China's Steel Overcapacity Can Benefit the United States

China's "socialist market economy" has been driven far too much by socialist planning and not enough by the actual marketplace. Decisions at various levels of government within China have encouraged undisciplined investments in steel capacity, which have led to a large gap between China's ability to produce steel and the demand for it. Because much of the production increase has been generated by government policies, it is clear that China's steel exports aren't really "fair." However, a lot of things in life aren't fair — it's just necessary to make the best of them.

So the question of interest to policymakers should be: What policy response would allow the United States to make the best of those unfair circumstances, preferably turning them to America's advantage?

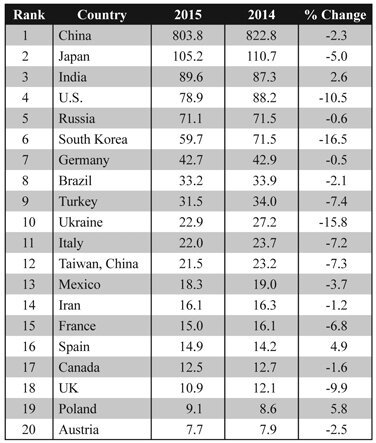

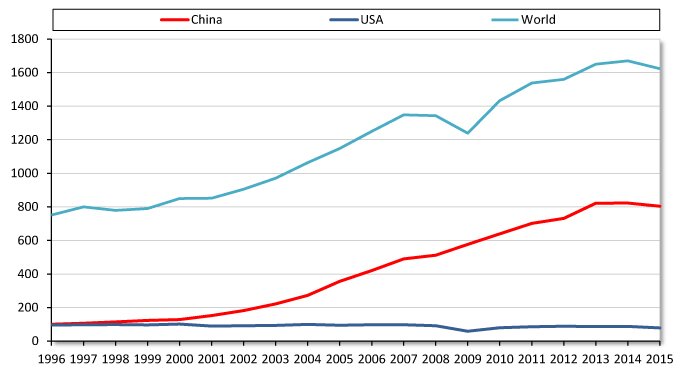

It is helpful to start by reviewing some realities of the political economy of China's steel market. Many Chinese steel mills never would have been built at all if those investors had been subject to the market pressures of a fully open and competitive economy. Earning a positive return on invested capital has not been an important objective for mills that are owned or heavily influenced by governments. As a consequence, capacity has been added for which there is no effective demand, either in China or overseas. Estimates of overcapacity worldwide (most of which is in China) range in excess of 600 million metric tons,1 equivalent to more than a third of annual global steel output.2 (See Figure 1 and Table 1.) Some of that capacity may close in the coming years, perhaps without ever having been operated profitably.

In the near term, however, China appears to be dealing with its unwise steel investments largely by making a second unwise decision — that is, operating many mills at a loss instead of just shutting them down. This is bad for China because it uses resources inefficiently. It also creates political complications for other countries, including the United States. However, the economics of the situation can work to America's benefit. Since China is selling steel for less than it would be worth in an economy guided solely by market forces, U.S. steel consumers are getting a bargain. China's decision to run its steel mills at negative rates of return means, in essence, that China is helping to increase the competitiveness of U.S. manufacturers that use steel as an input. In terms of the underlying economics, China takes the losses and the United States reaps the gains. What's not to like about those circumstances?

Table 1. Largest Steel Producing Countries, Million Metric Tons

Source: World Steel Association.

Figure 1. Crude Steel Production, 1996-2015, Million Metric Tons

Source: World Steel Association.

Trade Remedies Make the Situation Worse

Yes, domestic U.S. steel producers are exposed to unfairly low-priced steel and are understandably unhappy. Their traditional response has been to seek relief from troublesome imports, primarily by filing antidumping and countervailing duty (AD/CVD) petitions. There are two reasons that this approach does not serve the best overall interests of the United States.

One is that today's steel market for commodity products is so far out of balance that trade remedy measures simply can't bring the U.S. industry back to profitability. The global supply of commodity steel products is so large that prices are low worldwide. No matter how many trade remedy band-aids are placed on that wound, they won't raise U.S. prices sufficiently to stop the financial bleeding.

The other shortcoming of AD/CVD orders is that — even if they could provide some help to U.S. steel manufacturers — they would do great harm to downstream U.S. firms that use steel as an input. True, U.S. steel producers employ tens of thousands of people. But steel production adds far less value to the U.S. economy and employs far fewer people than do downstream manufacturers.

Data from the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) at the Department of Commerce indicate that value added by "primary metal manufacturing" amounted to $59.7 billion in 2014.3 (Note: Primary metal manufacturing [NAICS 331] includes nonferrous metals, such as copper, aluminum, magnesium, lead, tin, silver, and gold, so is much broader than the steel industry.) Downstream manufacturers that utilize steel as an input generate value added of $990 billion, more than 16 times larger than primary metal industries. The disparity in employment also is more than 16 times greater. Primary metal manufacturing employed 399,000 people in 2014.4 Downstream manufacturers employed 6.5 million. (Employment by U.S. steel producers is somewhere in the neighborhood of 100,000.)

The point is not that steel production is a small and insignificant industry, because clearly it is not. Rather, the point is that the problems of the steel industry need to be kept in perspective. It would be a poor policy choice to attempt to protect steel producers in ways that do much greater harm to steel users.

One of the sad realities is that AD/CVD orders can make the United States a relatively high-priced island in a world awash with lower-priced steel. Not having access to competitively priced inputs can lead quickly to sales losses for companies that manufacture goods containing steel. Overseas firms that benefit from lower costs will be able to export products to the United States and undersell U.S. manufacturers. So imposing trade remedies is a great way to reduce the economic welfare of the United States, thus making this country poorer.

One example might be Carrier, the company that recently announced it would shift manufacturing air conditioners from two plants in Indiana to Monterrey, Mexico. This decision, which will lead to the loss of 2100 jobs, has inspired commentary in the presidential campaign. The company's official statement does not attribute the change specifically to higher U.S. prices for key inputs covered by AD/CVD orders. However, the statement does say, "This move is intended to address . . . ongoing cost and pricing pressures."5 It seems likely that some of those cost pressures relate to U.S. trade remedies, 19 of which restrict imports of various steel products from China. (Not all of those steel products would be used in the manufacture of air conditioners.) Other AD/CVD orders apply to imports of copper tubing, which is an important component of air conditioning systems, as well as aluminum extrusions. If the United States wishes to create a more favorable business climate for manufacturers, a good start would be to revoke AD/CVD orders that raise the costs of their components. These are costs that Carrier largely can avoid by moving operations to Mexico.6

A Better Approach

What should be done instead of using trade remedies? U.S. policymakers should take advantage of fundamental economics. China's decision to export steel for less than it is worth has the effect of transferring wealth from China to the United States. As a practical matter, the best way to encourage China to downsize and restructure its industry would be to reframe the debate by communicating the following message to the Chinese government: