Presidents Bush and Obama. In section three we explain why War on Terror policies may have yielded the results they did, producing a set of important lessons learned to inform future policy. We conclude by arguing that the United States should ramp down its War on Terror, and we outline the principles of a "step back" strategy regarding ISIS and Islamist-inspired terrorism.

U.S. Objectives and Strategy in the War on Terror

In the 2003 National Strategy to Combat Terrorism, the Bush administration declared its central objectives in the War on Terror: "The intent of our national strategy is to stop terrorist attacks against the United States, its citizens, its interests, and our friends and allies around the world and ultimately, to create an international environment inhospitable to terrorists and all those who support them."9

As many observers have noted, 9/11 prompted the Bush administration to radically overhaul the American approach to confronting terrorism. Prior to the attacks of 9/11, the U.S. government viewed domestic terrorism as a matter for law enforcement and international terrorism as a distant threat. Accordingly, American foreign policy focused very little on the issue of terrorism. When the United States did occasionally conduct foreign policy to retaliate for terrorism, such as the attacks on the Berlin disco or the U.S. embassies in Africa, the means were quite limited, as with the 1986 bombing of Libyan command-and-control sites or the 1998 cruise missile strikes in Afghanistan and Sudan. After the attacks of 9/11, terrorism took center stage in national security policy and the limited-response approach gave way to a far more aggressive and expansive strategy that the Bush administration in 2003 called the "4-D" strategy.10

The 4-D strategy to prevent terrorist attacks on the United States comprised four primary missions: to defeat terrorist organizations with global reach, to deny such organizations sanctuaries from which to operate and launch attacks, to diminish the conditions that give rise to the use of terrorism, and to defend the United States through "proactive" defense of the homeland.

The logic of the Bush strategy was straightforward. In order to prevent attacks against the United States in the short term, al Qaeda and similar terrorist organizations had to be disrupted and their capabilities degraded. In the medium term, aggressive action against terrorist groups would help deter other groups from attacking and make potential state sponsors of terrorism think twice. In the longer term, security would best be achieved by eradicating the underlying conditions that the Bush administration (and later the Obama administration) believed had given rise to terrorism in the first place. Among these conditions were ethnic and religious conflict, corruption, poverty and lack of economic opportunity, and social and political oppression.11

Military Intervention

Since 2001 the most important component of the international War on Terror has been direct military intervention. This decision to confront terrorism with military force, rather than through the more traditional law enforcement framework, has significantly shaped the War on Terror and helped determine its outcomes.

At this point it is useful to be clear about terminology. The Department of Defense defines military intervention as "The deliberate act of a nation or a group of nations to introduce its military forces into the course of an existing controversy."12 We further differentiate between direct and indirect military intervention. Direct military intervention involves sending American troops to fight, occupy, or defend territory in other nations or conducting air strikes (whether via drones or manned airplanes) or missile strikes. Examples of direct military intervention include the invasion and subsequent occupation of Afghanistan and Iraq, the far-flung American drone campaign, U.S. military support for Iraq in its efforts to retake territory from the Islamic State, and U.S. Special Forces supporting local counterterrorism efforts in Tunisia, Somalia, Mali, and Nigeria.

Indirect military intervention, on the other hand, involves providing various kinds of support (intelligence, military equipment, advising, money, and training) to facilitate the use of military force by a third party. The effort to arm and train Syrian rebel groups to fight the Islamic State is one example of indirect military intervention. U.S. intelligence, arms sales, and logistical support for the Saudi intervention in Yemen is another.

Both forms of military intervention, in turn, are distinct from the wide variety of nonmilitary tools available to the United States. Those tools can be noninterventionist, as in the case of economic sanctions, diplomacy and negotiations, and freezing terrorist groups’ financial assets. Others, however, such as nation building and democracy promotion, are certainly forms of intervention in the sense that they either require American military involvement (such as in Afghanistan and Iraq) or they feature a steady dose of American political pressure and financial assistance aimed at shaping outcomes in another nation.

Although it has taken several forms, the central purposes of American military intervention — direct and indirect — have remained consistent since 2001. First and most simply, of course, the goal of military intervention has been to kill terrorists, destroy their organizations, and eliminate their ability to conduct terrorist operations. A critical foundation of this strategy was the belief that the United States could no longer wait until the threat was fully formed. Instead, the United States needed to begin preemptively striking with military force. Beginning with the 2002 National Security Strategy, the Bush administration put forth a doctrine of preventive action against terror threats, even if those threats were not yet imminent.13 As Bob Woodward reported, "Many in the Bush administration felt President Clinton’s prior responses to terror attacks had been weak and inadvertently emboldened terrorists. There would, therefore, be no Clintonian ‘reflexive pullback’ this time."14 Instead, the Bush administration set the United States on an offensive path, seeking to destroy and defeat terror groups overseas so, as President Bush said, "we do not have to face them in the United States."15

Second, U.S. officials have viewed the use of military force as a deterrent against future terrorism. Beyond the effort to destroy al Qaeda, the invasion of Afghanistan also served as punishment for the Taliban for harboring the terrorist group and a warning to other state sponsors of terrorism. Similarly, despite the fact that Iraq was not an al Qaeda sponsor, the Bush administration clearly viewed the invasion of Iraq as an important opportunity to show resolve in the "central front in the war on terror."16

Third, officials have viewed military intervention as a critical tool to prop up weak governments and to prevent terrorist groups from taking territory and staking out safe harbors in weak states. The United States and its European allies have sought to help the newly formed National Unity Government in Libya by conducting air strikes against ISIS, for example. And in Yemen, the United States has conducted drone strikes against al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula since 2010 but more recently has provided military and intelligence assistance to Saudi Arabia as it intervenes in support of the embattled Yemeni government.17

It is important to note that the election of Barack Obama provoked little change at the strategic level. In addition to the continued fight against the Taliban and other jihadist groups in Afghanistan and the major efforts against ISIS in Syria and Iraq, the United States under Obama conducted drone strikes, air strikes, and Special Forces operations in Pakistan, Syria, Libya, Somalia, and Yemen.18 It is true that Obama pulled U.S. troops out of Iraq, a move that would later be criticized for spurring the rise of ISIS. But this was not inconsistent with the Bush approach. In the Status of Forces agreement that he signed with Iraq in 2008, Bush committed to withdraw all U.S. troops by 2011.

Remaking the Middle East

The United States has also invested heavily in efforts to remake and reshape the Middle East in pursuit of longer-run and more fundamental solutions to the root causes of terrorism. Both the Bush and Obama administrations argued that terrorism springs from unhealthy political and economic systems and that terrorist groups will flourish where states are too weak to exert effective control over their own territory.19 The result has been a long-term campaign that started with regime change to depose supporters of terrorism, evolved into democracy promotion and nation building to encourage the development of future allies and well-behaved nations, and finally has left the United States with the challenge of propping up weak and unstable governments.

Buoyed by perceived early success in promoting democracy in Afghanistan, President Bush frequently articulated his conviction that America had a responsibility to liberate people.20 In 2003 President Bush announced what he called a "forward strategy for freedom in the Middle East." After the first elections in Afghanistan and Iraq, President Bush intensified his calls for democracy in the Middle East, promoting it as a cornerstone of the War on Terror.21 Bush believed democracy could provide the transformation necessary to diminish the underlying conditions of terrorism and solve the problem of Islamic extremism.22 National strategy documents promulgated by both the Bush and Obama administrations have identified the promotion of democracy as the long-term solution in the fight against terror and the best way to achieve enduring security for America.23

Beyond regime change and democratization, the United States has also used nation building as a key tool for remaking the region. After disbanding them in 2003, for example, the United States helped rebuild and retrain the Iraqi security forces, although clearly with mixed results.24 Thanks to U.S. efforts, the Afghan security forces now number 350,000.25 As of late 2015, the United States has spent approximately $90 billion training and equipping the Afghan and Iraqi armies and police.26 The United States also has spent $104 billion to help Afghanistan rebuild since 2001 and $60 billion dollars to rebuild Iraq since 2003.27 To handle much of the implementation for these policies, the government established provincial reconstruction teams comprised of military and civilians from the Department of State, the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), and the Department of Agriculture. Those teams infused money and expertise into both countries, with projects ranging in scale from single, manually operated water pumps to hydroelectric dams. Additionally, the teams conducted training for Afghan and Iraqi government officials.

