Dear Capitolisters,

Practicing law at a large firm for an extended period—17 years in my case before I fully embraced wonkery—does weird things to your brain. You tend to think, speak, and argue in enumerated-list format (something annoyed spouses know all too well). You get antsy when someone doesn’t return your texts or emails within 5 minutes (at most) or when you can’t respond instantly in-kind. You become incredibly adept at breezing through airport security and develop unreasonable expectations about office coffee. But perhaps the most brain-altering thing about practicing in “Big Law” is that recording your entire professional life in detailed, six-minute increments—and getting compensated on that basis—makes you acutely, obsessively aware of time and its value.

Unlike the other disorders, however, this last one is an objectively good thing.

(Well, most of the time.)

I thought of this a couple weeks ago during my regular Costco run when I noticed the literal traffic jam in the parking lot, caused by antsy shoppers waiting in long lines—each at least 15 cars deep—for the company’s famously cheap gas.

We’ve officially reached the pt at which the lost time sitting in the crazy Costco gas line (15–20 min) is > the savings (.20/gal) said gas provides.

— Scott Lincicome (@scottlincicome) March 12, 2022

My decision to forgo the line and pay a little more for gas across the street made for an easy joke on Twitter (as things do), but it also hit on an economic principle—“opportunity cost”—that gets little attention in Washington yet should inform our thinking on not only personal line-waiting protocols but also public policy.

Seriously, Don’t Wait in Line

My colleague Ryan Bourne’s great book, Economics in One Virus, defines “opportunity cost” as “the value of the best alternative forgone as a result of a purchase or a decision,” and the Costco gas line provides a great example of how the principle works in our daily lives. There, I’d have to spend an extra 20 to 30 minutes in line to save about $3 bucks ($0.20/gallon times 15 gallons) versus the no line options across the street. Quickly doing that math—and no doubt extra motivated by the sighing 9‑year old in my backseat—I realized that it made far more sense for me to pay $3 than to waste dozens of precious weekend minutes to save it.

How we each value our time, of course, can be pretty subjective, but there are some general rules of thumb. Most obviously, there’s the value of your working time as determined by the market—essentially your total work compensation (wages, benefits, etc.) expressed in an hourly rate. You can run your own numbers yourself, but the latest data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics provide a useful benchmark: Total employee compensation averaged $40.35/hour in December 2021. Applying that standard to my example, we see that 20 to 30 minutes would be—to the average worker—worth a lot more than 3 bucks.

Since this wasn’t in the middle of my workday, however, we must also consider the value of non-working time, which raises trickier issues:

In the past, at least, it’s not been very easy to turn spare time into money, so time outside one’s normal job is basically given a value of zero. But this clearly isn’t true. If it were, you’d accept a second job at one dollar an hour. After all, all you’re giving up is leisure — time to relax, to interact with your family, to exercise, to volunteer. Since most of us wouldn’t take that deal, we must value free time more.

How much we value it is a complicated function of our income, how much we like our work or dislike it, what other priorities we have in our lives, and how much we’re currently working for pay. Someone who’s working very little may not value an extra hour of leisure very much. Someone who’s working a lot of hours would value it a lot — and hence might be willing to pay extra to get her dry cleaning delivered so she has time to go for a run.

The reason why this matters is that having a rough dollar value in mind helps you make smarter choices. If you value your leisure time at $30 an hour, then driving 15 minutes out of your way to save a few bucks on your dry-cleaning probably isn’t worth it.

As Wikipedia explains in the context of transit policy, economists and social scientists have developed two main ways to determine how much people actually value their free time: “Since this time is not valued in a market, it can only be estimated from revealed preference or stated preference analysis techniques, where the real or hypothetical choices of travelers between faster, more expensive modes and slower, cheaper modes can be examined. For example, if a traveler has a choice between a coach which takes six hours and costs £10, or a train which takes four hours and costs £30, we can deduce that if the traveler chooses the train, their value of time is £10 per hour or more (because they are willing to spend at least £20 to save two hours’ travel time).”

