Freedom is a complex idea to advocate for and defend. It demands firm moral standards to treat every individual as a sovereign capable of making decisions and choosing what kind of life they wish to live. It can leave many unsatisfied. Unlike other ideologies, those that value freedom give no special favors to any particular group, making it seem cold or, at times, too rational. But freedom has no favorites. It is the birthright of all.

Classical liberals and libertarians bear the unique burden and circumstances to advocate such a universal ideal that is widely under attack. In such dire circumstances, how do we best defend freedom?

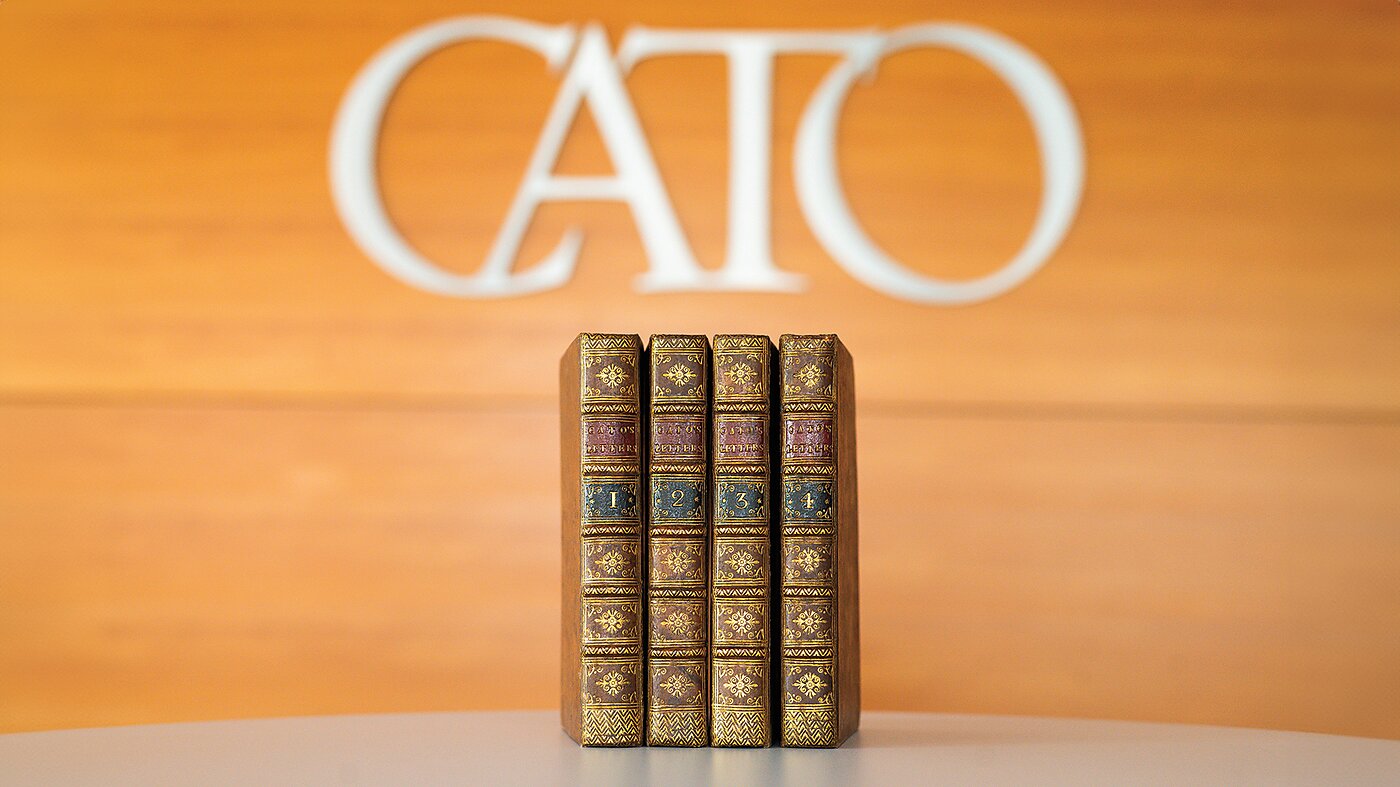

I believe the answer lies in the namesake of the Cato Institute, Cato’s Letters, a collection of essays from 18th-century England written by John Trenchard and Thomas Gordon.

The duo began writing their letters after the South Sea Bubble of 1720. In an 18th-century experiment in crony capitalism, the British state colluded with the South Sea Company to manipulate stock prices for their own gain. When the bubble burst, and the scandal was uncovered, it caused shock and outrage that the highest representatives in government betrayed the public trust in such a conniving manner.

In response, Trenchard and Gordon started writing Cato’s Letters, publishing essays weekly with the London Journal. Trenchard and Gordon did not lament private industry and the market’s influence but instead pinned the blame on the state stepping outside its bounds for the sake of profiteering. They believed it was their duty to advocate bringing the conspirators to justice and to outline the principles of a free society long after the scandal had subsided.

Writing as “Cato,” Trenchard and Gordon synthesized the philosophies of Thomas Hobbes, John Locke, and Niccolo Machiavelli. An odd trio, but in the process, Trenchard and Gordon expounded a novel theory of libertarian civic virtue, the necessary attitudes and habits to maintain a free society.