Mission Not Accomplished: Assessing the War on Terror

By any measure, the war on terrorism has been far-reaching. But despite the scale of this campaign the question remains: What does the United States have to show for all this effort?

Measuring the effectiveness of the War on Terror is a tricky business; citizens and experts alike can reasonably argue about the most important determinants of success and failure. Assessments may vary based on the level of analysis being conducted and which outcomes are emphasized (e.g., lives lost, terrorists killed, the destruction of specific terrorist groups, etc.). Regardless of the definition used, however, every assessment should answer the critical question of whether the United States has reduced the terror threat since 9/11. Any assessment should also address whether or not the government has met the goals it set for itself and has pursued consistently for the past 15 years.28

Even by a conservative accounting, the War on Terror has been a failure. First, although the United States has not suffered another major terrorist attack since 9/11, there is no proof that intervention abroad had anything to do with that, despite killing thousands of terrorist group members. Nor has the War on Terror made Americans appreciably safer (nor made them feel safer) than they were before 9/11, in part because Americans were already exceptionally safe and in part because, again, offensive counterterrorism efforts have had little or no connection to the rate of terrorism in the U.S. homeland.29 In fact, the most likely case is that foreign intervention has made Americans somewhat less safe. Second, the United States has not destroyed or defeated al Qaeda, the Islamic State, or any other terror groups of global reach, regardless of how well or poorly the description applies to groups comprised of a few hundred or a few thousand people. Nor, finally, has the United States made a dent in diminishing the underlying conditions supposed to give rise to terrorism. Instead, more Americans have died from terror attacks and there have been more Islamist-inspired attacks within the homeland since 9/11 compared to the same period before, while the number of Islamist-inspired terror groups has proliferated since the War on Terror began. Moreover, the number of terror attacks worldwide has skyrocketed, indicating that the conditions driving the use of terrorism are very likely worse than ever.

Figure 1: Islamist versus Non-Islamist Terror Events in the United States

Source: Global Terrorism Database at the University of Maryland.

In the next several sections we present more detailed discussion of American progress toward each of these key objectives.

Objective #1: Preventing Terrorist Attacks in the United States

The United States has fortunately not suffered a second major attack on its soil since September 11, 2001. Historically speaking, a major attack is an outlier. Outside of 9/11, terrorists have killed very few Americans in the homeland. Between 1986 and 2001 there were four Islamist-inspired terrorist attacks in the United States, which killed 10 Americans.30 Since the 9/11 attacks there have been eight attacks, killing 88.31As Figure 1 shows, the level of Islamist-inspired attacks has never come close to the rates of non-Islamist terrorism in the United States in the mid 1970s.

These data reflect a modest increase with respect to the rate and lethality of Islamist-inspired terrorism since 9/11. But post-9/11 Islamist-inspired terrorism also remains almost invisible when viewed in relation to the more than 230,000 people murdered by fellow Americans during the same period.32 Islamist-inspired terrorists took the lives of less than one-tenth of 1 percent of American murder victims over the last 15 years.33 Americans who are not terrorists carry out nearly all murders in America.

What is unclear from the figures alone, however, is what role the international War on Terror has played in shaping that trend.

Broadly speaking, the data are consistent with three possible interpretations. The first is that the War on Terror has had little or no effect on Islamist-inspired terrorism against Americans. The second possibility is that the numbers would look far worse in the absence of the War on Terror. The third possibility is that the War on Terror has, in fact, set the conditions for the slight uptick in anti-American terrorism observed since 9/11.

The "no effect" possibility comes in two versions. The first is that the 9/11 attacks, although spectacular, did not provide al Qaeda (or any other group) with sufficient strategic justification to repeat them or to work very hard to conduct other, smaller attacks against the United States.34 To date, for example, there is no evidence that any group has plotted or attempted another attack against the U.S. homeland on the scale of 9/11. Although the attacks certainly helped establish the al Qaeda "brand" globally, the attacks failed to convince the United States to leave the Middle East as al Qaeda had hoped.35 Given this, it may be that al Qaeda concluded its resources would produce a better return if applied elsewhere. Meanwhile, regional al Qaeda affiliates are even more devoted to local and regional priorities, as is the Islamic State, which has its hands full fighting on multiple fronts to seize and defend territory in Syria, Iraq, and elsewhere.

The second possibility is that improved homeland defense, as opposed to international action, has helped prevent additional attacks. The United States responded to the 9/11 attacks by investing heavily in homeland security, upgrading airline security, hardening ports of entry and major government buildings, and improving intelligence and law enforcement coordination.36 Proponents of this argument also point to as many as 93 plots against the United States that have been foiled by American intelligence and homeland security efforts.37 Whereas al Qaeda had the element of surprise working for them in a significant way in 2001, the same was no longer true afterwards.

But even here one has to question whether the United States has been lucky, as opposed to good. Many scholars have offered sharp criticisms of the American homeland security project, suggesting that, despite some improvements, the United States remains essentially as vulnerable as before to terrorists.38 And no matter how many critical nodes the United States attempts to protect, there are a nearly infinite number of potential ways to inflict significant numbers of casualties in such a large and open society. As former Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) Director George Tenet wondered in his autobiography, "it would be easy for al-Qaeda or another terrorist group to send suicide bombers to cause chaos in a half-dozen American shopping malls on any given day. Why haven’t they?"39

In their exhaustive investigation into post-9/11 terrorist plots, John Mueller and Mark Stewart point out that, despite the fact that 173 million foreigners enter the United States legally each year, al Qaeda has conducted exactly zero successful attacks since 9/11. To those who might argue that the United States has, in fact, disrupted many undisclosed plots, Mueller and Stewart argue: "if undisclosed plotters have been so able and so determined to commit violence, and if there are so many of them, why have they committed so little of it before being waylaid? And why were there so few plots in the months and years following 9/11, before enhanced security measures could be effectively deployed?"40 Mueller and Stewart also cite former CIA analyst and terrorism expert Marc Sageman, who told them, "As a member of the intelligence community, who kept abreast of all the plots in the U.S., I have not seen any significant terrorist plots that have been disrupted and not disclosed. On the contrary, the government goes out of its way to take credit for non-plots, such as their sting operations."41

Contrary to concerns that al Qaeda and ISIS remain a major threat to the United States, historically major terrorist attacks outside of a war zone are quite rare. Before and since 9/11, the most catastrophic terror attacks have occurred almost exclusively in failing states or states at war. Prior to September 11, 2001, the most catastrophic global terror attack caused just over a third of the fatalities of 9/11. That attack occurred in Rwanda during the genocide of 1994, when 1,180 Tutsis seeking refuge in a church were targeted.42 The next most severe terror attack was only a sixth of the size, and it occurred in Iran during the Islamic revolution in 1979.43 Since 9/11, the most catastrophic attacks, ranging from 400 to 1,700 fatalities, have occurred in Iraq, Syria, Nepal, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo.44

The second interpretation of the data, touted by both the Bush and Obama administrations, is that the international war on terrorism — not simply improved homeland security efforts — has prevented acts of terrorism on U.S. soil. The argument here was twofold. First, by killing terrorists and disrupting or destroying their organizations, the United States made it impossible for those groups to strike the United States. Second, by demonstrating American resolve, the War on Terror served as a deterrent since terrorist groups realized the futility of conducting attacks against the United States.