Various studies have employed these techniques to derive a basic benchmark hourly rate for our non-work time. One study, for example, asked survey respondents in 2014 to provide the minimum amount of money they’d be willing to accept (or the maximum they were willing to pay) for trading 1 hour of paid work per week for 1 hour of unpaid work (e.g., household chores) or 1 hour of leisure time. The answer: about 16 euros (or $25.50/hour in 2022 dollars). A brand new study, meanwhile, used detailed GPS data on American drivers’ driving routes, gasoline refueling stops, and nearby station prices to document refueling patterns and determine how far off their normal routes drivers would be willing to drive to save money on gasoline (and thus how much drivers valued their time over cost savings). The result: “the median gas stop occurs within less than a one minute deviation from a driver’s shortest route, despite the possibility of saving an average of $0.09 per gallon within a two minute deviation.” Thus, drivers valued their travel time—“their observed willingness to travel further from their routes in order to pay a lower expected gasoline price”—at about $27.54/hour.

Both of these figures strike me as way too low, and research does indeed show that people tend to seriously underestimate the value of their time because they don’t fully grok opportunity costs:

Systematic under-weighting of opportunity costs… leads individuals to work for one hour (analogous to selling time) for [their hourly wage rate] or more even though they are only willing to pay less than [their hourly wage rate] in cash to spare the expenditure of their own effort (analogous to buying time). Underappreciation of opportunity costs leads to people being temporal spendthrifts and monetary misers, wasting time on lower value activities at the expense of higher value pursuits.

Regardless, applying these (too low!) non-work benchmarks still shows that—unless there are no other options nearby (e.g., the annoying coffee line at the airport)—it makes little sense to wait more than a few minutes in line to get gas or, really, most things in life (groceries, coffee, etc.).

Next time, just walk/drive away.

It’s Not Just Gas Lines

Once you get time-pilled about opportunity costs, you see them almost everywhere—and not just when standing in line for gas or groceries. Bourne notes, for example, that opportunity costs are a core part of:

-

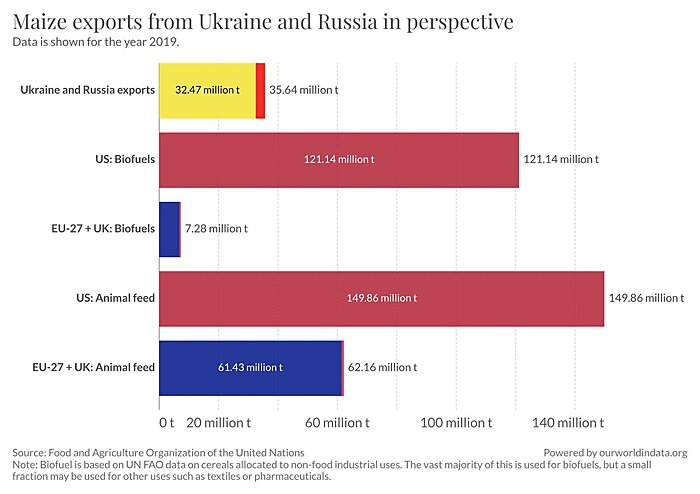

Trade policy. “Comparative advantage” teaches us that individuals and countries are worse off when they try to make everything themselves (instead making some things and freely trading for the rest), because their finite time and resources (capital and labor) could have been deployed instead on work they’re better at performing. We also discussed this principle last week regarding petroleum products trade and “energy independence.”

-

Pandemic policy. Onerous restrictions on business and individual activity may save lives, but—given their immense costs (e.g., lockdowns “inhibit our ability to do anything else”)—the same resources might have been deployed in a more effective way to save or improve lives at a societal level.

-

Transportation policy: “We could nearly eliminate road deaths by capping motor vehicle speeds at 5 miles per hour. But the lost time and business activity resulting from that regulation would be tremendous, making people poorer and leading to hardship and worse health outcomes.”

Opportunity costs are also a big driver of post-pandemic remote work. In particular, recent studies have shown that working from home during the pandemic saved Americans tens of millions of hours commuting—hours that they spent instead on work, leisure, chores, and other valuable things. That time—averaging about an hour per day before the pandemic (which translates to 10 days per year and almost a year of your entire work life)—plus additional expenses like gas or transit fares is essentially your daily commute’s opportunity cost. And remote work lets us deploy resources once spent (wasted!) on commuting in more productive ways, resulting in broader economic benefits in the long run (see study here).

