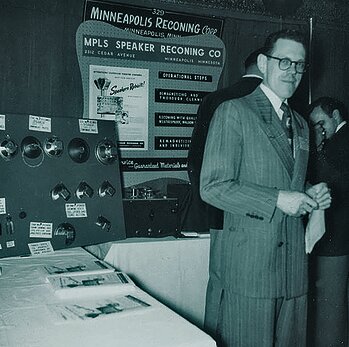

Digre had been struggling without success to find someone to repair his wife’s broken radio, eventually deciding to just recone the malfunctioning speaker himself with the help of some classmates at radio school. That experience led Digre to create the Minneapolis Speaker Reconing Company in 1949, repairing everything from radios to speakers for drive-in movie theaters. The start-up transitioned to creating original speakers in 1956 and evolved into MISCO (Minneapolis Speaker Company), with Digre and his partners honing the full manufacturing process over the next three decades, including design, production, and testing.

Dan Digre, Clifford’s son, took the helm in 1990 and grew MISCO into a respected original equipment manufacturer, creating custom speakers for commercial aircraft, vehicles, medical devices, instruments, and even the Orion spacecraft for NASA’s Artemis mission.

“MISCO has changed quite a bit in response to changing markets, changing technology,” Digre told Free Society while reflecting on the company’s 75-year history.

Adjusting to market forces and customers’ preferences allowed MISCO to continue growing in the United States while other manufacturers shipped production overseas.

In 2018, though, MISCO’s costs skyrocketed 25 percent overnight—not because of a supplier’s bankruptcy or the cancellation of a big contract, but because of hundreds of billions in new tariffs that former president Donald Trump placed on goods from China.

“If we’re going to build speakers in America, we’ve got to buy these low-cost inputs, raw components, which are no longer made in America, and get them from wherever we can in the world,” Digre said.