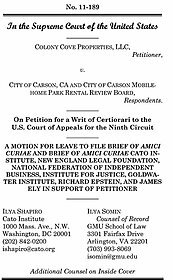

Colony Cove Properties v. City of Carson

Learn more about Cato’s Amicus Briefs Program.

When state and local governments violate federal constitutional rights (e.g., First Amendment free speech), they can be sued in federal court — except when that government action violates the Fifth Amendment’s protections for property rights. Under the Supreme Court’s decision in Williamson County v. Hamilton Bank, individuals and businesses alleging unconstitutional takings by state or local governments are required to exhaust state review procedures — seeking redress from the very officials who harmed them — before turning to federal courts. This constitutional anomaly is evident in Colony Cove v. Carson, where the operators of a rental property in California alleged an unconstitutional taking when the local rent control board refused to approve an increase in rent to allow their business to operate profitably. California law forecloses judicial review of the findings of rent control boards, so municipal governments have an unchecked license to determine whether such businesses may operate: A property owner’s sole recourse is to appeal to the very rent control board who forbade her from charging a profitable rent in the first place. These “review” procedures, like some others across the nation, are wildly insufficient. Even more significantly, once a takings claim has been fully heard in state proceedings per Williamson County’s command, it is usually barred from federal review based on various prudential doctrines. The result is the indiscriminate exclusion of takings claims from federal courts, a situation that invites opportunist states to usurp private property rights. Seeking to afford citizens across the nation the opportunity to assert Takings Clause claims in parity with other constitutional rights, Cato joined the New England Legal Foundation, National Federation of Independent Business, Institute for Justice, Goldwater Institute, and Professors James Ely and Richard Epstein in filing an amicus brief supporting the California property owners’ petition for Supreme Court review of the Ninth Circuit’s ruling against them. We argue that Williamson County should be overruled because it relegates takings claims to second-class status despite the constitutional first principle that uniform protection of individual rights is vital to our system of government. At the very least, the Court should require federal reprieve when state procedures for rectifying a taking are futile — as they were here. Finally, we argue that the Court should correct lower courts’ misinterpretation of Williamson County, which puts property rights jurisprudence at odds with Section 1983 of the Civil Rights Act of 1871 (a statute that gives people access to federal courts when a state denies them their constitutional rights).

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.