This interview with Harrison Moar, vice president for development at Cato, was one of David’s final interviews. He called on all of us to defend liberty in these turbulent times while giving us hope that we can better this world for future generations, just as he had in his lifetime.

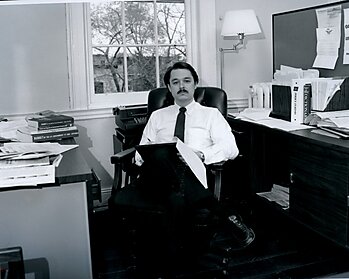

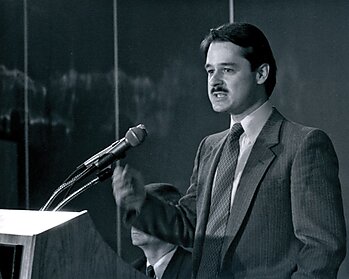

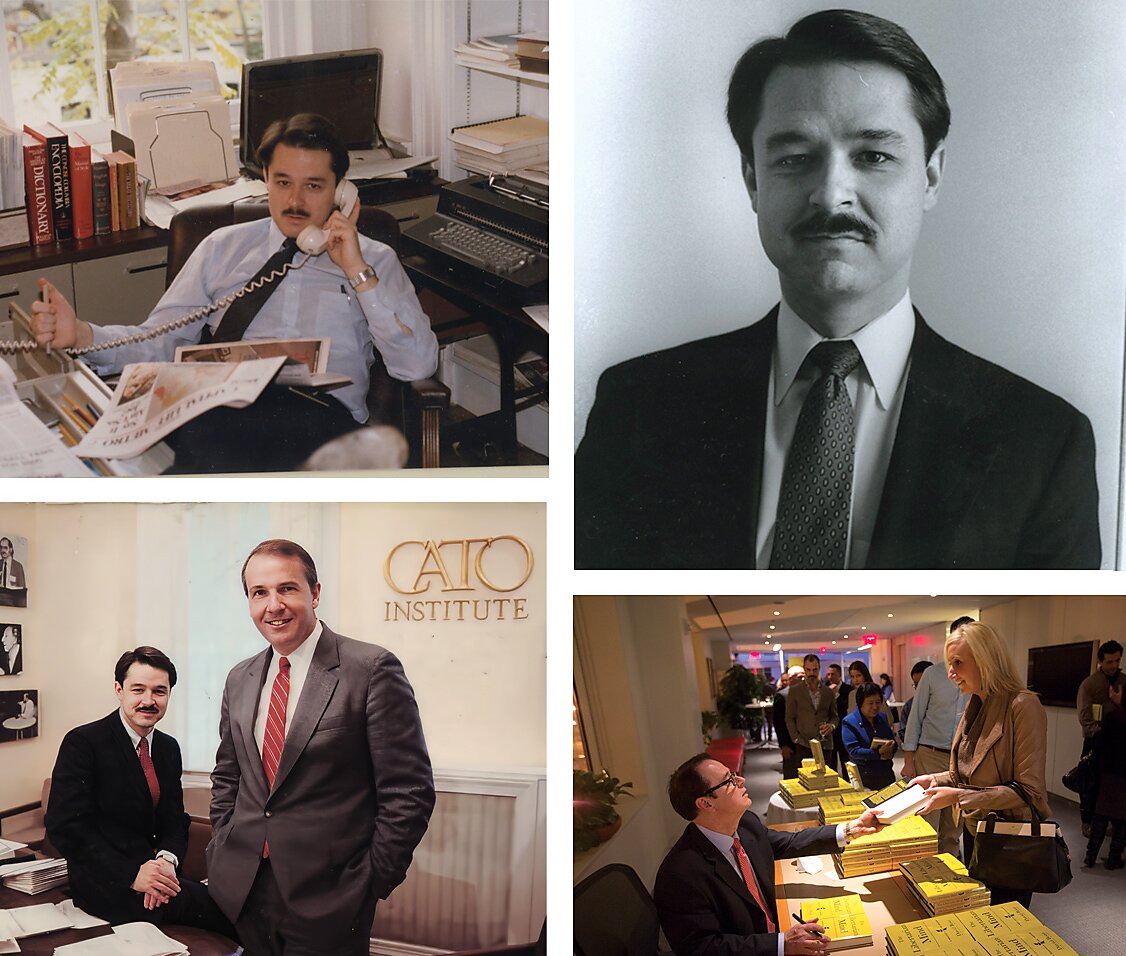

or more than four decades David served as the Cato Institute’s vice president for public policy and executive vice president, playing an indispensable role in the development of Cato and serving as a foundational figure of modern libertarian thought. The New York Times, Washington Post, National Review, Reason, and other media outlets released obituaries that noted the significant role he played in mainstreaming libertarian ideas, with the Post observing that “Mr. Boaz helped shape the course of libertarian thought from his longtime intellectual home at the Cato Institute, which he joined in 1981.”

