The tweet below from The Atlantic’s Derek Thompson kicked off an interesting debate on X/Twitter: why is childcare so expensive?

First, let’s establish whether the premise is correct. Looking across states, childcare costs actually vary dramatically. The average cost of full-time infant center care in 2020 ranged from a low of $5,933 in Mississippi to a high of $24,378 here in Washington DC (data from Childcare Aware of America); for family home-based care the equivalent figures ranged from $4,309 to $18,425 for those same places.

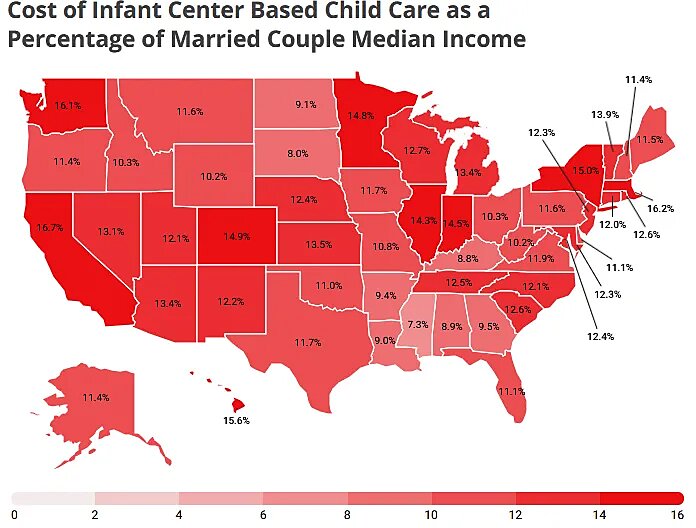

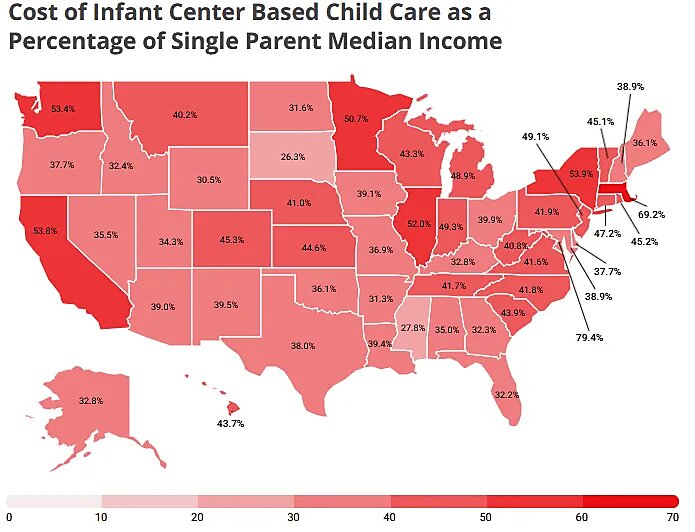

As a share of family’s incomes within states, however, these costs are relatively large across the board. The chart below shows, for example, that the average cost of full-time infant center care for one child exceeds 7 percent of median married couple family income across all states. That’s the threshold that childcare campaigners derive from the federal government (erroneously) as a litmus test of affordability. The five most affordable states are Mississippi, South Dakota, Kentucky, Alabama, and Louisiana. The five least affordable states are California, Massachusetts, Washington, Hawaii, and New York.

Since single parents have lower incomes, these prices as a percentage of state-level median single parent income are, perhaps unsurprisingly, much higher still. We’re talking well over 25 percent in all states, above 50 percent in five states, and 79.4 percent here in Washington DC. Those are obviously prohibitive for many single parents to afford formal center-based care.

Market-Based Reasons for Expensive Care

There are good reasons why we’d expect childcare to be expensive in a high income country that is growing.

First: Baumol’s Cost Disease. For obvious reasons, childcare is a labor-intensive industry, which is difficult to automate. A person sitting and feeding a baby is a person sitting and feeding a baby. You can’t yet substitute a person for a machine to change a diaper, shepherd a child around a playground, or put a kid down for a nap. In the economics jargon, humans are non-substitutable and achieving productivity gains (doing more with less) in childcare is difficult. Wages are typically at least 60–85 percent of childcare center expenses.

