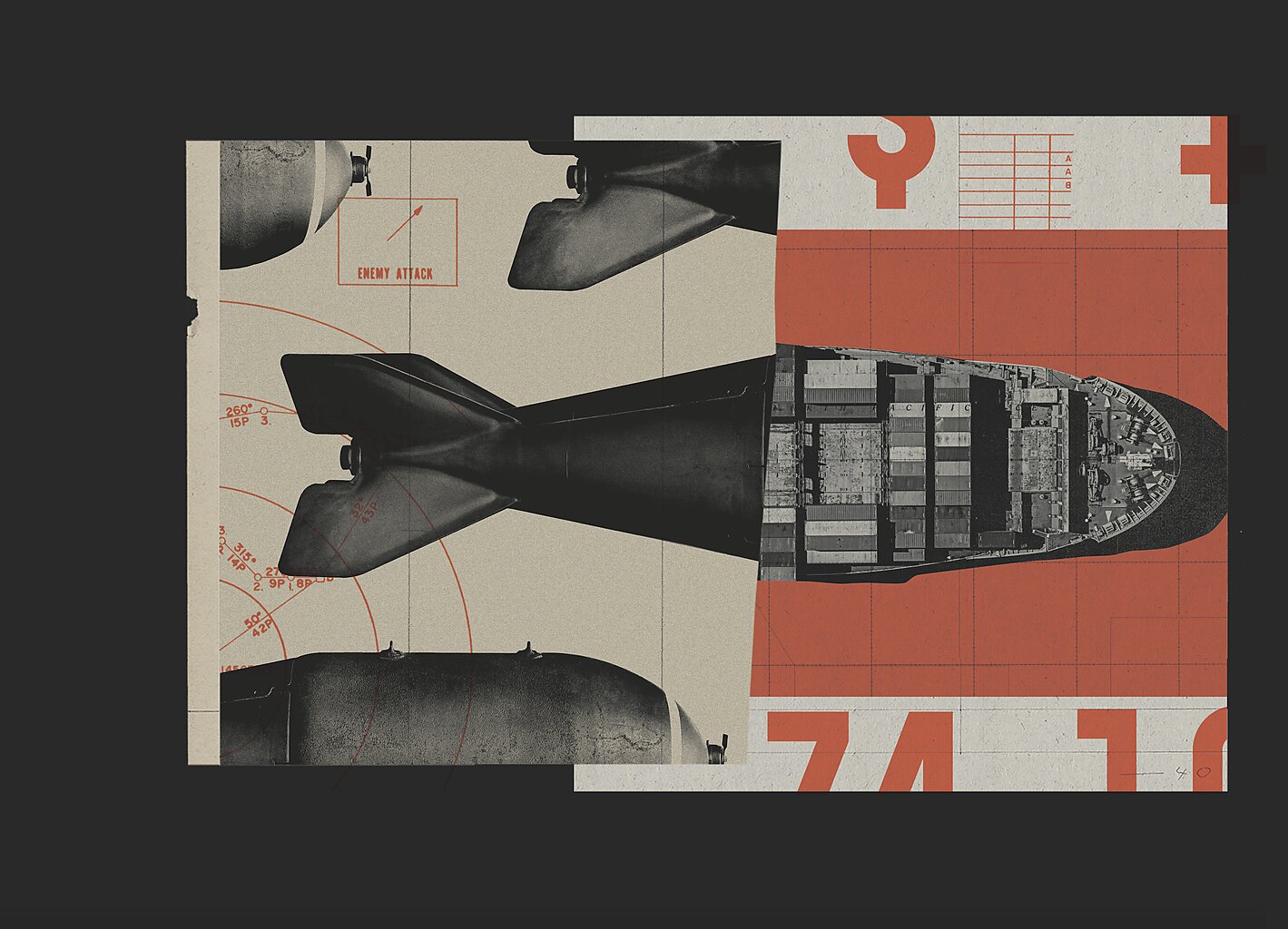

Illustrations by Mike McQuade

Liberty at Home, Restraint Abroad: A Realist Approach to Foreign Policy

The United States should embrace its unique geopolitical blessings and let realism and restraint guide American foreign policy.

ibertarians like economics more than politics. Economic exchange is voluntary, positive-sum, and creates wealth. What’s not to like? By contrast, politics is coercive, usually negative-sum, and destroys wealth (and potentially lives), spending on many causes that are unjust, don’t work, or both.