History has revealed serious gaps in the strategic logic of the War on Terror. First, despite unprecedented counterterrorism efforts across the Middle East and Northern Africa, the United States has clearly not managed to eliminate the terrorists or destroy their organizations. The initial military action in Afghanistan severely disrupted al Qaeda’s ability to operate there, but as the War on Terror expanded to Iraq and beyond, the limits of conventional warfare for counterterrorism became evident. Militaries are very good at destroying large groups of buildings and people and for taking and holding territory, but they are not designed to eradicate groups of loosely connected individuals who may, at any moment, melt into the civilian population. Even with drones and Special Forces, the ability of the United States to dismantle al Qaeda and its affiliates has proven quite limited. Moreover, the chaos sown by the invasions of Iraq and Afghanistan inadvertently helped spawn the birth and rapid growth of new jihadist groups, including the Islamic State.

Second, the argument that U.S. international efforts have had a strong deterrent effect is highly suspect. It is difficult to imagine the United States having provided a more powerful statement of resolve than the invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq, complemented by a steady stream of drone strikes across at least seven different nations. The lesson to future terrorists should have been quite clear: if you attack the United States there will be nowhere to hide; the American military will kill you and, potentially, topple your country’s political regime. Nonetheless, in the wake of the concerted U.S. campaign, the jihadists appear undaunted, with the Islamic state emerging thanks in part to the chaos in Iraq. Today, the Islamic State’s rhetoric and actions align to make clear that the American (and allied) military presence is a far more powerful recruitment tool than it is a deterrent. During the 2015 attacks in Paris, for example, one of the attackers was heard blaming French President Hollande for intervening in Syria.45

Finally, the third possible interpretation of the data is that the War on Terror inadvertently fueled more anti-American terrorism. The argument here is that, had the United States conducted a limited intervention to disrupt al Qaeda, withdrawn quickly from Afghanistan, and not invaded Iraq, many, if not most, of the post-9/11 attacks would not have taken place. Without an ongoing American presence and an active military campaign helping to further radicalize and motivate potential jihadists, observers point out, it is reasonable to expect that there would have been far less incentive for al Qaeda and related groups to attack the United States. Further, had the United States not invaded Iraq, it is doubtful that ISIS would even exist.46

Table 1: Number of Islamist-inspired Terror Groups and Fighters

Source: Department of State Country Reports on Terrorism 2000 through 2015, Stanford University’s Mapping Militant Organizations Project.

This is not to argue that al Qaeda and ISIS would not still have some desire to strike at American targets even if the United States were not active in the Middle East, but as noted above, it is clear that the Islamic State, at least, is using the American presence in the Middle East as a justification for anti-American terrorism. If nothing else, continued American military action in the Middle East ensures that ISIS will remain highly visible in the news and in the minds of Americans, providing potential lone wolves in the United States inspiration to carry out future attacks.

Objective #2: Destroy and Defeat al Qaeda and Terror Groups with Global Reach

Although the level of terrorism aimed at Americans has increased only slightly since 2001, the number of Islamist-inspired terrorist groups and terror attacks in the Middle East and elsewhere has skyrocketed.47 Analysts might rightly question how global the reach of some of these new organizations truly is, but the government’s rhetoric over time suggests that we should include any terrorist group capable of launching or even inspiring attacks outside their own home nation. By this measure, the United States has failed to achieve its stated objective. Although American military intervention in Afghanistan and Pakistan effectively put the central al Qaeda organization out of business for some time, al Qaeda affiliates have proliferated around the world, one of which — al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula — is routinely identified as the most dangerous group operating today.48 Most troubling on this score, as noted, is that the war in Iraq inadvertently helped pave the way for the emergence of the Islamic State.

The growth of the jihadist terrorist enterprise since 2001 has been stunning. When the War on Terror began, there were roughly 32,200 fighters comprising 13 Islamist-inspired terror organizations. By 2015, as Table 1 shows, the estimate had ballooned to more than 100,000 fighters spread across 44 Islamist-inspired terror groups.49

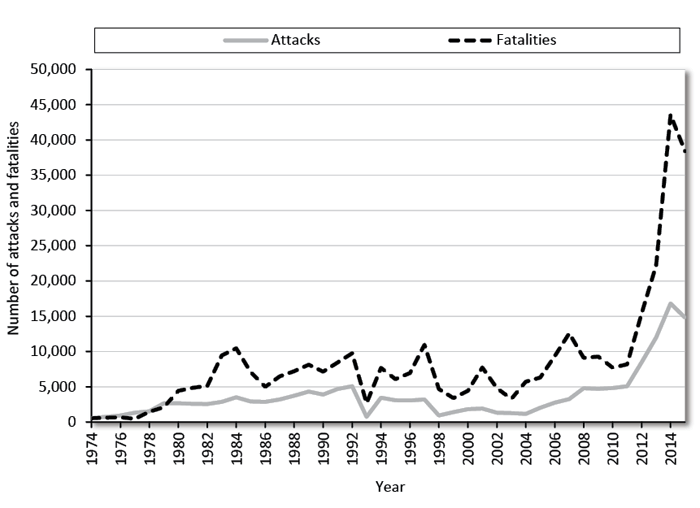

This growth has led to an even more explosive rise in violence — most of which has occurred in the Middle East and Africa. As Figure 2 indicates, there were 1,880 terror attacks worldwide in 2001 when the U.S. began its War on Terror. In 2015 the number was 14,806. Fatalities caused by terror attacks have also increased. As the below figure indicates, fatalities worldwide have risen to unprecedented levels. In 2015, 38,422 people were killed by terrorism — a staggering 397 percent increase from 2001.

These figures strongly suggest that the War on Terror has not only failed to defeat al Qaeda and other major terrorist groups, but has also failed to contain the growth of Islamist-inspired terrorism more generally. The argument that things might have been worse in the absence of such an aggressive American effort rings hollow, especially given the manner in which the war in Iraq produced the chaos that gave ISIS room to operate and provided additional motivation and justification for anti-Western attacks. Further, a closer analysis of the chronology of the War on Terror provides support for the conclusion that the United States has made things worse rather than better. As Figure 3 shows, terror attacks rarely occurred before 9/11 in the seven countries in which the U.S. executed military operations as part of its War on Terror.

Figure 2: Worldwide Terror — Attacks and Fatalities

Source: Global Terrorism Database at the University of Maryland.

To investigate the impact of U.S. military intervention, we compared the terror rates between War on Terror states, other Muslim majority countries, the United States, and the global average. Additionally, we created regression models to examine the significance, if any, of U.S. military strikes when controlling for other variables often used in the study of terrorism such as a state’s GDP per capita, economic growth rate, social fractionalization, polity, and education levels (see Appendix 1).

As Table 2 reveals, the number of terror attacks rose an astonishing 1,900 percent in the seven countries that the United States either invaded or conducted air strikes in, while other Muslim majority states saw a much more modest 42 percent increase. The regression models also found that countries where the United States conducted air or drone strikes saw a dramatic increase in terror attacks compared to countries where the United States did not conduct strikes.50 Even more startling, the models showed the greatest effect when comparing drone strikes conducted in year one with the number of terror attacks carried out two years later, a finding consistent with the theory that U.S. strikes have a catalyzing effect on terror groups. In short, contrary to the intentions of the U.S. government, as the War on Terror has expanded, it has led to greater levels of terrorism.

