Illustration by Tyler Comrie

Blindfolded Juries, Coerced Convictions: Why Prosecutors Often Win Before Trials Even Begin

The Bill of Rights dedicates more words to the resolution of criminal charges than any other subject, establishing a criminal justice system in which defendants are afforded rigorous protections such as the presumption of innocence, the right to counsel, and trial by jury.

But the Founders would hardly recognize today’s adjudicative process, which is more akin to an industrial-scale assembly line that prioritizes expediency over fairness and churns out guilty pleas through ad hoc, extraconstitutional dealmaking that systematically excludes ordinary citizens from a process in which they were meant to be the key players. And the small handful of defendants who resist the often palpably coercive pressure to plead guilty will be tried by a jury that has been carefully curated and indoctrinated to ensure it is free of people who understand the historic powers of jurors in our system, including but not limited to conscientious acquittal.

S District Judge T. S. Ellis III sounded a regretful tone when he sentenced Frederick Turner to 40 years in prison on drug charges in 2018, explaining that he had “no discretion to change” the punishment due to a combination of mandatory minimums and stacked charges.

“The only thing I can do is express my displeasure,” Judge Ellis said. “I chafe a bit at that, but I follow the law.”

Prosecutors later indicated that they also had some buyer’s remorse, reportedly offering after the trial to support a reduced sentence if Turner waived his right to appeal and gave them information on other drug dealers.

But perhaps no one was as shocked by the four-decade sentence as the jurors who had recently convicted Turner on two counts related to dealing methamphetamine and two counts of possessing a firearm in furtherance of a drug-trafficking crime, wholly unaware of the draconian mandatory sentences that deprived the judge of any sentencing discretion.

“If anyone who sat in that trial said that person deserved 40 years, I’d question their judgment about everything in their life,” Paul St. Louis, a juror in the case, told Free Society. “The reality is: I didn’t have all the information, and if I did, I’m not sending that man to prison for 40 years. Just no way.”

Frederick Turner’s Descent

Turner, who spent much of his life grappling with addiction issues, was arrested in 2017 as part of Operation Tin Panda, a sweeping Justice Department crackdown on drug and gang activity in Northern Virginia. He had recently relocated to Virginia from his home state of Utah after a series of tragic deaths in his family, including both of his parents and his 25-year-old nephew, Cody Brotherson, a Utah police officer who was struck by a stolen vehicle and killed in 2016.

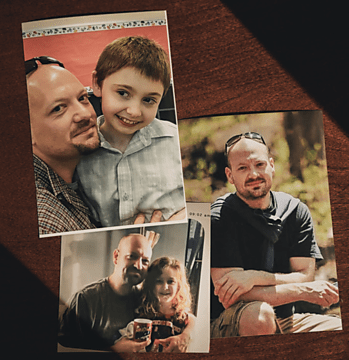

TOP: Frederick Turner pictured in family photos before his trial and incarceration.

LEFT: Mandy Richards holds a photo of her brother, Frederick Turner, whose 40-year prison sentence was questioned by one of the jurors who convicted him and even the judge who handed down the punishment.

PHOTOGRAPHY BY GREG KHAN

The turmoil of Turner’s personal life exacerbated his substance abuse problems as he searched for a fresh start. His spiraling addiction led him to a methamphetamine dealer named Bassam Ramadan, whom he began assisting in drug deals. Turner was never accused of carrying or using a gun, but firearms were present in Ramadan’s house, and Turner helped package a gun and meth together for one transaction with an undercover police officer.

“St. Louis’s reflections on Turner’s sentencing underscore the neutering of the modern American jury—groups of ordinary citizens who are kept in the dark about their true powers and duties so that they can act as unwitting rubber stamps for overzealous prosecutors.”

After Turner’s arrest, prosecutors stacked charges so that if he went to trial and was convicted, he’d face a statutory minimum of 40 years in prison—five years for the first firearm offense, 25 years for the second firearm offense, and 10 years for the drug crimes, all to be served consecutively.

