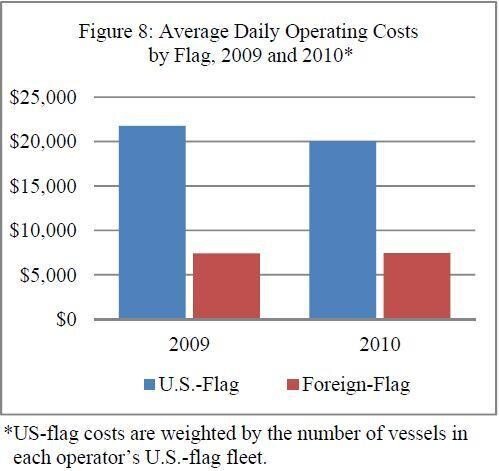

While it is certainly not the only factor at play, this precipitous decline in the U.S. fleet’s standing is due in no small part to burdensome regulations which make American ships more costly and less competitive. The Jones Act requires ships engaged in the U.S. trade to be built in the country, but building a ship in the United States is exorbitantly expensive—three times the cost of a new ship built in Japan or South Korea. In nearly all cases it is far less burdensome to purchase an existing ship and reflag it rather than build new. And these burdens are before factoring the requirement to crew these ships with U.S. mariners, union men who unsurprisingly average more than five times the expense of a foreign crew. Indeed, the MARAD report identified labor costs as the single largest driver of the difference between U.S. and foreign carrier costs.

The Jones Act isn’t the only harmful regulation, not by a mile. One of the unfortunate realities of operating a massive ocean-going vessel full of complex machinery is that things inevitably require maintenance. These inconveniences often arise overseas and necessitate repairs in foreign countries. Lest you worry the government would be left with beak unwetted in this instance, fear not: 19 USC § 1466 to the rescue (link included if you’re having trouble falling asleep). This outgrowth of the Tariff Act of 1930 requires the master, or owner of a vessel, upon the ship’s return to a United States port, to declare to U.S. Customs any parts and services received onboard while in foreign waters. The ship owner is then required to pay an ad valorem duty of 50 percenton the dutiable vessel repair costs.

A few exceptions written into the law help mitigate this figure, at the further cost of man hours or maritime attorney fees. Free trade agreements between the United States and nations like Oman, South Korea, Singapore, and others help to alleviate these costs by allowing for almost total remission of duty for work performed in those countries. However, it’s hardly practical for U.S.-flagged vessels to perform the entirety of their maintenance in these countries when stays in port can be measured in hours. Vessel repair duties are situated to remain a significant, punitive cost of doing business as a U.S. cargo vessel. Even with this 50 percent duty, in the majority of cases it is still less expensive to make the repairs overseas and pay up rather than to perform the work in the United States. This also holds true for the acquisition of new ships.

Thus, under the Jones Act, shipping prices (as well as those for the goods shipped) riseand the U.S. fleet degrades. (For more on how the Jones Act imperils U.S. maritime security, see this helpful Heritage Foundation report.) It’s quite the double-whammy, and precisely what you’d expect from a protectionist law that thwarts the benefits of foreign competition. In short, the Jones Act has turned the U.S. merchant marine into a fleet of Ford Pintos and Chrysler K‑Cars, all in desperate need of the kind of motivation only free market competition can bring.

To Top It Off, the Jones Act Worsens Emergencies

Moreover, the Act has proven to be a significant and costly obstacle in times of real emergency. Most recently, the deep freeze of 2014 saw New Jersey exhaust its supply of road salt, imperiling the lives of local travelers. Such salt was available in Maine, but it was delayed for days because of the requirement that only U.S. ships could engage in coastwise trade to carry the shipment—even though an empty foreign ship was available and headed to Newark. The government denied a request to waive the Jones Act and use the foreign ship to supply the much-needed road salt. By the time a Jones Act barge was found to carry the salt, the cost of the operation had grown by $700,000. Sorry about those icy roads, New Jersey, but the shipping industry and unions gotta get paid.

During the Deepwater Horizon oil spill, the governmentsimilarly refused to issue Jones Act waivers so foreign vessels could aid in the cleanup and containment. Despite several offers for foreign assistance during an ongoing ecological disaster, the government cited the Jones Act to justify turning them away. Many suspect that the Obama administration was reluctant to go against the pro-Jones Act labor unions (tr. every labor union) he needed to cement his re-election. It’s not a leap to say that such cronyism may have delayed the eventual resolution of the spill.

The Jones Act and its related statutes raise the cost of essential goods for American families and businesses; strangle the life from the industries they were designed to protect; jeopardize U.S. maritime security; and exacerbate the pain of major national emergencies. (They also are major irritant in foreign trade relations.) So why hasn’t Congress repealed these laws? Maybe we should ask the politicians and well-connected cronies who benefit from the current arrangement. I’m sure they’d be happy to explain.

McCain’s amendment to repeal the Jones Act is a common-sense solution to the problems facing a key American industry and the pain of the U.S. economy. The amendment, as well as any broader proposal to kill off the Act, deserves widespread support from conservatives and liberals alike. Efforts to dispense with this archaic protectionist boondoggle will no doubt meet fierce resistance from entrenched interests, labor unions, and opponents of free trade. However, those same groups stand only to benefit from efforts to make the U.S. fleet more competitive and less costly. American mariners have what it takes to compete on a global scale, and they should be given the chance. More competition translates to more opportunity, and perhaps the expansion and revitalization of a crucial sector of our economy. Where artificial monopolies and ancient restrictions can be removed, American labor, American business, and American consumers will have a chance to thrive.