Whether or not we are interested in politics, politics is interested in us. The libertarian response to the constant expansion and encroachment of politics has been to try to push it back, working to reduce the number of conflicts settled at the political level; and for those conflicts that must be political, to devolve them to the lowest level of politics. The fascist political philosopher Carl Schmitt went so far as to argue that there is no liberal politics: “There exists a liberal policy of trade, church, and education, but absolutely no liberal politics, only a liberal critique of politics.”

Over the course of the 20th century, the tractor beam of the state has pulled an increasing number of issues under its control, to the point that today, contentious politics regularly erupt over issues such as which schoolchild uses which toilet. As ever, the incentive to deploy the state against one’s opponents is especially powerful for those who cannot win through persuasion.

And there’s no politics more political than international politics. States are animated by coercion. All states are illiberal to various degrees. International politics is a dog-eat-dog world where avarice, competition, hypocrisy, and death lurk in many dark corners. It’s about the most illiberal political arena one could imagine.

As one might expect, libertarianism has a number of things to say about international politics, but it is not a theory of international politics. Libertarianism, or “thin” libertarianism, anyway, is an austere theory of man’s relation to the state. It is no failing of libertarianism to admit that it isn’t a Swiss army knife: Libertarianism doesn’t contain a theory of international politics any more than it contains a definition of the good life and how to pursue it. For questions like these, a bounded theory like libertarianism needs help.

Below I outline two main arguments: First, that realism is a useful theory for libertarians—or anyone—to use in evaluating international politics. (That’s the “realism” part of the “realism and restraint” slogan you have hopefully heard in recent years.) Second, that since the Founding, geography—now combined with US economic and military power—makes most military dangers to the United States remote. Given US security, and given what libertarians know about the corrosive effects of war and security competition on liberal institutions at home, American libertarians should support realism and restraint in US foreign policy.

Illiberal Impulses in Foreign Affairs

In a brilliant and rollicking essay every libertarian should (re)read, Charles Tilly remarked that “banditry, piracy, gangland rivalry, policing, and war making all belong on the same continuum.” In Tilly’s most famous aphorism, “war made the state, and the state made war.” Preparing for war created government capacity, and governments with greater capacity tended to win their wars. The losers emulated the victors or died. War-making and government-building have gone hand in hand since the dawn of the nation-state.

War and security competition are sometimes necessary, but they are bad for liberty in any country, and they have been bad for liberty in the United States in particular. Foreign policy activism has disrupted the separation of powers, aggrandizing the executive branch at the expense of the legislature and judiciary. It has created enormous national bureaucracies and expanded government surveillance of US citizens. Participation in World War I brought the Espionage Act, the Palmer Raids, and an incumbent president throwing his opponent in prison for sedition on the grounds that he opposed the draft. World War II brought the country income-tax withholding, tens of thousands of American citizens in concentration camps for the crime of their heritage, and other monstrosities. War and security competition have over time helped replace republican institutions with oppressive bureaucracy, lawlessness, high taxes, regulations, and a general expansion of government power.

That is enough for many American libertarians to oppose most war and security competition, but it leaves open the question of when they ought to support war or other activist foreign policies. “What makes a state or other actor threatening to the United States, and what are the effective ways of dealing with such threats?” are important questions, but the answers cannot be found in works from F. A. Hayek or Richard Cobden or even Hugo Grotius. For their part, the American Founding Fathers had well-developed views about power. In an odd and underappreciated genealogy, they broadly fit within the tradition of political realism.