As is invariably the case in federal prosecutions, the severity of this potential punishment was hidden from the jurors deciding Turner’s fate. Assistant US Attorney Carina Cuellar argued at the beginning of the trial that it would be “very unfair” to “play on the emotions of the jury” by telling them about the 40-year sentence Turner could face, according to a Washington Post report.

About three dozen other people were arrested as part of Operation Tin Panda, all of whom entered into plea bargains. Prosecutors offered Turner a deal that would have given him a 10-year sentence, but he refused, believing that the charges and the government’s narrative far overstated his actual culpability.

“He really believed that he could explain that he was very small, he was the only one with a first-time offense in the whole big picture,” Turner’s sister, Mandy Richards, told Free Society. “He truly was a small fish under this humongous operation. He thought he could tell his truth and the jury would understand it.”

Nullifying the Power to Nullify

The jury convicted Turner at trial, but the resulting sentence floored St. Louis, the juror who said he would have opted for jury nullification had the court been more transparent about the punishment Turner would receive if convicted.

“I did read after the trial—the Department of Justice announced Operation Tin Panda, and the press release says, ‘Look, we stopped this huge drug ring.’ If I had just read that, my knee-jerk reaction is, ‘Oh well, this is good, right?’ We’ve got guns off the streets. We have drug dealers off the streets,” St. Louis told Free Society. “But then you listen to the details in the trial, and what you find out is Rick Turner is a meth addict with mental illness, depression, and is selling drugs mostly to feed his own habit. And really what he needed was rehab—that was the solution to this.”

Paul St. Louis, one of the jurors who convicted Frederick Turner, said he would have opted for jury nullification if he had known the severity of the punishment Turner was facing.

Ramadan, the dealer whose house Turner had moved into, took a plea deal that landed him a 16-year sentence, less than half the time that Turner was ordered to spend behind bars.

Due to the length of his punishment, Turner was sent to a maximum-security prison in Colorado, where any hope he had left was extinguished. He wrote letters to his sisters and other members of his family, telling them that he was fearful for his life and too terrified to sleep.

Turner died in prison in June 2019, with the official cause of death ruled a suicide, though his family still questions that determination. For Richards, her brother’s four-decade sentence and transfer to a maximum-security facility were clearly a punishment for choosing to go to trial.

“I know he did drugs. I know he got involved with dealing drugs. I’m not naive to that, but he was broken, broken, broken, broken, and you put him in prison for 40 years because he didn’t take your plea. How wrong is that?” Richards said.