Figure 3:Terror Attacks Where the U.S. Fought the War on Terror, 1987–2015

Source: Global Terrorism Database at the University of Maryland

Table 2: Terrorism Before and During the War on Terror: Average Number of Terror Attacks per Country, per Year

Notes:

"Before 9/11" captures all terror attacks from 1987-2000 (14 years).

"After 9/11" captures all terror attacks from 2002-2015 (14 years).

"Muslim Majority" includes all Muslim majority states except the seven War on Terror states. The list comes from the University of Michigan’s Center for the Education of Women http://www.cew.umich.edu/muslim_majority. The list includes four entries that are not in the Global Terrorism Database. Three are not countries (Mayotte, Palestine, and the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus) and one is not in the database (Oman); no explanation could be found for Oman’s exclusion.

"Global average" includes all states listed in the Global Terrorism Database, except for the seven War on Terror states — 199 total.

Objective #3: Diminishing the Underlying Conditions that Cause Terrorism

Neither the Bush nor the Obama administration imagined the War on Terror would be won quickly. Both acknowledged that changing the underlying context of instability and political conflict in the Middle East would take time. Unfortunately, no evidence exists to suggest that there is a single set of conditions which leads to terrorism, nor any evidence to suggest that terrorism will disappear once those conditions have changed. But even if we accept the argument, there has been little sign of progress toward diminishing the underlying conditions that facilitate terrorism, at least as defined by the U.S. government.

From the perspective of U.S. strategy to date, diminishing the underlying conditions of terrorism includes both material and intangible aspects. The Bush administration’s 2003 strategy for combating terrorism set forth two objectives in this area: "partner with the international community to strengthen weak states and prevent the (re)emergence of terrorism . . . [and] win the war of ideas."51 As to the former, subgoals include resolving regional disputes, fostering development, and bringing about market-based economies and good governance so that states can look after their people and control their borders.

Winning the war of ideas involves assuring Muslims that American values are congruent with Islam and supporting moderate and modern Muslim governments. The Bush 2003 strategy document further states that solving the Israeli-Palestinian conflict is "a critical component to winning the war of ideas."52 The Obama administration’s strategy contains many similar goals while differing in language: counter the ideology, diminish the drivers of violence, and break the cycle of state failure.53

Data show that the United States has failed to diminish the conditions that the government has argued produce terrorism.54 Afghanistan and Iraq have become even more corrupt since the United States began pouring in resources. In Afghanistan and Iraq’s first year in the Transparency International’s Corruption Perception Index (2003 and 2005), they occupied the 26th and 15th percentile, respectively. By 2016, they had plummeted to the fourth and sixth percentile. The average corruption percentile ranking for the seven countries in which the U.S. has conducted military operations has deteriorated by 14 percentage points.55 Additionally, six of the seven countries remain mired in Freedom House’s worst category — not free — although political rights and civil liberties have improved negligibly.56 Finally, in terms of weak and failed states, the State Fragility Index’s characterization of Afghanistan and Iraq remains unchanged. Before the War on Terror began, Afghanistan was in the worst category (extreme fragility) and Iraq was in the second worst (high), and they remain there today. Of the other five countries, three have worsened and two remain unchanged.57

Explaining Failure

The failure of the War on Terror has two fundamental — and related — sources. The first is the inflated assessment of the terrorist threat facing the United States, which led to the decision to commit to an expansive counterterrorism campaign focused on a series of actions that have very little to do with protecting Americans from terrorist attacks. The second source of failure is the adoption of an aggressive strategy of military intervention, which was largely driven by the failure to define the terrorism challenge accurately. But it also stems from the widespread belief among Washington, D.C., elites in the indispensable nature of American power and the utility of military force in international politics. Together, these factors have promoted an American strategy that is both ineffective and counterproductive.

Error #1: America’s Inflated Assessment of the Terrorist Threat

The September 11 attacks were devastating, and given America’s lack of experience with such events, fear, confusion, and overreaction were understandable responses in the short run.58 But with the benefit of hindsight it is clear that the terrorist threat to the United States is, in fact, much smaller than originally imagined.59 Unfortunately, rather than correct the initial threat assessment, political leaders from both parties (and like-minded think tanks) have continued to portray terrorism as a very large, even existential, threat to the United States.60

This inflated view of the terrorist threat led directly to the excessive size, scope and ambition of the War on Terror. Rather than simply looking to punish al Qaeda for 9/11, the Bush administration quickly decided that the United States must not only destroy al Qaeda but all other terrorist groups with global reach and then eliminate the underlying conditions that gave rise to them.

Declaring war on terrorism was an exercise in futility. Terrorism is not a disease that can be eradicated through vaccination, but a strategy that all kinds of people have chosen to use for all kinds of reasons in all sorts of places and situations. History shows that terrorism has been a hallmark of wealthy states as well as poor ones, of secular as well as religious groups, and of conservative as well as insurgent and progressive causes.61 The call to eliminate terrorism may play well politically, but it will never be a serious policy proposal no matter how many trillions of dollars the United States spends on it.

This is not to deny that al Qaeda and the Islamic State pose a threat to Americans. They do. The question here, however, is whether the American response to 9/11 and the War on Terror — in particular the strategy of military intervention — has been an effective one. By defining the threat in inflated, even existential, terms, the United States has expanded the War on Terror far beyond the necessary boundaries, creating new problems while failing to resolve the original ones, all at a cost that is far too high.

Error #2: Flawed Counterterrorism Strategy

The American approach to fighting terrorism in the Middle East suffers from three related flaws.

First, American intervention has aimed at the wrong target. Political grievances and competition for power in the Middle East, not a radical Islamist hatred of the West, are the primary sources of conflict both in the Middle East and between Islamist groups and the West. Unfortunately, since the beginning of the War on Terror, too many American officials have believed that the motivation for al Qaeda and ISIS terrorist attacks against the United States is primarily an anti-American ideology, hatred of our freedoms, or the desire to destroy the United States.62

Believing that this hatred of the United States is the "on button" for terrorism, America’s short-term strategy has centered on killing those terrorists, while the vision in the longer-term is a battle for the hearts and minds of the Muslim world in order to eliminate negative beliefs about the United States. This long-run strategy involves not only reshaping the narrative about Islam and the West but also reshaping Middle Eastern governments in the Western image.

Tragically, this approach has the United States working the wrong problem entirely. The motivation for al Qaeda, its various affiliates, and ISIS are local and regional. They seek, along with many others, to control the political systems of the Middle East. It is true that both ISIS and al Qaeda have discussed the importance of striking the "far enemy" (the United States) as a strategy for recruitment and to weaken the "near enemy" (local Arab governments). But as Osama bin Laden and other jihadist leaders have made clear, the United States is implicated in their plans not because the jihadists hate its freedoms or because the destruction of the Western way of life is their goal, but because American foreign policy blocks their path to power in the Middle East.63

The second flaw in the American strategy is the reliance on military means. Misled by a misdiagnosis of the underlying problem, the United States has pursued an interventionist strategy focused overwhelmingly on destroying terrorist organizations and killing individual terrorists. Research has shown that this is rarely the path toward a permanent solution to terrorist groups.64 Over the past 15 years American efforts have produced short-term effects as jihadists scatter in the face of drone strikes and American intervention. In the longer run, however, military force is the wrong tool for the mission. As the former commander of U.S. forces in Afghanistan, General Stanley McChrystal, has famously noted, the United States can’t "kill its way out" of the war against terror groups such as ISIS and al Qaeda.65

American intervention has likely made things worse. The invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq, along with the toppling of Muammar el-Qaddafi in Libya and the U.S.-supported war in Yemen, have created chaos, allowing insurgent and terrorist groups more room to operate. Drone strikes, targeted killings, and the enduring American presence in these places have also generated more anger and resentment toward the United States, boosting jihadist propaganda and recruiting efforts.66 Nor is the resentment limited to the jihadists themselves. Public attitudes in many Muslim-majority countries toward the United States cratered in the wake of the 2003 invasion of Iraq and have remained dismal since then.67

In the absence of continued U.S. intervention, al Qaeda and ISIS would likely have had less motivation to carry out such attacks — at least in the United States. Faisal Shahzad, who attempted to set off a bomb in New York’s Times Square in 2010, illustrates the dynamic. In court, Shahzad explained his actions, "I want to plead guilty 100 times because unless the United States pulls out of Afghanistan and Iraq, until they stop drone strikes in Somalia, Pakistan and Yemen and stop attacking Muslim lands, we will attack the United States and be out to get them."68 Shahzad’s words echo the repeated statements of terror leaders such as Osama bin Laden and Ayman al-Zawahiri.69 In various strategy documents they highlight the centrality of America (and Israel) to their recruiting success.

