According to the White House, the upcoming U.S.-Africa Summit in Washington “will highlight America’s commitment to Africa’s security, its democratic development, and its people.” In just one day, on August 6, 2014, U.S. President Barack Obama will be meeting 50 African leaders to discuss a diverse range of topics including “inclusive, sustainable development, economic growth, and trade and investment,” “peace and security, including a discussion of long-term solutions to regional conflicts, peacekeeping challenges, and combating transnational threats,” and governance, “in order to deliver services to citizens, attract and prepare for increased domestic and foreign direct investment, manage transnational threats, and stem the flow of illicit finance.“1

Without a doubt, it will be a very busy day. However, it should not blind us to the fact that the recent improvements in economic performance and in well-being in sub-Saharan Africa (hereafter Africa) have little to do with symbolic politics and photo ops in Washington. Rather, they are the result of rising commodity prices as well as domestic reforms, such as more prudent fiscal and monetary policies, privatization of state-owned enterprises, and improvements in the business environment. As a 2010 McKinsey report finds, much of Africa's recent growth can be explained by factors such as the reduction of average inflation from 22 percent in the 1990s to 8 percent in 2000s, the reduction of Africa's budget deficits by two-thirds, and by significant improvements in the quality of institutions.2

To sustain and accelerate the current growth of African economies, African leaders need to focus on domestic structural and institutional reforms. They also need to make more tangible progress removing existing barriers to trade and investment on the continent. But African leaders should demand that the West help too, by abandoning its agricultural protectionism, including the wasteful programs of explicit and implicit support of domestic agricultural production, which hurts agricultural sectors in developing economies.

The State of Africa

The last decade was good for Africa. The real gross domestic product rose at an average annual rate of 4.9 percent between 2000 and 2008 — twice as fast as that in the 1990s. Even in the aftermath of the financial crisis, African growth quickly rebounded to rates approaching 5 percent.3 As a result, between 1990 and 2010, the share of Africans living at $1.25 per day or less fell from 56 percent to 48 percent, while the continent's population almost doubled in size. If the current trends continue, Africa's poverty rate will fall to 24 percent by 2030.4 Since 1990 the per-capita caloric intake in Africa increased from 2,150 kcal to 2,430 kcal in 2013.5 Between 1990 and 2012, the proportion of the population of African countries with access to clean drinking water increased from 48 percent to 64 percent.6 Many African countries have also seen dramatic falls in infant and child mortality. Since 2005, some African countries, such as Senegal, Rwanda, Uganda, Ghana, and Kenya, have seen child mortality decline by an annual rate exceeding 6 percent.7

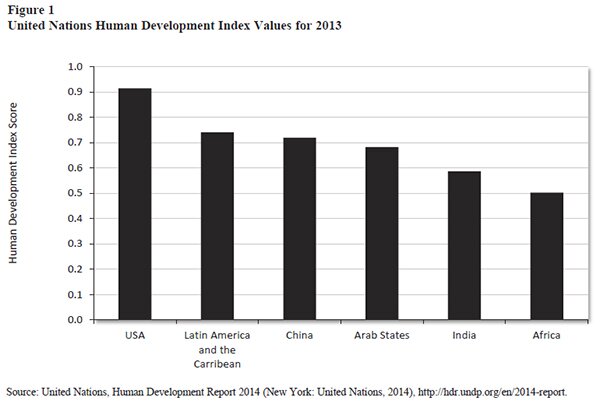

Nonetheless, the continent still lags significantly behind the rest of the world in its income levels and also in many indicators of human well-being. For example, Africa scored a mere 0.502 on the United Nation's 2014 Human Development Index, measured on a scale from 0 to 1, with higher values denoting higher standards of living. By comparison, the United States scored 0.914, Latin America 0.74, and China 0.719 (see Figure 1).

