I would be the first to argue that if an economist claims to know of a cure-all policy — a reliable way to relieve a long list of social ills in one fell swoop — common sense tells you to stop listening.

So it is awkward for me to declare that I know of something close to a panacea policy: one big reform that would raise living standards, reduce wealth inequality, increase productivity, raise social mobility, help struggling men without college degrees, clean the planet and raise birth rates. It’s a sweeping reform that Democrats and Republicans, progressives and conservatives could all proudly support.

The panacea policy I have in mind is housing deregulation. Research confirms that there are large benefits in saying yes to tall buildings, yes to multifamily structures, yes to dense single-family development and yes to speedy permitting. The growing YIMBY (Yes In My Backyard) movement already has high-profile wins in Minnesota, Oregon, California and beyond, but even YIMBY devotees rarely appreciate the scope of the merits of loosening rules on housing.

Supply and Demand

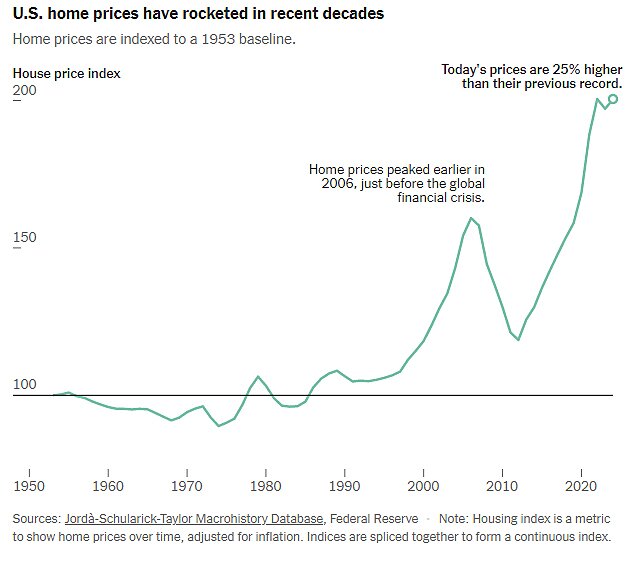

The case for housing deregulation starts with Econ 101: Allowing builders to significantly increase housing supply leads to much lower prices. This is hardly wishful thinking. Before the rise of stricter regulation in the 1970s, the textbook model worked well: When demand pushed prices above the cost of production, more construction drove prices back down. We have decent U.S. data since the 1950s, and until recent decades, there was no long-term upward trend in prices. Now, despite a downtick during the Great Recession, the upward march is unmistakable: Today’s inflation-adjusted (and quality-adjusted!) housing prices are now far above their previous peaks.

How do researchers know that excessive regulation is causing high housing prices? Using the process of elimination. It isn’t rising demand, as the U.S. population rose even faster back when housing prices were roughly stable. It isn’t because of higher construction costs — those, adjusted for inflation, have been almost flat for decades.

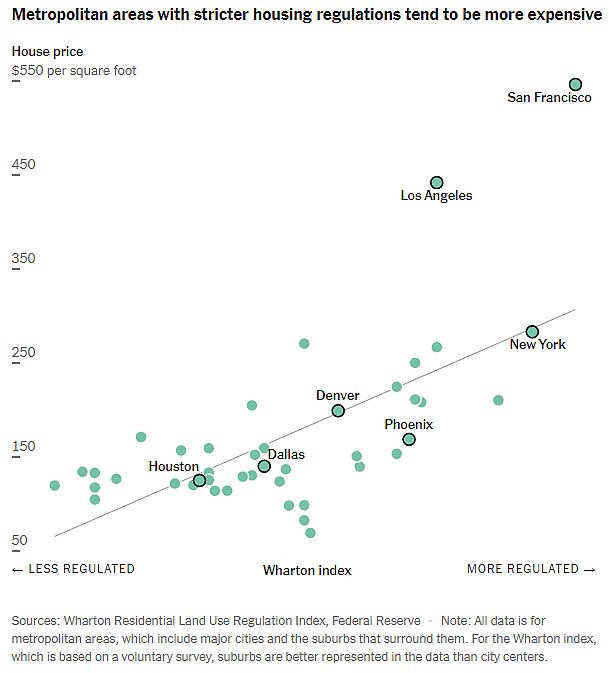

On the other hand, there is good evidence that heavy-handed housing regulation is boosting home prices by restricting supply. Strictly regulated urban areas like New York City and the Bay Area have high prices and low construction, while more lightly regulated areas like Houston and Dallas have much lower prices and much more construction.