The U.S. government seems to understand this, at least in theory. As early as 2004, a Defense Science Board report noted that "American actions and the flow of events have elevated the authority of the Jihadi insurgents and tended to ratify their legitimacy among Muslims, identifying both U.S. support of Israel and the American occupation of Iraq as examples."70 A 2006 National Intelligence Estimate concluded "the American invasion and occupation of Iraq . . . helped spawn a new generation of Islamic radicalism."71 A 2011 study of terrorist plots against the United States between 2001 and 2010 by the Los Angeles division of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) found the same: "Two central themes galvanized actors: anti-U.S. sentiment based on a perception that the United States was at war with Islam, and the belief that violent jihad was the righteous, and in fact, requisite response."72 And finally, a 2012 study by the FBI concluded that the number-one motivation for homegrown terrorist attacks in the United States was radicalization caused by anger at American military intervention against Middle Eastern nations.73

Finally, American leaders also fell prey to the conceit that they could reshape the politics of other nations. Both the Bush and Obama administrations believed that terrorism emerges, in part or whole, from factors such as poverty, deprivation, and an inability to engage in the political process. Although academic research reveals these assumptions to be flawed, the notion that the United States will not be safe from terrorism until the Middle East is stable, prosperous, and democratic has been a motivating principle behind America’s longer-term strategy of regime change and nation building.74

Although it might benefit the United States if Middle Eastern countries evolved into Western-style democracies, there is no evidence that the United States itself can play a determining role in making it happen, especially via military intervention. The results to date from Afghanistan and Iraq suggest that not even massive American intervention is enough to ensure permanent, positive change.75

The real question is why anyone in the United States believes that it would be possible for Americans to reshape Middle Eastern governments and societies. The U.S. track record of military intervention in civil conflicts is long and tragic. Well before Afghanistan and Iraq, the United States imagined it could impose political solutions on the Philippines, Vietnam, and the Dominican Republic, just to name a few failures. Nor does military victory improve the odds. The results of efforts to impose democracy via military means are dismal.76 Postwar nation building, especially by outside powers mistrusted (or actively opposed) by local populations, likewise has a poor track record.77

The notion that the United States could topple Saddam Hussein, for example, and then impose a new political system and an effective (and nonsectarian) new military force was a dangerous fantasy. The United States often fails to achieve desired outcomes in its own domestic matters. It is difficult to see why U.S. officials have imagined they would succeed in achieving sweeping outcomes in another nation’s political system.

Stepping Back from the War on Terror

How should these lessons from the failure of the War on Terror inform President Trump’s strategy for confronting ISIS and Islamist-inspired terrorism moving forward?

The United States confronts three basic strategic options for dealing with ISIS, al Qaeda, and future variants of jihadist terrorism. First, the United States can maintain the current course. The goal of such a strategy would be to contain and eventually defeat (or simply outlast) ISIS and other groups by continuing to rely heavily on local partners and without introducing much, if any, additional American firepower into the conflict.

Those who favor the "steady on" approach tend to view terrorism as a moderate-sized threat and believe that the current strategy is slowly but steadily making progress against ISIS. This group generally agrees that major American intervention was counterproductive and believes local forces are the best suited to fight ISIS, but sees an important supporting role for the United States.78 Until Trump’s election, the weight of establishment opinion on both the right and left appeared to be roughly in line with the strategy followed by the Obama administration, with debate occurring over relatively minor adjustments to the strategy such as humanitarian corridors or no-fly zones.

Second, the United States could choose to step up the fight. The goal of this strategy would be to increase — significantly — the American commitment to the maintenance of security and stability in Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria, and perhaps even Libya and Yemen. By bringing enough firepower and pressure to bear, supporters argue, the United States could destroy the Islamist-inspired terrorism threat, encourage the development of peaceful political systems, and prevent the reemergence of terrorism.

Despite widespread support for the status quo there is also a substantial minority that favors stepping up the fight against ISIS.79 While the president’s rhetoric suggests little interest in nation building abroad, both his campaign promises and operating style indicate expanded military efforts in the War on Terror are likely. Those who prefer this option believe that the terrorism threat is large enough to justify a great deal more effort than the United States is currently making. Former National Security Adviser General Michael Flynn, for example, has written that the fight against terrorism is a world war.80 Like Flynn, most supporters for stepping up the fight believe that the current strategy is ineffective.

The reasons given for the failure so far vary, but many believe that the central problem has been the unwillingness of the United States to commit enough military and political capital. The answer, from this view, is that the United States should do much more in the Middle East and surrounding region, including both bringing additional military pressure to bear and continuing the nation-building efforts in Afghanistan, Iraq, and elsewhere. Members of a bipartisan group, including retired Generals McChrystal and Petraeus, for example, recently called on the United States to make a "generational commitment" to Afghanistan and to invest substantially more in order to ensure security and stability there.81

Our analysis, however, clearly illustrates that the United States should rule out both the step-up option and the steady-on option. Neither ISIS nor the broader problem of Islamist-inspired terrorism represents enough of a threat to justify an expansive, aggressive, and costly series of overseas campaigns. Even under Obama, the "light footprint" approach continued to put thousands of Americans at risk carrying out nation building and terrorist killing missions that produce more problems than they solve, all at enormous financial cost.

Instead, the United States should take a step back from the fight. Though we do not attempt here to consider all of the potential strategies or tactics, we argue that the right general direction for the United States is to reduce the level of military intervention, suspend efforts at nation building, and end direct efforts to dictate political outcomes in the Middle East. This approach would seek to reduce the incentive for anti-American terrorism by disengaging from what are primarily civil wars in the Middle East.

Although the eventual details will depend on many factors, the Trump administration should embrace four main recommendations as it rethinks U.S. strategy:

1. Redefine the Objectives of the Fight against Terrorism to Align with the Limited Nature of the Threat

In recognition that terrorism is a far more limited threat than U.S. officials have generally acknowledged, the first thing policymakers should do is right-size the goals of American counterterrorism strategy. Specifically, the United States must abandon the goal of destroying al Qaeda, its various affiliates, and ISIS, and the fantasy of eradicating the causes of terrorism. In addition, the United States should scale back its efforts to deny sanctuary to terrorist organizations, which have proven similarly hapless. The United States cannot rid the world of all terrorist organizations, eliminate the conditions that give rise to terrorism, nor can it prevent small groups from finding safe havens. As the past 15 years have made clear, the United States does not need to do any of these things to maintain a high level of security. Homeland security efforts may or may not have been necessary to prevent many attacks at home, but unlike foreign intervention, they did not make things worse.