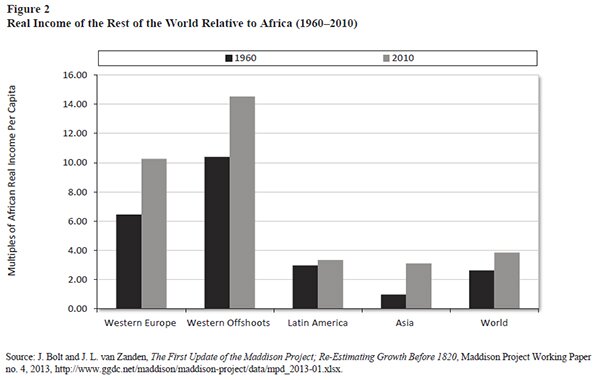

Taking a longer view, the recent economic improvements have not been sufficient to overcome the enormous income gap that has long existed between Africa and other parts of the world. According to the dataset developed originally by the late Angus Maddison, an economist at the University of Groeningen, the income gap between Africa and other regions has grown since 1960 (see Figure 2), although it has declined somewhat after 2000. While Africa has seen tangible progress in recent years, it still is a far cry from the growth miracle that has been unfolding in China and India, or from the ones that brought the countries of Southeast Asia to their current levels of economic development.

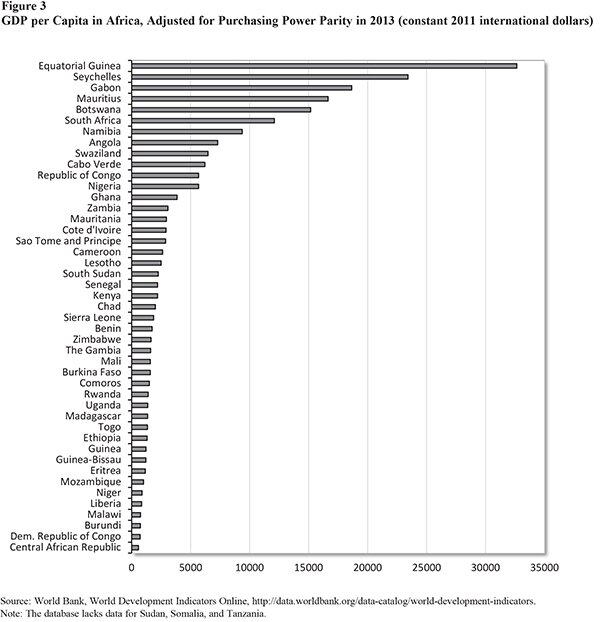

Africa is hardly a homogenous continent. Figure 3 reveals significant differences in income levels across different African economies. The two countries at the top of the list are outliers. The high annual per capita income in Equatorial Guinea, approaching $33,000, is a result of the country's vast oil reserves and does not imply the country is particularly prosperous — in fact, it ranks 144th out of 187 countries evaluated on the 2014 Human Development Index.8 Seychelles, in turn, which enjoys a per capita GDP of over $23,000, has a tiny population of less than 88,000 and a highly developed tourism industry. On the other extreme, per-capita income levels in countries such as Burundi, Democratic Republic of Congo, or in the Central African Republic, still linger well below $1,000.

Aid and Development

The countries of Africa count among the most notable recipients of development assistance, which is still seen by some as important for lifting Africa out of poverty. At the 2005 G8 summit in Gleneagles, UK, world leaders agreed on doubling foreign aid by 2010 and also on canceling the debt of poor countries heavily indebted to the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund, and the African Development Fund. Such policies, which put development assistance ahead of aggressive trade liberalization and the promotion of sound, domestically grown, institutions within Africa, ultimately do a disservice to the continent.