Standard of Living

What would happen if homebuilders could once again freely build until housing prices were driven back down to cost? According to a conservative estimate, prices would ultimately fall about 50 percent on average nationally — with significant, wide-ranging implications. The most direct would be a sharp jump in the average American’s economic well-being. Since shelter is now roughly 20 percent of the average American’s budget, halving its price makes the cost of living 10 percent lower — and the standard of living 11 percent higher. This would be welcome news for those struggling to make rent or buy a first home. And while current homeowners would see their house values drop, those who sold to developers could still make a killing.

Wealth Inequality

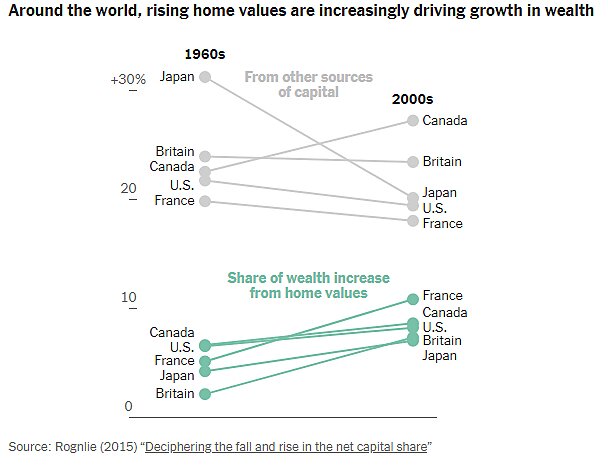

The distributional effects would be almost as striking. Ten years ago, the economist Thomas Piketty’s book “Capital in the Twenty-First Century” reignited international debate on growing wealth inequality and argued for progressive wealth taxes to counter the trend. What few laypeople have heard, however, is that the economist Matthew Rognlie almost immediately followed up with evidence that it is the rising value of homes that primarily accounts for the increasing disparity between the rich and the poor.

As house prices have risen in major metropolitan areas where the wealthy tend to own property, their wealth has grown faster than that of homeowners in less affluent areas and even faster than that of the poor, who spend a larger share of their income (25 percent) on housing and are much more likely to rent. This is true not just in the United States but also in Japan, France, Britain and Canada. Freeing up construction would, therefore, enrich and equalize at the same time.

Social Mobility

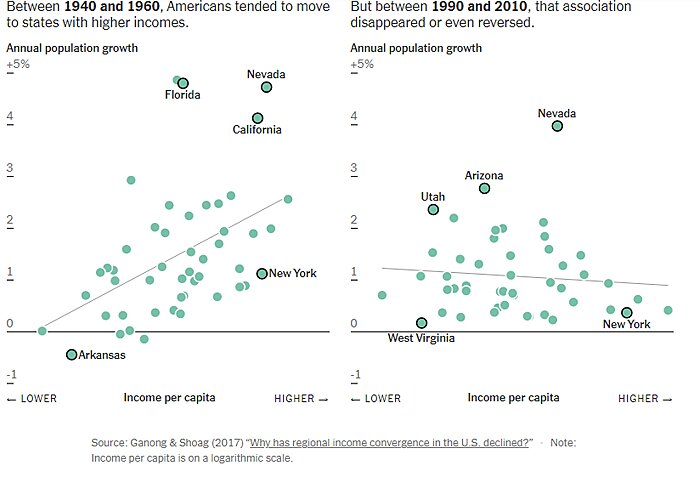

Inequality aside, many long for an economy with greater social mobility. What few appreciate is that the overregulation of housing has blocked a classic American path: moving to a higher-wage part of the country to secure a better life. A paper by the economists Peter Ganong and Daniel Shoag shows that housing costs now routinely outweigh wage gains: While janitors and waiters do indeed earn higher salaries in the Bay Area, they have to spend much more than their extra pay on rent. Programmers and lawyers who move to gold-rush regions still come out ahead, but the rest of the workforce is gradually getting out of Dodge. In a functional society, self-interest inspires workers to relocate to wherever they are most productive. In our society, strict housing regulation has decoupled movement and value, leading to the mass migration of lower-income residents away from geographic centers of technological progress and economic growth.