Instead of seeking victory in a War on Terror, the United States should work to manage the threat of terrorism, narrowing its counterterrorism strategy to focus primarily on the defense of the homeland. Intelligence services should continue to monitor global networks to track possible threats from terrorist organizations abroad but, since 2001, those threats have come overwhelmingly in the form of individuals who already live in the United States and are not members of al Qaeda or ISIS. In contrast to fighting a war on terrorism, the strategic management of terrorist threats requires recognizing that some amount of anti-American terrorism is inevitable. Although this is unpleasant to acknowledge, it is a necessary starting point for an effective strategy.

2. End Direct Military Intervention and Nation Building in the Greater Middle East

The narrower goal of homeland defense does not require the United States to pursue the complete destruction of foreign terrorist organizations, the assassination of individual terrorist leaders, or the prevention of negative political and military outcomes in the Middle East or North Africa. Thus, the United States should withdraw its troops from Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria, and other nations. It should also end the drone campaigns carried out as part of the War on Terror throughout the region. Although there may be situations in the future that warrant direct military intervention against a terrorist organization, military strikes should not be a regular part of U.S. counterterrorism strategy.

Likewise, the United States should cease coercive efforts to promote democracy and nation build in the Middle East. The military intervention and subsequent occupation and intrusive political pressure required for such efforts have created chaos and resentment and fueled additional terrorism, as events in Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya, Syria, and Yemen attest. And despite 15 years and an enormous investment of money and lives, U.S. efforts in Afghanistan and Iraq have produced little progress toward long-term peace and stability. There is little evidence that another 15 years will produce anything different.

Advocates of intervention on both the left and the right will complain that such a withdrawal carries too much risk. It is certainly true that an American withdrawal will put added pressure on local actors to confront jihadist organizations. In the short run, especially, this may allow ISIS and various al Qaeda franchises the ability to function more freely. In the case of Afghanistan, it may even pave the way for the Taliban to retake nominal control of the country if the current government cannot secure its own territory.

These objections ring hollow, however, in light of the American experience since 9/11. A decade and a half’s worth of evidence shows that the interventionist camp’s confidence in the effectiveness of military intervention is misplaced. Fifteen years of significant efforts have failed to stabilize the region or diminish the jihadist enterprise. Instead, the visible and militarized presence of the United States has helped feed the growth of terrorism and anti-American sentiment throughout the Middle East. Pulling U.S. troops out of the region, ending drone strikes, and withdrawing from the direct fight against ISIS will not only reduce casualties that stem from the military campaign, but may further reduce the likelihood of future terrorist attacks against the United States.

3. Support Regional Partners to Take the Lead in Confronting Terrorism through Indirect and Multilateral Channels

Terrorism is not a big enough threat to warrant direct American military intervention. The United States should make it clear to its Middle Eastern partners that, although the United States opposes ISIS and supports the development of open societies in the Middle East, the tasks of dealing with terrorism and governance are regional responsibilities.

What support the United States does provide, however, should be indirect and, whenever possible, should be provided through the United Nations or other multilateral institutions in order to defuse the "West versus Islam" narrative that the War on Terror has unfortunately reinforced. The fewer obvious signs of Western presence in the Middle East there are, the clearer it will be that the clash is not between the West and Islam, but between factions fighting for control of the Middle East.82

4. Return to an Emphasis on the Intelligence and Law Enforcement Paradigm for Dealing with Terrorism

Fighting wars is a job for the Pentagon and the military services. Fighting terrorism, on the other hand, has historically been a job for the intelligence services and law enforcement agencies.83 American military operations in the Middle East have done little to reduce the incidence of Islamist-inspired lone-wolf terrorism here in the United States and have likely led to a higher incidence of such attacks. Instead, the United States should focus on the difficult work of assessing emerging threats and interrupting them in the planning cycle through intelligence and police work, not military intervention.

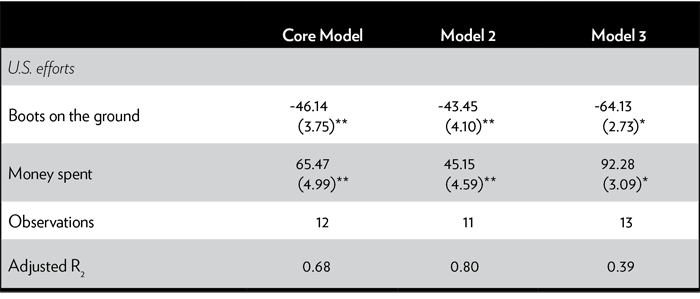

Coefficients listed, absolute value of t statistics in parentheses. Asterisks (*, **) indicate significance at the 5 percent and 1 percent level, respectively. All regressions include an intercept (not reported).

Conclusion

America has a successful track record regarding homeland security. Although critics have rightly pointed out gaps and inefficiencies, there have been very few successful terrorist attacks in the United States since 2001. Even fewer attacks have caused casualties and, in all cases, the perpetrators have been killed or arrested in short order. Homeland security can never promise perfect security, and acknowledging this is difficult, especially politically. But it is clear that adopting aggressive military strategies that falsely promise zero risk have failed. It is time to turn the page in the War on Terror.

By adopting a more modest goal of managing the terror risk, the United States can reduce the likelihood of future attacks through continued homeland security efforts that rely on law enforcement and intelligence agencies. By embracing a less militaristic and less interventionist approach, the United States can avoid repeating the dangerous and very costly mistakes of the past 15 years.

Appendix 1. Regression Analysis

To investigate the impact of U.S. military intervention we created regression models to examine the significance, if any, of U.S. military actions in the War on Terror while controlling for other variables often used in the study of terrorism, such as a state’s GDP per capita, economic growth rate, social fractionalization, polity, and education levels. The discussion below provides additional detail on two statistical analyses of the relationship between United States intervention and levels of terrorism around the world.

In the Core Model of our first analysis (see Figure A1), the dependent variable is the number of terror attacks worldwide. The explanatory variables are the money spent by the U.S. government each year in the War on Terror (in billions of dollars) and the number of U.S. troops deployed to fight the War on Terror each year (in thousands). Money spent was lagged by one year to compare the money spent in time period t with the number of terror attacks in time period t + 1. For Model 2, money spent was lagged by two years. In Model 3, neither variable was lagged. Money spent was lagged in the core and second model because spending money is estimated to have a delayed impact. By lagging the variable, the model was able to take into account the time needed for money to work its way through the system and produce an effect. Boots on the ground were thought to have a more immediate impact, so that variable was not lagged.

Figure A1: U.S. War on Terror and Level of Terror Attacks

Notes: Dependent variable: number of global terror attacks

In all three runs (i.e., Core, Model 2, and Model 3), both variables were statistically significant following common practice in political science and public policy research. Statistical significance refers to the likelihood that a relationship exists between an independent variable and the dependent variable. In this case, the model is estimating the relationship between U.S. efforts (boots on the ground and money spent) and the number of terror attacks worldwide (i.e., the dependent variable). The asterisks above indicate a reader can be 95 or 99 percent confident that each variable is related to the number of terror attacks worldwide. Conversely, that means there is a 1 or 5 percent chance that there is actually no relationship between the respective independent variables and the dependent variable.

The results indicate that the core model explains 68 percent of the variation in the number of worldwide terror attacks, Model 2 explains 80 percent, and Model 3 explains 39 percent. In the aggregate, spending more money and sending more military personnel has been associated with an increase in the number of terror attacks.

In order to control for other factors that scholars believe may be related to terrorism, our second analysis involved an expanded set of variables (see Figure A2). The explanatory variables are listed in the first column. The dependent variable is the number of terror attacks worldwide for the core and second model. For the final model, "Number of Islamist FTOs," the dependent variable is the number of Islamist foreign terrorist organizations as identified by the Department of State.