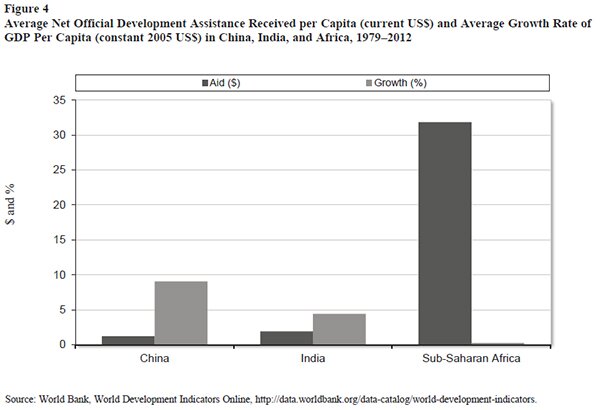

Between 1979 and 2012, average per capita aid flows to Africa came close to $32 per year, compared to $1.93 in India and $1.25 in China. Over the same period, the average annual growth rate in Africa was a mere 0.27 percent, compared to 4.4 percent in India and over 9 percent in China (see Figure 4).

The failure of aid to generate sizeable economic growth in Africa is not just an artifact of the data but is consistent with the findings of a number of influential studies in development economics, which have concluded that aid does little to foster economic prosperity.9 Today, the size and the scope of global capital markets make Africa's access to capital potentially easier than at any time in the past, significantly weakening the case for aid. Indeed, private capital flows to developing countries now dwarf aid flows. Remittances from high-wage countries to developing countries alone total around $400 billion — or four times global aid flows; the size of foreign direct investment is roughly similar.10

Trade Barriers in Africa

Countries that improve their policies and institutions — by increasing their trade openness, limiting state intervention in the economy, building a business-friendly environment, and emphasizing protection of property rights and the rule of law — tend to grow faster than others.11 Such countries are also better at attracting foreign capital, which helps to increase economic growth. Credible improvements in policies and institutions increase confidence and foster investment and economic growth.

Alas, Africa remains the least economically free region in the world.12 The extent of trade protectionism, for example, is large, especially when compared with other regions in the world. Average applied tariffs in Africa remain comparatively high, and the extent of trade liberalization on the continent has not matched that experienced in the rest of the world. While between 1988 and 2010, the average applied tariff in high-income countries in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development fell from 9.5 percent to 2.8 percent, Africa saw a reduction from 26.6 percent to 11 percent. That is not a negligible decrease but it still leaves the continent with unnecessarily high tariff protection, which hinders trade.13 It is not altogether surprising that Africa's trade still accounts for only a small fraction of global trade flows. In 2012, for example, Africa's total merchandise exports constituted only 3.3 percent of the world's exports — less than in the 1970s.14

Tariffs facing African exporters within Africa are often higher than those facing African exporters in other parts of the world. For 13 African countries, bilateral tariff costs for agricultural products are higher vis-à-vis their regional trading partners in Africa than with the rest of the world. For manufactured goods, tariff costs within Africa are higher than with the rest of the world in the case of 25 African countries.15

In addition to tariffs, a plethora of nontariff barriers to trade exists in African countries, ranging from bad infrastructure, sanitary and phytosanitary rules, to corruption. A recent study by the Rwandan Ministry of Trade and Industry reveals that in order to reach the port in Mombasa, Kenya, a little over 1,000 miles from Kigali, a truck driver must stop at 26 different road blocks and navigate eight weight bridges. At 11 of the roadblocks and at seven of the weight bridges, officials request bribes, totaling an average of $846, not to mention that the journey used for the study took more than 121 hours.16 And, as a World Bank economist noted in 2012, "in southern Africa, a truck serving supermarkets across a border may need to carry up to 1600 documents as a result of permits and licenses and other requirements."17

It is then not a surprise that intraregional trade — trade among African countries — accounted for only 11 percent of the region's total trade in 2010,18 which is significantly lower than in other developing regions — not to speak about advanced economies. Intra-EU trade, for example, accounted for almost 64 percent of total trade in the EU in 2010.19 If African governments were interested in expanding trade, liberalization within the region would surely be a desirable goal, especially as it does not depend on the West's policy decisions.

What Africa Needs

The most significant bottlenecks to Africa's economic development are internal to Africa and will have to be addressed by Africans. These include

- Rule of law. Without a functioning court system, local and foreign investors cannot do business effectively, especially on a large scale.