Struggling Men

Housing deregulation would be especially advantageous for one of America’s most downwardly mobile demographics: men without college degrees. Anne Case and Nobel Prize recipient Angus Deaton famously called attention to non-college males’ poorer job prospects and “deaths of despair.” But over 80 percent of construction workers have not graduated from college, and almost 90 percent are male. Construction is already a large sector, employing about 10 million workers at an average wage over $37 per hour, well above the average for full-time non-college males. Allowing even mild deregulation would therefore create millions of promising career paths — and well-paid ones at that — with full-throated deregulation adding millions more, all without requiring disaffected young men to learn to code.

Carbon Emissions

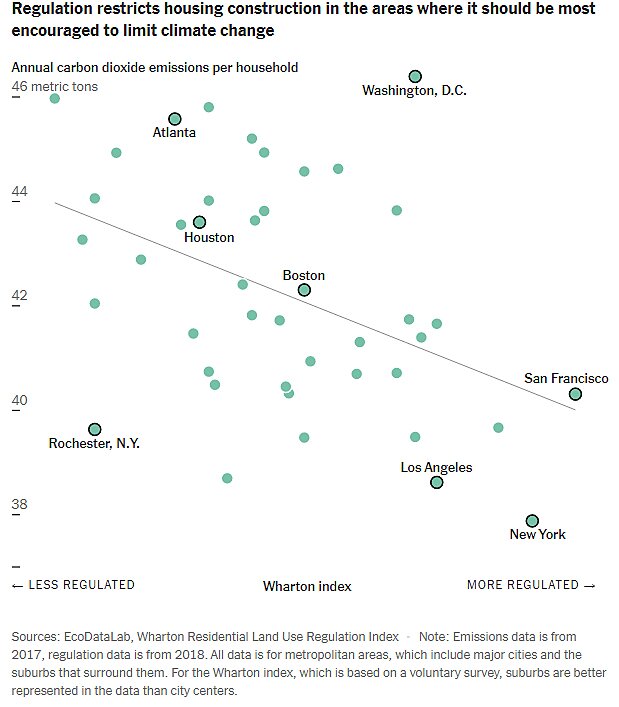

Environmental protection is one of the top rationales for restricting construction. But deregulation can allow more housing to be built in areas with naturally lower carbon emissions. Central cities are almost always greener than their surrounding suburbs; smaller homes at higher densities, plus less driving, tends to shrink environmental footprints. Temperate regions like California perversely have the strictest housing regulations, which redirects the country’s population to areas with greater heating and cooling needs and higher emissions.

Fertility

If American birth rates keep falling, the problem of low housing supply will ultimately take care of itself. But if we wish to avoid the many dangers of a society-wide population crash, deregulating housing as soon as possible could be part of a far-sighted response. Culture matters, too, but high housing costs often keep young adults living with their parents for many extra years, delaying both marriage and childbearing. The admittedly small number of studies on the link between YIMBY and babies support common sense: Less regulation lowers housing prices, and lower housing prices generally raise birth rates and hasten child-bearing.

Even sympathizers often believe that housing deregulation will never happen. They blame self-interested voting, arguing that because most Americans own homes, they will stonewall any policy to make homes cheaper.

But the naysayers’ confidence is misplaced. As a general rule, ideas, not self-interest, drive voting. Compared with Republicans, Democrats have long supported higher taxes on the rich and higher benefits for the poor. But rich Democrats and poor Republicans still abound. A national survey found that along with 42 percent of homeowners, 35 percent of renters favored a full-blown ban on new construction in their neighborhoods. This is unsurprising in light of other research finding that most Americans, whether owners or renters, don’t think that extra housing supply means lower prices. About 35 percent believe increased supply raises prices; another 25 percent believe no change in price would occur. The big barrier to deregulation is not homeowners’ selfishness but denial of Econ 101.

Neither Democrats nor Republicans have embraced housing deregulation yet. YIMBY activists lean left, but they are only one voice in the progressive coalition. Republican states usually have less housing regulation, but more from tradition than from principle. Yet, given housing deregulation’s many demonstrated benefits, this policy agenda deserves bipartisan support. Democrats should cheer the effects on equality, social mobility and the environment. Republicans should be delighted to see free markets spreading broad prosperity, creating new working-class opportunities and fostering family formation. In a rational world, the panacea policy of housing deregulation would be a done deal. Hopefully whoever wins the next election will agree.