In 1955 Nobel laureate economist Milton Friedman published “The Role of Government in Education,” in which he made a theoretical case for separating government funding of education from government provision. Rather than operate schools, Friedman argued that the government should grant vouchers directly to parents that they could redeem at the school of their choice.

Let the subsidy be made available to parents regardless [of] where they send their children — provided only that it be to schools that satisfy specified minimum standards — and a wide variety of schools will spring up to meet the demand. Parents could express their views about schools directly, by withdrawing their children from one school and sending them to another, to a much greater extent than is now possible. In general, they can now take this step only by simultaneously changing their place of residence.

- Educational Freedom Wiki Pages

Introduction

- Government Schools, Democracy, and Social Conflict

- Parental Choice and Responsibility

- School Freedom and Competition

- Educational Choice and Accountability

- The Way Forward: Scholarship Tax Credits or Vouchers?

- Personal-Use Education Tax Credits

- Scholarship Tax Credits

In the following decades, Friedman’s school voucher proposal has been debated, critiqued, and even implemented — albeit never quite in the manner Friedman outlined. As of 2014 there are more than 115,000 students participating 23 voucher programs operating in 14 states and Washington, D.C. Though Friedman called for universal vouchers with few regulations, most of the voucher programs are either means-tested or limited to students with special needs — and often the vouchers come with many strings attached, including rigid price controls and state testing mandates.

Another means of expanding educational choice is the scholarship tax credit (STC) law. An STC grants a full or partial tax credit to individual and/or corporate taxpayers in return for contributions to non-profit scholarship organizations. These organizations then help low- and middle-income families enroll their children in the schools of their choice. As of 2014, nearly 200,000 students receive tax-credit scholarships in 13 states.

Both types of choice initiatives have advantages over the status quo, but STC laws have several advantages over voucher programs, including a decreased risk of harmful regulation, more solid constitutional footing, less socially divisive compulsion, and greater popularity.

STCs: Reduced Risk of Regulation

The ideal education system entails an unfettered market in which all students have the financial means to attend the school of their choice. However, government subsidies can open the door to government regulation of private schools, potentially undermining the benefits of parental choice.

In theory, the government can attach regulatory strings to STC laws just as it can vouchers — indeed, the government can regulate private schools even in the absence of either. In practice, however, a detailed statistical analysis reveals that voucher programs impose a large and statistically significant extra regulatory burden on private schools, while STC programs do not. The increased regulatory burden of voucher programs appears in such areas as accreditation, teacher certification, standardized testing, religion, and price controls.

As ever, vigilance is the price of freedom. There are STC programs with substantial regulations, so they are not immune to regulation (nor, for that matter, are private schools generally). Nevertheless, they remain the best way to expand educational choice while minimizing regulations that would undermine parents’ ability to choose.

STCs: A Perfect Constitutional Record to Date

Both vouchers and scholarship tax credits are constitutional under the U.S. Constitution. In 2002, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of Cleveland’s voucher program in a landmark decision, Zelman v. Simmons-Harris. Plaintiffs alleged that the voucher program unconstitutionally funded religious institutions in violation of the First Amendment’s Establishment Clause. However, the majority ruled that voucher programs do not violate the Establishment Clause because they have a secular purpose; they are neutral with respect to religion; the funds are given to parents, not directly to schools; a broad class of students qualify; and there are adequate secular options.

At the state level, however, vouchers have faced more daunting constitutional roadblocks. Most state constitutions contain clauses forbidding the “compelled support” of religious schools or some form of the historically anti-Catholic “Blaine Amendments,” which bar state governments from funding religious education. Although state supreme courts have interpreted these provisions in line with the U.S. Supreme Court’s First Amendment jurisprudence, others have struck down voucher laws under these provisions.

By contrast, STC laws thus far have a perfect constitutional record in the states’ high courts, even in states with Blaine Amendments. Though Arizona’s high court struck down the state’s voucher program, it later upheld its STC law. The key difference is that voucher programs distribute public funds collected from compulsory tax whereas STC laws entail private funding from voluntary contributions. In Kotterman v. Killian, the Arizona Supreme Court ruled:

According to Black’s Law Dictionary, “public money” is “[r]evenue received from federal, state, and local governments from taxes, fees, fines, etc.” […] As respondents note, however, no money ever enters the state’s control as a result of this tax credit. Nothing is deposited in the state treasury or other accounts under the management or possession of governmental agencies or public officials. Thus, under any common understanding of the words, we are not here dealing with “public money.”