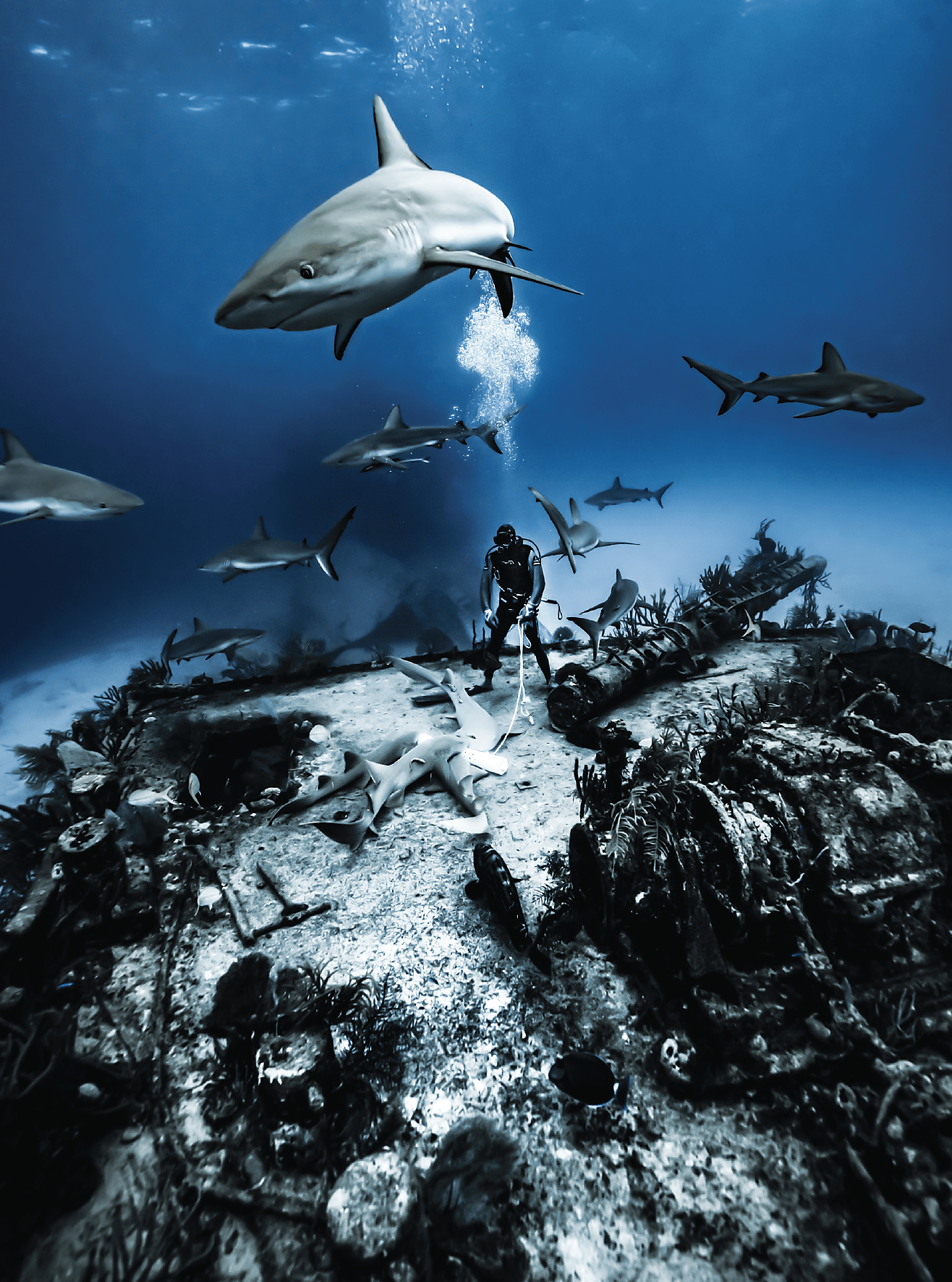

John Moore Jr. (above) and Tanner Mansell (left) were convicted and branded as felons for violating a “statute that no reasonable person would understand to prohibit the conduct they engaged in,” as it was put by one federal appeals judge.

St. Louis’s reflections on Turner’s sentencing underscore the neutering of the modern American jury—groups of ordinary citizens who are kept in the dark about their true powers and duties so that they can act as unwitting rubber stamps for overzealous prosecutors. Turner’s four-decade sentence seems less like a punishment for a crime and more like a warning to other defendants: Either take the plea deal or experience the terror of the trial penalty.

Soon after Turner was sentenced, Congress passed the First Step Act, which reformed mandatory minimums and would have resulted in a 20-year sentence in his case. It’s a move in the right direction, but mandatory minimum sentences are just one way that prosecutors exert pressure on defendants like Turner to waive their right to a jury trial and condemn themselves instead. This power imbalance is partly responsible for our current system of plea-driven mass adjudication that sees more than 95 percent of criminal convictions come from guilty pleas, with innocent defendants sometimes pleading guilty just to avoid savage trial penalties. This assembly-line style of McJustice has helped boost America’s incarceration rate to a point that is orders of magnitude higher than other liberal democracies around the world. And even with nearly two million people behind bars, actual violent crimes increasingly go unsolved. Police clearance rates for homicide stood at just 52.3 percent in 2022, down from 64.1 percent in 2013, according to a Pew Research analysis of FBI data. The clearance rates for aggravated assault, rape, and robbery have also declined at a similar pace and remain well below 50 percent.

