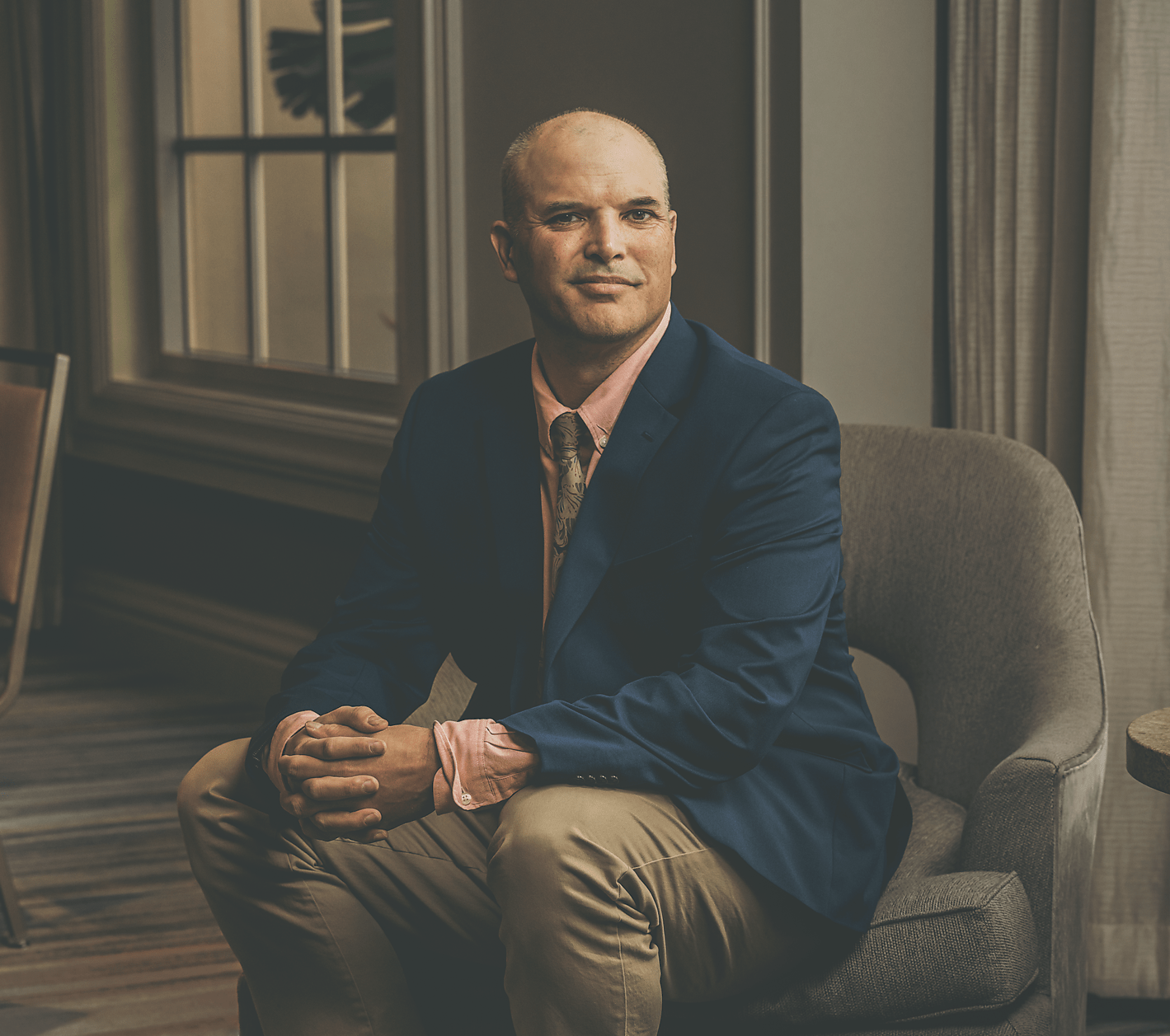

Photography by Greg Khan

“A Brand-New Belief System”: Matt Taibbi on How the Trump Era Changed Media’s Free Speech Stance

From the Twitter Files to unexpected IRS visits, investigative journalist Matt Taibbi warns of the precarious state of First Amendment rights.

ward-winning investigative journalist Matt Taibbi is worried that the media and the public don’t care about government surveillance or free speech like they used to. Formerly a contributing editor for Rolling Stone, Taibbi is the author of several books and currently writes for Racket News (formerly TK News) on Substack. In a conversation with Gene Healy, Cato’s senior vice president for policy, at a Cato event in Naples, Florida, this past February, Taibbi discussed government suppression of speech, the significance of First Amendment principles, and why a free press is needed to preserve our democracy.

Gene Healy: Tell us about the “Twitter Files”—how that started, what you found, and which aspects of it were most concerning.

Matt Taibbi: The reason that the new owner of Twitter [now known as X], Elon Musk, reached out to me and then subsequently a group of other independent journalists was, among other things, because he didn’t trust conventional media to report the story correctly. He very specifically picked out independent journalists, people who weren’t affiliated, at least anymore, with mainstream organizations. That included me—I had been at Rolling Stone—Bari Weiss, who had been at the New York Times … Elon wanted the public to know the extent to which platforms like Twitter were censoring their own customers.

I think his idea behind this, at least how it was expressed to me, is that he wanted to restore trust in the institution by sort of opening the kimono and letting the public know what was going on. But at that time, we only had a very distant idea that there might be some kind of government angle to this. At the very extreme end, we thought maybe there would be one or two letters from the FBI suggesting [to Twitter to] “stay away from this story or that story.” This is why we picked as our first subject the Hunter Biden laptop story, which we knew had been blocked by Twitter and Facebook, in what I thought was a historic moment for internet platforms in this country.

We didn’t find a whole lot from the FBI with that story, but then they allowed us to look kind of freely through some other files, particularly with regard to the 2020 election. And we started to see emails all over the place saying things like “flagged by DHS,” “flagged by FBI,” flagged by a whole variety of government agencies. We didn’t know what that meant, and it took about three weeks to a month for us to figure out that there was a very organized and extensive content-flagging operation where tens of thousands of social media posts had been picked out by various government organizations—in particular the FBI and the Department of Homeland Security—and they had been sent to companies like Twitter, along with about two dozen others, through a pretty formal system of content management.

Gene Healy, left, in conversation with Matt Taibbi at a Cato event in Naples, Florida.

That became the backbone of the story that we thought was significant because we had no idea that there was a big content moderation program going on with government. We subsequently found out that this was a huge fundraising issue as well. There was well over $100 million just from one agency involved in this kind of activity, so this was a very sizable program, and we were very fortunate to be able to uncover it.

Healy: And what kind of speech are we talking about? People who haven’t followed the story much must think, “First they came for Alex Jones, and I wasn’t crazy, so I did nothing.” But my understanding is that there was an effort during the COVID-19 pandemic to suppress some information that’s true from highly credible medical sources.

Taibbi: There were some things [they were flagging] that were obviously misinformation. The most common kind of communication that the FBI would complain about would be a social media post that would say something like “Democrats, don’t forget to go out and vote on Wednesday” in an attempt to make people forget to vote on Tuesday.

But then we started to find things that were clearly protected constitutional speech that they were recommending [for censorship]. They were saying, “We think this violates your terms of service” to things such as a video making fun of the Biden administration’s messaging on COVID-19.

And then we found things that were more nefarious than that. There were these private, cross-platform programs, some of them associated with big academic institutions, that talked openly about how we must consider suppressing true content that might promote vaccine hesitancy.

An example of that would be showing somebody who took the vaccine dying of myocarditis. That’s true, it happened, but [the FBI] doesn’t think it’s a good story. They had a term for this kind of content; they called it “malinformation.” Malinformation is something that’s true but produces an adverse result.

And this, we thought, was extremely dangerous because it was a way to get around the general journalistic idea, which is, “If it’s true, we print it.” It’s up to the public to figure out what to do with it.

Healy: How do you explain the tepid and even dismissive reaction to massive covert government efforts to suppress speech?

Taibbi: That’s a fascinating thing. In this new era since 2016, any issue that codes as a “Trump issue” is denounced and dismissed and set aside. I found myself sort of instantly recharacterized as a conservative, Trump-leaning journalist even though there’s nothing in my biography that suggests that. I wrote a book called Insane Clown President about Donald Trump.

But the Washington Post, in the days after the story broke, they described me as “conservative journalist Matt Taibbi” and then silently edited that within a few hours after people complained. There was a mysterious reaction from a lot of people in the press who should be concerned about this because it fundamentally affects them as much as anybody else. But they didn’t see it as a very dangerous issue.

If you go back to 1974, there was a big story in the New York Times by Seymour Hersh that came to be known as the “Family Jewels” story where he found out about this CIA program that was designed to engage in widespread illegal domestic surveillance. I asked him for advice about what to do about this story. It was a very similar thing because a lot of the agencies that were involved in this domestic censorship were expressly prohibited from doing so in America. A lot of them were foreign intelligence agencies or the State Department. And that story, too, engendered a lot of hostility from other people in the media who thought it went too far, that you shouldn’t write about this kind of thing because it can hurt important institutions in this country.

Healy: Speaking of the intelligence community and your recent reporting on efforts to surveil the Trump campaign, can you tell us a little bit about what you’ve uncovered there?

Taibbi: There have been a lot of reporters on both the left and the right over the course of the last six or seven years who’ve hinted at this. There was a House Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence nicknamed HPSI.

They had done an investigation in 2017 and 2018 into the origins of the scandal that came to be known as “Russiagate,” but only a portion of their research ever got out. That was the part about the misuse of [the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA)] and the misfiled warrant on the gentleman named Carter Page. But there was a lot of other stuff that never got out, and people who followed the story knew that there were other things that were out there.

That other shoe just didn’t fully drop until recently. It turns out there were at least 26 people around the Trump campaign who were placed under surveillance without legitimate predication well before the opening of the FBI investigation in the summer of 2016.

The other thing was that the intelligence community assessment of January 2017, which said that the Russians had conducted an influence campaign specifically to help Trump, that this was cooked intelligence. They had suppressed dissenting information, that, among other things, suggested the Russians were comfortable with Hillary Clinton. That [the Russians] felt she was manageable and reflected continuity.

My feeling on this, and we haven’t exactly been able to prove this yet, is that one of the reasons that this happens is not really Trump-specific. It’s just that there is widespread misuse of this Section 702 [of FISA] authority that unmasks which US persons have been monitored abroad.

And that’s very pertinent, I think, to Cato’s mission.

Healy: There’s a story from the fallout from the Twitter Files that, if I didn’t know it was true, I would think was crazy: an IRS agent showed up at your house the same day that you testified before the House Select Subcommittee on the Weaponization of the Federal Government back in March [of 2023]!

Taibbi: I got home that night and found out from my wife that there had been a note left on the door saying the IRS came and visited. “We’d like to talk to you, but don’t call us for four days.”

I thought, “This is too stupid to be related to any of my journalism work.” So, I did inform the committee that this had happened, but I didn’t say anything about it publicly because I didn’t want people to get the impression that I was being a conspiracy theorist.

It wasn’t until Jim Jordan’s committee got some answers back from the Treasury that I really started to get nervous, because it turned out that the case on me had been opened on Christmas Eve of 2022, which was a Saturday, and it was also the day of the biggest Twitter File story that was directly about the CIA, FBI, and the director of national intelligence.

That’s when I got nervous. It could still be a coincidence, but I lived in Russia for a long time. It struck a chord.

Healy: What do you think has happened to free speech culture and old-school nonpartisan civil libertarianism in this country?

Taibbi: I grew up in the ’70s, ’80s, and ’90s. Every culture-war story about speech was a litmus test issue for anybody who considered themselves a political liberal, which I was. I gave to the [American Civil Liberties Union] my whole life. Everything from The People vs. Larry Flynt to the Parents Music Resource Center to N.W.A. putting out its Straight Outta Compton album—you could not be politically liberal and be on the other side of those issues when I grew up.

Then when I went into the media, everybody was unanimous in believing in absolutely unfettered free speech. I had the good fortune to live overseas in Russia and see what happened when a country both acquired speech freedoms and lost them in a very short period.

That experience weighed on me very heavily and still does; how fragile it all is. And I think Americans once believed that very strongly. They were always very conscious of that in their history. But when Donald Trump came around, I think that’s when there was suddenly a brand-new belief system, particularly in the news media.

That’s one of the reasons that it’s been very difficult to get anybody in the regular press to do stories about censorship, surveillance, any of those things.