Dear Capitolisters,

One of this newsletter’s persistent themes is that we should generally be skeptical of easy policy solutions because a lot of policy is—like the real world—difficult, complicated, and replete with real trade-offs. There are many examples of this reality throughout history, but a new one relates to whether and how to regulate artificial intelligence. On the one hand, some industry experts and technologists familiar with the speed of AI development and the technology’s potential—especially in the wrong hands—have concerns about what it might become without some sort of government oversight. The risk of Skynet or whatever, so they say, may be low, but since it’s an existential risk it merits regulation. On the other side, and certainly where my sympathies lie, are other technologists, many (most?) economists, and people familiar with the long history of hysterical technophobia and innovation-stifling regulation who warn against heavy-handed government intervention in this space. Overall, these debaters are smart, well-intentioned people discussing a tough issue, and reasonable people can disagree based on legitimate evidence and argument provided.

Judging from the headlines and various politicians’ statements, however, the most talked-about reason to regulate AI—because industry leaders themselves demand it—could very well be the worst.

The Long, LONG History of Incumbents Demanding They Be Regulated

Concerns over AI’s economic and existential risks are not exactly new, but they’ve certainly increased since Microsoft-backed OpenAI released the fourth version of its AI chatbot, ChatGPT, this March. Shortly thereafter, for example, bajillionaire Elon Musk joined several AI experts and industry executives to pen an open letter calling on all AI labs to take a six-month pause in developing systems more powerful than GPT‑4, citing AI’s “profound risks to society and humanity.” The concern hit a fever pitch last week when OpenAI CEO Sam Altman told the Senate Subcommittee for Privacy, Technology and the Law that he supports wide-reaching AI regulation (e.g., licensing by a new government or international agency).

Altman’s testimony prompted many in the hearing room and elsewhere to allege that it was clear and convincing evidence new regulation was needed. Leading the charge was Senate Judiciary Chair Richard J. Durbin, who called the testimony “historic” and added:

I can’t recall when we’ve had people representing large corporations or private sector entities come before us and plead with us to regulate them. … In fact, many people in the Senate have based their careers on the opposite, that the economy will thrive if government gets the hell out of the way.

The senator may wish to have his memory checked.

Indeed, history is littered with examples of large incumbent firms begging to be regulated not for the public interest but for their own. As Jonah noted in an old(ish) G‑File, for example, Facebook’s hamfisted efforts to encourage new tech regulation had ample historical precedent:

At the end of the 19th century, the railroad magnates successfully petitioned the federal government to protect them from “cutthroat competition” and the hassles of rate wars. We have the Interstate Commerce Commission thanks to those allegedly rapacious free market capitalists and “robber barons.”

I could regale you with similar stories about everything from the steel and meat packing industries in the Progressive Era to movie chains during the New Deal.

Even Upton Sinclair—author of The Jungle—eventually admitted that the regulation he helped bring about benefited Big Meat. “The Federal inspection of meat was, historically, established at the packers’ request,” Sinclair wrote in 1906. “It is maintained and paid for by the people of the United States for the benefit of the packers.”

Over at the Washington Examiner, Tim Carney—long the scourge of corporatists everywhere—provides a top-of-head laundry list of other examples: Insurance companies (and, separately, insurance agents), hedge funds, tax preparers, credit card companies, investment banks, Uber, Philip Morris, lightbulb companies, and—again—Facebook all have supported stricter regulation of their own industries to pad their own bottom lines, not out of some benevolent concern for the common good (whatever that even means). Tim’s 2006 article in the Cato Policy Report adds Enron (lol), General Motors, and U.S. Steel to the pile, along with more history on the longstanding bromance between Big Business and Big Government.

Elsewhere, AEI’s Bronwyn Howell finds a direct historical parallel between Altman’s reasoning and previous please-regulate-me incumbents:

Early telephone providers sought regulatory protection from competition and pharmaceutical providers sought additional government registration of their products before public use. These calls were couched in terms of ensuring that any new products and services proffered in the market met the same known quality and safety standards already demonstrated by the original providers. (“We can be trusted, but what about the newcomers?”) Nonetheless, the ensuing regulations had the effect of preserving an incumbent advantage for the original providers—that is, creating a barrier to entry for newcomers.

Allow me to provide a few more examples from just the last few years:

- In 2018, Amazon lobbied for a higher minimum wage to hurt Walmart and other competitors. Shortly thereafter, Walmart did much the same.