Another aspect of our hypercarceral approach to criminal justice is prosecutors’ propensity to pursue convictions for trivial infractions that have nothing to do with public safety. A glaring example of this occurred in South Florida, where two members of a charter operation specializing in shark encounters were branded lifelong felons for an honest mistake.

Swimming with Sharks

John Moore Jr. and Tanner Mansell took a family out for a chartered snorkeling trip in the Jupiter Inlet near West Palm Beach in August 2020. After the first dive, they came across what they believed to be an illegal longline—a main fishing line with baited hooks weighed down to the seafloor by an anchor and connected to a buoy on the surface.

Believing the setup to be the work of poachers, Moore and Mansell took action, calling the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission (FWC) to report what they had found and then retrieving the line and cutting at least 19 sharks loose—all while encouraging their guests, including a vacationing Midwestern police chief, to record videos of what they were doing.

“Every action we took was with that mentality of uncovering a crime, uncovering an injustice, recording it, calling it in, then at the very end, John handing the line over to law enforcement officials,” Mansell, an experienced diver and underwater photographer who has worked on the Shark Week series for the Discovery Channel, told Free Society.

“But there is another side to the plea-bargaining coin that receives less attention, and that is the government’s remarkable success in transforming criminal juries from injustice preventing bodies into mere fact finders with no meaningful role in assessing the wisdom, fairness, or legitimacy of any given prosecution.”

Moore, a former commercial fisherman who grew up in a family with a charter boat business and who has spent his entire life on the water, was told by an FWC officer to leave the suspected poacher’s line at the dock.

“I never would have thought in a million years that we were doing something wrong,” Moore told Free Society. “We were out in this same area pretty much every day, five days a week, for years, and have never seen anything that resembled this.”

Their jubilation at freeing over a dozen sharks quickly soured the next morning, when commercial fishermen started criticizing their actions on social media. FWC officials inspected the line and discovered that it belonged to a fisherman who had a special permit from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration to conduct shark research.

Perhaps reflecting South Florida’s famous lack of actual crime, underworked federal prosecutors brought the case to a grand jury, which indicted Moore and Mansell on one felony count each of theft of property within the special maritime jurisdiction of the United States. The pair proceeded to trial in December 2022. Despite the looming specter of a felony conviction, they felt good about their chances of being found not guilty after all the evidence was presented.

“After the final words were said, we went back to the room, and we actually had a little celebration,” Mansell said. “All the information that we needed is out there. We gave each other hugs.”

But as jury deliberations extended from minutes to hours to days, the two divers felt more and more uneasy. Jurors sent out an incredible seven separate notes to the judge, asking for information about call logs, the defendants’ certifications and training, and the defense’s theory of the case.

On the second day of deliberations, a Friday, jurors sent a note informing the judge that the “jury [is] still very divided” and that “some people have to leave at 5.” The judge read them a so-called Allen charge to encourage them to break the deadlock. Just before leaving for the weekend—after two days of deliberations, longer than it took to present all of the evidence at trial—the jury returned a guilty verdict, branding Moore and Mansell lifelong felons.

They appealed their convictions to the 11th US Circuit Court of Appeals, arguing that the jury was given an inappropriately broad definition of the crucial word “steal” in the applicable statute. Moore and Mansell had asked the trial judge to advise the jury that “to ‘steal’” in this context meant “to wrongfully take good[s] or property belonging to someone else with intent to deprive the owner of the use or benefit permanently or temporarily and to convert [the property] to one’s own use or the use of another.” Prosecutors opposed the requested language about retaining the property for the defendants’ own use and the judge agreed, instructing the jury that it was irrelevant whether Moore and Mansell had taken the property for their own gain—which they plainly had not.

A three-judge panel of the 11th Circuit reluctantly affirmed the convictions, agreeing that there was no error in omitting the proposed language about self-benefit from the jury instructions—but not before taking the highly unusual step of chastising Assistant US Attorney Thomas Watts-FitzGerald by name for deciding to pursue felony charges in such a trivial case.