To achieve the core model, the model was run with all 12 variables, the most insignificant variable was deleted, and then the model was run again. This process was repeated until all remaining independent variables were statistically significant. Unexpectedly, the results indicate that regime type and education are positively related to the number of terror attacks, all else being equal. This suggests that, as either the population receives more education or the country transitions away from autocracy, the number of terror attacks will increase. Additionally, the results indicate that if the United States invaded a country or conducted drone/air strikes in a country, the number of terror attacks dramatically increased in those countries. Being invaded by the United States is associated with an increase of 143 terror attacks per year, while having drone/air strikes carried out by the United States in your country is associated with an increase of 395 terror attacks per year. The results indicate that the six variables in the core model explain 43 percent of the variation in the number of terror attacks. It is important to note that the political/civil rights variable is scored by Freedom House such that an increasing score is a sign of worsening political/civil rights. Therefore, the positive relationship observed in the model between political/civil rights and terrorism suggests that worsening rights are associated with an increase in terrorism (as would be expected).

The second model reflects all 12 variables. The results are largely similar to the core model. The results indicate that the 12 variables in the model explain 53 percent of the variation in the number of terror attacks.

In the final model, the dependent variable was changed. Instead of examining the number of terror attacks worldwide, the dependent variable is now the number of Islamist-inspired foreign terrorist organizations as identified by the U.S. Department of State. Eleven of the 12 independent variables are included. Of note, the number of years in the War on Terror is related

Figure A2: Causes of Terrorism and U.S. Efforts

Note: Coefficients listed, absolute value of t statistics in parentheses. Asterisks (*, **) indicate significance at the 5 percent and 1 percent level, respectively. All regressions include an intercept (not reported).

to an increase in the number of Islamist-inspired foreign terrorist organization. Additionally, education and polity continue to be significant and in the unexpected direction. The results suggest that, as either of those two areas improves, the number of Islamist-inspired terror groups increases, too. The results indicate that the 11 variables in the model explain 65 percent of the variation in the number of Islamist-inspired FTOs over time.

Notes

The authors thank Captain Maxwell Pappas, U.S. Army, for his valuable research and insights as the project took shape.

- "Trump: I’m Going to Bomb ISIS," YouTube video, November 13, 2015, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6_35yJpVyAA.

- "Full Text: Donald Trump’s Speech on Fighting Terrorism," August 15, 2016, http://www.politico. com/story/2016/08/donald-trump-terrorism-speech-227025.

- Ibid.

- Neta Crawford, "U.S. Budgetary Costs of Wars through 2016: $4.79 Trillion and Counting," Brown University, September 2016.

- John Mueller and Mark Stewart, "Responsible Counterterrorism Policy," Cato Institute Policy Analysis no. 755, September 10, 2014. Also see Tammy O. Tengs et al., "Five-Hundred Life-Saving Interventions and Their Cost-Effectiveness," Risk Analysis 15, no. 3 (1995): 369–90. The authors studied 587 life-saving interventions in the United States and found that the median cost of saving a life was roughly $3.4 million, or about the cost of two Tomahawk cruise missiles. From a more global perspective, a mere $2 billion of the annual War on Terror funding could save the lives of all 600,000 people who die from Malaria each year. See Chris Weller, "The World’s Best Charity Can Save a Life for $3,337.06," Business Insider, July 29, 2015, http://www.businessinsider.com/the-worlds-best-charity-can-save-a-life-for-333706-and-thats-a-steal-2015-7/.

- Bradford Ian Stapleton, "The Problem with the Light Footprint: Shifting Tactics in Lieu of Strategy," Cato Institute Policy Analysis no. 792, June 7, 2016.

- Others making some form of this argument include Barry Posen, Restraint: A New Foundation for U.S. Grand Strategy (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2015); Andrew Bacewich, America’s War for the Greater Middle East: A Military History (New York: Random House, 2016); Graham T. Allison, "Deterring ISIS," The National Interest, September/October 2016, pp. 5–10; and Michael Mandelbaum, Mission Failure: America and the World in the Post–Cold War Era (New York: Oxford University Press, 2016).

- Although domestic policies and legislation such as the Patriot Act and the creation of the Department of Homeland Security have certainly played a significant role in the response to terrorism, we focus here on the critical lessons for the fight against Islamist-inspired terrorism that stem from what the United States has done outside the homeland. Our analysis therefore focuses on those efforts and leaves the assessment of domestic counterterrorism policies to others. See, for example, John Mueller and Mark G. Stewart, Terror, Security, and Money: Balancing the Benefits, Risks, and Costs of Homeland Security (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011); and John Mueller and Mark G. Stewart, Chasing Ghosts: The Policing of Terrorism (New York: Oxford University Press, 2016).

- White House, "National Strategy for Combating Terrorism," (2003), p. 11; and White House, "National Strategy for Counterterrorism," (2011), p. 9.

- White House, "National Strategy for Counterterrorism," (2011), pp. 15–28.

- See, for example, President Bush’s speech at the International Conference on Financing for Development, March 22, 2002, http://www.un.org/ffd/statements/usaE.htm; his speech before the National Endowment for Democracy on October 6, 2005, https://georgewbush-whitehouse.archives.gov/news/releases/2005/10/20051006-3.html; and President Obama’s National Strategy for Counterterrorism, June 2011, https://www.hsdl.org/?view&did=487985.

- Joint Staff, "Joint Publication 3-0: Joint Operations" (2011), p. GL-13.

- White House, "The National Security Strategy of the United States" (2002), pp. 6, 15.

- Bob Woodward, Bush at War (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2003), pp. 19–20. On the administration’s new attitude toward dealing with potential threats more generally, see Ron Suskind, The One Percent Doctrine: Deep Inside America’s Pursuit of Its Enemies Since 9/11 (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2006).

- George W. Bush, "Remarks at the American Legion National Convention in Reno, Nevada," August 28, 2007, http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/index.php?pid=75688.

- "Talking Points for Rumsfeld-Franks Meeting," November 27, 2001, National Security Archive, George Washington University, http://nsarchive.gwu.edu/NSAEBB/NSAEBB326/index.htm; Lee Hamilton and Justine A. Rosenthal, eds., State of the Struggle: Report on the Battle against Global Terrorism (Washington: Council on Global Terrorism, 2006), p. 42; "President Bush’s Speech on the War on Terrorism," United States Naval Academy, November 30, 2005, http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2005/11/30/AR2005113000667.html.

- Helene Cooper, "U.S. Conducts Airstrikes against ISIS in Libya," New York Times, August 1, 2016; and "How the U.S. Became More Involved in the War in Yemen," New York Times, October 15, 2016, http://www.nytimes.com/interactive/ 2016/10/14/world/middleeast/yemen-saudi-ara bia-us-airstrikes.html.

- Micah Zenko, Reforming U.S. Drone Strike Policies (New York: Council on Foreign Relations, 2013), p. 8, http://www.cfr.org/wars-and-warfare/reforming-us-drone-strike-policies/p29736.

- White House, "National Security Strategy" (February 2015), p. 10.

- Bob Woodward, Plan of Attack: The Definitive Account of the Decision to Invade Iraq (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2004), p. 88.

- Raphael Perl, "Combating Terrorism: The Challenge of Measuring Effectiveness," Congressional Research Service, November 23, 2005, p. 4.

- Hamilton and Rosenthal, State of the Struggle, p. 83.

- White House, "National Strategy for Combating Terrorism" (2003), p. 22; White House, "National Security Strategy of the United States" (2006), p. 1; White House, "National Strategy for Combating Terrorism" (2006), pp. 9, 11, https://fas.org/irp/threat/nsct2006.pdf; and White House, "National Strategy for Counterterrorism" (2011), p. 8, https://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/counterterrorism_strategy.pdf. See also Jonathan Monten, "The Roots of the Bush Doctrine: Power, Nationalism, and Democracy Promotion in U.S. Strategy," International Security 29, no. 4 (Spring 2005): 148–49.