Years later, the U.S. Supreme Court held in ACSTO v. Winn that plaintiffs did not even have standing to sue Arizona over its STC law, because the scholarships funds had "not come into the tax collector's hands" and therefore did not constitute public money. Rather, when "taxpayers choose to contribute to [scholarship organizations], they spend their own money, not money the State has collected." In 2014, the New Hampshire Supreme Court likewise ruled that plaintiffs lacked standing to challenge the Granite State's STC law because they could not demonstrate that they were harmed by it. In 2015, citing all the above decisions, the Alabama Supreme Court upheld its state's STC law on the merits, holding that a "tax credit to a parent or a corporation ... cannot be construed as an 'appropriation'." Though states are not bound to follow the decisions of the U.S. Supreme Court or any other state court when interpreting their own state constitution's provisions, the same reasoning should apply.

Freedom of Conscience

Both vouchers and STCs enhance the freedom of conscience of parents by helping parents choose a school that aligns with their values and educational preferences. However, only STCs preserve the freedom of conscience of taxpayers in a manner consistent with America's founding ideals. As Thomas Jefferson wrote in the Act for Establishing Religious Freedom adopted by Virginia in 1786, "to compel a man to furnish contributions of money for the propagation of opinions which he disbelieves... is sinful and tyrannical."

Vouchers do not violate the First Amendment, but like government schools, they compel taxpayers to financially support forms of education to which they may object. Some taxpayers may object to funding religious education, or they may object to funding secular humanist education. Alternatively, a taxpayer may have objections to a school's teaching methods, history curriculum, the use of certain books, and so forth. A voucher program forces all taxpayers to support each family's educational preferences. In the government school system, the majority may force its educational preferences on the minority, or a better-organized minority can even force its will on the majority — a dynamic that has fueled social conflict over schooling for centuries.

By contrast, donations to scholarship organizations under an STC law are voluntary. Taxpayers can choose to donate only to those scholarship organizations that fund students attending schools that align with their values — or they can choose not to donate at all. Some scholarship organizations fund students attending any school of their choice, while others limit their scholarships to students attending schools with a particular educational approach — such as Montessori — or with a particular religious affiliation or lack thereof.

Only scholarship tax credits respect parents' freedom of choice while preserving the taxpayers' freedom of conscience.

STCs Are More Popular

Public policy is not a popularity contest, but a proposal’s political viability depends greatly on the support or opposition it receives from the public. On that metric, STCs have a clear advantage.

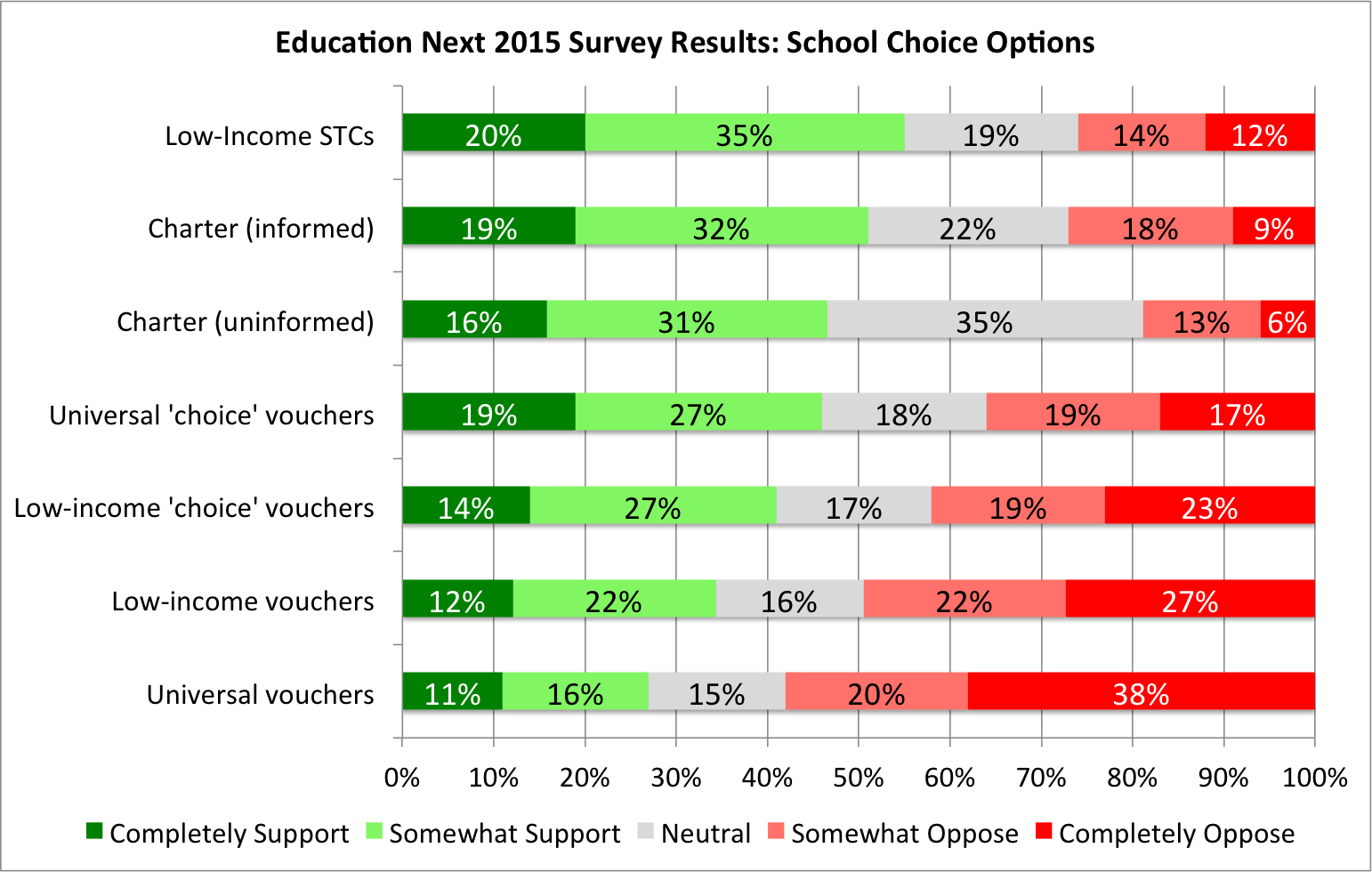

In Education Next's annual survey on education policy, respondents consistently prefer STCs to all other alternatives. In Education Next's 2015 survey, STCs received the support of 55 percent of respondents compared to somewhere between 47 percent and 51 percent for charter schools (depending on whether the survey first explained what charter schools are), 27 percent to 46 percent for universal school vouchers (again, depending on the wording of the question), and 34 percent to 41 percent for low-income vouchers.

Support for STCs was even higher among parents (57 percent), African-Americans (60 percent), and Hispanics (62 percent). This is not surprising since minorities are more likely to be low-income and therefore choice deprived. Those voicing support for STCs more than doubled those opposed in the general public (26 percent) and more than tripled the opposition among African-Americans (16 percent) and Hispanics (18 percent).