- That same year, AT&T urged Congress to pass an “Internet Bill of Rights”—a move dubbed “just a power play against Google and Facebook.”

- In 2018, Exxon Mobil opposed the Trump administration’s rollback of U.S. methane regulations that “hurt small producers the most.”

- Executives at Alphabet, Microsoft, Meta, and Apple went to Davos in 2020 and begged for a wide array of new tech regulations.

- In 2021, shipping giant Maersk called for a $150/ton carbon tax on shipping fuel, but “Maersk’s scale would enable the company to weather such a hike in what constitutes the industry’s single largest expense.”

- Big banks and smaller brick-and-mortar banks have recently called for more regulation of their upstart fintech competition.

I could go on, but you surely get the idea: The only thing “historic” about an industry leader asking for more regulation is that the asks occur often throughout U.S. history.

Why Incumbents Favor Regulation

Surely, not every regulation is embraced by large businesses, but there are obvious reasons why many are. Indeed, regardless of one’s views of a specific regulation or regulation more broadly, it’s hardly controversial to acknowledge that government economic rules can favor large, incumbent organizations (also known as “big business”) over new market entrants and thus act as an innovation-crippling “moat” between the latter and market viability. As George Mason University’s Tyler Cowen noted in a recent column, some of this is just common sense: Big firms “have more employees, bigger legal departments and are better suited to deal with governments,” whereas startups typically lack those resources. Thus, “as regulatory costs rise, the comparative advantage shifts to the larger firms” who can more easily handle the new costs.

I experienced this dynamic a lot in my decades as a practicing lawyer at a big U.S. firm. Trade policy in the United States is primarily a regulatory process administered by the Commerce Department and other U.S. agencies, and trade cases can quickly get costly and complicated. A single U.S. anti-dumping investigation, for example, can last more than a year and rack up hundreds of thousands of dollars (if not more) in legal fees for companies (foreign exporters or U.S. importers) caught up in them. Large companies, whether based here or abroad, have in-house counsel/accountants or deep pockets for outside counsel, and can therefore navigate these byzantine cases more easily. As a result (and often working with affiliated foreign exporters), these big companies can win for themselves lower, company-specific duties, while their smaller competition is stuck with a higher, “all others” duty rate that makes their products more expensive (and thus makes them less competitive versus the big guys). It was relatively common to watch small foreign exporters or small U.S. importers (who are on the hook for future duties) simply drop out of a particular market at the mere initiation of a new administrative action because fighting back would cost a ton and maybe (probably) be futile anyway.

(Yes, this was depressing to watch.)

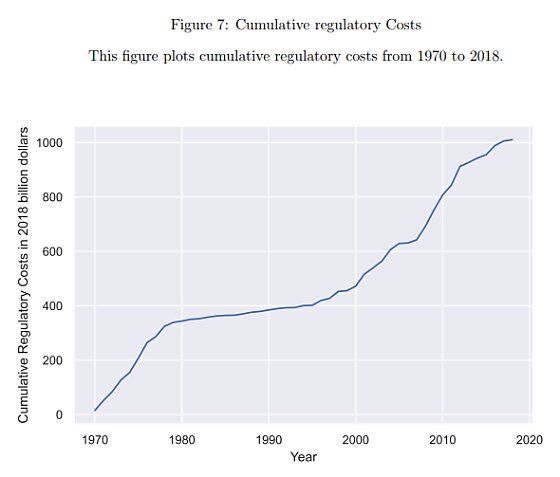

It’s no surprise, then, that academic literature also finds a link between big regulation and big business. Cowen notes, for example, a new study showing how increased regulation contributes to more concentrated markets. In particular, economist Shikhar Singla found that between 1970 and 2018 U.S. regulatory costs increased by $1 trillion (5 percent of 2018 U.S. GDP) …

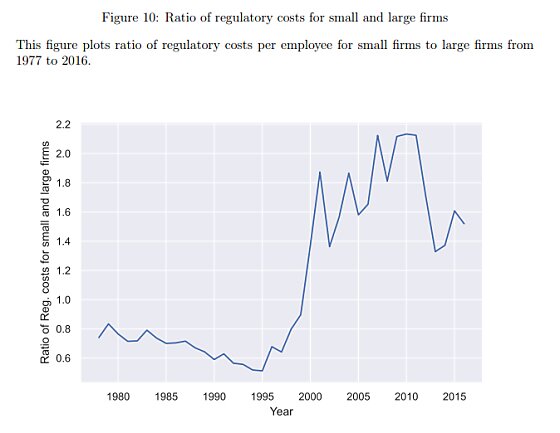

… and that, starting in the late 1990s, this cumulative regulatory burden was disproportionately borne by smaller businesses: “An average small firm faces an average [burden] of $9,093 per employee in our sample period compared to $5,246 for a large firm.”

