Carpenter v. United States

Learn more about Cato’s Amicus Briefs Program.

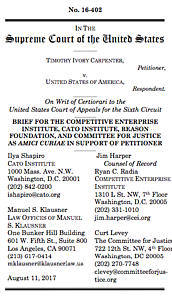

Timothy Carpenter and Timothy Sanders were convicted in federal court on charges stemming from a string of armed robberies in and around the Detroit area. They appealed on the ground that the government had acquired detailed records of their movements through cell site location information (“CSLI”) from their wireless carriers in violation of the Fourth Amendment. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit turned their appeal aside, finding that “[t]he government’s collection of business records containing these data … is not a search.” The Fourth Amendment states that “[t]he right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated.” Presumably, when called on to determine whether a Fourth Amendment violation has occurred, courts would analyze the elements of this language as follows: Was there a search? Was there a seizure? Was any such search or seizure of “their persons, houses, papers, [or] effects”? Was any such search or seizure reasonable? And in cases involving familiar physical objects, they usually do. In harder cases dealing with unfamiliar items such as communications and data, however, courts retreat to the Supreme Court’s “reasonable expectation of privacy” doctrine that emerged from Katz v. United States (1967). The Court has decided to review the important criminal-procedure and digital-privacy issues here. Cato and the Competitive Enterprise Institute, joined by Reason Foundation and the Committee for Justice, filed an amicus brief urging the Court to return to the text of the Fourth Amendment. The reasonable expectation of privacy test is outdated because it lacks a strong connection to the text and asks courts to conduct a sociological exercise rather than a judicial one. This is especially true in the context of new technology, where societal expectations have not been fully formed yet and will change based on the Court’s judgment, leading to circular reasoning. Courts have also used the” reasonable expectation of privacy” test to undermine the very things the Fourth Amendment was designed to protect. For instance, dog sniffs looking for drugs have been said to not “compromise any legitimate interest in privacy” because they are only looking for contraband. But just because a search is designed to look for illegal activity doesn’t mean that the Fourth Amendment is inapplicable. Likewise with the “third-party doctrine,” which holds that constitutional protections stop when protected information is shared. This case deals with information about a person’s location for more than 100 days, and yet the government claims that no privacy is violated when it seizes and searches that data. The Court should return to the text of the Fourth Amendment and recognize that data and digital communication are property that are protected by the papers and effects part of the Fourth Amendment, as it did in Riley v. California—the 2014 case where the justices unanimously required a warrant for searching a phone seized during an arrest. Here, the government ordered the information on Mr. Carpenter’s location turned over (a seizure) and then processed that data for the location of the defendants (a search). The defendants had a contract with the phone company prohibiting the distribution of the data and the Court should recognize the property interest that the defendants had based on that contract. In sum, the Fourth Amendment presumes that a warrant is required but for exceptional circumstances. There was no exigency that threatens the destruction of the data here, threat to officer safety, or any other reason that law enforcement officers could not get a warrant if they had probable cause. Focusing on the actual text of the Fourth Amendment demonstrates that the government’s actions here violated the Fourth Amendment.