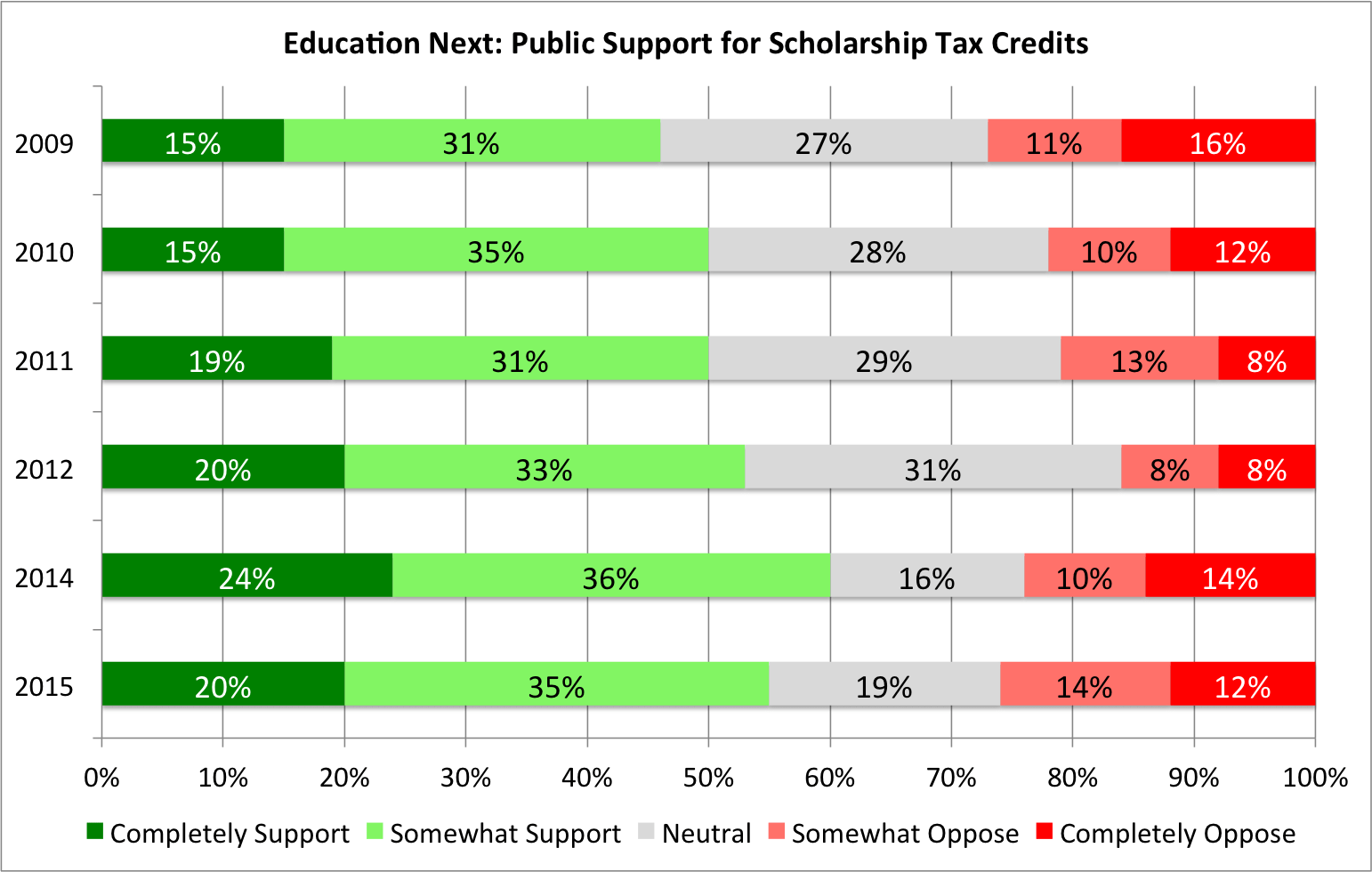

Support for STCs in the Education Next surveys has grown over time, reaching a high of 60 percent in 2014, though it dipped slightly in 2015. Since 2012, STCs have garnered support from a majority of respondents each year. (Education Next did not ask about STCs in 2013.)

By contrast, vouchers only received support from a majority of Education Next respondents in 2014 (51 percent). In other years, the highest level of support among the various ways Education Next phrased the question ranged from 39 percent (2010) to 47 percent (2011) with an average of 43.9 percent support.

A 2014 survey by the Friedman Foundation also found that scholarship tax credits were the most popular form of educational choice. Nearly two-thirds of respondents supported STCs while only one in four were opposed. Support for STCs was even higher among respondents who were parents of school-aged children (67 percent), low-income (67 percent), 35–54 years old (66 percent), 18–34 years old (74 percent), black (72 percent), or Hispanic (80 percent).

By contrast, only 43 percent of respondents supported school vouchers while 21 percent were opposed, when not provided with a definition of "voucher." In a separate question, the survey first explained that a "school voucher system allows parents the option of sending their child to the school of their choice, whether that school is public or private, including both religious and non-religious schools" using "tax dollars currently allocated to a school district." In response to that question, both support and opposition increased, 63 percent to 33 percent, respectively. Low-income, black, and Hispanic respondents were even more favorable with between 72 and 74 percent supporting vouchers.

These surveys do not reveal the factors that account for the difference in support between the programs. Perhaps respondents prefer voluntary private contributions to compulsory tax-funded vouchers. Perhaps some are concerned about the regulations that vouchers often bring, and perhaps others do not want their tax dollars flowing to religious schools. No matter the reason, the political reality is clear: scholarship tax credit laws are the best vehicle to expand educational freedom.

Next up, read about Personal-Use Education Tax Credits.

Additional Resources

Books

- Liberty & Learning: Milton Friedman's Voucher Idea at Fifty edited by Robert C. Enlow and Lenore T. Ealy

Studies

- "Forging Consensus" by Andrew J. Coulson

- "Do Vouchers and Tax Credits Increase Private School Regulation?" by Andrew J. Coulson

- "Measuring Market Education: Suggestions for Ranking School Choice Reforms" by Andrew J. Coulson

- "The Fiscal Impact of a Large-Scale Education Tax Credit Program" by Andrew J. Coulson

- "Live Free and Learn: A Case Study of New Hampshire's Scholarship Tax Credit Program" by Jason Bedrick

Model Legislation

- Scholarship Tax Credits by the Cato Institute Center for Educational Freedom

Amicus Briefs

- Cato Institute amicus brief in ACSTO v. Winn by Andrew J. Coulson and Ilya Shapiro

- Cato Institute amicus brief in Duncan v. New Hampshire by Jason Bedrick and Ilya Shapiro

Commentary

- "Public Schools: Make Them Private" by Milton Friedman

- "The Next Step in School Choice" by Jason Bedrick and Lindsey Burke

- "Tax Credits Better for Schools Than Vouchers" by Andrew J. Coulson

- "The New Hampshire Education Tax Credit Lawsuit Simplified" by Jason Bedrick

- "A ‘Winn' For Education and Freedom of Conscience" by Andrew J. Coulson

- "Design Matters: The Future of School Choice" by Jason Bedrick

- "Low-Income Parents Highly Satisfied with New Hampshire's Scholarship Tax Credits" by Jason Bedrick

- "Expanding Educational Opportunity" by Jason Bedrick and Ken Ardon