As productivity grows across other parts of the economy, raising wages elsewhere, then working in childcare becomes less attractive. Since parents still demand childcare services (not least because their own opportunity cost of being a stay-at-home parent becomes higher as wages rise), childcare centers must compete on wages with those industries, despite carers’ productivity remaining stagnant.

The result is that, although childcare wages still tend to be low in level terms (in a free-market, lots of people have the requisite base-level skills to become childcarers), childcarers’ wages tend to rise over time with the rest of the economy. Rising costs and flatlining productivity is a recipe for childcare becoming more and more expensive relative to other goods and services, so taking up a greater share of people’s rising incomes. Hence, the “cost disease.”

Now, precisely because the Baumol cost disease effect operates through increasing productivity raising wages in other sectors, most of the population would still be able to strictly afford childcare even if prices rise. But parents tend to recoil over time at how childcare costs are eating up a bigger and bigger share of their rising incomes. Many other families just cannot justify the outlay given their preferences.

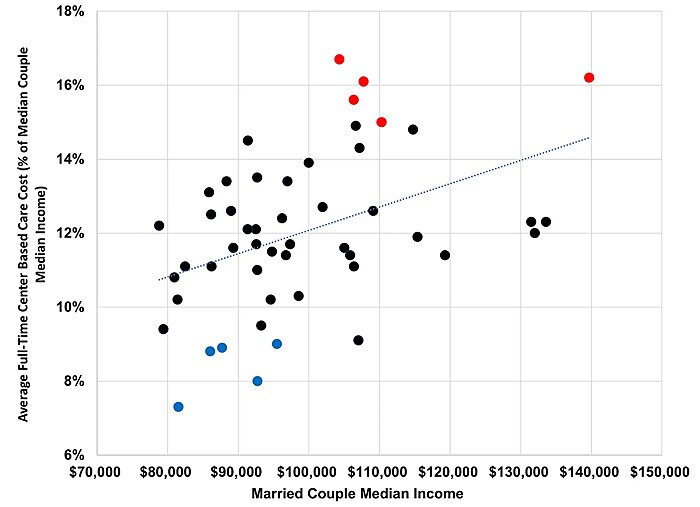

One prediction of this effect is that childcare will be disproportionately more expensive in high income areas. Listing states by median income levels doesn’t perfectly correlate with a state’s unaffordability (r = 0.4), but, as you can see, there is a modest correlation between the two (the five least affordable states are in red; the five most affordable in blue).

Second: binding safety constraints. As noted above, one way to keep the costs of any industry down is to have workers do more! Yet in childcare, it’s not just that it’s difficult to automate, but there’s obviously a limit to how many children any one carer can safely look after.

Let’s leave aside formal regulation for a second: given parents care a lot about the welfare of their children, even in a free-market they will still tend to seek out providers who they believe will be safe and attentive to their children’s physical and mental wellbeing. That means their kid getting sufficient interaction and oversight.

This effectively caps the number of children that most parents will tolerate any given childcarer tending to. Those constraints, though, create a ceiling-like effect on the marginal revenue product of each childcare worker, partly explaining why childcare workers’ wages tend to be low (limited revenue potential per worker).

It also explains why setting an affordability expectation that says nobody should have to pay more than 7 percent of their income on childcare is daft. There’s no feasible world where everyone who wants childcare could pay this little of their household income for formal care in a market.

Take infant care. Imagine a world where we had a bunch of dual-income parent families where both parents earned median income. If childcare prices were such that each family only had to spend, say, 5 percent of their combined household income on full-time childcare, then for a childcare worker to earn even 40 percent of the two-parent household income (80 percent of median), they’d have to care for at least 8 children at once. In fact, it would be substantially more than that, given expenses such as center rent, toys and activities, cleaning services and a profit margin.

Except for the irresponsible or desperate, no parents would allow a young infant to be cared for alongside more than 7 other children at the same time. So, in reality, childcare prices have to be much higher than this to make childcare viable as a service that people desire.

Third: changing tastes. In theory, the sheer scale of the potential supply of childcare in a lightly regulated market should provide options that keep prices down. In an ideal world, we’d see an incredibly pluralistic sector, where not only do you have formal centers and home-based childcarers, but lots of nannies, au pairs, babysitters, after-school shared parental arrangements, kid shares between several households, creches within workplaces, family members being paid to care for kids and more. Such a market would help serve families with varying needs.