Realism is an unromantic view of politics. It views power as inherently dangerous, no matter who wields it. Unbalanced power in particular can produce reckless behavior. The Framers of the Constitution sought to separate power among the executive, legislative, and judicial branches not because they thought one or the other was inherently wicked but because they viewed unchecked power as inherently dangerous. As John Randolph put it, “You may cover whole skins of parchment with limitations, but power alone can limit power.”

This is an essentially realist insight. Power divided among self-interested actors produces the jealous defense of one’s own power, and therefore something resembling a balance, and a constraint on self-aggrandizement.

In the international realm, realists observe that international politics is a state of anarchy: There is no 911 a state can call to appeal to a higher authority to enforce constraints on state behavior. Norms are observed or violated as states see fit—and as they have the power to. To egregiously oversimplify, realists build on the assumptions of anarchy; of states seeking to survive as their highest goal; and of uncertainty about intentions, to evaluate international politics. (Here we could get into a thousand fine-grained infights among realists, but let’s not.) If public choice theory is “politics without romance,” international relations realism is international politics without romance.

The realist belief that the balance of power is the salient fact of international life—and the great power the salient unit—leads to a view that the United States should keep other great powers away from its borders (think of the Monroe Doctrine) and try to prevent any one state from dominating a region of the world that would allow it to grow strong enough to challenge the United States head-on. But unlike, say, Continental European states in the modern era, geography provides Americans a great natural advantage. Distance allows the United States to stay out of many great-power disputes. The Founders appreciated this, just as they understood the deleterious effects of activist foreign policies on domestic institutions. Distance, or “isolation,” if you prefer, was the crucial variable that allowed the United States to develop along a different path than that of Bismarck’s Prussia or Napoleon’s France.

America, “Blessed among the Nations”

From the time of the country’s Founding through the 20th century, American statesmen believed that geography was one of the United States’ greatest assets. In this view, geographic isolation allowed Americans a different kind of politics both internationally and at home. Great distance from threats of invasion made a form of radical republicanism possible in the United States, whereas perennial war and security competition made it unthinkable in Europe—particularly on the continent itself. In international politics, the United States could largely eschew standing armies and Continental-style bureaucracies, selectively tipping the balance if one part of the world looked in danger of being dominated by one state or another.

Looking back, it can be jarring to see just how powerful anti-militarism and faith in geographic bulwarks were in the early American republic. The Founding Fathers could make left-wing anti-war protesters sound like Dick Cheney. The admonitions of George Washington’s Farewell Address and even John Adams’s quip that “at present there is no more prospect of seeing a French army here than there is in Heaven” are well known. Less well known is the fact that concerns about the prospect of Congress possessing the power to “raise and support Armies” at all almost scuttled the approval of the US Constitution. As one member of the Massachusetts state ratifying convention fretted:

“A standing army! Was it not with this that Caesar passed the Rubicon, and laid prostrate the liberties of his country? … What occasion have we for standing armies? We fear no foe. If one should come upon us, we have a militia, which is our bulwark.”

One might object that the 18th century differs from the 21st in important ways, negating this view. We should recall, however, that European empires were still rampaging across the Western Hemisphere during this time, a much more proximate threat than whatever we may face today. Even after the English burned the White House to the ground during the War of 1812, American leaders still viewed geography as the nation’s most vital asset. As Abraham Lincoln memorably remarked in one of his earliest public addresses:

“We find ourselves in the peaceful possession, of the fairest portion of the earth, as regards extent of territory, fertility of soil, and salubrity of climate.… At what point shall we expect the approach of danger? By what means shall we fortify against it? Shall we expect some transatlantic military giant to step the Ocean, and crush us at a blow? Never! All the armies of Europe, Asia, and Africa combined … could not by force, take a drink from the Ohio, or make a track on the Blue Ridge, in a trial of a thousand years.”

Despite America’s dalliances with imperialism at the end of the 19th century, the view that geography protected the United States from most military dangers persisted well into the 20th century. In a statement attributed to Jean-Jules Jusserand, the French ambassador to the United States during the Great War, Americans occupied a most enviable position. The country was “blessed among the nations. On the north, she had a weak neighbor; on the south, another weak neighbor; on the east, fish, and on the west, fish.”