- Poor governance, inefficient bureaucracies, and corruption. African governments often lack accountability and instead advance the objectives of the political elites.20

- Red tape. The World Bank's Doing Business reports show that improvements in the regulatory environment result in greater private sector investment and higher economic growth.21

- Infrastructure. While investment in infrastructure is costly and will take many years to complete, privatization of inefficient government monopolies, such as ports and railways, can be done relatively easily.

- Regional economic integration. Trade within Africa is significantly smaller as a percentage of African exports than is the case in other parts of the world. Unfortunately, regional free-trade initiatives, such as the African Free Trade Zone, have not yet resulted in a significant reduction of trade barriers within Africa. For most African countries, unilateral trade liberalization can be a feasible and appealing alternative to protracted trade negotiations.

- This is not to say that developed nations, such as the United States, cannot help Africa grow. In particular, the elimination of the existing barriers to trade should be at the forefront of the efforts to help. Such barriers include tariffs, particularly on agricultural exports, which make it difficult for African economies to fully exploit their comparative advantage. As Brookings Institution researchers Emmanuel Asmah and Brandon Routman note, the structure of the tariff protection in the United States — but also in the European Union — is a significant part of the problem. The tariffs imposed up to a certain amount of imports may be low, yet the tariffs imposed for imports above the permitted quota might be very steep, in some cases up to 350 percent.22 Furthermore, agricultural subsidies in rich countries cause surplus production, which is often dumped on the world markets, depressing prices and undermining the livelihood of farmers in poor countries.23

However, African problems cannot be solved in Western capitals, and the region need not rely on the West to develop. Persistent poverty in Africa is caused primarily by flawed domestic policies and institutions. As such, it can be overcome only by changes made by Africans themselves. African governments must ultimately embrace the reforms that have made other regions of the world prosper.

Notes

This paper is based, in part, on Marian L. Tupy, The False Promise of Gleneagles: Misguided Priorities at the Heart of the New Push for African Development, Cato Institute Development Policy Analysis, April 24, 2009.

1 The White House, U.S.-Africa Leaders Summit, 2014, http://www.whitehouse.gov/us-africa-leaders-summit.

2 Acha Leke et al., "What's Driving Africa's Growth," McKinsey Quarterly, June 2010, http://www.mckinsey.com/insights/africa/driving_african_growth.

3 Marian L. Tupy, "Capitalism Will Eliminate Poverty in Africa," Brenthurst Briefing, April 20, 2012, https://www.cato.org/publications/commentary/capitalism-will-eliminate-….

4 Laurence Chandy, Natasha Ledlie and Veronika Penciakova, Africa's Challenge to End Extreme Poverty by 2030: Too Slow or Too Far Behind? Brookings Institution, May 29, 2013, http://www.brookings.edu/blogs/up-front/posts/2013/05/29-africa-challen….

5 Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Food Security Indicators, 2014, http://www.fao.org/economic/ess/ess-fs/ess-fadata/en.

6 United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF), Water and Sanitation Coverage data, http://www.data.unicef.org/water-sanitation/water.

7 Gabriel Demombynes, Ritva Reinikka, "Africa's Success Story: Infant Mortality Down," Africa Can (blog), World Bank, May 7, 2012, http://blogs.worldbank.org/africacan/africas-success-story-infant-morta….

8 United Nations, Human Development Report 2014 (New York: United Nations, 2014), http://hdr.undp.org/en/2014-report.

9 See, e.g., Peter Boone, "Politics and the Effectiveness of Foreign Aid," NBER Working Paper no. 5308 (1995), http://www.nber.org/papers/w5308, or William Easterly, Ross Levine and David Roodman, Aid, Policies, and Growth: Comment, "American Economic Review 94, no. 3 (2004): 774–80. Harold Brumm of the United States General Accountability Office concluded that foreign aid retards growth even in countries that follow sensible policies. Harold J. Brumm, "Aid, Policies, and Growth: Bauer Was Right," Cato Journal 23, no. 2 (Fall 2003). Similarly, in a comprehensive review of foreign aid, Raghuram Rajan and Arvind Subramanian of the International Monetary Fund found "no evidence that aid works better in better policy [environments]." Raghuram G. Rajan and Arvind Subramanian, "Aid and Growth: What Does the Cross-Country Evidence Really Show?" Review of Economics and Statistics 90, no. 4 (2008): 643–65.