There’s lots of evidence to suggest, however, that as people get richer, they generally tend to demand more in the way of higher quality services. For childcare, this means rising incomes generate lots of demand for formal care with bells and whistles, including strong educational components.

Precisely because such “high-quality care” is associated with intensive interaction (high staff: child ratios), carers with qualifications in child development, and top-of-the-range facilities, it tends to be higher marginal cost to produce. As such, it is more expensive. If a critical mass of people demand such care in an area, it can make other providers uneconomic, due to insufficient demand. Part of the reason that childcare is getting more expensive is therefore because, as we get richer, we want a more expansive type of service.

Now, developments like this are just part of the workings of a market economy. So long as there’s relatively free entry for other options to serve different customers, then these outcomes are fine. Unfortunately, in lots of local markets, politicians and regulators, no doubt encouraged by the tastes of the relatively affluent, have imposed these preferences through the force of regulation. When that happens, cheaper, informal, and flexible childcare options are effectively banned.

Non-Market Reasons for (More) Expensive Care

So, to recap: we should expect childcare to be relatively expensive. It’s a highly labor-intensive industry, that’s difficult to automate, and one in which parents put a high value on there being both a safe environment and (increasingly) an intensive learning environment for their child.

Yet it’s certainly true that government regulations raise costs higher than they need be in many places, not least by constraining the supply capacity of the sector. The most significant have been introduced in the name of improving the quality of care. But, ultimately, parents should be the judge of quality: a lot of these regulations raise prices and eliminate informal options, which leads to families not being able to afford care and so turning to worse providers or missing job opportunities that can harm the children’s living standards in other ways.

I wrote about these formation regulations extensively in a recent Cato publication.

Tight staff‐child ratio requirements, when they go beyond what any parent would otherwise demand, raise the net cost of providing childcare by reducing workers’ revenue-earning potential. This reduction either lowers wages for childcare providers, discouraging them from entering the sector, or makes it more expensive and complicated for some centers to operate at a given capacity, leading to fewer centers or home‐based settings. This raises market prices.

Empirical research confirms that unnecessarily stringent staff‐to‐child ratios in some states substantially increase prices with little beneficial effect on observed childcare quality. Thomas and Gorry estimated that loosening staff‐child ratios by just one child across all age groups (regulations vary by child age) reduced center‐based care prices by 9–20 percent. Earlier research suggested that increasing the number of children that any care provider could look after by two would cut prices by 12 percent.

Tight staff-child regulations are highly regressive. Using an extensive dataset across three census periods, Hotz and Xiao found that tightening the staff‐child ratio by one child reduces the number of childcare centers in the average market by 9–11 percent without increasing employment at other centers. Crucially, this supply reduction occurs wholly in lower‐income areas, making it more difficult for poor families to juggle childcare and work responsibilities. States in some places could relax these requirements, producing fairly big savings for parents.

Occupational licensing requirements, such as educational qualifications and training requirements for caregivers, also raise childcare prices by restricting the pool of potential childcare providers. Thomas and Gorry found that requiring lead providers to have even a high school diploma can increase prices by 25–46 percent. Hotz and Xiao likewise found that increasing the required years of education of center directors by one year reduces the number of childcare centers in the average market by 3.2–3.6 percent.

These regulations vary widely by state but can be very stringent. In California, personnel in childcare centers must have at least 12 postsecondary semester credits in early childhood education and development and six months of experience working in a licensed center with children of the relevant age. Center directors must have four years of relevant experience in a center or, alternatively, a degree in child development with two years’ experience. In Washington, DC, recent restrictions are even wilder: center directors must have a bachelor’s degree in early childhood education, ordinary childcare providers in centers are required to have an associate’s degree in early childhood education, and assistant teachers and home childcare providers need at least a Child Development Associate (CDA) credential by December 2023.

These types of credentialist regulations thus enshrine into law the tastes of wealthier childcare consumers for specialist staff. In doing so, they raise prices substantially by constraining the supply of carers, harming poorer consumers in particular.

Restrictive federal immigration policies. The supply of childcare workers, and alternatives, such as au pairs and babysitters, is further curbed by lengthy foreign labor certification processes, low visa caps, and limited visa availability for nannies living outside the home of care. Cortes (2008) found, for example, that for every 10 percent increase in low‐skilled immigrants among the labor force, prices for “immigrant‐intensive services,” including childcare, fell by 2 percent.