“Keep Cato Cato”

Harrison: There’s little doubt in my mind that your life has been one of critical significance for the survival and advancement of libertarian principles. What in your career are you most proud of?

David: I’m most proud of the 40 years I put into building Cato, building what I think is the most important libertarian institution in the world. Ed Crane had the vision; he created it and raised the money. Charles Koch initially contributed the money that made it happen. But I was carrying out Ed’s vision and mission day to day with every paper we did, and with every conference we did.

Harrison: David, you’re known for a few things around the building, but two that stick out are your ability to spot a typo in a footnote from 50 yards away and your desire and long-standing reputation for keeping Cato Cato. I’d like to hear you talk about what that means to you and why that’s been important.

David: Let’s focus on keeping Cato Cato. We were created to provide an alternative voice in Washington and the national dialogue. Not liberal, not conservative—libertarian. The ideas of the American Revolution. We were going to be independent of other organizations and financial sources. We weren’t going to take government money, and we weren’t going to be the private project of some foundation or individual.

Ed Crane used to say that the thing he did for libertarianism was put libertarians in suits and ties—because there had been a lot of libertarians not in suits and ties before that! But that also meant we were going to publish books that were well researched, well edited, and well footnoted. We were going to make those books look like a book you would see in a bookstore, not like a think-tank pamphlet. Mainstream presentation of radical ideas was one of the things we always thought about.

Harrison: Why do ideas matter today? Why do they matter at all?

David: Ideas matter because they change the world. Deirdre McCloskey talks about what caused liberalism, what caused per capita income in Europe to rise suddenly after 5,000 years of stagnation. It wasn’t just that they invented double-entry bookkeeping. It wasn’t that they invented a sewing machine. It was, she says, the fact that people’s ideas changed, people’s attitude toward business and enterprise and progress, and just the idea that you could better yourself. The ideas of liberty that changed the world—running particularly from John Locke to the American Founders to the abolitionists—were just revolutionary.

Harrison: Have you always viewed the Cato Institute as the vanguard of these ideas?

David: We’ve always been very cautious at Cato not to say “We’re the best.” But I believe that it is Cato’s role to try to be a leading exponent of libertarianism. That’s our goal. That’s what we shoot for and aspire to.

Harrison: How important have nonpartisanship, credibility, and independence been, and how have we maintained steadfast adherence to those?

David: When we hired more employees who hadn’t been there at the beginning, we told them Cato is an independent, nonpartisan, libertarian think tank, and each of those three parts is important.

We are independent of other influences; we are nonpartisan, which is easy enough—looking at Democrats and Republicans, it’s easy to stay away from both of them! We are libertarian—that’s built into our DNA. And we are a think tank. We’re not a lobby. We’re not a student organization. We’re not a political campaign. All those things are valuable, but that’s not what we are. And what that comes to, I think, is making Cato, in my view, the most important source of libertarian policy analysis in the world. And now we are recognized as such because think tanks around the world take their cue from Cato.

Music provided by Chillhop Music

“The Movement Has Gotten Much Bigger”

Harrison: Let’s go back to the founding of the Cato Institute, in 1977, or at least when we moved to Washington, DC, which would have been 1981.

David: We didn’t get into our building (thanks to governmental obstacles) until early 1982. For a few months, we were a tiny band of entrepreneurs in a one-bedroom apartment on Capitol Hill. We would all be out in the main room doing our typing or phone calls, and if you needed to have a private conversation, like with a job applicant, you had to go to the bedroom!

If you think about what the world was like in 1977, the communists controlled a third of the world. And there was always a Democratic Congress. Keynesianism and related ideas were still in total control. Milton Friedman was an outlier. There were just three television networks. So I think there’s been a lot of change, mostly in a good direction. Since then, communism has fallen, at least in Europe. When I was a very young man, I was worried about being drafted and sent to Vietnam.

Harrison: What was the thinking behind moving Cato to Washington, DC?

David: Milton Friedman said, if you go to Washington, you will get corrupted. It’s certainly something to worry about and watch for. Ed Crane didn’t want to live in Washington at first. He wanted to live in California. But after being there for a while, he came to believe—and persuaded the board—that policy discussion took place in Washington, especially then with no mass media, no social media or internet. If you wanted to be part of that dialogue, you needed to be there. And I think we found that was true.

In Washington, many of the people in the crowd at events are journalists, policymakers, and certainly many congressional staffers, as well as people who work at other think tanks. The American Enterprise Institute, Brookings, and Heritage were all in Washington at the time.

Harrison: Moving on through the 1980s, Cato’s reputation and the staff were growing, and we decided that it was time to start reaching people in authoritarian regimes such as the Soviet Union and China. Cato was involved in distributing publications and holding conferences. How important do you think those efforts were in introducing liberal ideas into those countries?

David: Libertarians and economists had said for decades that communism doesn’t work, that it can’t last. But for decades, it seemed like it was lasting. Then, there were moments when you thought maybe something was starting to change, such as in Hungary and Poland in the 1980s.

We believe that ideas have consequences. And if you don’t make these ideas available, then they won’t be able to have any impact.

A college student sent Milton Friedman Russian translations of some of his articles that she had done as part of her Russian class—he didn’t read Russian much, but Friedman sent them to Ed Crane, and he said, “Well, why don’t we try? Why don’t we turn these into a book and see if we can get some books into Russia?” So that was one of the things that happened. Another big motivating factor was the Solidarity movement [challenging the communist regime] in Poland, which inspired us to create a book of libertarian essays focused on Poland.

Harrison: If people don’t see other institutions putting these ideas out and normalizing them, then they’re going to be scared to step forward themselves. I think the community Cato has built over the years with its friends, partners, supporters, and others really created an impact. And I hope the same was true for those we reached in the Soviet Union.

David: Yes, I’m sure that’s true. There had been dissidents in the Soviet Union who smuggled free-market publications in, including ours, and did so at great risk to themselves. Community matters. The more people who stand up for something, the more they’re going to have an impact.

It did seem that the end of the Soviet Union came very fast. In many cases, the Soviet bloc nations promptly threw out their own Communist Party. But they didn’t have any plans to get to a functioning market economy. It was done better in some places and worse in others. Cato people got involved in writing those plans and holding conferences in some of those countries.

Harrison: It wasn’t always the case that you might see the “libertarian Cato Institute” quoted on the front page of the Wall Street Journal. What has been the key to making that happen and ensuring that the ideas are spread more widely and taken seriously among the media?

David: I can remember going to events in Washington, and just because somebody recognized me, a speaker would say, “Now, I know the Cato Institute isn’t going to go along with this, but,” or “I wouldn’t go as far as David would, but.”

It was an indication that they recognized that there was a libertarian point of view, a libertarian constituency of some sort in the country, and we were the focus of it for a long time. There are a lot of other organizations doing that now, and many of them were founded because of Cato’s model.

The movement, the number of people, the number of books and everything has gotten much bigger. In 1974, F. A. Hayek won the Nobel Prize. In 1975, Robert Nozick won the National Book Award. In 1976, Milton Friedman won the Nobel Prize. And I was just finishing college at that time.

This was stunning each time to us. There’d never been anybody like Hayek getting the Nobel Prize—and then Friedman two years later! But since then, there have been a lot of basically libertarian economists who have won the Nobel Prize. Not as prominent generally as Hayek and Friedman, but working in the same field of study. I think those things have put libertarianism on the map. And Cato was at the center of a lot of that.

Another thing we did early on was talk about principled judicial activism. We rejected the idea that the courts should never overturn any laws and rejected the idea that the courts should just do whatever the Harvard faculty thought seemed like a good idea. The Supreme Court should enforce the Constitution! And when the government does something that exceeds its powers under the Constitution, the Court should strike it down. We’ve hosted debates, forums, luncheons, and other events for scholars and law students to change the landscape.

Harrison: You’ve written thousands of pieces and edited thousands more, as well as countless books and studies. Which of those are you most proud of, and which do you think has been the most influential?

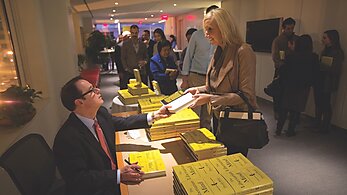

David: I’m most proud of The Libertarian Mind, which was originally Libertarianism: A Primer. That’s my crowning accomplishment. For Cato generally, there have been hundreds of books and thousands of articles, so it’s hard to remember which ones stand out the most.

Our first hardcover book, Social Security: The Inherent Contradiction, was influential on our program for the next 20 years. It introduced the idea that everybody knows Social Security is headed for bankruptcy, and the solution is allowing people to privatize their Social Security contributions. We popularized that idea with conferences and other books. We found that José Piñera had done that in Chile. So, we brought him up here and he gave lots of lectures, including a dinner with Ed Crane and George W. Bush while he was governor. A few years later, Bush campaigned to change Social Security and set up a commission to do that.

Another book we did early on was called Beyond Liberal and Conservative. It was written by two political scientists, and it said liberal and conservative aren’t the only choices. If you think there are two kinds of issues, like social issues and economic issues, then there’s a four-way matrix, with libertarian being one of those boxes. That got a lot of attention. It got pundits and political operatives thinking in that way. Again, we followed it up with conferences and seminars and policy papers.

Patient Power was our book that offered a privatization alternative to what ended up being Hillary Care. The book became something people waved when they went to rallies against Hillary Care, and Hillary Care was stopped. We didn’t stop at a 700-page book. We did a 120-page version and printed 300,000 copies of that. Then we did a 20-page version. It was a full-court press for discussing these ideas.

And then there was a book called Global Tax Revolution. One of the people we know who read it was Paul Ryan, who was a junior congressman at the time. About 10 years later, Paul Ryan led the 2017 tax cuts. Now, it wasn’t the only book on taxes that Paul Ryan ever read. But we do know he read that one, and some of those ideas found their way into the 2017 tax cuts.

Harrison: We’ve distributed over seven million copies of our pocket Constitution. Tell me about that!

David: Tom Palmer had the idea that Americans love the Constitution, even if they don’t know much about it. Presentation matters. We wanted something you’d be proud to hand a friend. So, we started distributing that, and we got little blurbs in newspapers saying it existed. It wasn’t the only pocket Constitution in existence, but it was the best looking.

We wanted people to recognize that the first thing the Constitution does is set up a government that limits power and asks of any proposed government policy whether it is authorized by the Constitution.

“A Culture of Tolerance and Free Speech”

Harrison: Are there freedoms today we take for granted?

David: In the United States and Europe and much of the world, we are not subject to the arbitrary rule of an autocrat, whether that’s a priest or a king or a satrap or a sultan. It’s also true, of course, that we have more free speech, we have more freedom of religion. We don’t notice these because fish don’t notice water. We live in a largely liberal free society because of the efforts of liberals who went before us. We’ve mostly eliminated slavery in the world.

Then you can just get into more technical things like free trade. It’s what makes possible much of our prosperity and abundance. But we mostly don’t think about it. You go to the grocery store, and you can buy kiwis from New Zealand.

Harrison: One of the things Cato’s cofounder Ed Crane would emphasize is the dignity of the individual and the importance of tolerance, and how that separates us from collectivists. Why are tolerance and pluralism important for a free society?

David: If there’s a lot of intolerance in society, there’s unlikely to be a lot of freedom. People who look down on others as a class, who think that some classes are just not as good as others, are likely to favor government help for the “right” people, and government restrictions for the “wrong” people.

We want to live in a culture of tolerance and free speech, not just a legal regime of free speech. It’s better to live in a liberal society that treats everyone decently, where individuals treat everyone decently.

Harrison: You’ve recently written about a new politically homeless grouping in America, the classical liberal center. Who are these people? What do they believe, and how can we, the Cato Institute, reach them?

David: Many of them don’t realize they’re homeless.

I’ve always said I’d like to be part of a libertarian vanguard of a liberal party or movement. Somewhere along the way, basically about 1900, in the Progressive Era, the liberals who believed in free markets and small constitutional government and the liberals who believed in liberating people who had been excluded took divergent paths, but they should have stayed together. We would have had a liberal majority.

One concern is that people began to take these freedoms and prosperity for granted, and they forgot that you have to work at it. They thought we could just tax a little, and then a little more, and “help” the corporate farmers, single mothers, children, and so on with all manner of programs. And that’s how you get a very big government.

What can we do about it? Some electoral reforms, like ranked-choice voting, might help. One of the things our current political system is doing is creating polarization because each party gerrymanders, and then you end up with people whose only concern is winning the primary. That problem pushes us in that direction. A fair number of libertarians are thinking about this sort of thing right now.

“We Wouldn’t Be Here If It Weren’t for Cato’s Supporters”

Harrison: Were your original goals in building the Cato Institute realized?

David: I think so! We would never have dreamed in 1977 or even 1982, when I was joining Cato, that we would be this big or this influential. Of course, many people would say, “But you would never have dreamed that government would be as big as it is after your 40 years.” That’s true. Every time I speak to donors, they ask what we’re going to do about entitlements, spending, and the national debt.

Harrison: David, tell me about the importance of Cato’s supporters.

David: Obviously, they’re crucial. We wouldn’t be here if it weren’t for Cato’s supporters. Now we’ve got more than 10,000 active supporters each year, so we can be much bigger, and we can do lots of things. We built our building, and then we expanded it. We’ve held conferences in Russia, China, and Mexico, and now we’re just about to hold one in Argentina, focused on the Milei agenda. We couldn’t do any of that without the support of our Sponsors, especially because we don’t take government money. We don’t have one big foundation funding us. We have a lot of people, and we appreciate it. They know that we don’t do things because they ask. They support our work because they like our work.

Harrison: Is there anything that makes our supporter community unique?

David: I think even though a lot of them are very affluent, they seem very down to earth. I find they’re not focused on what policies would benefit them. They’re focused on what policies would fit within what they understand to be the constitutional limits of government and whether a decision is prudent relating to markets, private property, and individual freedom generally.

“My Charge to Young People”

Harrison: After young people start with your books, what thinkers or books should they look to?

David: I started with Economics in One Lesson by Henry Hazlitt. Ten or 15 years ago, I thought we should update it, so I contacted a good contemporary economist and asked how he would like to update it. But then I read it again, and I realized it doesn’t need any updating!

Another book on economics that I really like to recommend to people is Eat the Rich by P. J. O’Rourke, which asks the fundamental question about economics: Why do some places thrive and others just suck? He goes to different places, some that thrive, some that don’t, and draws lessons in a fun way. He’s a funny writer.

And like anybody else, I would recommend The Road to Serfdom by F. A. Hayek, On Liberty by John Stuart Mill, and the writings of the Framers of the Constitution.

Harrison: What is your advice for the next generation of Cato leaders?

David: I spoke to Students for Liberty recently. One of the things I said was that in the 1940s, the world looked really bad. In the 1930s, you had the rise of communism and Nazism and fascism, and then you had a great world war. And in the middle of this world war, while fascism and communism were still in place, and we’re getting the Rooseveltian welfare state in this country, three remarkable women rose: Ayn Rand, Isabel Paterson, and Rose Wilder Lane.

They wrote books that lit a fire that took a long time to grow, but they challenged the collectivism of all these ideas and defended traditional American individualism. And of course, around that time Hayek wrote The Road to Serfdom. They started a counterrevolution against communism, to some extent, but also [against] the welfare state and collectivism in America.

Then in the 1970s, when Cato was getting started, there was a big Keynesian welfare state in the United States and other places, and people who had read these books started organizing, talking, and pushing back against those things, particularly resulting in the Reagan and Thatcher administrations. They weren’t right about everything and didn’t accomplish everything they said they would, but they revived a spirit of entrepreneurship and progress. I believe that Reagan’s marginal tax rate cuts significantly affected what became the long boom.

My charge to young people is this: Now we have illiberalism rising on both left and right in the United States and around the world. Illiberalism is challenging the whole idea that we should be a free and individualistic society and that that’s what creates the incredible prosperity we have achieved.

As young people, it’s your job to pick up the torch that Ayn Rand, Isabel Paterson, and Rose Wilder Lane picked up and passed on to people like Milton Friedman and other free-market scholars. You need to be fighting back against the illiberalism in the United States, and the worst illiberalism around the world, not just in Russia and China, but in places like Mexico, Turkey, Hungary, and Venezuela.

“And Yet, Liberalism Endures”

Harrison: There are always going to be people challenging liberty and liberalism. There will always be people seeking power. But with enough time, they will be overcome—could you lay out that case?

David: There’s always somebody to scapegoat, whether it’s the Jews or the 1 percent or big business, or the gays or the blacks or whoever, and some form of populism is organized against whichever group of people.

And yet, liberalism endures. We still live in a basically liberal world, at least the United States, Europe, and the rest of what is the liberal world. Something about it seems very resilient.

It allows people to experiment with lots of things, find bad ways of living, and toss them aside. I feel like I’m pessimistic in the short run. We’re going to get a bad president in this next election.

But freedom works and socialism and fascism do not work. Eventually, people will realize that, and to some extent, most Americans do. The longer you project, the more confident I am that we’ll be in a freer world in the future.

Harrison: David, I can’t say enough about the impact you’ve had on me and my career, on the Cato Institute, and on countless people around the world. You’ve done a lot for freedom, and you’ve made the world a freer place. Thank you.