As I explained in a paper last year, U.S. industrial policies also impose opportunity costs that proponents rarely consider:

Given that both time and federal budgets are finite, government industrial policies replace efforts and money that could have been spent on other priorities, potentially imposing significant opportunity costs in the process. In The Technology Pork Barrel, for example, [the authors] explain that the Clinch River breeder reactor “absorbed so much of the R&D budget for nuclear technology that it probably retarded overall technological progress.” Other nuclear projects, and the Space Shuttle, likely had similar net negative effects. As noted above, more recent government overspending on Emergent BioSolutions’ pricey anthrax vaccines left less money available to purchase other medical goods, such as N95 masks, for the Strategic National Stockpile, thus contributing to its shortages when COVID-19 arrived in 2020.

And just this week, we’re getting another lesson in opportunity costs: Taxpayer funds that were spent on the overstuffed American Rescue Plan could have instead been used on the treatments, tests, or fourth vaccine doses that the Biden administration now claims lack sufficient federal appropriations. (You were warned!)

Indeed, once you accept that public and private resources are finite—and unless you’re maybe a Bible character or MMT economist, you do!—opportunity costs are everywhere.

Even at the gas station.

Chart(s) of The Week

Speaking of opportunity costs:

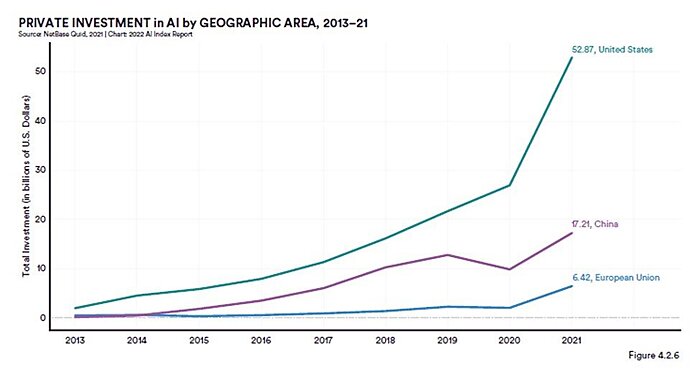

The USA dominates private investment in AI (link):

The Links

Gabby Beaumont-Smith and I talk nail tariffs and U.S. construction costs

EIG report on economic dynamism, sclerotic regulation, and the American worker

Related: Ohio, globalization, and adjustment

“What Operation Warp Speed Did, Didn’t and Can’t Do”

Anti-automation longshoremen unions lament US ports’ “need for better labor efficiency”

It appears that China’s population has peaked

Markets scare Xi into action (or, at least, into pretending to act)

Maryland’s Larry Hogan strikes a needed blow against credentialism

California’s environmental quality act is a disaster

Import substitution fails again

American shoppers rebel against price increases

USA remains the most charitable country

Wildcatters (and the profit motive) to the rescue?

Supply side reforms are the key to fighting stagflation

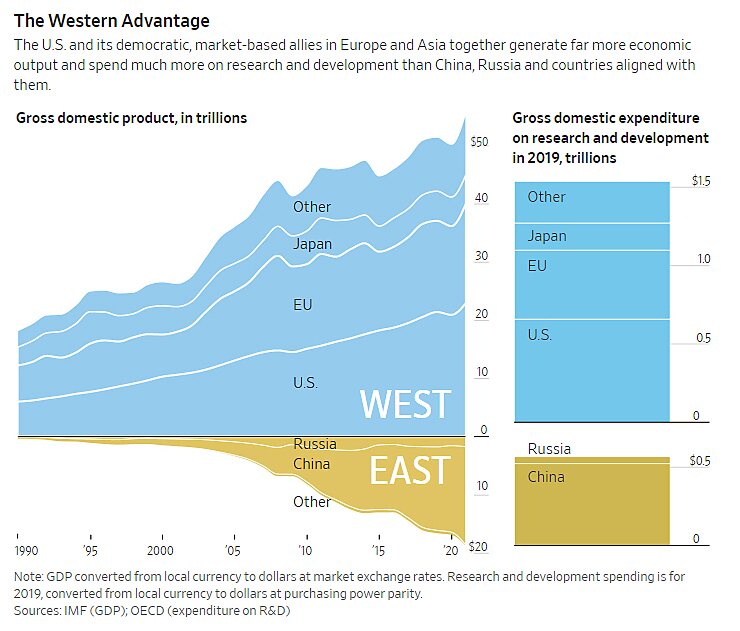

Liberalism is the West’s economic and geopolitical advantage

The Senate accidentally voted to make DST permanent (but “instituting permanent standard time is optimal for almost all cities”) (more)