Zoning restrictions. Many state and local governments have considered home daycares a “problem use” and have therefore used zoning restrictions to ban them. Such restrictions reduce the availability of childcare in the affected neighborhoods and further increase the price of childcare services.

Associated other rules. There are many other small regulations across states and countries that seek to professionalize the sector, including on property requirements, training, and inspection regimes that deter entry too. Perhaps more egregiously, a lot of places make it illegal to exchange money for services so that groups of parents, extended family members, and other help can be utilized to create childcare arrangements more befitting families’ needs.

Government Subsidies Don’t Reduce Childcare Costs

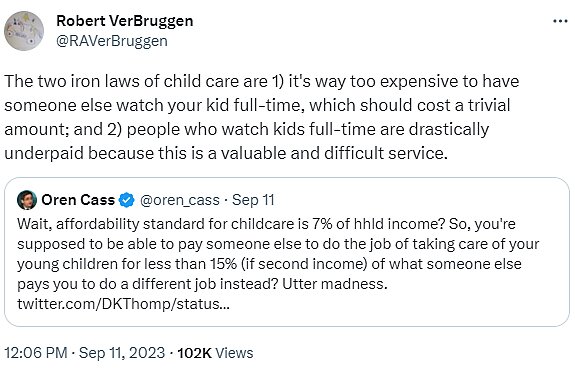

So, childcare costs and market prices would be reasonably high anyway. Then government comes along and pushes the costs of providing childcare higher still through regulations. Hence, we reach the dilemma posed by the original tweet. Progressives seem to think both that childcare should be much cheaper and that childcare workers are massively underpaid. To them, the way to alleviate both is simple: massively subsidize the sector.

In this discussion, a lot of confusion stems from how we talk about childcare prices and costs. In a market, the price of childcare is obviously largely determined by the cost of supplying childcare. Subsidies, by and large, do not affect the cost of supplying childcare and so cannot reduce the “cost of childcare” or its underlying market price. What they do is change who pays (taxpayers instead of consumers), reducing the out-of-pocket price that parents face.

Joe Biden’s “Build Back Better” plan for childcare would have thrown out huge subsidies under a means-tested copayment system to ensure that nobody paid more than 7 percent of their income on childcare. There were all sorts of quirky problems with this policy. But the important point is that those subsidies would have actually been accompanied by requirements that childcare workers were paid similarly to equivalent workers in elementary schools — which would mean pay rises of at least 22 percent.

Added to a host of other regulations on quality that the Democrats wanted to bundle in, the legislation would have raised the underlying cost of providing childcare, rather than making it cheaper to provide. Taxpayers would have been picking up a large part of a much larger bill than parents face today.

The additional, longer-term problem is that subsidizing Baumol’s cost disease like this could make childcare even more expensive in time. By guaranteeing providers’ income and making consumers less sensitive to price, government subsidies would surely worsen the incentive to innovate and control costs in future, leading to waste and bloat.

What justifies such extensive subsidies in the childcare market anyway? That something is expensive doesn’t mean there’s any market failure. If your income is not enough to pay someone to take care of your kid, then it may just be more efficient for society that you care for your own child (or if you don’t like that option, then you only have children when you can afford formal care). To justify the subsidies, campaigners for this largesse therefore dream up “market failure” explanations for why government should get involved anyway.

As I’ve written before, these tend to be unconvincing. Perhaps the strongest case is that intensive childcare at a young age can significantly improve deprived children’s life-chances. Yet this clearly doesn’t require such expansive subsidies so high up the income scale; at best, it points to means-tested support to some families. Indeed, there’s evidence to suggest universal (or near-universal) childcare programs can be very harmful.

Others use economically confused arguments, like the idea that subsidizing childcare is required to help “getting more mothers into the labor force to boost the economy and government budget.” But if a market failure doesn’t exist, we should care about efficiency, not the public finances. Indeed, the role of the state is not to maximize everyone’s formal labor force participation or contributions to the Treasury.

The big picture then is that we’d expect, absent the invention of kid-caring robots, that childcare would get relatively more expensive in a free market as incomes grow. And that’s ok. Yet there are undoubtedly pro-market regulatory reforms on the margin that could be undertaken to lower costs and so market prices. This would be a more productive use of political attention than just shunting the bill for ever-more expensive care to taxpayers.