“John Moore, Jr., and Tanner Mansell are felons because they tried to save sharks from what they believed to be an illegal poaching operation. They are the only felons I have ever encountered, in eighteen years on the bench and three years as a federal prosecutor, who called law enforcement to report what they were seeing and what actions they were taking in real time,” Judge Barbara Lagoa wrote in a concurring opinion upholding the convictions.

“They are felons who derived no benefit, and in fact never sought to derive any benefit, from the conduct that now stands between them and exercising the fundamental rights from which they are disenfranchised. What’s more, they are felons for having violated a statute that no reasonable person would understand to prohibit the conduct they engaged in.”

Though the trial judge sentenced Moore and Mansell to one year of probation, sparing them the prison time that prosecutors had asked for, they have still been branded lifelong felons—with all the disabilities and stigma that label carries with it—for a well-intentioned mistake.

“It’s still so strange to hear anything on the radio or TV, ‘This person was convicted,’ and the first thing that pops into my head every single time is, ‘I wonder if they were innocent,’” Moore said. “It skews your whole view of the criminal justice system.”

Recentering the Independent Jury

The Founders knew very well that the ability to prosecute and punish citizens is the power most frequently—and easily—abused by oppressive governments. So, it would likely come as no surprise to them that stories like the ones described above could happen. What would almost certainly shock and dismay them, however, is not just that those miscarriages of justice did happen, but how they happened.

Our system was painstakingly designed to avoid injustices like the ones inflicted upon Turner, Moore, and Mansell. But the system we have today bears scant resemblance to the one so carefully set forth in the Bill of Rights, which dedicates more words to the process for adjudicating criminal charges than any other. Bar none, the biggest difference between the criminal justice system conceived by the Constitution and the actual one today that makes America the top incarcerator of human beings in the developed world is the role—or lack thereof—played by ordinary citizens in the process of criminal adjudication and punishment.

The system described and prescribed by the Constitution puts regular people at the very heart of the administration of criminal justice. Thus, before the government may brand someone a criminal and sentence them to prison, it must persuade 12 community members sitting as a jury that the defendant is guilty of the charged crime and deserves whatever punishment prosecutors seek. At least, that’s how it works on paper.

The reality, unfortunately, is much different. In today’s system, ordinary citizens have virtually no say in who gets convicted or how they get punished. That’s because the vast majority of criminal cases end in guilty pleas, whereby defendants condemn themselves by waiving their right to a public and adversarial jury trial at which the government must prove a defendant’s guilt beyond a reasonable doubt to the satisfaction of a unanimous jury. What on earth would persuade nearly everyone who gets prosecuted in our system to exchange the possibility of acquittal and freedom—especially in a system bristling with defendant-favoring procedural protections—for the certainty of conviction and punishment? The answer is pressure, and lots of it.

The Supreme Court has recognized that ours is no longer a system of trials as conceived by the Founders but a system of ad hoc, extraconstitutional plea bargaining—and one, it should be added, that sacrifices the constitutional values of transparency, fairness, and due process on the altar of efficiency.

Cato scholars have thoroughly documented the many coercive levers available to prosecutors to induce guilty pleas, including threatening defendants with draconian mandatory minimum sentences (some of which prosecutors themselves lobbied for precisely to increase their own plea leverage) or even the death penalty; creatively stacking charges to increase sentencing exposure; gratuitous pretrial detention; and even threatening to indict a defendant’s family members if he insists on going to trial.

But there is another side to the plea-bargaining coin that receives less attention, and that is the government’s remarkable success in transforming criminal juries from the injustice-preventing bodies they were meant to be into mere fact finders with no meaningful role in assessing the wisdom, fairness, or legitimacy of any given prosecution. As the venerable constitutional scholar Akhil Amar has observed: “The present-day jury is only a shadow of its former self.”

Tanner Mansell and John Moore Jr. have decades of experience between them on the waterbut had never seen a legal longline fishing setup like the one they encountered in August 2020.