It was only after World War II that American policymakers worked to undo geography and make the United States into a continental power on other peoples’ continents. In particular, in the late 1940s and early 1950s, they saw Soviet power menacing the ruined countries of Europe and stepped into the breach. It was perhaps fanciful, but leaders like President Dwight D. Eisenhower hoped that the massive American military role would be ephemeral. In 1951, Eisenhower worried that “if in 10 years, all American troops stationed in Europe for national defense purposes have not been returned to the United States, then this whole project will have failed.” He could not have imagined just how badly it failed, though there are positive signs that the winds may be changing.

A Foreign Policy for an Insular, Maritime Republic

If you want to cause a lot of trouble in international politics, get control of a big, powerful state. Al Qaeda took a lucky shot in 2001 and killed 3,000 Americans. In response, Americans killed several hundred times more foreigners, almost none of whom had anything to do with the attack, without breaking much of a sweat. Some libertarians cheered on the most egregious parts of the campaign, like the Iraq invasion, as a smart “strategy of fomenting democratic regimes in the Middle East.” Predictably, though, it all came to ruin.

We remade huge chunks of the national security bureaucracy, which seem unlikely to ratchet back, and the War on Terror affected everything from air travel to pop culture. American families suffered needless deaths of thousands of American patriots and the grave wounding of tens of thousands more. Americans’ welfare suffered from the malinvestment of several trillion dollars into a fatally flawed ideological crusade. Other challenges, from US fiscal solvency to its position in Asia, took a back seat for decades. But the United States is so rich, so powerful, and so far removed from serious danger that even medium-sized mistakes like the Global War on Terror hardly break our stride.

The United States’ safety from danger allowed it to dream up the Global War on Terror. At the time of this writing, US aid has allowed Ukraine to survive its fight against Russian aggression, albeit with significant escalatory tail risk to Americans. The Biden administration protests that Ukraine’s fight is not Ukraine’s at all but rather part of some global struggle of democracy against autocracy. Early in the conflict, national security adviser Jake Sullivan declared that the United States had outsourced its diplomacy to Kyiv. According to Sullivan, “Our job is to support the Ukrainians. They’ll set the military objectives, the objectives at the bargaining table … we’re not going to define the outcome of this for them. That is up for them to define and us to support them in.” Kyiv has been defining, and Americans have been supporting, ever since. Some of us have protested that if our support was a necessary condition for Ukraine to stay in the fight, we should have a say regarding the ends to which our aid is put.

In contrast to feckless Russian commanders at Hostomel Airport and terrorists training on monkey bars, the challenge posed to the United States by China is serious. China is a big, powerful state. Its economy is now much larger relative to the US economy than the Soviet Union’s ever was. Its conventional and nuclear forces are both undergoing fundamental overhauls to make them leaner and meaner. Both the Trump and Biden administrations have been at pains to find ways to “decouple” the Chinese economy from sensitive sectors of the US and other Western economies, with varying degrees of success.

The promise that “if only we traded more with China, it would transform politically and come to peace with American dominance of Asia” has come to naught, at least so far. And while recent years have seen trade between China and the world in relative decline, it still provides the fuel for Chinese economic growth, which itself is the engine that produces Chinese military power. The questions of how and where to deal with China, and the question of who should do the bulk of the dealing, remain challenging. But the central features of international politics—states as the primary actors, the balance of power as the central question, and the rudely immovable fact of geography—endure.

If an invading army threatened to establish a lodgment in Florida or Oregon, most libertarians would swallow hard, support the effort to defeat them, and work to undo the government powers established by the crisis once it ended. But contemporary US conflicts are almost uniformly the product of ideological fever dreams. Most information about foreign threats comes to Americans directly from the bureaucrats tasked with defending against them. Libertarians should look on government’s national security claims with the same skeptical eye that they train on government’s economic analysis.