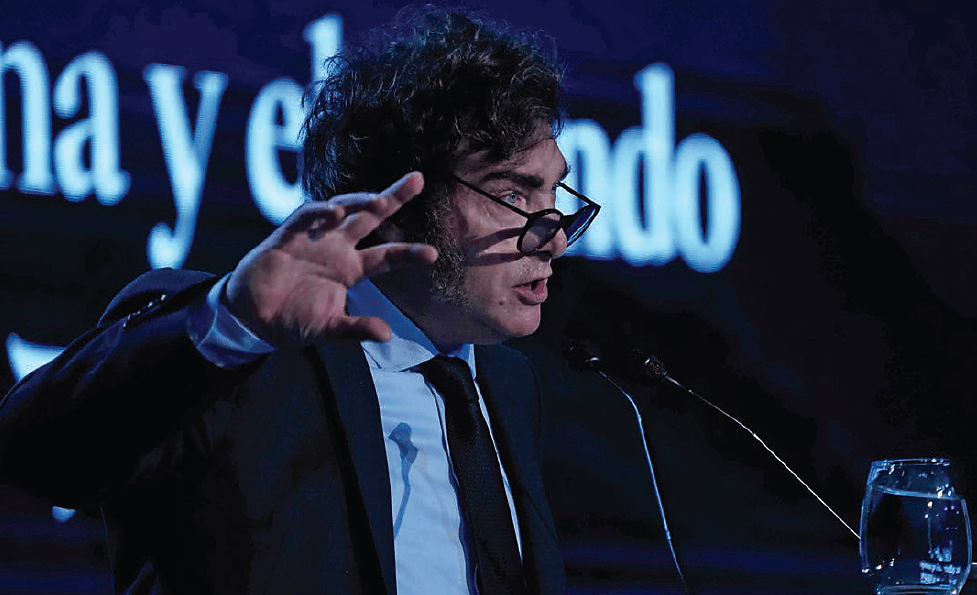

“Either we persist on the path of decadence, or we dare to travel the path of freedom,” Milei declared at the “Rebirth of Liberty in Argentina and Beyond” conference in June. “If we manage to make way for freedom, if we manage to remove the state enough for society to flourish, we will have succeeded because free economic activity will lead to benefits for all of society. If we achieve this, it won’t be a triumph of ours, but of society as a whole, which will have left behind 100 years of statism.”

An economist by profession, Milei was elected president last year on the promise of ending inflation, slashing his country’s bloated bureaucracy, and replacing Argentina’s corporatist state with a liberal democracy. But his rapid rise did not happen by chance. Classical liberal thinkers have been laying the groundwork for decades, and Milei credits libertarian scholars as powerful influences. That includes prominent Argentine economist Alberto Benegas Lynch Jr., a Cato adjunct scholar whom he cites as his intellectual mentor.