The government accomplished this radical transformation of the criminal jury by carefully indoctrinating potential jurors with a false narrative about their role in the process. Simply put, judges, prosecutors, and other system actors strongly suggest to jurors—and in some cases even falsely represent to them—that they lack the power to follow their own consciences when deciding whether to acquit or convict a given defendant. Jurors are often told during orientation that their only role is to determine the facts of the case and then mechanically apply the law, given to them by the judge, to those facts in order to arrive at a verdict. They may even be asked whether they are familiar with the concept of “jury nullification” and dismissed from the process of jury selection if they evince support for the concept.

Cato is working on two powerful reforms to disrupt plea-driven mass adjudication and return constitutionally prescribed jury trials to their proper role as the default mechanism for resolving criminal charges in America. The first would require support from legislators, judges, and other policymakers; the second and perhaps more ambitious one would be imposed on the system against its will.

A cornerstone of the perceived legitimacy of plea bargaining, which is nowhere mentioned or approved in the Constitution and was unknown at the time of the Founding, is the perception among system actors that it is nearly infallible—in other words, that it is virtually impossible to induce an innocent person to confess to a crime they did not commit, and therefore we need not be particularly concerned about the lack of any judicially administrable standard for distinguishing between voluntary and coerced guilty pleas. And while there is abundant anecdotal evidence that this confidence is misplaced—for instance, some 15 percent of the nearly 4,000 people on the National Registry of Exonerations were convicted based on false guilty pleas—no one has managed to quantify precisely just how reliable plea bargaining really is. But there’s a remarkably straightforward way to do that: the trial lottery.

As suggested by professors Kiel Brennan-Marquez, Darryl Brown, and Stephen Henderson, one way to audit the plea process would be to take a random selection of cases in which a plea has been reached but not yet entered and send them to trial to see whether the government is able to secure a conviction. If so, the defendant (who had nothing to do with the case going to trial) receives the benefit of the agreed-upon plea; if acquitted, the defendant walks; and if there is no unanimous verdict, the case may either be retried or resolved by plea. As with any revolutionary proposal, there remain details to work out and challenges to resolve, but given that there is not a constitutional right to plead guilty and all the proposal really entails is making greater use of the constitutionally prescribed mechanism for resolving criminal charges, there is no insoluble legal or practical obstacle to running this experiment—the results of which would reveal, with much greater precision, just how reliable or unreliable plea bargaining really is.

The second reform Cato is working on—the one that can be imposed upon the system without the support of judges, legislators, or other policymakers—is a juror-education campaign designed to familiarize people with the concept of jury independence (which includes but is not limited to so-called jury nullification) and make it impossible to empanel juries that are entirely free of people who understand the true historic, injustice-preventing role of criminal jurors in our system. The centerpiece of the campaign will be a vivid, emotionally engaging, and compelling video about how our painstakingly designed adjudicative process has been transformed into little more than a conviction machine to support a self-defeating and inhumane policy of mass incarceration. Unlike the indoctrination that jurors and potential jurors receive from the court system, Cato will encourage its audience to do their own research and form their own conclusions about the true role of criminal juries in our systems of government and justice—and to be guided by their own convictions about their proper role as citizen-jurors instead of having that role dictated to them by representatives of the government.

The prospect of going to trial before such a “Founding-era-informed” jury would likely influence not only the decisions of some defendants about whether to accept a plea offer but also the substance of those offers by prosecutors and their decisions about which cases are worth pursuing. Just think how different Moore’s and Mansell’s lives might be today if they could have gone to trial before a jury that was given complete information about its true powers and prerogatives, including the ability to acquit against the evidence to prevent injustice.

Criminal law has a vital role to play in our society by deterring and punishing harmful conduct that threatens the very fabric of civil society. But a criminal justice system can function properly only when it earns and enjoys the confidence of the citizenry it serves. A system that routinely cuts corners, flouts constitutional guarantees of due process, coerces guilty pleas, and systematically misleads citizen-jurors about their true role in the adjudicative process does not merit the trust, support, or confidence of the public. Fortunately, we can change that—and we will.