10 Paul Collier, Exodus: How Migration Is Changing Our World (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013), p. 160.

11 James Gwartney and Robert Lawson, Economic Freedom of the World: 2008 Annual Report (Vancouver, BC: Fraser Institute, 2008), p. 18.

12 Many African countries lack functioning legal systems that protect private property. Africa also remains one of the least integrated regions in the global economy and its private sector is hobbled by some of the most restrictive business regulations in the world. See James Gwartney, Robert Lawson, Joshua Hall, Economic Freedom of the World: 2013 Annual Report (Vancouver, BC: Fraser Institute, 2013).

13 Data for average MFN applied tariff rates in developing and industrial countries, 1981–2010 (unweighted in %) from World Bank, Trends in Average MFN Applied Tariff Rates in Developing and Industrial Countries, 1981–2010, http://siteresources.world bank.org/INTRES/Resources/469232-1107449512766/tar2010.xls.

14 United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (UNECA), Overview of Recent Economic and Social Developments in Africa (Addis Ababa: UNECA, 2014), http://www.uneca.org/sites/default/files/uploaded-documents/COM/com2014…, p. 7.

15 UNECA, Trade Facilitation from an African Perspective (Addis Ababa: UNECA, 2013), http://www.uneca.org/sites/default/files/publications/trade_facilitatio…

16 Ministry of Trade and Industry, Experiential Survey on Non Tariff Barriers Along the Northern Corridor (Kigali, Rwanda: Ministry of Trade and Industry, 2013), http://nmcrwanda.org/IMG/pdf/ntbs_east_africa_rising_final.pdf.

17 Paul Brenton, "De-Fragmenting Africa," VoxEU (March 17, 2012), http://www.voxeu.org/article/de-fragmenting-africa.

18 Simon Mevel and Stephen Karingi, Deepening Regional Integration in Africa: A Computable General Equilibrium Assessment of the Establishment of a Continental Free Trade Area followed by a Continental Customs Union, Paper for Presentation at the 7th African Economic Conference, Kigali, Rwanda, October 30–November 2, 2012, http://www.afdb.org/fileadmin/uploads/afdb/Documents/Knowledge/Deepenin….

19 Franca Faes-Cannito, Gilberto Gambini, and Radoslav Istatkov, "Intra EU Share of EU-27 Trade in Goods, Services and Foreign Direct Investments Remains More than 50% in 2010," Eurostat Statistics in Focus 3/2012 (Luxembourg: Eurostat, 2012), http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/cache/ITY_OFFPUB/KS-SF-12-003/EN/KS-SF….

20 See Moeletsi Mbeki, "Underdevelopment in Sub-Saharan Africa: The Role of the Private Sector and Political Elites," Cato Institute Foreign Policy Briefing Paper no. 85, April 15, 2005.

21 See, for example, World Bank, Doing Business 2008.

22 Emmanuel Asmah and Brandon Routman, Removing Barriers to Improve the Competitiveness of Africa's Agriculture (Washington: Brookings Institution, 2011), http://www.brookings.edu/~/media/research/files/reports/2011/6/01%20imp….

23 According to Thomas Beierle of Resources for the Future, overproduction in the developed world depresses world commodity prices by 12 percent. Developed countries are also responsible for 80 percent of the global price distortions in agricultural commodities. Thomas C. Beierle, From Uruguay to Doha: Agricultural Trade Negotiations at the World Trade Organization (Washington: Resources for the Future, March 2002), p. 9, http://www.rff.org/Documents/RFF-DP-02-13.pdf.