- Kenneth Katzman, "Iraq: Politics, Security, and U.S. Policy," Congressional Research Service, June 22, 2015, p. 10.

- Kenneth Katzman, "Afghanistan: Post-Taliban Governance, Security and U.S. Policy," Congressional Research Service, 2015, pp. i, 31.

- Amy Belasco, "The Cost of Iraq, Afghanistan, and Other Global War on Terror Operations Since 9/11," Congressional Research Service, December 8, 2014, p. 62.

- "Much of $60B from U.S. to Rebuild Iraq Wasted, Special Auditor’s Final Report to Congress Shows," CBSnews.com, March 6, 2013, http://www.cbsnews.com/news/much-of-60b-from-us-to-rebuild-iraq-wasted-special-auditors-final-report-to-congress-shows/; Elias Groll, "The United States Has Outspent the Marshall Plan to Rebuild Afghanistan," Foreign Policy, July 30, 2014, https://foreignpolicy.com/2014/07/30/the-united-states-has-outspent-the-marshall-plan-to-rebuild-afghanistan/.

- Erik W. Goepner, "Measuring the Effectiveness of America’s War on Terror," Parameters 46, no. 1 (Spring 2016): 107–20.

- John Mueller and Mark Stewart, "American Public Opinion Trends since 9/11: Trends and Puzzles," paper presented at International Studies Association, March 2016.

- Data are from the National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism (START), "Global Terrorism Database, 2016," (globalterrorismdb_0616dist.xlsx), http://www.start.umd.edu/gtd.

- Ibid.

- Data are from Federal Bureau of Investigation, "Crime in the United States, 2015," https://ucr.fbi.gov/crime-in-the-u.s/2015/crime-in-the-u.s.-2015/tables/table-1.

- National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism, "Global Terrorism Database"; and FBI, "Crime in the United States, 2015."

- Making this argument, for example, is John Mueller, Overblown: How Politicians and the Terrorism Industry Inflate National Security Threats, and Why We Believe Them (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2006).

- On Osama bin Laden’s early calls for U.S. forces to leave the region, see, for example, his 1996 "Declaration of War against the Americans Occupying the Land of the Two Holy Places." An English translation is available from Masaryk University, "Osama bin Laden’s Fatwa 1996," https://is.muni.cz/el/1423/jaro2010/MVZ203/OBL___AQ__%20Fatwa_1996.pdf.

- Steven Brill, "15 Years After 9/11, Is America Any Safer?" The Atlantic, September 2016, pp. 1–28; Kevin Strom et al., "Building on Clues: Examining Successes and Failures in Detecting US Terrorist Plots, 1999–2009," Institute for Homeland Security Solutions, 2010; and Erik J. Dahl, "The Plots That Failed: Intelligence Lessons Learned from Unsuccessful Terrorist Attacks against the United States," Studies in Conflict & Terrorism 34, no. 8 (2011): 621–48.

- David Inserra, "Attack at Ohio State Brings U.S. Terror Plots, Attacks to 93 Since 9/11," Daily Signal, Heritage Foundation, November 30, 2016, http://www.dailysignal.com/2016/11/30/attack-at-ohio-state-brings-us-te…. Many observers have argued even the 93 attempts is an inflated measure of the threat. See, for example, Mueller, Overblown; and Trevor Aaronson, The Terror Factory: Inside the FBI’s Manufactured War on Terrorism (New York: Ig Publishing, 2013).

- Stephen Flynn, The Edge of Disaster: Rebuilding a Resilient Nation (New York: Random House, 2007); Mueller and Stewart, Terror, Security, and Money; and Charles Perrow, "The Disaster After 9/11: The Department of Homeland Security and the Intelligence Reorganization," Homeland Security Affairs 2, no. 1 (2006): 1–28.

- George Tenet and Bill Harlow, At the Center of the Storm (New York: Harper Perennial, 2007).

- Mueller and Stewart, Chasing Ghosts, p. 107.

- Ibid., p. 108.

- Global Terrorism Database, dataset June 2015.

- Ibid.

- The largest of these was the Camp Speicher massacre in Tikrit, Iraq, in June 2014, during which the Islamic State executed as many as 1,700 Shia Iraqi Air Force cadets. On the massacre see Omar Al-Jawoshy and Tim Arango, "Iraq Executes Dozens for 2014 Massacre by ISIS," New York Times, August 21, 2016. Terrorism data are from the Global Terrorism Database, https://www.start.umd.edu/gtd.

- BBC News, "Paris Attacks: What Happened on the Night," December 9, 2015, http://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-34818994.

- Among those making arguments in this vein, see, for example: Daniel Byman and Jennifer Williams, "ISIS vs. Al Qaeda: Jihadism’s Global Civil War," February 24, 2015, https://www.brookings.edu/articles/isis-vs-al-qaeda-jihadisms-global-civil-war/; and William McCants, The ISIS Apocalypse: the History, Strategy, and Doomsday Vision of the Islamic State (New York: Picador, 2015).

- On the growth in the use of terrorism, see Institute for Economics and Peace, "Global Terrorism Index 2016." On the rise of ISIS, see McCants, The ISIS Apocalypse.

- Council on Foreign Relations, "Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula," June 19, 2015, http://www.cfr.org/yemen/al-qaeda-arabian-peninsula-aqap/p9369.

- Data on militant forces are from the Mapping Militant Organizations project at Stanford University, http://web.stanford.edu/group/mappingmilitants/cgi-bin/; and from the United States Department of State, "Country Reports on Terrorism 2015," June 2016.

- See Appendix 1 for a complete discussion of the regression results.

- White House, "National Strategy for Combating Terrorism," (2003), p. 23.

- Ibid., pp. 23–24.

- White House, "National Strategy for Counterterrorism," (2011), pp. 9–10, https://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/counterterrorism_strategy.pdf.

- A comprehensive assessment of the worsening of these conditions can be found in Anthony Cordesman, "Defeating ISIS: The Real Threats and Challenges," Center for Strategic and International Studies, August 4, 2016.

- Data are derived from Transparency International’s "Corruption Perception Index," http://www.transparency.org/country.

- Of the seven countries, only Pakistan has moved from the worst category up to "partly free." However, the average score for the seven countries improved from 6.6 to 6.1 (6 = "very restricted"; the scale is from 1 to 7 with a one representing most free). See Freedom House, "Freedom in the World, 2016," https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-world/freedom-world-2016.

- Center for Systemic Peace, "State Fragility Index," at http://www.systemicpeace.org/inscrdata.html.

- On the psychological response to terrorism, see, for example: Daniel Kahneman, Thinking, Fast and Slow (New York: Macmillan, 2011): 322–34; Randall Marshall et al., "The Psychology of Ongoing Threat: Relative Risk Appraisal, the September 11 Attacks, and Terrorism-Related Fears," American Psychologist 62, no. 4 (2007): 304; and Leonie Huddy et al., "The Consequences of Terrorism: Disentangling the Effects of Personal and National Threat," Political Psychology 23, no. 3 (2002): 485–509.

- Mueller, Overblown; Bruce Schneier, Beyond Fear: Thinking Sensibly about Security in an Uncertain World (New York: Springer Science & Business Media, 2006).

- Mary Habeck et al., "A Global Strategy for Combating al Qaeda and the Islamic State," American Enterprise Institute, December 2015. By way of illustration, this report begins with the following sentence: "The United States faces a fundamental challenge to its way of life."

- Useful summaries of terrorism that provide an informed historical perspective include: Bruce Hoffman, Inside Terrorism (New York: Columbia University Press, 2006); and David Rapoport, "The Fourth Wave: September 11 in the History of Terrorism," Current History 100 (2001): 419–24.