Learn more about Cato’s Amicus Briefs Program.

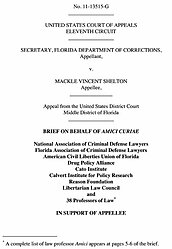

Florida is so zealous in pursuing the war on drugs that its laws classify the possession, sale, and delivery of controlled substances as offenses not requiring the state to prove that the defendant knew he had possessed, sold, or delivered those substances. In the current case, state prosecutors convicted Mackie Shelton of transporting cocaine under one of these “strict liability” statutes, the trial judge having instructed the jury that the state only needed to prove that Shelton delivered a substance and that the substance was cocaine. Shelton successfully challenged the constitutionality of that state law in federal court, where the district judge overturned the conviction and noted that “Florida stands alone in its express elimination of mens rea as an element of a drug offense.” Florida appealed that ruling to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit. Cato has joined the National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers, Florida Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers, ACLU, Drug Policy Alliance, Calvert Institute for Policy Research, and 38 law professors in a brief supporting Shelton’s position. The Supreme Court has recognized only limited exceptions to the general rule that criminal culpability requires mens rea (a guilty mind). These “strict liability” crimes fall under the rubric of “public welfare offenses” and are typically what most people would not consider “serious,” such as traffic violations and selling alcohol to minors. Policymakers justify dispensing with mens rea requirements in such contexts by citing the need to deter businesses from imposing costs on society at large, or the burden that having to prove mens rea in these sorts of cases would overwhelm courts, or that the penalties are relatively small and carry little social stigma. Florida’s legislature, however, went well beyond the normal boundaries of public welfare offenses in imposing strict liability for drug crimes that can carry significant prison terms — and thus violated the due process of law and traditional notions of fundamental fairness. As an alternative argument purporting to save its drug laws, Florida points to the availability of affirmative defenses, that these defenses (e.g., “I didn’t know it was cocaine”) to a presumption of guilty intent take the statute out of the (constitutionally dubious) strict liability category. But a state may not simply presume the mens rea element of a crime: In Patterson v. New York (1977), for example, the Court held that prosecutors cannot reallocate the burden of proof by forcing a defendant to prove an affirmative defense. In requiring defendants to prove that they are “blameless” in these sorts of drug crimes, Florida’s statutes fail constitutional muster. We urge the Eleventh Circuit to affirm the district court and declare the offending state law unconstitutional.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.