Learn more about Cato’s Amicus Briefs Program.

The Supreme Court has repeatedly stated that the Eighth Amendment “does not mandate comfortable prisons, but neither does it permit inhumane ones.” During his time in prison, Trent Taylor, a Texan inmate, was subjected to exactly the sort of inhuman conditions that violate the Eighth Amendment. Following a suicide attempt, Taylor was transferred a psychiatric prison unit for mental health treatment. Instead of providing that treatment, prison officials stripped Taylor of his clothing, including his underwear, and placed him in a cell where almost every surface—including the floor, ceiling, windows, and walls—was covered in “massive amounts” of human feces belonging to previous occupants. Taylor was unable to eat because he feared that any food in the cell would become contaminated, and feces “packed inside the water faucet” prevented him from drinking water for days. The prison officials were well aware of these conditions, and at one point laughed that Taylor was “going to have a long weekend.”

Four days later, prison officials moved Taylor to a different “seclusion cell.” Other inmates referred to this cell as “the cold room” because of its frigid temperature. The cell had no toilet, water fountain, or furniture. It contained only a drain on the floor, which was clogged, leaving a standing pool of raw sewage in the cell. Because the cell lacked a bunk, Taylor had to sleep on the floor, naked and soaked in sewage, with only a suicide blanket for warmth. Taylor was kept in this cell for three days and never allowed to use a restroom. He attempted to avoid urinating on himself to avoid adding to the pool of sewage in which he had to sleep, but he eventually involuntarily urinated on himself. As a result of holding his urine in a bacteria-laden environment for an extended period, Taylor developed a distended bladder requiring catheterization.

Taylor filed suit against a number of prison officials involved in his mistreatment, alleging Eighth Amendment violations stemming from his unsanitary conditions and denial of treatment. The Fifth Circuit held that Taylor had established a genuine factual dispute as to whether the defendants violated the Eighth Amendment by confining Taylor in “squalid cells” for nearly a week. The court explained that the “risk posed by Taylor’s exposure to bodily waste was … especially obvious here, as [defendants] forced Taylor to sleep naked on a urine-soaked floor,” and “failed to remedy the paltry conditions.” Nevertheless, the court found that the law on this point was not “clearly established,” and therefore granted qualified immunity to the prison officials. The court observed that while “the law was clear that prisoners couldn’t be housed in cells teeming with human waste for months on end,” it had not previously held that confinement in human waste for six days violated the Constitution.

This case is yet another illustration of the absurdity and injustice of the “clearly established law” standard that characterizes modern qualified immunity doctrine. Under this standard, whether individuals can get relief for constitutional violations by government agents turns not on whether the rights were violated, nor even on whether the defendants were acting in good faith (as these officers obviously were not), but simply on the happenstance of what cases have already been decided in a particular jurisdiction. Even the Supreme Court has said that cases on point are not required for “obvious” constitutional violations, and it is hard to imagine what could be more obviously inhumane conditions than forcing an inmate to live and sleep naked in rooms covered in human waste.

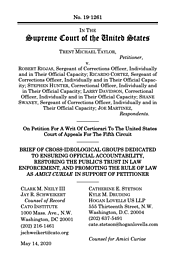

Cato filed an amicus brief on behalf of a cross‐ideological alliance of a dozen different public policy groups, which also included the ACLU, Alliance Defending Freedom, American Association for Justice, Americans for Prosperity Foundation, Due Process Institute, Law Enforcement Action Partnership, NAACP Legal Defense Fund, Physicians for Human Rights, Public Justice, R Street Institute, and the Second Amendment Foundation. This brief argues that the Supreme Court should reconsider qualified immunity entirely, as the doctrine lacks any valid legal basis, vitiates the power of individuals to vindicate their constitutional rights, and contributes to a culture of near‐zero accountability for law enforcement, prison personnel, and other public officials.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.