As a result, big companies experienced increased sales, employment, markups, and profitability during the period examined, while smaller ones experienced just the opposite: “The smaller the firm, the more competitively disadvantaged it gets, and vice-versa.” Various markets also saw fewer entrants, lower productivity, and less investment by the late 1990s and thereafter—right as smaller firms started taking a higher regulatory hit than their larger competitors. Overall, he finds that “increased regulations can explain 31–37% of the rise in market power” among large U.S. companies during the last few decades. Singla also documents the political side of rulemaking: “While large firms are opposed to regulations in general, they push for the passage of regulations that have an adverse impact on small firms. … Hence, they are willing to incur a cost that creates a competitive advantage for them.”

Someone tell Sen. Durbin!

Anyway, previous studies have come to similar conclusions on the chilling effects of regulation on market entry and innovation, often finding big business lobbying behind the scenes. Bailey and Thomas, for example, found in 2017 that “more-regulated industries experienced fewer new firm births” between 1998 and 2011, and that “large firms may even successfully lobby government officials to increase regulations to raise their smaller rivals’ costs.”Calomiris and colleagues in 2020 found that higher regulatory exposure generally harms firms’ financial performance, but that “these effects are mitigated for larger firms.” And Calcagno and Sobel (2014) calculated that regulation “appears to operate as a fixed cost” that favors larger firms over smaller ones. This, again, is common sense: If all companies pay around the same price for regulatory compliance, the companies that make more money will suffer relatively less.

Summing It All Up

There are, I think, plenty of reasons to be skeptical of new AI regulation. For example, various technologists have pushed back on the idea that the technology, even in much advanced form, will have the power and potential to pose an existential risk to humanity. (Many have rightly noted, moreover, that current technology really isn’t “AI” at all.) And, yes, malicious actors may abuse the technology, but there are obvious and non-obvious ways that others can work to counter such baddies—including via the same technology (sorta like how your spam filter battles spambots). For those interested, Adam Thierer of the R Street Institute has a great, frequently updated primer on much of this discourse.

Meanwhile, the potential benefits of the actual ChatGPT and similar technologies—not their demonic potential selves—could be seismic in a wide range of fields. As economist Tim Taylor recently detailed, for example, the early research on AI shows tremendous upside for the productivity of workers—especially less-skilled ones—and economic growth. (He also noted, as I did a few months ago, just how hysterical and overambitious past predictions of tech-related doom have been.) AEI’s Brent Orrell notes similar benefits, and the technology is already revolutionizing medicine in various ways (e.g., cancer detection). Regulation could—consistent with past research—stifle these gains, and past attempts to regulate scary stuff (e.g., nuclear weapons) haven’t fared very well.

Thierer adds, moreover, that the U.S. tech sector owes its world-beating status to a “permissionless innovation” approach that other nations, particularly in Europe, have eschewed to their detriment. And he’s right to note that countries like China aren’t going to slow down their AI efforts just because we have. Other observers, such as former FTC official and current “innovation evangelist” Neil Chilson, have pointed out that the same people who wanted a new “digital regulator” two or three years ago are doing the same dance today for AI—even with the same legislation. (Same goes for Section 230 and content moderation.) Sure looks like they’re just groping for problems that can justify pre-existing government solutions.

People are free to disagree, and—as already noted—it’s a complicated issue with reasonable counterarguments to some of the points above. As Eli Dourado notes, moreover, Sam Altman’s financial stake in OpenAI may mean he’s sincere in his views about the need for AI regulation (though he can still be wrong and can still have other, non-financial motivations for stifling his competition). But that doesn’t mean it’s no less wrongheaded—and it certainly doesn’t justify new federal law. Let that be decided on the merits, not some absurd conception of big business and “history.”

Charts of the Week

Huh.

average pitch velocity pic.twitter.com/A3WUpZakP1

— Jay Cuda (@JayCuda) May 21, 2023